Arxiv:1407.1054V2 [Astro-Ph.GA] 13 Oct 2014 Is Critical for Understanding the Assembly of Galaxies and Sipationless Merging and Accretion (E.G., De Lucia Et Al

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Lack of Evidence for Global Ram-Pressure Induced Star Formation in the Merging Cluster Abell 3266

Draft version March 31, 2021 Typeset using LATEX default style in AASTeX62 A Lack of Evidence for Global Ram-pressure Induced Star Formation in the Merging Cluster Abell 3266 Mark J. Henriksen1 and Scott Dusek1 1University of Maryland, Baltimore County Physics Department 1000 Hilltop Circle Baltimore, MD USA ABSTRACT Interaction between the intracluster medium and the interstellar media of galaxies via ram-pressure stripping (RPS) has ample support from both observations and simulations of galaxies in clusters. Some, but not all of the observations and simulations show a phase of increased star formation compared to normal spirals. Examples of galaxies undergoing RPS induced star formation in clusters experiencing a merger have been identified in high resolution optical images supporting the existence of a star formation phase. We have selected Abell 3266 to search for ram-pressure induced star formation as a global property of a merging cluster. Abell 3266 (z = 0.0594) is a high mass cluster that features a high velocity dispersion, an infalling subcluster near to the line of sight, and a strong shock front. These phenomena should all contribute to making Abell 3266 an optimum cluster to see the global effects of RPS induced star formation. Using archival X-ray observations and published optical data, we cross-correlate optical spectral properties ([OII, Hβ]), indicative of starburst and post-starburst, respectively with ram-pressure, ρv2, calculated from the X-ray and optical data. We find that post- starburst galaxies, classified as E+A, occur at a higher frequency in this merging cluster than in the Coma cluster and at a comparable rate to intermediate redshift clusters. -

The Local Radio-Galaxy Population at 20

Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 000, 1–?? (2013) Printed 2 December 2013 (MN LATEX style file v2.2) The local radio-galaxy population at 20GHz Elaine M. Sadler1⋆, Ronald D. Ekers2, Elizabeth K. Mahony3, Tom Mauch4,5, Tara Murphy1,6 1Sydney Institute for Astronomy, School of Physics, The University of Sydney, NSW 2006, Australia 2Australia Telescope National Facility, CSIRO, PO Box 76, Epping, NSW 1710, Australia 3ASTRON, the Netherlands Institute for Radio Astronomy, Postbus 2, 7990 AA, Dwingeloo, The Netherlands 4Oxford Astrophysics, Department of Physics, Keble Road, Oxford OX1 3RH 5SKA Africa, 3rd Floor, The Park, Park Road, Pinelands, 7405, South Africa 6School of Information Technologies, The University of Sydney, NSW 2006, Australia Accepted 0000 December 08. Received 0000 December 08; in original form 0000 December 08 ABSTRACT We have made the first detailed study of the high-frequency radio-source population in the local universe, using a sample of 202 radio sources from the Australia Telescope 20GHz (AT20G) survey identified with galaxies from the 6dF Galaxy Survey (6dFGS). The AT20G- 6dFGS galaxies have a median redshift of z=0.058 and span a wide range in radio luminosity, allowing us to make the first measurement of the local radio luminosity function at 20GHz. Our sample includes some classical FR-1 and FR-2 radio galaxies, but most of the AT20G-6dFGS galaxies host compact (FR-0) radio AGN which appear lack extended radio emission even at lower frequencies. Most of these FR-0 sources show no evidence for rela- tivistic beaming, and the FR-0 class appears to be a mixed population which includes young Compact Steep-Spectrum (CSS) and Gigahertz-Peaked Spectrum (GPS) radio galaxies. -

Infrared Spectroscopy of Nearby Radio Active Elliptical Galaxies

The Astrophysical Journal Supplement Series, 203:14 (11pp), 2012 November doi:10.1088/0067-0049/203/1/14 C 2012. The American Astronomical Society. All rights reserved. Printed in the U.S.A. INFRARED SPECTROSCOPY OF NEARBY RADIO ACTIVE ELLIPTICAL GALAXIES Jeremy Mould1,2,9, Tristan Reynolds3, Tony Readhead4, David Floyd5, Buell Jannuzi6, Garret Cotter7, Laura Ferrarese8, Keith Matthews4, David Atlee6, and Michael Brown5 1 Centre for Astrophysics and Supercomputing Swinburne University, Hawthorn, Vic 3122, Australia; [email protected] 2 ARC Centre of Excellence for All-sky Astrophysics (CAASTRO) 3 School of Physics, University of Melbourne, Melbourne, Vic 3100, Australia 4 Palomar Observatory, California Institute of Technology 249-17, Pasadena, CA 91125 5 School of Physics, Monash University, Clayton, Vic 3800, Australia 6 Steward Observatory, University of Arizona (formerly at NOAO), Tucson, AZ 85719 7 Department of Physics, University of Oxford, Denys, Oxford, Keble Road, OX13RH, UK 8 Herzberg Institute of Astrophysics Herzberg, Saanich Road, Victoria V8X4M6, Canada Received 2012 June 6; accepted 2012 September 26; published 2012 November 1 ABSTRACT In preparation for a study of their circumnuclear gas we have surveyed 60% of a complete sample of elliptical galaxies within 75 Mpc that are radio sources. Some 20% of our nuclear spectra have infrared emission lines, mostly Paschen lines, Brackett γ , and [Fe ii]. We consider the influence of radio power and black hole mass in relation to the spectra. Access to the spectra is provided here as a community resource. Key words: galaxies: elliptical and lenticular, cD – galaxies: nuclei – infrared: general – radio continuum: galaxies ∼ 1. INTRODUCTION 30% of the most massive galaxies are radio continuum sources (e.g., Fabbiano et al. -

The MASSIVE Survey-VIII. Stellar Velocity Dispersion Profiles And

MNRAS 000,1{17 (2017) Preprint 26 October 2017 Compiled using MNRAS LATEX style file v3.0 The MASSIVE Survey - VIII. Stellar Velocity Dispersion Profiles and Environmental Dependence of Early-Type Galaxies Melanie Veale,1;2? Chung-Pei Ma,1;2? Jenny E. Greene,3 Jens Thomas,4 John P. Blakeslee,5 Jonelle L. Walsh,6 Jennifer Ito1 1Department of Astronomy, University of California, Berkeley, CA 94720, USA 2Department of Physics, University of California, Berkeley, CA 94720, USA 3Department of Astrophysical Sciences, Princeton University, Princeton, NJ 08544, USA 4Max Plank-Institute for Extraterrestrial Physics, Giessenbachstr. 1, D-85741 Garching, Germany 5Dominion Astrophysical Observatory, NRC Herzberg Astronomy & Astrophysics, Victoria BC V9E2E7, Canada 6George P. and Cynthia Woods Mitchell Institute for Fundamental Physics and Astronomy, and Department of Physics and Astronomy, Texas A&M University, College Station, TX 77843, USA Accepted XXX. Received YYY; in original form ZZZ ABSTRACT We measure the radial profiles of the stellar velocity dispersions, σ¹Rº, for 90 early-type galaxies (ETGs) in the MASSIVE survey, a volume-limited integral-field spectroscopic (IFS) galaxy survey targeting all northern-sky ETGs with absolute K-band magnitude > 11 MK < −25:3 mag, or stellar mass M∗ ∼ 4 × 10 M , within 108 Mpc. Our wide-field 10700×10700 IFS data cover radii as large as 40 kpc, for which we quantify separately the inner (2 kpc) and outer (20 kpc) logarithmic slopes γinner and γouter of σ¹Rº. While γinner is mostly negative, of the 56 galaxies with sufficient radial coverage to determine γouter we find 36% to have rising outer dispersion profiles, 30% to be flat within the uncertainties, and 34% to be falling. -

V. Spatially-Resolved Stellar Angular Momentum, Velocity Dispersion, and Higher Moments of the 41 Most Massive Local Early-Type Galaxies

MNRAS 000,1{20 (2016) Preprint 9 September 2016 Compiled using MNRAS LATEX style file v3.0 The MASSIVE Survey - V. Spatially-Resolved Stellar Angular Momentum, Velocity Dispersion, and Higher Moments of the 41 Most Massive Local Early-Type Galaxies Melanie Veale,1;2 Chung-Pei Ma,1 Jens Thomas,3 Jenny E. Greene,4 Nicholas J. McConnell,5 Jonelle Walsh,6 Jennifer Ito,1 John P. Blakeslee,5 Ryan Janish2 1Department of Astronomy, University of California, Berkeley, CA 94720, USA 2Department of Physics, University of California, Berkeley, CA 94720, USA 3Max Plank-Institute for Extraterrestrial Physics, Giessenbachstr. 1, D-85741 Garching, Germany 4Department of Astrophysical Sciences, Princeton University, Princeton, NJ 08544, USA 5Dominion Astrophysical Observatory, NRC Herzberg Institute of Astrophysics, Victoria BC V9E2E7, Canada 6George P. and Cynthia Woods Mitchell Institute for Fundamental Physics and Astronomy, and Department of Physics and Astronomy, Texas A&M University, College Station, TX 77843, USA Accepted XXX. Received YYY; in original form ZZZ ABSTRACT We present spatially-resolved two-dimensional stellar kinematics for the 41 most mas- ∗ 11:8 sive early-type galaxies (MK . −25:7 mag, stellar mass M & 10 M ) of the volume-limited (D < 108 Mpc) MASSIVE survey. For each galaxy, we obtain high- quality spectra in the wavelength range of 3650 to 5850 A˚ from the 246-fiber Mitchell integral-field spectrograph (IFS) at McDonald Observatory, covering a 10700 × 10700 field of view (often reaching 2 to 3 effective radii). We measure the 2-D spatial distri- bution of each galaxy's angular momentum (λ and fast or slow rotator status), velocity dispersion (σ), and higher-order non-Gaussian velocity features (Gauss-Hermite mo- ments h3 to h6). -

Jet-Induced Star Formation in 3C 285 and Minkowski's Object⋆

A&A 574, A34 (2015) Astronomy DOI: 10.1051/0004-6361/201424932 & c ESO 2015 Astrophysics Jet-induced star formation in 3C 285 and Minkowski’s Object? Q. Salomé, P. Salomé, and F. Combes LERMA, Observatoire de Paris, CNRS UMR 8112, 61 avenue de l’Observatoire, 75014 Paris, France e-mail: [email protected] Received 5 September 2014 / Accepted 6 November 2014 ABSTRACT How efficiently star formation proceeds in galaxies is still an open question. Recent studies suggest that active galactic nucleus (AGN) can regulate the gas accretion and thus slow down star formation (negative feedback). However, evidence of AGN positive feedback has also been observed in a few radio galaxies (e.g. Centaurus A, Minkowski’s Object, 3C 285, and the higher redshift 4C 41.17). Here we present CO observations of 3C 285 and Minkowski’s Object, which are examples of jet-induced star formation. A spot (named 3C 285/09.6 in the present paper) aligned with the 3C 285 radio jet at a projected distance of ∼70 kpc from the galaxy centre shows star formation that is detected in optical emission. Minkowski’s Object is located along the jet of NGC 541 and also shows star formation. Knowing the distribution of molecular gas along the jets is a way to study the physical processes at play in the AGN interaction with the intergalactic medium. We observed CO lines in 3C 285, NGC 541, 3C 285/09.6, and Minkowski’s Object with the IRAM 30 m telescope. In the central galaxies, the spectra present a double-horn profile, typical of a rotation pattern, from which we are able to estimate the molecular gas density profile of the galaxy. -

Download (1MB)

This is an Open Access document downloaded from ORCA, Cardiff University's institutional repository: http://orca.cf.ac.uk/136213/ This is the author’s version of a work that was submitted to / accepted for publication. Citation for final published version: Smith, Mark D., Bureau, Martin, Davis, Timothy A., Cappellari, Michele, Liu, Lijie, Onishi, Kyoko, Iguchi, Satoru, North, Eve V. and Sarzi, Marc 2021. WISDOM project - VI. Exploring the relation between supermassive black hole mass and galaxy rotation with molecular gas. Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society 500 , pp. 1933-1952. 10.1093/mnras/staa3274 file Publishers page: http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/mnras/staa3274 <http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/mnras/staa3274> Please note: Changes made as a result of publishing processes such as copy-editing, formatting and page numbers may not be reflected in this version. For the definitive version of this publication, please refer to the published source. You are advised to consult the publisher’s version if you wish to cite this paper. This version is being made available in accordance with publisher policies. See http://orca.cf.ac.uk/policies.html for usage policies. Copyright and moral rights for publications made available in ORCA are retained by the copyright holders. MNRAS 500, 1933–1952 (2021) doi:10.1093/mnras/staa3274 Advance Access publication 2020 October 22 WISDOM project – VI. Exploring the relation between supermassive black hole mass and galaxy rotation with molecular gas Mark D. Smith ,1‹ Martin Bureau,1,2 Timothy A. Davis ,3 Michele Cappellari ,1 Lijie Liu,1 Kyoko Onishi ,4,5,6 Satoru Iguchi ,5,6 Eve V. -

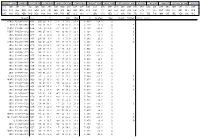

Bright Star Double Variable Globular Open Cluster Planetary Bright Neb Dark Neb Reflection Neb Galaxy Int:Pec Compact Galaxy Gr

bright star double variable globular open cluster planetary bright neb dark neb reflection neb galaxy int:pec compact galaxy group quasar ALL AND ANT APS AQL AQR ARA ARI AUR BOO CAE CAM CAP CAR CAS CEN CEP CET CHA CIR CMA CMI CNC COL COM CRA CRB CRT CRU CRV CVN CYG DEL DOR DRA EQU ERI FOR GEM GRU HER HOR HYA HYI IND LAC LEO LEP LIB LMI LUP LYN LYR MEN MIC MON MUS NOR OCT OPH ORI PAV PEG PER PHE PIC PSA PSC PUP PYX RET SCL SCO SCT SER1 SER2 SEX SGE SGR TAU TEL TRA TRI TUC UMA UMI VEL VIR VOL VUL Object ConRA Dec Mag z AbsMag Type Spect Filter Other names CFHQS J23291-0301 PSC 23h 29 8.3 - 3° 1 59.2 21.6 6.430 -29.5 Q ULAS J1319+0950 VIR 13h 19 11.3 + 9° 50 51.0 22.8 6.127 -24.4 Q I CFHQS J15096-1749 LIB 15h 9 41.8 -17° 49 27.1 23.1 6.120 -24.1 Q I FIRST J14276+3312 BOO 14h 27 38.5 +33° 12 41.0 22.1 6.120 -25.1 Q I SDSS J03035-0019 CET 3h 3 31.4 - 0° 19 12.0 23.9 6.070 -23.3 Q I SDSS J20541-0005 AQR 20h 54 6.4 - 0° 5 13.9 23.3 6.062 -23.9 Q I CFHQS J16413+3755 HER 16h 41 21.7 +37° 55 19.9 23.7 6.040 -23.3 Q I SDSS J11309+1824 LEO 11h 30 56.5 +18° 24 13.0 21.6 5.995 -28.2 Q SDSS J20567-0059 AQR 20h 56 44.5 - 0° 59 3.8 21.7 5.989 -27.9 Q SDSS J14102+1019 CET 14h 10 15.5 +10° 19 27.1 19.9 5.971 -30.6 Q SDSS J12497+0806 VIR 12h 49 42.9 + 8° 6 13.0 19.3 5.959 -31.3 Q SDSS J14111+1217 BOO 14h 11 11.3 +12° 17 37.0 23.8 5.930 -26.1 Q SDSS J13358+3533 CVN 13h 35 50.8 +35° 33 15.8 22.2 5.930 -27.6 Q SDSS J12485+2846 COM 12h 48 33.6 +28° 46 8.0 19.6 5.906 -30.7 Q SDSS J13199+1922 COM 13h 19 57.8 +19° 22 37.9 21.8 5.903 -27.5 Q SDSS J14484+1031 BOO -

A Lack of Evidence for Global Ram-Pressure Induced Star Formation in the Merging Cluster Abell 3266

International Journal of Astronomy and Astrophysics, 2021, 11, 95-132 https://www.scirp.org/journal/ijaa ISSN Online: 2161-4725 ISSN Print: 2161-4717 A Lack of Evidence for Global Ram-Pressure Induced Star Formation in the Merging Cluster Abell 3266 Mark J. Henriksen, Scott Dusek Physics Department, University of Maryland, Baltimore, MD, USA How to cite this paper: Henriksen, M.J. and Abstract Dusek, S. (2021) A Lack of Evidence for Global Ram-Pressure Induced Star Forma- Interaction between the intracluster medium and the interstellar media of ga- tion in the Merging Cluster Abell 3266. In- laxies via ram-pressure stripping (RPS) has ample support from both obser- ternational Journal of Astronomy and As- vations and simulations of galaxies in clusters. Some, but not all of the obser- trophysics, 11, 95-132. vations and simulations show a phase of increased star formation compared https://doi.org/10.4236/ijaa.2021.111007 to normal spirals. Examples of galaxies undergoing RPS induced star forma- Received: January 30, 2021 tion in clusters experiencing a merger have been identified in high resolution Accepted: March 23, 2021 optical images supporting the existence of a star formation phase. We have Published: March 26, 2021 selected Abell 3266 to search for ram-pressure induced star formation as a global property of a merging cluster. Abell 3266 (z = 0.0594) is a high mass Copyright © 2021 by author(s) and Scientific Research Publishing Inc. cluster that features a high velocity dispersion, an infalling subcluster near to This work is licensed under the Creative the line of sight, and a strong shock front. -

The Stellar Halos of Massive Elliptical Galaxies. Ii

The Astrophysical Journal, 776:64 (12pp), 2013 October 20 doi:10.1088/0004-637X/776/2/64 C 2013. The American Astronomical Society. All rights reserved. Printed in the U.S.A. THE STELLAR HALOS OF MASSIVE ELLIPTICAL GALAXIES. II. DETAILED ABUNDANCE RATIOS AT LARGE RADIUS Jenny E. Greene1,3, Jeremy D. Murphy1,4, Genevieve J. Graves1, James E. Gunn1, Sudhir Raskutti1, Julia M. Comerford2,4, and Karl Gebhardt2 1 Department of Astrophysics, Princeton University, Princeton, NJ 08540, USA 2 Department of Astronomy, UT Austin, 1 University Station C1400, Austin, TX 71712, USA Received 2013 June 24; accepted 2013 August 6; published 2013 September 26 ABSTRACT We study the radial dependence in stellar populations of 33 nearby early-type galaxies with central stellar velocity −1 dispersions σ∗ 150 km s . We measure stellar population properties in composite spectra, and use ratios of these composites to highlight the largest spectral changes as a function of radius. Based on stellar population modeling, the typical star at 2Re is old (∼10 Gyr), relatively metal-poor ([Fe/H] ≈−0.5), and α-enhanced ([Mg/Fe] ≈ 0.3). The stars were made rapidly at z ≈ 1.5–2 in shallow potential wells. Declining radial gradients in [C/Fe], which follow [Fe/H], also arise from rapid star formation timescales due to declining carbon yields from low-metallicity massive stars. In contrast, [N/Fe] remains high at large radius. Stars at large radius have different abundance ratio patterns from stars in the center of any present-day galaxy, but are similar to average Milky Way thick disk stars. -

Quantifying the Importance of Ram Pressure Stripping in a Galaxy

Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 000, 1–8 (2010) Printed 18 June 2018 (MN LATEX style file v2.2) Quantifying the Importance of Ram Pressure Stripping in a Galaxy Group at 100 Mpc E. Freeland1⋆, C. Sengupta2,3⋆, & J. H. Croston4⋆ 1George P. & Cynthia W. Mitchell Institute for Fundamental Physics and Astronomy, Department of Physics and Astronomy, Texas A&M University, College Station, TX 77843, USA 2Calar-Alto Observatory, Centro Astronomico Hispano Aleman, C/Jesus Durban Remon, 2-2 04004 Almeria, Spain 3Instituto de Astrofisica de Andalucia (CSIC), Glorieta de Astronomia s/n, 18008 Granada, Spain 4School of Physics and Astronomy, University of Southampton, Southampton, SO17 1SJ, UK Accepted 2010 July 17. Received 2010 July 12; in original form 2010 May 14 ABSTRACT We examine two members of the NGC 4065 group of galaxies: a bent-double (a.k.a. wide angle tail) radio source and an Hi deficient spiral galaxy. Models of the X-ray emitting intragroup gas and the bent-double radio source, NGC 4061, are used to probe the density of intergalactic gas in this group. Hi observations reveal an asymmetric, truncated distribution of Hi in spiral galaxy, UGC 07049, and the accompanying radio continuum emission reveals strong star formation. We examine the effectiveness of ram pressure stripping as a gas removal mechanism and find that it alone cannot account for the Hi deficiency that is observed in UGC 07049 unless this galaxy has passed −1 through the core of the group with a velocity of ∼ 800 km s . A combination of tidal and ram pressure stripping are necessary to produce the Hi deficiency and asymmetry in this galaxy. -

![Arxiv:1801.08245V2 [Astro-Ph.GA] 14 Feb 2018](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0220/arxiv-1801-08245v2-astro-ph-ga-14-feb-2018-1300220.webp)

Arxiv:1801.08245V2 [Astro-Ph.GA] 14 Feb 2018

Draft version June 21, 2021 Preprint typeset using LATEX style emulateapj v. 12/16/11 THE MASSIVE SURVEY IX: PHOTOMETRIC ANALYSIS OF 35 HIGH MASS EARLY-TYPE GALAXIES WITH HST WFC3/IR1 Charles F. Goullaud Department of Physics, University of California, Berkeley, CA, USA; [email protected] Joseph B. Jensen Utah Valley University, Orem, UT, USA John P. Blakeslee Herzberg Astrophysics, Victoria, BC, Canada Chung-Pei Ma Department of Astronomy, University of California, Berkeley, CA, USA Jenny E. Greene Princeton University, Princeton, NJ, USA Jens Thomas Max Planck-Institute for Extraterrestrial Physics, Garching, Germany. Draft version June 21, 2021 ABSTRACT We present near-infrared observations of 35 of the most massive early-type galaxies in the local universe. The observations were made using the infrared channel of the Hubble Space Telescope (HST ) Wide Field Camera 3 (WFC3) in the F110W (1.1 µm) filter. We measured surface brightness profiles and elliptical isophotal fit parameters from the nuclear regions out to a radius of ∼10 kpc in most cases. We find that 37% (13) of the galaxies in our sample have isophotal position angle rotations greater than 20◦ over the radial range imaged by WFC3/IR, which is often due to the presence of neighbors or multiple nuclei. Most galaxies in our sample are significantly rounder near the center than in the outer regions. This sample contains six fast rotators and 28 slow rotators. We find that all fast rotators are either disky or show no measurable deviation from purely elliptical isophotes. Among slow rotators, significantly disky and boxy galaxies occur with nearly equal frequency.