The Hermetic Frontispiece: Contextualising John Dee's Hieroglyphic Monad

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Alchemical Culture and Poetry in Early Modern England

Alchemical culture and poetry in early modern England PHILIP BALL Nature, 4–6 Crinan Street, London N1 9XW, UK There is a longstanding tradition of using alchemical imagery in poetry. It first flourished at the end of the sixteenth century, when the status of alchemy itself was revitalised in European society. Here I explain the reasons for this resurgence of the Hermetic arts, and explore how it was manifested in English culture and in particular in the literary and poetic works of the time. In 1652 the English scholar Elias Ashmole published a collection of alchemical texts called Theatrum Chymicum Britannicum, comprising ‘Several Poeticall Pieces of Our Most Famous English Philosophers’. Among the ‘chemical philosophers’ represented in the volume were the fifteenth-century alchemists Sir George Ripley and Thomas Norton – savants who, Ashmole complained, were renowned on the European continent but unduly neglected in their native country. Ashmole trained in law, but through his (second) marriage to a rich widow twenty years his senior he acquired the private means to indulge at his leisure a scholarly passion for alchemy and astrology. A Royalist by inclination, he had been forced to leave his London home during the English Civil War and had taken refuge in Oxford, the stronghold of Charles I’s forces. In 1677 he donated his impressive collection of antiquities to the University of Oxford, and the building constructed to house them became the Ashmolean, the first public museum in England. Ashmole returned to London after the civil war and began to compile the Theatrum, which was intended initially as a two-volume work. -

Alchemical Journey Into the Divine in Victorian Fairy Tales

Studia Religiologica 51 (1) 2018, s. 33–45 doi:10.4467/20844077SR.18.003.9492 www.ejournals.eu/Studia-Religiologica Alchemical Journey into the Divine in Victorian Fairy Tales Emilia Wieliczko-Paprota https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8662-6490 Institute of Polish Language and Literature University of Gdańsk [email protected] Abstract This article demonstrates the importance of alchemical symbolism in Victorian fairy tales. Contrary to Jungian analysts who conceived alchemy as forgotten knowledge, this study shows the vivid tra- dition of alchemical symbolism in Victorian literature. This work takes the readers through the first stage of the alchemical opus reflected in fairy tale symbols, explains the psychological and spiritual purposes of alchemy and helps them to understand the Victorian visions of mystical transforma- tion. It emphasises the importance of spirituality in Victorian times and accounts for the similarity between Victorian and alchemical paths of transformation of the self. Keywords: fairy tales, mysticism, alchemy, subconsciousness, psyche Słowa kluczowe: bajki, mistyka, alchemia, podświadomość, psyche Victorian interest in alchemical science Nineteenth-century fantasy fiction derived its form from a different type of inspira- tion than modern fantasy fiction. As Michel Foucault accurately noted, regarding Flaubert’s imagination, nineteenth-century fantasy was more erudite than imagina- tive: “This domain of phantasms is no longer the night, the sleep of reason, or the uncertain void that stands before desire, but, on the contrary, wakefulness, untir- ing attention, zealous erudition, and constant vigilance.”1 Although, as we will see, Victorian fairy tales originate in the subconsciousness, the inspiration for symbolic 1 M. Foucault, Fantasia of the Library, [in:] Language, Counter-Memory, Practice: Selected Essays and Interviews, D.F. -

Verse and Transmutation History of Science and Medicine Library

Verse and Transmutation History of Science and Medicine Library VOLUME 42 Medieval and Early Modern Science Editors J.M.M.H. Thijssen, Radboud University Nijmegen C.H. Lüthy, Radboud University Nijmegen Editorial Consultants Joël Biard, University of Tours Simo Knuuttila, University of Helsinki Jürgen Renn, Max-Planck-Institute for the History of Science Theo Verbeek, University of Utrecht VOLUME 21 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.com/hsml Verse and Transmutation A Corpus of Middle English Alchemical Poetry (Critical Editions and Studies) By Anke Timmermann LEIDEN • BOSTON 2013 On the cover: Oswald Croll, La Royalle Chymie (Lyons: Pierre Drobet, 1627). Title page (detail). Roy G. Neville Historical Chemical Library, Chemical Heritage Foundation. Photo by James R. Voelkel. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Timmermann, Anke. Verse and transmutation : a corpus of Middle English alchemical poetry (critical editions and studies) / by Anke Timmermann. pages cm. – (History of Science and Medicine Library ; Volume 42) (Medieval and Early Modern Science ; Volume 21) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-90-04-25484-8 (hardback : acid-free paper) – ISBN 978-90-04-25483-1 (e-book) 1. Alchemy–Sources. 2. Manuscripts, English (Middle) I. Title. QD26.T63 2013 540.1'12–dc23 2013027820 This publication has been typeset in the multilingual “Brill” typeface. With over 5,100 characters covering Latin, IPA, Greek, and Cyrillic, this typeface is especially suitable for use in the humanities. For more information, please see www.brill.com/brill-typeface. ISSN 1872-0684 ISBN 978-90-04-25484-8 (hardback) ISBN 978-90-04-25483-1 (e-book) Copyright 2013 by Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, The Netherlands. -

The Philosopher's Stone

The Philosopher’s Stone Dennis William Hauck, Ph.D., FRC Dennis William Hauck is the Project Curator of the new Alchemy Museum, to be built at Rosicrucian Park in San Jose, California. He is an author and alchemist working to facilitate personal and planetary transformation through the application of the ancient principles of alchemy. Frater Hauck has translated a number of important alchemy manuscripts dating back to the fourteenth century and has published dozens of books on the subject. He is the founder of the International Alchemy Conference (AlchemyConference.com), an instructor in alchemy (AlchemyStudy.com), and is president of the International Alchemy Guild (AlchemyGuild. org). His websites are AlchemyLab.com and DWHauck.com. Frater Hauck was a presenter at the “Hidden in Plain Sight” esoteric conference held at Rosicrucian Park. His paper based on that presentation entitled “Materia Prima: The Nature of the First Matter in the Esoteric and Scientific Traditions” can be found in Volume 8 of the Rose+Croix Journal - http://rosecroixjournal.org/issues/2011/articles/vol8_72_88_hauck.pdf. he Philosopher’s Stone was the base metal into incorruptible gold, it could key to success in alchemy and similarly transform humans from mortal Thad many uses. Not only could (corruptible) beings into immortal (incor- it instantly transmute any metal into ruptible) beings. gold, but it was the alkahest or universal However, it is important to remember solvent, which dissolved every substance that the Stone was not just a philosophical immersed in it and immediately extracted possibility or symbol to alchemists. Both its Quintessence or active essence. The Eastern and Western alchemists believed it Stone was also used in the preparation was a tangible physical object they could of the Grand Elixir and aurum potabile create in their laboratories. -

THE PHILOSOPHERS STONE by Israel Regardie

THE PHILOSOPHERS STONE By Israel Regardie CONTENTS I. Introduction BOOK ONE Chapter II. The Golden Treatise of Hermes III. Commentary IV. Commentary (continued) BOOK TWO V. The Magnetic Theory VI. The Six Keys of Eudoxus VII. Commentary VIII. The Magical view BOOK THREE IX. Coelum Terrae by Thomas Vaughan Conclusion Israel Regardie - The Philosophers Stone BOOK ONE CHAPTER ONE INTRODUCTION The word Alchemy is an Arabic term consisting of the article al and the noun khemi. We may take it that the noun refers to Egypt, whose Coptic name is Khem. The word, then, would yield the phrase “the Egyptian matter”, or “that which appertains to Egypt”. The hypothesis is that the Mohammedan grammarians held that the alchemical art was derived from that wisdom of the Egyptians which was the proud boast of Moses, Plato, and Pythagoras, and the source, therefore, of their illuminations. If, however, we assume the word to be of Greek origin, as do some authorities, then it implies nothing more than the chemical art, the method of mingling and making infusions. Originally all that chemistry meant was the art of extracting juices from plants and herbs. Modern scholarship still leaves unsolved the question as to whether alchemical treatises should be classified as mystical, magical, or simply primitively chemical. The most reasonable view is, in my opinion, not to place them exclusively in any one category, but to assume that all these objects at one time formed in varying proportions the preoccupation of different alchemists. Or, better still, that different alchemists became attracted to different interpretations or levels of the art. -

A Lexicon of Alchemy

A Lexicon of Alchemy by Martin Rulandus the Elder Translated by Arthur E. Waite John M. Watkins London 1893 / 1964 (250 Copies) A Lexicon of Alchemy or Alchemical Dictionary Containing a full and plain explanation of all obscure words, Hermetic subjects, and arcane phrases of Paracelsus. by Martin Rulandus Philosopher, Doctor, and Private Physician to the August Person of the Emperor. [With the Privilege of His majesty the Emperor for the space of ten years] By the care and expense of Zachariah Palthenus, Bookseller, in the Free Republic of Frankfurt. 1612 PREFACE To the Most Reverend and Most Serene Prince and Lord, The Lord Henry JULIUS, Bishop of Halberstadt, Duke of Brunswick, and Burgrave of Luna; His Lordship’s mos devout and humble servant wishes Health and Peace. In the deep considerations of the Hermetic and Paracelsian writings, that has well-nigh come to pass which of old overtook the Sons of Shem at the building of the Tower of Babel. For these, carried away by vainglory, with audacious foolhardiness to rear up a vast pile into heaven, so to secure unto themselves an immortal name, but, disordered by a confusion and multiplicity of barbarous tongues, were ingloriously forced. In like manner, the searchers of Hermetic works, deterred by the obscurity of the terms which are met with in so many places, and by the difficulty of interpreting the hieroglyphs, hold the most noble art in contempt; while others, desiring to penetrate by main force into the mysteries of the terms and subjects, endeavour to tear away the concealed truth from the folds of its coverings, but bestow all their trouble in vain, and have only the reward of the children of Shem for their incredible pain and labour. -

Alchemy Ancient and Modern

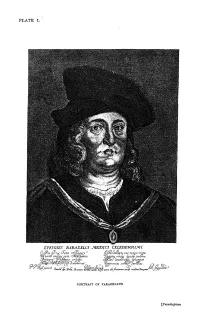

PLATE I. EFFIGIES HlPJ^SELCr JWEDlCI PORTRAIT OF PARACELSUS [Frontispiece ALCHEMY : ANCIENT AND MODERN BEING A BRIEF ACCOUNT OF THE ALCHEMISTIC DOC- TRINES, AND THEIR RELATIONS, TO MYSTICISM ON THE ONE HAND, AND TO RECENT DISCOVERIES IN HAND TOGETHER PHYSICAL SCIENCE ON THE OTHER ; WITH SOME PARTICULARS REGARDING THE LIVES AND TEACHINGS OF THE MOST NOTED ALCHEMISTS BY H. STANLEY REDGROVE, B.Sc. (Lond.), F.C.S. AUTHOR OF "ON THE CALCULATION OF THERMO-CHEMICAL CONSTANTS," " MATTER, SPIRIT AND THE COSMOS," ETC, WITH 16 FULL-PAGE ILLUSTRATIONS SECOND AND REVISED EDITION LONDON WILLIAM RIDER & SON, LTD. 8 PATERNOSTER ROW, E.G. 4 1922 First published . IQH Second Edition . , . 1922 PREFACE TO THE SECOND EDITION IT is exceedingly gratifying to me that a second edition of this book should be called for. But still more welcome is the change in the attitude of the educated world towards the old-time alchemists and their theories which has taken place during the past few years. The theory of the origin of Alchemy put forward in I has led to considerable discussion but Chapter ; whilst this theory has met with general acceptance, some of its earlier critics took it as implying far more than is actually the case* As a result of further research my conviction of its truth has become more fully confirmed, and in my recent work entitled " Bygone Beliefs (Rider, 1920), under the title of The Quest of the Philosophers Stone," I have found it possible to adduce further evidence in this connec tion. At the same time, whilst I became increasingly convinced that the main alchemistic hypotheses were drawn from the domain of mystical theology and applied to physics and chemistry by way of analogy, it also became evident to me that the crude physiology of bygone ages and remnants of the old phallic faith formed a further and subsidiary source of alchemistic theory. -

The Poetics of Science: Intertextual and Metatextual Themes in Ovid's Depiction of Cosmic and Human Origins

Provided by the author(s) and NUI Galway in accordance with publisher policies. Please cite the published version when available. Title The poetics of science: intertextual and metatextual themes in Ovid's depiction of cosmic and human origins Author(s) Kelly, Peter Publication Date 2016-09-09 Item record http://hdl.handle.net/10379/6075 Downloaded 2021-09-28T20:42:11Z Some rights reserved. For more information, please see the item record link above. The Poetics of Science Intertextual and Metatextual Themes in Ovid’s Depiction of Cosmic and Human Origins By Peter M. J. Kelly A Thesis Submitted to the National University of Ireland, Galway in the College of Arts, Social Sciences and Celtic Studies for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Classics September 2016 Supervisor: Prof. Michael Clarke ii Preface This work explores ancient views of cosmogony and the material structure of the universe in Ovid’s Metamorphoses. In particular it focuses on the way in which Ovid problematizes how we define myth and poetry versus science and philosophy. It examines how Ovid generates a parallel between the form and content of the text in order to depict a world where abstract scientific principles can become personified deities. This work will seek to reevaluate the impact of Greek Philosophy on Roman poetry through extending the series of intertexts which we may observe Ovid alluding to. Through following and analysing these sets of allusions this work will seek to gain an insight into Ovid’s depiction of the metatextual universe. iii iv For my Parents The scientist’s demand that nature shall be lawful is a demand for unity. -

Agrippa's Cosmic Ladder: Building a World with Words in the De Occulta Philosophia

chapter 4 Agrippa’s Cosmic Ladder: Building a World with Words in the De Occulta Philosophia Noel Putnik In this essay I examine certain aspects of Cornelius Agrippa’s De occulta philosophia libri tres (Three Books of Occult Philosophy, 1533), one of the foun- dational works in the history of western esotericism.1 To venture on a brief examination of such a highly complex work certainly exceeds the limitations of an essay, but the problem I intend to delineate, I believe, can be captured and glimpsed in its main contours. I wish to consider the ways in which the German humanist constructs and represents a common Renaissance image of the universe in his De occulta philosophia. This image is of pivotal importance for understanding Agrippa’s peculiar worldview as it provides a conceptual framework in which he develops his multilayered and heterodox thought. In other words, I deal with Agrippa’s cosmology in the context of his magical the- ory. The main conclusion of my analysis is that Agrippa’s approach to this topic is remarkably non-visual and that his symbolism is largely of verbal nature, revealing an author predominantly concerned with the nature of discursive language and the linguistic implications of magical thinking. The De occulta philosophia is the largest, most important, and most complex among the works of Heinrich Cornelius Agrippa von Nettesheim (1486–1535). It is a summa of practically all the esoteric doctrines and magical practices ac- cessible to the author. As is well known and discussed in scholarship, this vast and diverse amount of material is organized within a tripartite structure that corresponds to the common Neoplatonic notion of a cosmic hierarchy. -

Remarks Upon Alchemy and the Alchemists

Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2010 with funding from Research Library, The Getty Research Institute http://www.archive.org/details/remarksuponalcheOOhitc NEW THOUGTIT LIBRARY ASSOCIATION' No. REMARKS ALCHEMY AND THE ALCHEMISTS, INDICATIXG A METHOD OF DISCOVEKI^'G THE TEUE NATURE OF HERMETIC PHILOSOPHY; A^D SHOWING THAT THE SEARCH AFTER HAD NOT FOR ITS OBJECT THE DISCOVERY OF AN AGENT FOR THE TRANSMUTATION OF METALS. BEING ALSO AS ATTEMPT TO RESCUE FROM UNDESERVED OPPROBRIUM THE REPUTATION OF A CLASS OF EXTEAORDIXARY THINKEES IN PAST AGES. ' Man shall not live by bread alone." BOSTON: CROSBY, NICHOLS, AND COMPANY, 111 Washington Street. 1857. Entered according to Act of Congress, in the year 1857, by Crosby, Nichols, and Company, in the Clerk's Office of the District Court of the District of Massachusetts. cambsidge: metcalf and company, printers to the tjnrversitt. NE¥/ THOUGHT LIBRARY ASSOCIATION No. PEEFACE. ED.W. PARKER, L ittle Ruc k, Ark. It may seem superfluous in the author of the fol- lowing remarks to disclaim the purpose of re vivino- the study of Alchemy, or the method of teaching adopted by the Alchemists. Alchemical works stand related to moral and intellectual geography, some- what as the skeletons of ichthyosauri and plesio- sauri are related to geology. They are skeletons of thought in past ages. It is chiefly from this point of view that the writer of the following pages submits his opinions upon Alchemy to the public. He is convinced that the character of the Alchemists, and the object of their study, have been almost universally misconceived ; and as a matter of fact^ though of the past, he thinks it of sufficient importance to take a step in the right direction for developing the true nature of the studies of that extraordinary class of thinkers. -

Gold and Silver: Perfection of Metals in Medieval and Early Modern Alchemy Citation: F

Firenze University Press www.fupress.com/substantia Gold and silver: perfection of metals in medieval and early modern alchemy Citation: F. Abbri (2019) Gold and sil- ver: perfection of metals in medieval and early modern alchemy. Substantia 3(1) Suppl.: 39-44. doi: 10.13128/Sub- Ferdinando Abbri stantia-603 DSFUCI –Università di Siena, viale L. Cittadini 33, Il Pionta, Arezzo, Italy Copyright: © 2019 F. Abbri. This is E-mail: [email protected] an open access, peer-reviewed article published by Firenze University Press (http://www.fupress.com/substantia) Abstract. For a long time alchemy has been considered a sort of intellectual and histo- and distributed under the terms of the riographical enigma, a locus classicus of the debates and controversies on the origin of Creative Commons Attribution License, modern chemistry. The present historiography of science has produced new approach- which permits unrestricted use, distri- es to the history of alchemy, and the alchemists’ roles have been clarified as regards the bution, and reproduction in any medi- vicissitudes of Western and Eastern cultures. The paper aims at presenting a synthetic um, provided the original author and profile of the Western alchemy. The focus is on the question of the transmutation of source are credited. metals, and the relationships among alchemists, chymists and artisans (goldsmiths, sil- Data Availability Statement: All rel- versmiths) are stressed. One wants to emphasise the specificity of the history of alche- evant data are within the paper and its my, without any priority concern about the origins of chemistry. Supporting Information files. Keywords. History of alchemy, precious metals, transmutation of metals. -

![PETRUS BONUS, Pretiosa Margarita Novella [The Precious New Pearl] in Latin, Decorated Manuscript on Paper Spain (Catalonia), C](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9704/petrus-bonus-pretiosa-margarita-novella-the-precious-new-pearl-in-latin-decorated-manuscript-on-paper-spain-catalonia-c-879704.webp)

PETRUS BONUS, Pretiosa Margarita Novella [The Precious New Pearl] in Latin, Decorated Manuscript on Paper Spain (Catalonia), C

PETRUS BONUS, Pretiosa margarita novella [The Precious New Pearl] In Latin, decorated manuscript on paper Spain (Catalonia), c. 1450-1480 i (paper) + 92 + i (paper) folios on paper (watermarks, unidentified Oxhead, and Oxhead with eyes, nostrils, further features, above a crescent moon, similar to Briquet 14390, Montpellier 1458, Montpellier 1449-1466, and Clermont Ferrand 1460, and WIES, IBE 4435.02, Tortosa 1477), early foliation in faded ink, top outer corner recto, 1- 30, with f. 10 bis, modern foliation in pencil, top outer corner recto (cited), complete (collation, i-vii12 viii12 [-9 through 12, cancelled with no loss of text]), horizontal catchwords inner lower margin, no signatures, ruled very lightly in lead, with full length vertical bounding lines and with the top and bottom horizontal rules full across on a few folios (justification, 205-203 x 144-140 mm.), written below the top line in a stylized cursive gothic bookhand with no loops in two columns of thirty-eight lines, red rubrics, alternately red and blue paragraph marks and two-line initials, large three-line initial, f. 1, darkened silver (?) on a notched ground that follows the shape of the initial (color damaged, yellow?) with a short spray of leaves and small flowers with black ink sprays extending from the initial into the inner margin, trimmed, with loss of some marginalia, f. 73, large hole in the top inner portion of the leaf (loss of text), f. 24, small hole top margin, f. 1, initial damaged, water stains upper margins and top lines of text, (text remains legible, with some passages rewritten in darker ink), smaller, darker stains lower margins, but in sound and legible condition.