Analog SFF, April 2010 by Dell Magazine Authors

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Where Are the Distant Worlds? Star Maps

W here Are the Distant Worlds? Star Maps Abo ut the Activity Whe re are the distant worlds in the night sky? Use a star map to find constellations and to identify stars with extrasolar planets. (Northern Hemisphere only, naked eye) Topics Covered • How to find Constellations • Where we have found planets around other stars Participants Adults, teens, families with children 8 years and up If a school/youth group, 10 years and older 1 to 4 participants per map Materials Needed Location and Timing • Current month's Star Map for the Use this activity at a star party on a public (included) dark, clear night. Timing depends only • At least one set Planetary on how long you want to observe. Postcards with Key (included) • A small (red) flashlight • (Optional) Print list of Visible Stars with Planets (included) Included in This Packet Page Detailed Activity Description 2 Helpful Hints 4 Background Information 5 Planetary Postcards 7 Key Planetary Postcards 9 Star Maps 20 Visible Stars With Planets 33 © 2008 Astronomical Society of the Pacific www.astrosociety.org Copies for educational purposes are permitted. Additional astronomy activities can be found here: http://nightsky.jpl.nasa.gov Detailed Activity Description Leader’s Role Participants’ Roles (Anticipated) Introduction: To Ask: Who has heard that scientists have found planets around stars other than our own Sun? How many of these stars might you think have been found? Anyone ever see a star that has planets around it? (our own Sun, some may know of other stars) We can’t see the planets around other stars, but we can see the star. -

On the Detection of Exoplanets Via Radial Velocity Doppler Spectroscopy

The Downtown Review Volume 1 Issue 1 Article 6 January 2015 On the Detection of Exoplanets via Radial Velocity Doppler Spectroscopy Joseph P. Glaser Cleveland State University Follow this and additional works at: https://engagedscholarship.csuohio.edu/tdr Part of the Astrophysics and Astronomy Commons How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! Recommended Citation Glaser, Joseph P.. "On the Detection of Exoplanets via Radial Velocity Doppler Spectroscopy." The Downtown Review. Vol. 1. Iss. 1 (2015) . Available at: https://engagedscholarship.csuohio.edu/tdr/vol1/iss1/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Scholarship at EngagedScholarship@CSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Downtown Review by an authorized editor of EngagedScholarship@CSU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Glaser: Detection of Exoplanets 1 Introduction to Exoplanets For centuries, some of humanity’s greatest minds have pondered over the possibility of other worlds orbiting the uncountable number of stars that exist in the visible universe. The seeds for eventual scientific speculation on the possibility of these "exoplanets" began with the works of a 16th century philosopher, Giordano Bruno. In his modernly celebrated work, On the Infinite Universe & Worlds, Bruno states: "This space we declare to be infinite (...) In it are an infinity of worlds of the same kind as our own." By the time of the European Scientific Revolution, Isaac Newton grew fond of the idea and wrote in his Principia: "If the fixed stars are the centers of similar systems [when compared to the solar system], they will all be constructed according to a similar design and subject to the dominion of One." Due to limitations on observational equipment, the field of exoplanetary systems existed primarily in theory until the late 1980s. -

Sulfur Hazes in Giant Exoplanet Atmospheres: Impacts on Reflected

Draft version February 28, 2017 Preprint typeset using LATEX style AASTeX6 v. 1.0 SULFUR HAZES IN GIANT EXOPLANET ATMOSPHERES: IMPACTS ON REFLECTED LIGHT SPECTRA Peter Gao1,2,3, Mark S. Marley, and Kevin Zahnle NASA Ames Research Center Moffett Field, CA 94035, USA Tyler D. Robinson4,5 Department of Astronomy and Astrophysics University of California Santa Cruz Santa Cruz, CA 95064, USA Nikole K. Lewis Space Telescope Science Institute Baltimore, MD 21218, USA 1Division of Geological and Planetary Sciences, California Institute of Technology, Pasadena, CA 91125, USA 2NASA Postdoctoral Program Fellow [email protected] 4Sagan Fellow 5NASA Astrobiology Institute’s Virtual Planetary Laboratory ABSTRACT Recent work has shown that sulfur hazes may arise in the atmospheres of some giant exoplanets due to the photolysis of H2S. We investigate the impact such a haze would have on an exoplanet’s geometric albedo spectrum and how it may affect the direct imaging results of WFIRST, a planned NASA space telescope. For temperate (250 K < Teq < 700 K) Jupiter–mass planets, photochemical destruction of H2S results in the production of 1 ppmv of S8 between 100 and 0.1 mbar, which, if cool enough, ∼ will condense to form a haze. Nominal haze masses are found to drastically alter a planet’s geometric albedo spectrum: whereas a clear atmosphere is dark at wavelengths between 0.5 and 1 µm due to molecular absorption, the addition of a sulfur haze boosts the albedo there to 0.7 due to scattering. ∼ Strong absorption by the haze shortward of 0.4 µm results in albedos <0.1, in contrast to the high albedos produced by Rayleigh scattering in a clear atmosphere. -

Star Festival 2016 Parade & Exhibition

Jump!Star Festival 2016 Parade & Exhibition Images from George Ferrandi’s Wherever There is Water light parade for Fleisher Art Memorial 202.234.7103 Capitol Skyline Hotel [email protected] 10 I (Eye) Street SW www.wpadc.org Washington, DC 20024 TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION Jump!Star Festival Concept History of the Project Festival Narrative Artist’s Biography COMPONENTS Community Engagement Workshops Light Exhibition Parade/Festival Images from George Ferrandi’s Wherever There is Water light parade for Fleisher Art Memorial INTRODUCTION Images from George Ferrandi’s Wherever There is Water light parade for Fleisher Art Memorial The Jump!Star Festival is a participatory public art project created by artist George Ferrandi that will celebrate the temporal nature of our pole star, the “North Star,” by bringing the local community together with a light parade, music, food, and a culminating exhibition of light sculptures created by local artists. Key Dates Parade/Festival: September 24, 2016 Workshops: May/June/July/August 2016 Exhibition: September 20-25, 2016 History of the Project For the Northern Hemisphere, Polaris, or the “North Star” is the guiding light for 90% of the world’s population, yet this Pole Star, the anchor of our heavens, is not permanent. Because the earth rotates at a slight angle on its axis, there is a slight shift in its rotation so that what we consider our “North Star” changes every few thousand years. When the pyramids were built, for example, there was a different “North Star” reigning over the heavens. Very few realize that our quintessential point of reference and ever reliable, literal “Guiding Light” is a temporary gig. -

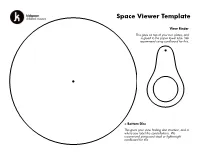

Space Viewer Template

Space Viewer Template View Finder This goes on top of your two plates, and is glued to the paper towel tube. We recommend using cardboard for this. < Bottom Disc This gives your view finding disc structure, and is where you label the constellations. We recommend using card stock or lightweight cardboard for this. Constellation Plate > This disc is home to your constellations, and gets glued to the larger disc. We recommend using paper for this, so the holes are easier to punch. Use the punch guides on the next page to punch holes and add labels to your viewer. Orion Cancer Look for the middle star of Orions When you look at this constellation, look sword, that is an area of brighter nearby for 55 Cancri a star that has light, it’s actually a nebula! The five exoplanets orbiting it. One of those Orion Nebula is a gigantic cloud of plants (55 Cancri e) is a super hot dust and gas, where new stars are planet entirely covered in an ocean of being created. lava! Cygnus Andromeda This constellation is home to the This constellation is very close to the Kepler-186 system, including the Andromeda Galaxy (an enormous planet Kepler-186f. Seen by collection of gas, dust, and billions of NASA's Kepler Space Telescope, stars and solar systems). This spiral this is the first Earth-sized planet galaxy is so bright, you can spot it with discovered that is in"habitable the naked eye! zone" of its star. Ursa Minor Cassiopeia Ursa Minor has two stars known While gazing at Cassiopeia look for with exoplanets orbiting them - the“Pacman Nebula” (It’s official name both are gas giants, that are much is NGC 281). -

Thursday, December 22Nd Swap Meet & Potluck Get-Together Next First

Io – December 2011 p.1 IO - December 2011 Issue 2011-12 PO Box 7264 Eugene Astronomical Society Annual Club Dues $25 Springfield, OR 97475 President: Sam Pitts - 688-7330 www.eugeneastro.org Secretary: Jerry Oltion - 343-4758 Additional Board members: EAS is a proud member of: Jacob Strandlien, Tony Dandurand, John Loper. Next Meeting: Thursday, December 22nd Swap Meet & Potluck Get-Together Our December meeting will be a chance to visit and share a potluck dinner with fellow amateur astronomers, plus swap extra gear for new and exciting equipment from somebody else’s stash. Bring some food to share and any astronomy gear you’d like to sell, trade, or give away. We will have on hand some of the gear that was donated to the club this summer, including mirrors, lenses, blanks, telescope parts, and even entire telescopes. Come check out the bargains and visit with your fellow amateur astronomers in a relaxed evening before Christmas. We also encourage people to bring any new gear or projects they would like to show the rest of the club. The meeting is at 7:00 on December 22nd at EWEB’s Community Room, 500 E. 4th in Eugene. Next First Quarter Fridays: December 2nd and 30th Our November star party was clouded out, along with a good deal of the month afterward. If that sounds familiar, that’s because it is: I changed the date in the previous sentence from October to November and left the rest of the sentence intact. Yes, our autumn weather is predictable. Here’s hoping for a lucky break in the weather for our two December star parties. -

Who Really Discovered the First Exoplanet?

Who Really Discovered the First Exoplanet? Two Swiss astronomers got a well-deserved Nobel for finding an exoplanet, but there’s an intriguing backstory By Josh Winn The year 1995, like 1492, was the dawn of an age of discovery. The new explorers, instead of using seagoing vessels to discover continents, use telescopes to discover planets revolving around distant stars. Thousands of these extrasolar planets, a term usually shortened to “exoplanets,” have been found, including a few potentially Earth- like worlds, along with bizarre objects that bear no resemblance to any of the planets in our solar system. Two of these exoplanet explorers, Michel Mayor and Didier Queloz, were recently awarded half of the Nobel Prize in Physics for the discovery they made in 1995. My colleagues and I are united in our admiration for their pioneering work, and in our pride to be continuing what they began. But there is something peculiar about the Nobel Prize citation. It says: “for the discovery of an exoplanet orbiting a solar-type star.” Shouldn’t it say the first exoplanet? After all, hundreds of astronomers have discovered an exoplanet. I’ve helped find a few. Even high school students and amateur astronomers have discovered them. Did the Nobel Committee make a typographical error? No, they did not, and thereby hangs a tale. Just as it is problematic to decide who discovered America (Christopher Columbus? John Cabot? Leif Erikson? Amerigo Vespucci, whose name is the one that stuck? Those who came on foot from Siberia tens of thousands of years ago?) it is difficult to say who discovered the first exoplanet. -

![Arxiv:2010.00015V3 [Hep-Ph] 26 Apr 2021 Galactic Halo Can Scatter with Exoplanets, Lose Energy, and Gles Are the Same Set of Planets, Without DM Heating](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2593/arxiv-2010-00015v3-hep-ph-26-apr-2021-galactic-halo-can-scatter-with-exoplanets-lose-energy-and-gles-are-the-same-set-of-planets-without-dm-heating-1662593.webp)

Arxiv:2010.00015V3 [Hep-Ph] 26 Apr 2021 Galactic Halo Can Scatter with Exoplanets, Lose Energy, and Gles Are the Same Set of Planets, Without DM Heating

MIT-CTP/5230 SLAC-PUB-17556 Exoplanets as Sub-GeV Dark Matter Detectors Rebecca K. Leane1, 2, ∗ and Juri Smirnov3, 4, y 1Center for Theoretical Physics, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA 02139, USA 2SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory, Stanford University, Stanford, CA 94039, USA 3Center for Cosmology and AstroParticle Physics (CCAPP), The Ohio State University, Columbus, OH 43210, USA 4Department of Physics, The Ohio State University, Columbus, OH 43210, USA (Dated: April 27, 2021) We present exoplanets as new targets to discover Dark Matter (DM). Throughout the Milky Way, DM can scatter, become captured, deposit annihilation energy, and increase the heat flow within exoplanets. We estimate upcoming infrared telescope sensitivity to this scenario, finding actionable discovery or exclusion searches. We find that DM with masses above about an MeV can be probed with exoplanets, with DM-proton and DM-electron scattering cross sections down to about 10−37cm2, stronger than existing limits by up to six orders of magnitude. Supporting evidence of a DM origin can be identified through DM-induced exoplanet heating correlated with Galactic position, and hence DM density. This provides new motivation to measure the temperature of the billions of brown dwarfs, rogue planets, and gas giants peppered throughout our Galaxy. Introduction{Are we alone in the Universe? This ques- Exoplanet Temperatures tion has driven wide-reaching interest in discovering a 104 planet like our own. Regardless of whether or not we ever find alien life, the scientific advances from finding DM Heating and understanding other planets will be enormous. From a particle physics perspective, new celestial bodies pro- vide a vast playground to discover new physics. -

Planet Formation in Binaries 3

Noname manuscript No. (will be inserted by the editor) Planet formation in Binaries P. Thebault · N. Haghighipour the date of receipt and acceptance should be inserted later Abstract Spurred by the discovery of more than 60 exoplanets in multiple systems, binaries have become in recent years one of the main topics in planet formation re- search. Numerous studies have investigated to what extent the presence of a stellar companion can affect the planet formation process. Such studies have implications that can reach beyond the sole context of binaries, as they allow to test certain as- pects of the planet formation scenario by submitting them to extreme environments. We review here the current understanding on this complex problem. We show in par- ticular how each of the different stages of the planet-formation process is affected differently by binary perturbations. We focus especially on the intermediate stage of kilometre-sized planetesimal accretion, which has proven to be the most sensitive to binarity and for which the presence of some exoplanets observed in tight binaries is difficult to explain by in-situ formation following the ”standard” planet-formation scenario. Some tentative solutions to this apparent paradox are presented. The last part of our review presents a thorough description of the problem of planet habit- ability, for which the binary environment creates a complex situation because of the presence of two irradiation sources of varying distance. Keywords Planetary systems · Binary Stars 1 Introduction About half of solar-type stars reside in multiple stellar systems (Raghavan et al., 2010). As a consequence, one of the most generic environments to be considered for studying planet formation should in principle be that of a binary. -

The Influences of the Companion Star for the Formation of the Gamma- Cephei Planetary System Ricardo

The influences of the companion star for the formation of the Gamma- Cephei planetary system Ricardo. A. Moraes and E. Vieira Neto Grupo de Dinâmica Orbital e Planetologia, Univ. Estadual Paulista – UNESP, Brazil The existence of planetary system inside multiple star systems are one of the most intriguing problems of the actual astronomy. With the advance of the observational methods several extrasolar planets was discovered in the past two decades, but the formation of these bodies remains cloudy. As well as the formation of planets in single stars systems, the planets of our Solar System for example, there is many theories for the formation of planets in multiple star systems, but the validation of these theories are often rare, in other words, although there are many theories for describe the formation of these planetary systems, but just a few of then are reliable. In the present work we will investigate the partial formation and migration of the planet Gamma-Cephei b, the only planet of a peculiar binary system called Gamma-Cephei. This system was choosed because the separation between the more assive star and its companion is the smaller among all binary systems discovered. All the planets in binary systems already discovered are orbiting the more massive star, while the companion star acts as a perturber body, these type of orbits are called as S-type, if the planet is orbiting the two stars it is in a orbit called P-type. The secondary star could be a important piece to solve the puzzle of the formation of a planet in systems like Gamma-Cephei, once the separation between the stars is small, the gravitational effects of the secondary star should be strong enough to affect the region where the planet will form, which leads to change the planet formation and its migration. -

Reach for the Stars***

T1 T2 T3 T4 T5 SCORE: 150 / 150 + Bonus 2 KEY: Alternative, acceptable answers are given in brackets Bonus: Name NASA’s 6 space shuttles – 1 bonus point per 3 correct answers. (2 pts total) Atlantis Challenger Columbia Discovery Endeavour Enterprise TEAM NAME/NUMBER: _____________________________________________________________, #__________ COMPETITORS’ NAMES: _________________________________________________ __________________________________________________ Time is NOT a tiebreaker. Tiebreakers will be the individual section scores, in this order: Ic, Ia, IIb, Ib, Id, IIa. Some questions are designated as further tiebreakers. You have 50 minutes to complete this test to the best of your ability. Good luck. Go! ***Reach for the Stars*** 1 SECTION Ia: Identify the DSOs on the image sheet (letters on the image sheet correspond to the letters below) and answer the accompanying questions (1 pt each, 35 pts total). A. Cas A i. This DSO is the strongest source (outside of our solar system) of what kind of electromagnetic radiation? Radio (waves) B. Veil Nebula i. What is an alternate name for this DSO? (Hint: has to do with a constellation.) Cygnus Loop C. Andromeda Galaxy i. What is this DSO’s Messier catalog number? M31 [31] ii. Which other DSO is likely to collide with this DSO in about 2.5 million years? Milky Way Galaxy D. Pleiades i. Approximately how old are the stars in this DSO? Accept 75-150 million years ii. What constellation is this DSO found in? Taurus E. Crab Nebula i. What object causes this DSO’s x-ray emissions? Crab Pulsar [neutron star, pulsar] ii. When was the supernova that created this nebula seen from Earth? 1054 F. -

1455189355674.Pdf

THE STORYTeller’S THESAURUS FANTASY, HISTORY, AND HORROR JAMES M. WARD AND ANNE K. BROWN Cover by: Peter Bradley LEGAL PAGE: Every effort has been made not to make use of proprietary or copyrighted materi- al. Any mention of actual commercial products in this book does not constitute an endorsement. www.trolllord.com www.chenaultandgraypublishing.com Email:[email protected] Printed in U.S.A © 2013 Chenault & Gray Publishing, LLC. All Rights Reserved. Storyteller’s Thesaurus Trademark of Cheanult & Gray Publishing. All Rights Reserved. Chenault & Gray Publishing, Troll Lord Games logos are Trademark of Chenault & Gray Publishing. All Rights Reserved. TABLE OF CONTENTS THE STORYTeller’S THESAURUS 1 FANTASY, HISTORY, AND HORROR 1 JAMES M. WARD AND ANNE K. BROWN 1 INTRODUCTION 8 WHAT MAKES THIS BOOK DIFFERENT 8 THE STORYTeller’s RESPONSIBILITY: RESEARCH 9 WHAT THIS BOOK DOES NOT CONTAIN 9 A WHISPER OF ENCOURAGEMENT 10 CHAPTER 1: CHARACTER BUILDING 11 GENDER 11 AGE 11 PHYSICAL AttRIBUTES 11 SIZE AND BODY TYPE 11 FACIAL FEATURES 12 HAIR 13 SPECIES 13 PERSONALITY 14 PHOBIAS 15 OCCUPATIONS 17 ADVENTURERS 17 CIVILIANS 18 ORGANIZATIONS 21 CHAPTER 2: CLOTHING 22 STYLES OF DRESS 22 CLOTHING PIECES 22 CLOTHING CONSTRUCTION 24 CHAPTER 3: ARCHITECTURE AND PROPERTY 25 ARCHITECTURAL STYLES AND ELEMENTS 25 BUILDING MATERIALS 26 PROPERTY TYPES 26 SPECIALTY ANATOMY 29 CHAPTER 4: FURNISHINGS 30 CHAPTER 5: EQUIPMENT AND TOOLS 31 ADVENTurer’S GEAR 31 GENERAL EQUIPMENT AND TOOLS 31 2 THE STORYTeller’s Thesaurus KITCHEN EQUIPMENT 35 LINENS 36 MUSICAL INSTRUMENTS