Chapter 5: Memorization of the Armenian Genocide in Cultural Narratives1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Diatope and La L ´Egende D'eer

Elisavet Kiourtsoglou An Architect Draws Sound 13 rue Clavel, 75019, Paris, France [email protected] and Light: New Perspectives on Iannis Xenakis’s Diatope and La Legende´ d’Eer (1978) Abstract: This article examines the creative process of Diatope, a multimedia project created by Iannis Xenakis in 1978 for the inauguration of the Centre Pompidou in Paris, utilizing analytical research of sources found in several archives. By interpreting Xenakis’s sketches and plans, the article elucidates for the first time the spatialization of La Legende´ d’Eer, the music featured in the Diatope. The findings of the research underline the importance of graphic and geometric representation for understanding Xenakis’s thinking, and they highlight the continuity and evolution of his theory and practice over time. Furthermore, the research findings present the means by which this key work of electroacoustic music might be spatialized today, now that the original space of the Diatope no longer exists. Iannis Xenakis (1922–2001) was trained as a civil distinct levels of Diatope—architecture, music, and engineer at the Polytechnic University of Athens light—were neither interdependent elements of the (NTUA) and became an architect during his collab- work nor merely disparate artistic projects merged oration with Le Corbusier (1947–1959). Later on, together. Xenakis presented a four-dimensional Xenakis devoted himself mainly to the composition spectacle based upon analogies between diverse of music, with the exception of purely architectural aspects of space–time reality. To achieve this he projects sporadically conceived for his friends and used elementary geometry (points and lines) as a for other composers. -

This Electronic Thesis Or Dissertation Has Been Downloaded from Explore Bristol Research

This electronic thesis or dissertation has been downloaded from Explore Bristol Research, http://research-information.bristol.ac.uk Author: Vagopoulou, Evaggelia Title: Cultural tradition and contemporary thought in Iannis Xenakis's vocal works General rights Access to the thesis is subject to the Creative Commons Attribution - NonCommercial-No Derivatives 4.0 International Public License. A copy of this may be found at https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/legalcode This license sets out your rights and the restrictions that apply to your access to the thesis so it is important you read this before proceeding. Take down policy Some pages of this thesis may have been removed for copyright restrictions prior to having it been deposited in Explore Bristol Research. However, if you have discovered material within the thesis that you consider to be unlawful e.g. breaches of copyright (either yours or that of a third party) or any other law, including but not limited to those relating to patent, trademark, confidentiality, data protection, obscenity, defamation, libel, then please contact [email protected] and include the following information in your message: •Your contact details •Bibliographic details for the item, including a URL •An outline nature of the complaint Your claim will be investigated and, where appropriate, the item in question will be removed from public view as soon as possible. Cultural Tradition and Contemporary Thought in lannis Xenakis's Vocal Works Volume I: Thesis Text Evaggelia Vagopoulou A dissertation submitted to the University of Bristol in accordancewith the degree requirements of the of Doctor of Philosophy in the Faculty of Arts, Music Department. -

Rethinking Genocide: Violence and Victimhood in Eastern Anatolia, 1913-1915

Rethinking Genocide: Violence and Victimhood in Eastern Anatolia, 1913-1915 by Yektan Turkyilmaz Department of Cultural Anthropology Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Orin Starn, Supervisor ___________________________ Baker, Lee ___________________________ Ewing, Katherine P. ___________________________ Horowitz, Donald L. ___________________________ Kurzman, Charles Dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Cultural Anthropology in the Graduate School of Duke University 2011 i v ABSTRACT Rethinking Genocide: Violence and Victimhood in Eastern Anatolia, 1913-1915 by Yektan Turkyilmaz Department of Cultural Anthropology Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Orin Starn, Supervisor ___________________________ Baker, Lee ___________________________ Ewing, Katherine P. ___________________________ Horowitz, Donald L. ___________________________ Kurzman, Charles An abstract of a dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Cultural Anthropology in the Graduate School of Duke University 2011 Copyright by Yektan Turkyilmaz 2011 Abstract This dissertation examines the conflict in Eastern Anatolia in the early 20th century and the memory politics around it. It shows how discourses of victimhood have been engines of grievance that power the politics of fear, hatred and competing, exclusionary -

CONTENTS CAIA NEWS ARMENIAN SENIOR CITIZENS at HAYASHEN CAIA TAKES PART in REFUGEES CONFERENCE COMMUNITY NEWS Page 1 of 29 Armen

Armenian Voice: Issue 53, Summer 2008 Page 1 of 29 Summer 2008 Issue 53 CONTENTS • CAIA NEWS ◦ CAIA Purchases New Minibus ◦ CAIA Annual General Meeting ◦ CAIA Welcomes Mr Tim Cook ◦ Training Courses at CAIA ◦ Easter Celebrations at Hayashen ◦ History Memory & the Armenian Genocide ◦ London Councils Stop Funding CAIA Advisory Services ◦ Hayashen Youth Club Events ◦ Pre-School Group Xmas Party ◦ Parents and Toddlers Visit Dolls Exhibition ◦ Thank You All To All Our Donors • ARMENIAN SENIOR CITIZENS AT HAYASHEN ◦ Senior Citizens Christmas Party ◦ Engaging Armenian Senior Citizens & Their Carers ◦ Exercise Classes ◦ Heath Advocacy & Outreach Services for Older People • CAIA TAKES PART IN REFUGEES CONFERENCE ◦ Conference Highlighting the Suffering of "Invisible" Older Refugees • COMMUNITY NEWS ◦ Armenian Memorial Stone Vandalised ◦ Armenian Mothers Day Celebrated ◦ New Armenian Embassy Website http://caia.org.uk/armenianvoice/53/index.htm 11/09/2010 Armenian Voice: Issue 53, Summer 2008 Page 2 of 29 ◦ Bishop Hovhannisian Addresses Members of Parliament ◦ Play "Beast On The Moon" ◦ Film "The Lark Farm" ◦ Anniversary of the Assasination of Hrant Dink ◦ Guardian Weekend MAgazine ◦ Exhibition of Armenian Lettering in Lincoln ◦ AYA Football Club - A Grand Year • NEWS IN BRIEF: DIASPORA & ARMENIA ◦ Various Stories of Armenian Interest • BOOK REVIEWS ◦ "The Great Game of Genocide" ◦ "The Armenian Genocide: Cultural and Ethical Legacies" ◦ "Democracy Building & Civil Society in Post-Soviet Armenia" ◦ "My Brother's Road" ◦ "My Grandmother" CAIA NEWS CAIA PURCHASES NEW MINIBUS On Friday 6th June 2008, at Hayashen , over 50 delighted Armenian senior citizens and carers welcomed the delivery of a new 15-seat vehicle purchased by the CAIA for the benefit of frail, elderly, and disabled Armenians. -

Iannis Xenakis - in Memoriam (Cyprus, 3-5 Nov 11)

Iannis Xenakis - in Memoriam (Cyprus, 3-5 Nov 11) Nicosia, Cyprus, Nov 3–05, 2011 Deadline: Jun 15, 2011 Olga Touloumi, Harvard University Call for Papers: Iannis Xenakis - in Memoriam International Conference Iannis Xenakis is one of the most celebrated composers and iconic figures of the twentieth century. He was one of the most influential thinkers of the past century not only in the field of music but also in various scientific pursuits. His music and philosophy have inspired a whole generation of composers and performers, and this conference, which coincides with the ten-year anniversary of his death, aims to shed light on lesser-known aspects of his life and work. The Department of Arts of the European University Cyprus is proud to announce a Call for papers, performances and site specific musical installations for The Iannis Xenakis - in Memoriam International Conference to take place at European University Cyprus on 3, 4 & 5 November 2011. We invite composers, performers and musicologists - as well as architectural and art historians - to Cyprus, an island that has been a geographical and cultural cross point throughout its history, to pay tribute to this great thinker. The presentations should not exceed 20 minutes. 10 minutes will be allocated for further discussion and questions following each presentation. Proposed performances of Xenakis' works should last no longer than 40 minutes, and details about the scale of installations are available upon request (see below for contact details). Those interested should send a 300 word abstract (or performance samples for performers) as well as a short biography (250 words maximum) by 15 June 2011 to Dr Evis Sammoutis at [email protected] with the subject line Iannis Xenakis - in Memoriam International Conference. -

The Necrogeography of the Armenian Genocide in Dayr Al-Zur, Syria

i i i Bone memory: the necrogeography i of the Armenian Genocide in Dayr al-Zur, Syria HUMAN REMAINS & VIOLENCE Elyse Semerdjian Whitman College [email protected] Abstract This article discusses how Armenians have collected, displayed and exchanged the bones of their murdered ancestors in formal and informal ceremonies of remem- brance in Dayr al-Zur, Syria – the nal destination for hundreds of thousands of Armenians during the deportations of 1915. These pilgrimages – replete with overlapping secular and nationalist motifs – are a modern variant of historical pil- grimage practices; yet these bones are more than relics. Bone rituals, displays and vernacular memorials are enacted in spaces of memory that lie outside of ocial state memorials, making unmarked sites of atrocity more legible. Vernacular memo- rial practices are of particular interest as we consider new archives for the history of the Armenian Genocide. The rehabilitation of this historical site into public con- sciousness is particularly urgent, since the Armenian Genocide Memorial Museum and Martyr’s Church at the centre of the pilgrimage site were both destroyed by ISIS (Islamic State in Syria) in 2014. Key words: Armenian Genocide, pilgrimage, memory, memorials, Syria, ISIS ‘I wanted to bond with our people’s grief, to make it part of my body and conscious- ness ::: I wanted to go from Lebanon to Dayr al-Zur – that immense graveyard of our martyrs.’ Armenian poet Hamasdegh wrote these words in an essay titled ‘With a Skull’ aer his own pilgrimage in the Syrian desert in 1929. The essay described ‘ribs ripped apart from spinal columns, knee caps and skulls’,scattered fragments of bone comingling and protruding from the soil. -

An Exploration of Conflict in the Life and Works of Iannis Xenakis

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons CUREJ - College Undergraduate Research Electronic Journal College of Arts and Sciences 3-28-2014 Mollifying the Muses: An Exploration of Conflict in the Life and Works of Iannis Xenakis Davis S. Butner [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/curej Part of the Architectural History and Criticism Commons, Composition Commons, Music Performance Commons, Other Architecture Commons, and the Other Music Commons Recommended Citation Butner, Davis S., "Mollifying the Muses: An Exploration of Conflict in the Life and Works of Iannis Xenakis" 28 March 2014. CUREJ: College Undergraduate Research Electronic Journal, University of Pennsylvania, https://repository.upenn.edu/curej/182. This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/curej/182 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Mollifying the Muses: An Exploration of Conflict in the Life and Works of Iannis Xenakis Abstract The early life of Iannis Xenakis, a modern day Renaissance scholar who would come to redefine the limits of musical composition and sound-driven spatial design in the 21st century, was overshadowed by adversity, conflict and alienation. Fleeing from his home country in 1947 after a nearly fatal wound to the face during the Greek Revolution, Xenakis' newfound life and career in the atelier of French architect Le Corbusier allowed for the budding engineer to explore a collective passion for music and mathematics within his work. Nevertheless, just as a giant facial scar would stand as a permanent physical symbol for the brutality Xenakis experienced, one can easily detect similar memories of a chaotic past embedded in the compositional framework of the avant-garde designer/composer, tormented by tension and estranged symbols of war. -

Evangelical Theological Seminary of Armenia

Publication of the Armenian Missionary Association of America JAN/FEB 2001 - Vol. XXXV No. 1 (ISSN 1097-0924) Evangelical Theological Seminary of Armenia - Class of 2000 E D I T O R I A L M E S S A G E On the 1700th Anniversary of Armenian Christianity Some Reflections on the Great Event by Barkev N. Darakjian * here are events and peoples in the his- of the Christianization of Armenia should came second Ttory of nations which set most impor- be Christocentric rather than centered on to his mission tant and definitive milestones in their con- Armenian culture, politics, or even on the of evangelism. sciousness as well as in their national expe- church itself. This has to be our norm and He evange- rience. The Christianization of Armenia be- criterion while we try to evaluate that great lized because came a turning point in the history of Ar- event. As Anselm, the great archbishop of he believed that he was sent to Armenia to menia and the Armenians. After accepting Canterbury (1033-1109) says, “I believe, in evangelize; that was his calling. Even though Christianity as its national or State religion, order that I may understand.” Personal faith he was a Parthian by race, he loved Arme- Armenia was never the same religiously, in Jesus Christ is of paramount importance nia, having been brought up as an Arme- culturally, and politically. It is futile to raise if we want to understand the conversion of nian. Probably he had some foreboding questions such as, what would have hap- Armenia to Christianity. -

Analysing the First Electroacoustic Music of Iannis Xenakis Makis Solomos

Analysing the First Electroacoustic Music of Iannis Xenakis Makis Solomos To cite this version: Makis Solomos. Analysing the First Electroacoustic Music of Iannis Xenakis. 5th European Music Analysis Conference, 2002, Bristol, United Kingdom. hal-02055242 HAL Id: hal-02055242 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02055242 Submitted on 3 Mar 2019 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Analysing the First Electroacoustic Music of Iannis Xenakis 5th European Music Analysis Conference, Bristol, April 2002 Makis Solomos Université Montpellier 3, Institut Universitaire de France [email protected] XENAKIS’ ELECTROACOUSTIC MUSIC AND ANALYSIS The number of electroacoustic works produced by Iannis Xenakis represents only a slight percentage of his overall output: about one-tenth, including the few mixed-media pieces coupling instruments with tape. Nevertheless, their importance is enormous at least for two reasons. First, like Stockhausen or Berio, Xenakis was one of the firsts to compose electroacoustic music in the historical sense of the word, filling the gap between the two antagonistic trends of the early fifties: the concrète and the electronic approach. Second, unlike Berio, who after some early works stopped composing for tape, Xenakis continued to do so; and unlike Stockhausen who did follow the dramatic evolution of this relatively new musical genre, Xenakis also significantly contributed to its technology. -

Xenakis's Early Works: from “Bartókian Project” to "Abstraction"

Xenakis’s Early Works: From ” Bartókian Project ” to ”Abstraction” Makis Solomos To cite this version: Makis Solomos. Xenakis’s Early Works: From ” Bartókian Project ” to ”Abstraction”. Contemporary Music Review, Taylor & Francis, 2002, vol. 21 (n°2-3), p. 21-34. hal-01202924 HAL Id: hal-01202924 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01202924 Submitted on 21 Sep 2015 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Xenakis's Early Works: From “Bartókian Project” to "Abstraction" Makis Solomos 1. Xenakis's "Early" and "First" Compositions During the “coup d'état”1 which, with Metastaseis (1953-54) and Pithoprakta (1955- 56), bypassed the serial avant-garde—an avant-garde which was proclaiming that "any composer out of the field of serial research is useless"2—thanks to the invention of radically new and "abstract" techniques, Iannis Xenakis appeared as an ex nihilo creator. The perspective of a tabula rasa, with which Xenakis simulates "amnesia," is certainly part of his theoretical intention.3 His musical output, however, partially negates this perspective. In the framework of the present article, it would be difficult to defend this opinion in relation to the whole of post-1945 musical history. -

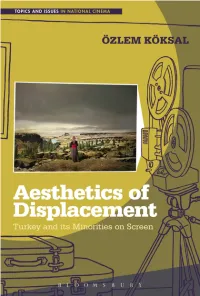

Aesthetics of Displacement Topics and Issues in National Cinema Volume 4 Aesthetics of Displacement: Turkey and Its Minorities on Screen

Aesthetics of Displacement Topics and Issues in National Cinema volume 4 Aesthetics of Displacement: Turkey and its Minorities on Screen Series Editor: Armida de la Garza, University College Cork, Ireland Editorial Board: Mette Hjort, Chair Professor and Head, Visual Studies Lingnan University, Hong Kong Lúcia Nagib, Professor of Film, University of Reading, UK Chris Berry, Professor of Film Studies, Kings College London, UK, and Co-Director of the Goldsmiths Leverhulme Media Research Centre, UK Sarah Street, Professor of Film and Foundation Chair of Drama, University of Bristol, UK Jeanette Hoorn, Professor of Visual Cultures, University of Melbourne, Australia Shohini Chaudhuri, Senior Lecturer and MA Director in Film Studies, University of Essex, UK Other volumes in the series: Volume 1: Revolution and Rebellion in Mexican Film by Niamh Th ornton Volume 2: Ecology and Contemporary Nordic Cinemas: From Nation-Building to Ecocosmopolitanism by Pietari Kääpä Volume 3: Cypriot Cinemas edited by Costas Constandinides and Yiannis Papadakis Volume 4: Aesthetics of Displacement by Özlem Köksal Volume 5: Film Music in ‘Minor’ National Cinemas edited by Germán Gil-Curiel Aesthetics of Displacement: Turkey and its Minorities on Screen Özlem Köksal Bloomsbury Academic An imprint of Bloomsbury Publishing Inc Bloomsbury Academic An imprint of Bloomsbury Publishing Inc 1385 Broadway 50 Bedford Square New York London NY 10018 WC1B 3DP USA UK www.bloomsbury.com BLOOMSBURY and the Diana logo are trademarks of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc First published 2016 Paperback edition fi rst published 2017 © Özlem Köksal, 2016 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publishers. -

Music of Sound and Light: Xenakis's Polytopes Author(S): Maria Anna Harley Source: Leonardo, Vol

Music of Sound and Light: Xenakis's Polytopes Author(s): Maria Anna Harley Source: Leonardo, Vol. 31, No. 1 (1998), pp. 55-65 Published by: The MIT Press Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/1576549 Accessed: 02/11/2008 10:07 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=mitpress. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. JSTOR is a not-for-profit organization founded in 1995 to build trusted digital archives for scholarship. We work with the scholarly community to preserve their work and the materials they rely upon, and to build a common research platform that promotes the discovery and use of these resources. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. The MIT Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Leonardo. http://www.jstor.org HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVE Music of Sound and Light: Xenakis's Polytopes Maria Anna Harley ABSTRACT Thisarticle explores the au- diovisualinstallations of Greek composerand architect lannis Xenakis,focusing on the works IN A MUSICAL UNIVERSE electroacoustic composition by hecalls "polytopes." The term Varese and a visual Le thecomplexity And when I lookedup at the infinite sky, the universecontem- display by polytopecaptures Corbusier.