Walks to the Paradise Garden, a Lowdown Southern

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

July 1, 2015–June 30, 2016 FY16: a LOOK BACK

Georgia Museum of Art Annual Report July 1, 2015–June 30, 2016 FY16: A LOOK BACK This fiscal year, running from July 1, 2015, a dramatic uptick in attendance during the to June 30, 2016, was, as usual, packed with course of the show. Heather Foster, an MFA activities at the Georgia Museum of Art. The student at UGA in painting and an intern in exhibition El Taller de Gráfica Popular: Vida y our education department, created a series of Arte kicked off our fiscal year, providing the Pokemon-inspired cards highlighting different inspiration for our summer Art Adventures objects in the exhibition. We also embarked programming in 2015 as well as lectures, upon our first Georgia Funder, using UGA’s films, family programs and much more. We crowd-funding platform to raise money for the engaged in large amounts of Spanish-language exhibition’s programming. Caroline Maddox, programming, and the community responded our director of development, left for a position positively. at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, and Laura Valeri, associate curator, for Georgetown In July, the Friends of the Georgia Museum University Press. of Art kicked off a three-month campaign to boost membership by 100 households. Through In November, we focused attention on three carefully crafted marketing emails and the first major gifts from the George and Helen Segal in a series of limited-edition mugs available only Foundation, devoting an entire exhibition to through membership, they did just that and them. Other major acquisitions included a more. painting by Frederick Carl Frieseke (due to the generosity of the Chu Family Foundation), one In August, with the beginning of the university’s by Anthony Van Dyck and studio (from Mr. -

The E.S.C. Quarterly

The E. S. C. Quarterly VOLUME 7, NO. 3-4 1949 SUMMER-FALL # Merchandising Set New Record in North Carolina Last Year, Retail and Wholesale; History of Development ** One of North Carolina's many fine and modern department stores (see inside cover) PUBLISHED BY Employment Security Commission of North Carolina jpttm^awm FROM RALEIGH, N. C. - B^Y L : ;sTy im PAGE 82 THE E. S. C. QUARTERLY Summer-fall, 1949 The E. S. C. Quarterly MERCHANDISING IN STATE (Formerly The U.C.C. Quarterly) Merchandising in North Carolina is big business. Both wholesale and retail trade has developed and Volume 7, Numbers 3-4 Summer-Fall, 1949 expanded in the State to keep pace with the ever Issued four times a year at Raleigh, N. C, by the growing demands of the State's citizenship for more and EMPLOYMENT SECURITY COMMISSION OF better merchandise. Retail trade exceeded $2,- NORTH CAROLINA 137,000,000 during the fiscal year ended last June 30, and the North Carolina Department of Revenue does Commissioner:-;: Mrs. Quentin Gregory, Halifax; Dr. Harry D. not claim that these figures tell the complete story. Wolf, Chapel Hill; R. Dave Hall, Belmont; Marion W. Heiss, Much trading does not go on the records. Greensboro; C. A. Fink, Spencer; Bruce E. Davis, Charlotte. But the retail trade produced through the 3% sales and use State Advisory Council: Dr. Thurman D. Kitchin, Wake For- tax more than $40,000,000 in taxes, which is the est, chairman; Mrs. Gaston A. Johnson, High Point; W. B. Horton, Yanceyville; C. P. Clark, Wilson; Dr. -

Ten Galleries Whose Founders Quit the Big City to Become Cultural

November 30, 2018 Ten Galleries Whose Founders Quit The Big City To Become Cultural Trailblazers in the Heartland by Laura van Straaten “I’m the Gagosian of Memphis now,” jokes Matt Ducklo whose gallery Tops recently expanded to a second space. Six years ago, he opened the first location in the basement of a printing and stained-glass factory — to get down there, it’s a treacherous spelunk through a junk-filled hallway. The newer location is tucked into a small park nearby. Of course, the foot traffic in Memphis doesn’t quite compare to the throngs of gallerygoers in Chelsea. “If five people show up on a Saturday, I’m happy,” admits Ducklo. After an MFA at Yale and almost a decadelong career in photography in New York, economic pressures forced Ducklo to reconsider his priorities, “I thought, My goal in life was not to live in New York City but to do creative things, he recalls. He headed home to Tennessee where he quickly discovered, as he puts its, “the joy and despair of having a gallery that is far from a major art capital.” Ducklo’s in good company. He is one of ten gallerists I’ve discovered over the last few years who renounced their big-city careers on the coasts to create new art spaces in their heartland hometowns, or, in one case, the small town where a spouse’s career is. I first met most of these gallerists at art fairs like those opening next week in Miami — including NADA, Untitled, Pulse, and others in New York and even internationally. -

Report to Donors 2019

Report to Donors 2019 Table of Contents Mission 2 Board of Trustees 3 Letter from the Director 4 Letter from the President 5 Exhibitions and Publications 6 Public, Educational, and Scholarly Programs 11 Family and School Programs 16 Museum and Research Services 17 Acquisitions 18 Statement of Financial Position 24 Donors 25 Mission he mission of the Morgan Library & Museum is to preserve, build, study, present, and interpret a collection T of extraordinary quality in order to stimulate enjoyment, excite the imagination, advance learning, and nurture creativity. A global institution focused on the European and American traditions, the Morgan houses one of the world’s foremost collections of manuscripts, rare books, music, drawings, and ancient and other works of art. These holdings, which represent the legacy of Pierpont Morgan and numerous later benefactors, comprise a unique and dynamic record of civilization as well as an incomparable repository of ideas and of the creative process. 2 the morgan library & museum Board of Trustees Lawrence R. Ricciardi Susanna Borghese ex officio President T. Kimball Brooker Colin B. Bailey Karen B. Cohen Barbara Dau Richard L. Menschel Flobelle Burden Davis life trustees Vice President Annette de la Renta William R. Acquavella Jerker M. Johansson Rodney B. Berens Clement C. Moore II Martha McGarry Miller Geoffrey K. Elliott Vice President John A. Morgan Marina Kellen French Patricia Morton Agnes Gund George L. K. Frelinghuysen Diane A. Nixon James R. Houghton Treasurer Gary W. Parr Lawrence Hughes Peter Pennoyer Herbert Kasper Thomas J. Reid Katharine J. Rayner Herbert L. Lucas Secretary Joshua W. Sommer Janine Luke Robert King Steel Charles F. -

Extravaganza

Curadoria / Curator 13 abril — 15 setembro 2019 Colecção / Collection Antonia Gaeta 13 April — 15 September 2019 Treger / Saint Silvestre EXTRAVAGANZA Agatha Wojciechowsky maioritariamente, por desenhos executados Alemanha / Germany, 1896 – 1986 a grafite ou lápis de cor sobre papel onde prevalecem cenários nos quais convivem Agatha Wojciechowsky viveu em Steinach figuras masculinas e femininas com animais de Saale até 1923, ano em que emigrou para identificáveis ou imaginários. As composições os Estados Unidos para desempenhar funções apresentam uma particularidade: a personagem na casa de um barão alemão. Lá viria a casar-se principal, normalmente em destaque pelo seu e a obter a cidadania. No início da década de posicionamento ou pelo tamanho que ocupa no 1950, Wojciechowsky desenvolveu os seus papel, manifesta uma soberania face à(s) outra(s) primeiros desenhos numa linguagem abstrata, personagem(ns) representada(s). no entanto, é possível destacar-se alguma figuração. O exercício do desenho está Little is known about the life of Albino Braz before relacionado com a sua condição de medium he was committed to the psychiatric hospital of espiritual na medida em que Wojciechowsky Juquéri (São Paulo), specialized in the treatment explica que o ato de desenhar não é consciente of schizophrenia, besides the fact that he was nem ditado pelas suas motivações mas algo of Italian descent. He began drawing after being que Zé realizado pelas diferentes entidades hospitalised. His work consists mainly of graphite que habitam o seu corpo. O seu trabalho pode or coloured pencil drawings on paper in which ser encontrado em várias coleções públicas, we find scenarios where masculine and feminine como no Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), no Art figures coexist with identifiable or imaginary Institute of Chicago e no Whitney Museum. -

VERNACULAR ART from the Gadsden Arts Center Permanent Collection

VERNACULAR ART from the Gadsden Arts Center Permanent Collection Leepa-Rattner Museum of Art February 21–May 15, 2016 Tarpon Springs, Florida VERNACULAR ART from the Gadsden Arts Center Permanent Collection Vernacular Art from the Gadsden Arts Center Permanent Collection Gadsden Arts Center 13 North Madison Street Quincy, Florida 32351 850.875.4866 www.gadsdenarts.org © Gadsden Arts, Inc. 2016 All rights are reserved. No portion of this catalog may be reproduced in any form by mechanical or electronic means (including photocopying, recording, or information storage and retrieval) without permission in writing from Gadsden Arts, Inc. Photography by Ed Babcock and Roger Raepple Edited by Charlotte Kelley Cover image: Thornton Dial Sr., Everything is under the Black Tree, n.d., paint on wood, 48 x 31.5 inches, Gadsden Arts Center Permanent Collection, 2009.1.2 1 VERNACULAR ART from the Gadsden Arts Center Permanent Collection ThornTon Dial Sr. arThUr Dial Table of Contents ThornTon Dial Jr. Essays The Creative Spirit .............................................................................................5–8 hawkinS BolDen Art as an Expression of Place ........................................................................ 9–12 richarD BUrnSiDe Works of Art in the Exhibition ...........................................................13 archie Byron Artist Biographies and Works alyne harriS Thornton Dial Sr. .......................................................................................... 14–17 Arthur Dial ..................................................................................................... -

Harvey, Bessie CV

210 eleventh avenue, ste 201 new york, ny 10001 t 212 226 3768 f 212 226 0155 CAVIN-MORRIS GALLERY e [email protected] www.cavinmorris.com BESSIE HARVEY !(born October 11, 1929 in Dallas, Georgia; died August 12, 1994) Born in Dallas, Georgia in 1929, Bessie Harvey's childhood was one of poverty and hardship. She grew up during the Great Depression, the seventh of thirteen children. She is oft quoted as saying "The story of my life would make Roots and The Color Purple look like a fairy tale. There was nothing. In the morning, you'd just get up, go looking for whatever you could find, and if you had one meal that day, then you'd made progress." Bessie attended school through the fourth grade, then went to work as a domestic. She married Charles Harvey at the age of fourteen, so she was no longer a economic burden to her family. Bessie stayed married to Harvey into her early twenties. They separated and she independently moved away, eventually settling in Alcoa, Tennessee with their five children. There she continued to work as a domestic and later married Cleve Jackson. Over the course of a twenty year marriage which ended in divorce, the !couple had six children. Always deeply religious and attuned to the essential spiritual nature of the world, Bessie sought expression for her experiences and beliefs. She recalled creating toys and dolls,"something out of nothing", as a child. As an adult, she would do the same to bring her visionary experiences into the physical world. -

Annual Report Fiscal Year 2017 American Folk Art Museum July 1, 2016–June 30, 2017

ANNUAL REPORT FISCAL YEAR 2017 AMERICAN FOLK ART MUSEUM JULY 1, 2016–JUNE 30, 2017 In FY17, the American Folk Art Museum received a grant from The Leir Charitable Foundations, in memory of Henry J. and Erna D. Leir, to digitize the museum’s collection in its entirety. All of the museum’s holdings, including textiles, artists’ books, paintings, photographs, and sculpture will be made available on the museum’s website for everyone to see, study, and enjoy. The digitization work will be completed over three years. Visit collection.folkartmuseum.org/collections to see more and check back frequently as new items are being uploaded constantly. AMERICAN FOLK ART MUSEUM COLLECTIONS AND EDUCATION CENTER 2 LINCOLN SQUARE, (COLUMBUS AVENUE BETWEEN 47-29 32ND PLACE, LONG ISLAND CITY, NY 65TH AND 66TH STREETS), NEW YORK, NY 11101-2409 10023-6214 212. 595. 9533 | WWW.FOLKARTMUSEUM.ORG [email protected] AMERICAN FOLK ART MUSEUM ANNUAL REPORT FISCAL YEAR 2017 WELCOME LETTER 2 Dr. Anne-Imelda Radice INTRODUCTION 3 Monty Blanchard DASHBOARD 4 EXHIBITIONS 6 LOANS 14 PUBLICATIONS 15 EDUCATIONAL PROGRAMS 16 ADULT PUBLIC PROGRAMS 22 ARCHIVES AND LIBRARY 26 MUSEUM CAREER INTERNSHIP PROGRAM 27 MEMBERS AND FRIENDS 28 FALL BENEFIT GALA 30 MUSEUM SHOP 31 NEW ACQUISITIONS 32 FINANCIAL STATEMENTS 40 DONORS, FOLK ART CIRCLE, AND MEMBERS 42 BOARD OF TRUSTEES 45 STAFF 46 IN MEMORIAM 48 Left: Photo by Christine Wise. Copyright © 2018 by American Folk Art Museum, New York 1 Dear members and friends, FY 2017 was a banner year for the museum. The exhibitions received excellent reviews, major grants came in, and curators and publications received awards. -

Wavelength Midlo Center for New Orleans Studies

University of New Orleans ScholarWorks@UNO Wavelength Midlo Center for New Orleans Studies 4-1984 Wavelength (April 1984) Connie Atkinson University of New Orleans Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uno.edu/wavelength Recommended Citation Wavelength (April 1984) 42 https://scholarworks.uno.edu/wavelength/42 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Midlo Center for New Orleans Studies at ScholarWorks@UNO. It has been accepted for inclusion in Wavelength by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. APRIL 1984 Inside: Jazz Fest Schedule Chris Kenner George Dureau Photographs BULK RATE U.S POSTAGE PAID ALEXANDRIA, LA. PERMIT N0.69 C M A GA ZIN INTRODUCING 'MSAVE SUN BELT AUDIO VIDEO ENTERPRISES, FEATURES ADVANTAGES SAVE High output, low noise Dynamic range for true reproduction. The Best Tape The effects of pre- and post -echo ore Lowest print-through largely alleviated. Minimum 6 dB lower The Best Service print through compared to other topes Excellent slitting of its kind. The Best Price Consistency Consistent phose stability. Superior Immediate shipment winding characteristics. No slow from our floor stock. Tensilized base winding necessary. High frequency stability. The acknowledged Reliable mechanical and acoustical leader in Europe and properties lessen the need for machine United Kingdom realignment. now readily Insures tope life against transport available in the U.S. mishandling. AtlSTERS'' il'VYIIIIVI <liftefory Of etudrOS and ana teceive a FREE sample and phone listing to Louisiana 70458. ISSUE NO. 42 • APRll. 1984 For ISSN 0741 . 2460 New ''I'm not sure, but I'm almost positive, that all music came from New Orleans. -

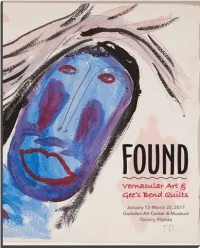

Foundcatalog 2017.Pdf

Found: Southern Vernacular Art & Gee’s Bend Quilts Presented by Bell & Bates Home Center • FSU College of Medicine Su and Steve Ecenia • Stacy Rehberg Photography Anne Jolley Thomas and Lyle McAlister The Pettit Family Fund • Calynne and Lou Hill Sponsored in part by the State of Florida, Department of State, Division of Cultural Afairs and the Florida Council on Arts and Culture. Funding for this program was provided through a grant from the Florida Humanities Council with funds from the National Endowment for the Humanities. Any views, fndings, conclusions or recommendations expressed in this publication do not necessarily represent those of the Florida Humanities Council or the National Endowment for the Humanities. Cover image: Thornton Dial, Sr., Life Go On, 1990, watercolor on paper, 30 x Grace Robinson, Executive Director 22.5 inches, Gadsden Arts Center & Museum Permanent Collection Angie Barry, Curator of Exhibitions & Collections Anissa Ford, Education Director © Gadsden Arts, Inc. 2017 Lexie Lobaina, Volunteer Coordinator Melanie Joyner, Bookkeeper All rights reserved. No portion of this catalog may be reproduced in any form Becky Reep, Museum Shop Manager by mechanical or electronic means (including photocopying, recording, or Earl Morrogh, Catalog Design information storage and retrieval) without permission from Gadsden Arts, Inc. Gadsden Arts Center & Museum 13 North Madison Street, Quincy, FL 32351 • (850) 875-4866 • www.gadsdenarts.org 1 2 Table of Contents Essays Works of Art in the Exhibition 55-57 Forward from the Executive Director by Grace Robinson 4-5 Index of Artists 58 A History that Refused to Die by William Arnett 6-11 Common Tongue: Vernacular Art in the Florida Artists American South Alyne Harris 28 by Bradley Sumrall 12-15 Edward “Mr. -

Bill Traylor

Bill Traylor 1853 Born in Dallas County, AL 1928 Moved to Montgomery, AL 1938 Met Charles Shannon on Monroe Street 1949 Died in Montgomery, AL Selected Solo Exhibitions 2020 Bill Traylor, Betty Cuningham Gallery, New York, NY, (Online exhibition) 2019-20 Bill Traylor, David Zwirner Gallery, New York, NY 2019 Bill Traylor, Betty Cuningham Gallery, New York, NY 2018-19 Between Worlds: The Art of Bill Traylor, Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, DC Outliers and American Vanguard Art, National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC; travelled to: High Museum of Art, Atlanta, GA; Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Los Angeles, CA 2014 Bill Traylor, Betty Cuningham Gallery, New York, NY 2013 Bill Traylor, Re-Discovering Genius, Carl Hammer Gallery, Chicago, IL 2012 - 13 Bill Traylor: Drawings from the Collections of the High Museum of Art and the Montgomery Museum of Fine Arts, High Museum of Art, Atlanta, GA; travelled to: Frist Center for the Visual Arts. Nashville, TN: Mingei International Museum, San Diego, CA; American Folk Art Museum, New York, NY Traylor in Motion: Wonders from New York Collections, American Folk Art Museum, New York, NY 2002 The Drawings of Bill Traylor, Montgomery Museum of Fine Art, Montgomery, AL 1999 Bill Traylor, Galerie Karsten Greve, Koln, Germany; travelled to Galerie Karsten Greve, Paris, France 1998-99 Bill Traylor. Deep Blues, Kunstmuseum Bern, Switzerland with Museum Ludwig, Koln, Germany; travelled to: Robert Hull Fleming Museum, Burlington, VT 1998 Bill Traylor’s Folk Art, Montgomery Museum of Fine Arts, -

The Studio Museum Announces Spring 2014 Exhibitions and Projects

MEDIA RELEASE The Studio Museum in Harlem 144 West 125th Street New York, NY 10027 studiomuseum.org/press Contact: Elizabeth Gwinn, Communications Manager [email protected] 212.864.4500 x213 The Studio Museum Announces Spring 2014 Exhibitions and Projects Henry Ray Clark, On Our Planet Name Yahoo We Are Called Destiny Childs We Sing and Dance to We do Know One Thing For Sure We Will Never Separate Are Be Apart, 2003. Courtesy Jack Massing NEW YORK, NY, February 10, 2014—This spring, The Studio Museum in Harlem debuts a slate of exhibitions and projects that challenge the boundaries of contemporary art practice and exhibition. Featuring more than fifty artists, championing collaboration and encompassing meditations on geography, history, fashion, sports and more, this season’s exhibitions promise to engage and inspire diverse audiences. When the Stars Begin to Fall: Imagination and the American South looks at the influence of self-taught artists on defining what black art can be, as well as the cultural significance of the American South as a geographic location and a conceptual frame. Including work by thirty-five artists who challenge the boundaries between self-taught, academically trained, religiously inspired and secular categorizations, When the Stars begin to Fall brings together work often displayed and considered separately. The exhibition Glenn Kaino: 19.83 takes its title from runner Tommie Smith’s gold medal–winning time in the men’s 200-meter race at the 1968 Olympic Games in Mexico City. The show features two major recent works that are part of an ongoing collaboration between Kaino and Smith.