Island Narrations, Imperial Dramas and Vieques, Puerto Rico

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

European Athletics Outdoor 10.2016

EUROPEAN ATHLETICS OUTDOOR 10.2016 AUSTRIA Linz (Austria), 29.6.2016 Men PV 1 Michal Balner (cze) 5.66; 2 Luke Cutts (gbr) 5.61; 3 Hendrik Gruber (ger) 5.51; 4 Marvin Caspari (ger) 5.41; 5 Torben Laidig (ger) 5.31; 6 Tom Konrad (ger) 5.31; 7 Emmanouil Karalis (gre) (99) 5.31 Women PV 1 Tina Sutej (slo) 4.56; 2 Nastja Modic (slo) 4.21; 3 Aneta Morysková (cze) 4.21; 4 Sarah Zimmer 4.06; 5 Agnes Hodi (hun) 4.06 BELGIUM Lokeren (Belgium), 3.7.2016 Men 100m h1 (-0,5) 1 Stanly del Carmen (dom) 10.39; 2 Deji Tobais (gbr) 10.49; 3 Walter Ungerer (rsa) 10.55; h2 (-0,2) Christopher Valdez (dom) 10.52 200m h1 (-0,2) 1 Stanly Del Carmen (dom) 20.73; 2 Patrick Van Luijk (ned) 20.99; 3 Yohandri Andújar (dom) 21.12; 4 Gustavo Cuesta (dom) 21.46; 200m h2 (-0,3) 1 Walter Ungerer (rsa) 21.19; 2 Deji Tobais (gbr) 21.44 400m h1 1 Juander Santos (dom) 46.38; 2 Terrence Agard (ned) 46.94; 3 Yon Soriano (dom) 46.95; 4 Denis Opio (uga) 47.40; h2 1 Jurgen Wielart (ned) 46.40; 3 Luis Charles (dom) 47.11; 3 Seppe Thys 47.27; 4 Rodwell Ndlovu (zim) 47.60; 5 Lacarl Hayes (ngr) 47.93; h3 1 Obed Martis (ned) 47.30; 2 Alexander Doom 47.61; 3 Samba Fall (sen) 47.75; 4 Timmy Crowe (irl) 47.83; h4 1 Florian Weeke (ger) 47.36; 2 Olaf van den Bergh (ned) 47.67 800m h1 1 Jamal Hairane (qat) 1.46.47; 2 Isaac Kimeli 1.47.52; 3 Patrick Zwicker (ger) 1.47.59; 4 Jared West (aus) 1.47.64; 5 Alex Rowe (aus) 1.47.75; 6 Koudi Babker (sud) 1.47.89; 7 Lucirio Garrido (ven) 1.48.01; 8 Luis Alberto Marco (esp) 1.49.57; h2 1 James Eichberger (mex) 1.48.40; 2 Pieter Claus 1.48.46; 3 David -

Cancel Culture: Posthuman Hauntologies in Digital Rhetoric and the Latent Values of Virtual Community Networks

CANCEL CULTURE: POSTHUMAN HAUNTOLOGIES IN DIGITAL RHETORIC AND THE LATENT VALUES OF VIRTUAL COMMUNITY NETWORKS By Austin Michael Hooks Heather Palmer Rik Hunter Associate Professor of English Associate Professor of English (Chair) (Committee Member) Matthew Guy Associate Professor of English (Committee Member) CANCEL CULTURE: POSTHUMAN HAUNTOLOGIES IN DIGITAL RHETORIC AND THE LATENT VALUES OF VIRTUAL COMMUNITY NETWORKS By Austin Michael Hooks A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the University of Tennessee at Chattanooga in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements of the Degree of Master of English The University of Tennessee at Chattanooga Chattanooga, Tennessee August 2020 ii Copyright © 2020 By Austin Michael Hooks All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT This study explores how modern epideictic practices enact latent community values by analyzing modern call-out culture, a form of public shaming that aims to hold individuals responsible for perceived politically incorrect behavior via social media, and cancel culture, a boycott of such behavior and a variant of call-out culture. As a result, this thesis is mainly concerned with the capacity of words, iterated within the archive of social media, to haunt us— both culturally and informatically. Through hauntology, this study hopes to understand a modern discourse community that is bound by an epideictic framework that specializes in the deconstruction of the individual’s ethos via the constant demonization and incitement of past, current, and possible social media expressions. The primary goal of this study is to understand how these practices function within a capitalistic framework and mirror the performativity of capital by reducing affective human interactions to that of a transaction. -

1.3. El Ruido De Ocio Nocturno 3

UNIVERSIDAD POLITÉCNICA DE MADRID Escuela Técnica Superior de Ingeniería Y Sistemas de Telecomunicación TRABAJO FIN DE MÁSTER MÁSTER UNIVERSITARIO EN INGENIERÍA ACÚSTICA DE LA EDIFICACIÓN Y MEDIO AMBIENTE TRATAMIENTO Y ANALISIS DEL OCIO NOCTURNO EN LAS CIUDADES JULEN ECHARTE PUY Julio de 2019 Máster en Ingeniería Acústica de la Edificación y Medio Ambiente Trabajo Fin de Máster Título Autor VºBº Tutor Ponente Tribunal Presidente Secretario Vocal Fecha de lectura Calificación El Secretario: Índice Índice i Índice de ilustraciones iii Índice de graficas v Resumen vii Summary ix 1 Introducción 1 1.1. Introducción 2 1.2. El ruido y la contaminación acústica 2 1.3. El ruido de ocio nocturno 3 1.4. Legislación en materia de ruido 4 2 Gestión del ruido en la ciudad de Madrid 5 2.1. Madrid como ejemplo de lucha contra el ruido de ocio nocturno 6 2.2. ZAP (Zona Ambientalmente Protegida) 6 2.2.1. ZAP Chamberí 7 2.2.2. ZAP Vicálvaro 11 2.2.3. ZAP Chamartín 12 2.2.4. ZAP Salamanca 14 2.3. ZPAE, Zona de Protección Acústica Especial. 17 2.3.1. ZPAE de Aurrera 17 2.3.2. ZPAE Distrito de Centro 25 i 2.3.3. ZPAE Avenida Azca – Avenida de Brasil 30 2.3.4. ZPAE Barrio de Gaztambide 36 2.3.5. ZPAE Distrito de Centro 2018 46 2.3.6. Conclusiones del análisis de las ZPAE de la Ciudad de Madrid. 56 3 Gestión del ruido en otras ciudades 57 3.1. Introducción 58 3.2. Málaga 58 3.3. Murcia 64 3.4. -

UNIVERSIDAD DE PUERTO RICO RECINTO DE RÍO PIEDRAS SISTEMA DE BIBLIOTECAS CÓDIGO DE REFERENCIA: PR UPR-RP CPR Policía De Puert

UNIVERSIDAD DE PUERTO RICO RECINTO DE RÍO PIEDRAS SISTEMA DE BIBLIOTECAS CÓDIGO DE REFERENCIA: PR UPR-RP CPR Policía de Puerto Rico TÍTULO : Carpeta de Julio Antonio Muriente Pérez FECHA(S): 1968 febrero –1984 julio NIVEL DE DESCRIPCIÓN: Subserie VOLUMEN Y SOPORTE DE LA UNIDAD DE DESCRIPCIÓN (CANTIDAD O DIMENSIÓN): 7 carpetas, enumeradas las hojas con la enumeración 000001-002150. NOMBRE DEL O DE LOS PRODUCTORES : Policía de Puerto Rico. División de Inteligencia. HISTORIA INSTITUCIONAL: Policía de Puerto Rico La Orden General Núm. 195 del 29 de noviembre de 1899 es expedida por el ayudante del Gobernador General Guy V. Henry, establece las Cortes de Policía. Dicha Orden otorga poderes ilimitados. La segunda Orden General, Núm. 15 de 9 de febrero de 1899 en su sección IV indica la creación de un departamento de Policía cuyo jefe estará sujeto a las órdenes directas del Gobernador General. Con este documento se establece oficialmente el Cuerpo de la Policía Insular de Puerto Rico, como se llamó hasta el 1 1956. Surgen otras reorganizaciones en la Policía, el 31 de enero de 1901 y con la Ley 33 del 8 de junio de1948. Al presente la Policía de Puerto Rico es un organismo civil dirigido por un superintendente, quien es nombrado por el Gobernador con el consentimiento del Senado. Todo el personal de la Policía es nombrado por el superintendente de acuerdo con el Reglamento, mientras que los nombramientos de coroneles, tenientes coroneles y comandantes están sujetos a la aprobación del Gobernador. DIVISIÓN DE INVESTIGACIONES En 1908 se reorganiza la Policía Insular de Puerto Rico mediante proyecto de Ley, presentado a la Legislatura por Luis Muñoz Rivera y convertido en Ley por el Gobernador. -

START LIST 4 X 400 Metres Relay Mixed - Round 1 First 2 in Each Heat (Q) and the Next 2 Fastest (Q) Advance to the Final

Cali (COL) World Youth Championships 15-19 July 2015 START LIST 4 x 400 Metres Relay Mixed - Round 1 First 2 in each heat (Q) and the next 2 fastest (q) advance to the Final i = Indoor performance Heat 1 3 18 July 2015 11:45 START TIME LANE TEAM BIB NATIONAL RECORD SEASON BEST 2 ITALY ITA 1 1281 Rebecca BORGA (G) 2 1293 Linda OLIVIERI (G) 3 344 Andrea ROMANI (B) 4 330 Vladimir ACETI (B) 3 PR OF CHINA CHN 1 1086 Jiaxin HUANG (G) 2 1088 Nuo LIANG (G) 3 112 Yuang WU (B) 4 114 Haoran XU (B) 4 NORWAY NOR 1 465 Mathias Hove JOHANSEN (B) 2 466 Toralv OPSAL (B) 3 1394 Kristine Berger AKERVOLD (G) 4 1395 Mari DRABLØS (G) 5 POLAND POL 1 653 Natan FIEDEN (B) 2 1422 Natalia KACZMAREK (G) 3 1574 Katarzyna MARTYNA (G) 4 490 Tymoteusz ZIMNY (B) 6 COLOMBIA COL 1 129 Rodrigo Alberto LAGARES (B) 2 1120 Marisofía PINILLA (G) 3 1114 Jarly Camila MARÍN (G) 4 140 Anthony José ZAMBRANO (B) 7 UZBEKISTAN UZB 1 1573 Anjelika BELOVA (G) 2 1575 Elmira GAZIZOVA (G) 3 638 Shokhrukh BARATOV (B) 4 639 Jaloliddin KHAMROKULOV (B) 8 GERMANY GER 1 265 Florian COLON MARTI (B) 2 277 Marvin SCHLEGEL (B) 3 1233 Jana REINERT (G) 4 1239 Corinna SCHWAB (G) 1 Timing and Measurement by SEIKO Data Processing by CANON AT-4X4-X-h----.SL2..v2 Issued at 11:54 on Saturday, 18 July 2015 3 Official IAAF Partners Cali (COL) World Youth Championships 15-19 July 2015 START LIST 4 x 400 Metres Relay Mixed - Round 1 Heat 2 3 18 July 2015 11:55 START TIME LANE TEAM BIB NATIONAL RECORD SEASON BEST 2 GREECE GRE 1 1248 Ánna KIÁFA (G) 2 283 Yeóryios KALOYERÁKIS (B) 3 1252 Alexía POLIKRÁTI (G) 4 291 -

Sankofaspirit

SankofaSpirit Looking Back to Move Forward (770) 234-5890 ▪ www.sankofaspirit.com P.O Box 54894 ▪ Atlanta, Georgia 30308 Movies with a Mission 2009 Season The APEX Museum, 135 Auburn Avenue, Atlanta Gallery Walk, Screening and Dialogue Schedule Subject to Change Season Premiere, Saturday, February 7, 6:00-8:00pm “Traces of the Trade: A Story From the Deep North” A unique and disturbing journey of discovery into the history and "living consequences" of one of the United States' most shameful episodes — slavery. In this bicentennial year of the U.S. abolition of the slave trade, one might think the tragedy of African slavery in the Americas has been exhaustively told. Katrina Browne thought the same, until she discovered that her slave-trading ancestors from Rhode Island were not an aberration. Rather, they were just the most prominent actors in the North's vast complicity in slavery, buried in myths of Northern innocence. Browne — a direct descendant of Mark Anthony DeWolf, the first slaver in the family — took the unusual step of writing to 200 descendants, inviting them to journey with her from Rhode Island to Ghana to Cuba and back, recapitulating the Triangle Trade that made the DeWolfs the largest slave-trading family in U.S. history. Nine relatives signed up. Traces of the Trade: A Story from the Deep North is Browne's spellbinding account of the journey that resulted. Thursday, March 5, 6:00-8:00pm “500 Years Later” Beautifully filmed with compelling discussions with the world's leading scholars, 500 Years Later explores the collective atrocities that uprooted Africans from their culture and homeland, and scattered them into the vehement winds of the New World, 500 years ago. -

San Juan, Puerto Rico Via East Orange, New Jersey, Making It Work: Cultural Resource Management from Across an Ocean

SAN JUAN, PUERTO RICO VIA EAST ORANGE, NEW JERSEY, MAKING IT WORK: CULTURAL RESOURCE MANAGEMENT FROM ACROSS AN OCEAN Timothy R. Sara and Sharla C. Azizi The Louis Berger Group, Inc. ❐ ABSTRACT This paper describes the principal findings of an urban archaeological investigation conducted in a cultural resource management (CRM) context in Old San Juan, Puerto Rico (Sara and Marín Rom n 1999). The inves- tigation was prompted by the United States General Services Administration’s need to rehabilitate the Federal Courthouse and Post Office Building in the Old City. A major component of the investigation was the recovery and analysis of more than 16,000 Spanish colonial-period artifacts from urban fills beneath the building. The col- lection includes a total of 106 ceramic ware types, various small finds including gun flints, tobacco pipes, bone combs, die, and buttons, dietary faunal remains, and fine examples of European decorated glass. Analysis of these artifacts revealed that, despite strict trade laws imposed by the Spanish Crown, San Juan was well-integrated in the world economy early in its history. As a result of careful planning and coordination by project archaeologists and engineers, the remains of the Bastión de San Justo del Muelle, a massive seventeenth-century fortification work, was left in situ beneath the building during new construction. The successful outcome of the project was owed to the close coordination by the Federal and local government agencies, historic preservation consultants, and local specialists in Puerto Rican history and historical archaeology. Resumen Esta ponencia describir una programa de investigación arqueológica manejar en un contexto de Manejo de Recursos Culturales en el Viejo San de Puerto Rico (Sara y Marín Rom n 1999). -

Puerto Rico, Colonialism In

University at Albany, State University of New York Scholars Archive Latin American, Caribbean, and U.S. Latino Latin American, Caribbean, and U.S. Latino Studies Faculty Scholarship Studies 2005 Puerto Rico, Colonialism In Pedro Caban University at Albany, State Univeristy of New York, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.library.albany.edu/lacs_fac_scholar Part of the Latin American Studies Commons Recommended Citation Caban, Pedro, "Puerto Rico, Colonialism In" (2005). Latin American, Caribbean, and U.S. Latino Studies Faculty Scholarship. 19. https://scholarsarchive.library.albany.edu/lacs_fac_scholar/19 This Encyclopedia Entry is brought to you for free and open access by the Latin American, Caribbean, and U.S. Latino Studies at Scholars Archive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Latin American, Caribbean, and U.S. Latino Studies Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of Scholars Archive. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 516 PUERTO RICO, COLONIALISM IN PUERTO RICO, COLONIALISM IN. Puerto Rico They automatically became subjects of the United States has been a colonial possession of the United States since without any constitutionally protected rights. Despite the 1898. What makes Puerto Rico a colony? The simple an humiliation of being denied any involvement in fateful swer is that its people lack sovereignty and are denied the decisions in Paris, most Puerto Ricans welcomed U.S. fundamental right to freely govern themselves. The U.S. sovereignty, believing that under the presumed enlight Congress exercises unrestricted and unilateral powers over ened tutelage of the United States their long history of Puerto Rico, although the residents of Puerto Rico do not colonial rule would soon come to an end. -

Cyperaceae of Puerto Rico. Arturo Gonzalez-Mas Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1964 Cyperaceae of Puerto Rico. Arturo Gonzalez-mas Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Gonzalez-mas, Arturo, "Cyperaceae of Puerto Rico." (1964). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 912. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/912 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This dissertation has been 64—8802 microfilmed exactly as received GONZALEZ—MAS, Arturo, 1923- CYPERACEAE OF PUERTO RICO. Louisiana State University, Ph.D., 1964 B o ta n y University Microfilms, Inc., Ann Arbor, Michigan CYPERACEAE OF PUERTO RICO A Dissertation I' Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of Botany and Plant Pathology by Arturo Gonzalez-Mas B.S., University of Puerto Rico, 1945 M.S., North Carolina State College, 1952 January, 1964 PLEASE NOTE: Not original copy. Small and unreadable print on some maps. Filmed as received. UNIVERSITY MICROFILMS, INC. ACKNOWLEDGMENT The author wishes to express his sincere gratitude to Dr. Clair A. Brown for his interest, guidance, and encouragement during the course of this investigation and for his helpful criticism in the preparation of the manuscript and illustrations. -

Political Status of Puerto Rico: Options for Congress

Political Status of Puerto Rico: Options for Congress R. Sam Garrett Specialist in American National Government June 7, 2011 Congressional Research Service 7-5700 www.crs.gov RL32933 CRS Report for Congress Prepared for Members and Committees of Congress Political Status of Puerto Rico: Options for Congress Summary The United States acquired the islands of Puerto Rico in 1898 after the Spanish-American War. In 1950, Congress enacted legislation (P.L. 81-600) authorizing Puerto Rico to hold a constitutional convention and in 1952, the people of Puerto Rico ratified a constitution establishing a republican form of government for the island. After being approved by Congress and the President in July 1952 and thus given force under federal law (P.L. 82-447), the new constitution went into effect on July 25, 1952. Puerto Rico is subject to congressional jurisdiction under the Territorial Clause of the U.S. Constitution. Over the past century, Congress passed legislation governing Puerto Rico’s relationship with the United States. For example, residents of Puerto Rico hold U.S. citizenship, serve in the military, are subject to federal laws, and are represented in the House of Representatives by a Resident Commissioner elected to a four-year term. Although residents participate in the presidential nominating process, they do not vote in the general election. Puerto Ricans pay federal tax on income derived from sources in the mainland United States, but they pay no federal tax on income earned in Puerto Rico. The Resident Commissioner may vote in committees but is not permitted to vote in, or preside over, either the Committee of the Whole or th the House in the 112 Congress. -

Adnpr 20190224 153902 15

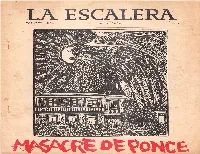

VOL . 11 J. MARZO DE 1969 MUM. 3 SUMARIO Notas Ed i t-or i a 1 es, .......................................................................... i La M asacre de Ponce Entrevista con el Lie,, Lorenzo Piñeíro 1 Documentos para la Historia de Puerto Rico . Reseña; Reflexiones de un sociólogo . latinoame ricano sobre el libro del. Prof0 Germán d e G r a n da e®®»®’©®.®©®®».®®..*©. .«.o©©®.®®».® 33 Tribunal Supremo U.S. y Tribunal Supremo P'.R. vs„ La Casa de Estudios ................... .... 3 8 . Diálogo con Nuestros Lectores .............................® . ®. „ ©.. I|.l| Portada; Grabado TiLa Masacre de Ponce." de Carlos Raquel Rivera| diseño de Rafael Rivera Rosa L A ___E S C ALERA Conseje-de Redacción Revista bimensual editada y publicada por "Publicaciones G erani sam ".. Gervasio L. García Las opiniones expresadas en los artículos son las de los Georg Fromm - RicHard Levins colaboradores y no necesaria mente la s de LA ESCALERA. Leroy Robinson - Juan Fiestas Se permite la reproducción p a r ó ia l o t o t a l de lo s a r t í c u Samuel Aponte los originales para LA ESCALERA, siempre que se indique su pro cedencia® Distribución: Juan Mestas 1 Toda correspondencia debe d iri y Julio Rivera ¡ g ir s e a: "Publicaciones Geranisam" Apartado 22776, Estación U.P.R. Suscripción anual: $2® 00 Río Piedras, Puerto Rico 00931 NOTAS EDITORIALES Aparece, de nuevo.La Escalera, luego de un largo silencio debido principalmente a la falta de recursos humanos. .Por diversas circunstan cias ( viajes de estudio, emigración en búsqueda de empleos, etc. ), el equipo de trabajo con que contábamos fue reduciéndose hasta el punto en que no era ya posible seguir publicando la revista. -

Request for Proposals (Rfp) No: Bmic-Osiatd-Fy2017-001 Basic Maintenance of Internal Connections Equipment

REQUEST FOR PROPOSALS (RFP) NO: BMIC-OSIATD-FY2017-001 BASIC MAINTENANCE OF INTERNAL CONNECTIONS EQUIPMENT EVENT DATE/TIME* Publication and release of RFP Monday, May 1st 2017 Deadline for Submitting RFP Questions 10:00 a.m., Monday May 15, 2017 Pre-Proposal Vendor Conference (Optional**) 10:00 a.m., Friday May 19, 2017 Deadline for Submitting Letters of Intent (Mandatory) 12:00 p.m., Monday May 22, 2017 DEADLINE FOR SUBMITTING PROPOSALS 12:00 p.m., Monday June 5, 2017 * All listed times are Atlantic Standard Time (AST) **The Pre-Proposal Vendor Conference would be held at Corrections Building at the address below. LATE PROPOSALS WILL NOT BE ACCEPTED PROPOSALS SUBMITTED BY FAX OR EMAIL WILL NOT BE ACCEPTED VENDORS SHALL DELIVER SIX (6) COPIES OF PROPOSALS AS FOLLOWS: 1 Signed Original Proposal in a 3-Ring Binder, clearly marked as the Original 4 Exact Copies of the Original Proposal in 3-Ring Binders, without Financial Statements 1 Exact Copy of the Original Proposal on a Jump Drive, including Financial Statements ALL PROPOSALS MUST BE ADDRESSED AND HAND-DELIVERED BY VENDOR OR COURIER TO THE FOLLOWING ADDRESS BY THE DEADLINE: José L. Narváez Figueroa Director Ejecutivo III Puerto Rico Department of Education Corrections Building, 4th Floor Tte. César González, Esquina Kalaf Urb. Industrial Tres Monjitas Hato Rey, PR 00926 All vendor questions concerning the RFP and the competitive proposal process should be in writing and emailed to: [email protected] P.O. Box 190759, San Juan PR 00919 -0759 • Tel.: (787)773-2696 The Department of Education does not discriminate under any circumstance on the grounds of age, race, color, gender, birth, religion, veteran status, political ideals, sexual orientation, gender identity, social condition or background, physical or mental incapacity; or for being victim of aggression, harassment, or domestic violence.