Foundcatalog 2017.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Interpreting the Assemblages of Lonnie Holley Through His Performative Explanations

INTERPRETING THE ASSEMBLAGES OF LONNIE HOLLEY THROUGH HIS PERFORMATIVE EXPLANATIONS Sarah M. Schultz A thesis submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of the Master of Arts in the Department of Art. Chapel Hill 2010 Approved by: Dr. John P. Bowles Dr. Bernard L. Herman Dr. Pika Ghosh Dr. Ross Barrett © 2010 Sarah M. Schultz ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT SARAH M. SCHULTZ: Interpreting the Assemblages of Lonnie Holley through his Performative Explanations (Under the direction of Dr. John P. Bowles) For the past three decades, Lonnie Holley has collected materials alongside highways, ditches and in the landfills near his home in Birmingham, Alabama. These objects are used as the raw material for his assemblages. His artistic combinations suggest new relationships between once familiar, now obsolete technologies such as old television sets, computer screens, electrical wiring, barbed wire fencing, rebar, and molded concrete. Interpretations of his work rarely go beyond recounting his extraordinary personal narrative as the seventh of twenty-seven children. This comes at the expense of an in-depth critical analysis of his material and the new relationships he creates in his assemblages. Through a critical analysis of three of his major works, The Inner Suffering of the Holy Cost, Little Top to the Big Top, and Cold Titty Mama I, this study explores how his materials are re-valued, or given new meaning when they are combined. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This thesis has benefitted from a wealth of perspectives. I am especially thankful for the patience of my advisors Dr. -

Walks to the Paradise Garden, a Lowdown Southern

July 1, 2019 Walks to the Paradise Garden: A Lowdown Southern Odyssey, ed. Phillip March Jones Richard B. Woodward JTF (just the facts): Published in 2019 by Institute 193 (here) to coincide with the exhibition Way Out There: The Art of Southern Backroads at the High Museum of Art in Atlanta (March 2-May 19, 2019). Hardcover, 352 pages, with 100 color and 80 black-and-white photographic reproductions. Organized as a collection of writings by Jonathan Williams with photographs by Roger Manley and Guy Mendes. (Cover and spread shots below.) Comments/Context: Jonathan Williams (1929-2008) was one of the wild cards of American arts and letters. Poet, publisher, photographer, folklorist, gadfly, he devoted his sizable energies and learning as an adult to seeking out and championing the culturally marginalized. Williams wrote this manuscript in the early 1990s, an account of journeys made in the 1980s with friends Roger Manley and Guy Mendes, as they rode around the backroads of the Southeastern United States (except for Florida where Williams refused to go) in search of native oddballs and visionaries. This was an era before Outsider Art Fairs became regular events and self-taught artists were esteemed by museum curators and collectors. We are therefore given early and privileged access to numerous figures (Howard Finster, Martha Nelson, Thornton Dial, Henry Speller, Harold Garrison, Annie Hooper, Edgar Tolson, James Harold Jennings, Vollis Simpson, Sister Gertrude Morgan) prior to their academic and monetary validation. In his Editor’s Note, Phillip March Jones, who has worked to preserve the tangy flavor of Williams’ vinegary prose while correcting a few errors, writes that this book offers “one last look at the artists and place-makers of the Southern United States before the arrival of a new and interconnected world.” Although in some ways an art historical document of the period, with time-stamped references to the 1991 Iraq War, among other Bush-era asides, it is also a self-portrait. -

July 1, 2012–June 30, 2013 FY13: a LOOK BACK

Georgia Museum of Art Annual Report July 1, 2012–June 30, 2013 FY13: A LOOK BACK One of the brightest spots of FY13 was the On October 22, the museum celebrated inaugural UGA Spotlight on the Arts, a nine-day its official reaccreditation by the American festival held November 3–11, highlighting visual, Alliance of Museums (formerly the American performing, and literary arts all over campus, Association of Museums). Although the in which the museum participated eagerly. The museum is usually closed on Mondays, it was vision of vice-provost Libby Morris, the festival open to the public for the day. AAM director was planned by the UGA Arts Council, of which Ford Bell attended the event and spoke about museum director William U. Eiland is a member, the museum, followed by an ice cream social. and its subsidiary public relations arm (at Less than 5 percent of American museums are which Michael Lachowski and Hillary Brown accredited, and the process is not a simple one. represented the museum). The festival attracted Reaccreditation is a lengthy process, involving great attendance, especially from students, and a self-study that the museum worked on for demonstrated the administration’s commitment several years and a site visit lasting several days, to making the arts an essential part of the during which AAM representatives toured the university experience. Later in the fiscal year, the facility from top to bottom, met with university Arts Council began working on a strategic plan, upper administration, and interviewed staff with brainstorming meetings held by both the members, volunteers, students, and patrons of executive and PR committees in the museum’s the museum. -

Appropriation Art Tate: Appropriation

Appropriation Art Tate: Appropriation https://www.tate.org.uk/art/art-terms/a/appropriation Appropriation! When Art (very closely) Inspires Other Art https://magazine.artland.com/appropriation-when-art-very-closely-inspires-other-art/#: ~:text=Beginning%20in%20the%201960s%20Richard,of%20the%20newly%2Dfamous %20masterworks. Sandra Cinto https://mymodernmet.com/sandra-cinto-encontro-das-aguas/ Marcel Duchamp https://blog.singulart.com/en/2020/05/14/lhooq-1919-marcel-duchamps-uncompromis ing-piece/ Jasper Johns + https://www.thecollector.com/pop-art-famous-iconic/ Richard Pettibone https://www.artsy.net/artwork/richard-pettibone-jasper-johns-flag-1955 A 10 Year Long Art History Course - Vincent Desiderio’s Cockaigne https://archive.nytimes.com/www.nytimes.com/ref/arts/design/01FINE.html?pagewant ed=all Diana Al-Hadid Plays the Classics https://youtu.be/McVvi4GVS6U CanadianArt | Dirty Words: Appropriation https://canadianart.ca/features/dirty-words-appropriation/ Protest Art Zimmerli Art Museum http://www.zimmerlimuseum.rutgers.edu/information/visitors#.YKFrNWZKg6A Wikipedia: Hi-Red Center https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hi-Red_Center Guerrilla Girls https://www.guerrillagirls.com/ Wikipedia: Diamanda Galása https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Diamanda_Gal%C3%A1s Protesters Block, Demand Removal of a Painting of Emmett Till at the Whitney Biennial https://hyperallergic.com/367012/protesters-block-demand-removal-of-a-painting-of-e mmett-till-at-the-whitney-biennial/ Outsider Art 10 things to know about Jean Dubuffet https://www.christies.com/features/10-things-to-know-about-Jean-Dubuffet-8066-1.asp x The inside track on Outsider Art the artists to know https://www.christies.com/features/Outsider-Artists-Hot-List-7598-1.aspx#:~:text=First %20coined%20by%20the%20critic,of%20the%20mainstream%20art%20world. -

Annual Report Fiscal Year 2016 American Folk Art Museum July 1, 2015–June 30, 2016

ANNUAL REPORT FISCAL YEAR 2016 AMERICAN FOLK ART MUSEUM JULY 1, 2015–JUNE 30, 2016 The American Folk Art Museum received a grant from the Friends of Heritage Preservation to conserve a work by Thornton Dial. The conservation treatment was carried out by conservators Barbara Appelbaum and Paul Himmelstein, of Appelbaum & Himmelstein, LLC. They have decades of experience working on paintings, textiles, and folk art, including extensive work on the museum’s collection. The Friends of Heritage Preservation is a small, private association of individuals, based in Los Angeles, who seek to promote cultural identity through the preservation of significant endangered artistic and historic works, artifacts, and sites. AMERICAN FOLK ART MUSEUM COLLECTIONS AND EDUCATION CENTER 2 LINCOLN SQUARE, (COLUMBUS AVENUE BETWEEN 47-29 32ND PLACE, LONG ISLAND CITY, NY 65TH AND 66TH STREETS), NEW YORK, NY 11101-2409 10023-6214 212. 595. 9533 | WWW.FOLKARTMUSEUM.ORG [email protected] The Man Rode Past His Barn to Another New Day, Thornton Dial Sr. (1928–2016), Bessemer, Alabama, 1994–1995, oil and enamel on canvas with clothing, carpet, rope, wire, and industrial sealing compound, 84 x 120", gift of Jane Fonda, 2001.2.1. Photo by Gamma One. AMERICAN FOLK ART MUSEUM ANNUAL REPORT FISCAL YEAR 2016 WELCOME LETTER 2 Dr. Anne-Imelda Radice INTRODUCTION 3 Monty Blanchard DASHBOARD 4 EXHIBITIONS 6 LOANS AND AWARDS 16 PUBLICATIONS 17 EDUCATIONAL PROGRAMS 18 ADULT PUBLIC PROGRAMS 24 COLLECTIONS AND EDUCATION CENTER 28 MUSEUM CAREER INTERNSHIP PROGRAM 29 MEMBERS AND FRIENDS 30 FALL BENEFIT GALA 32 MUSEUM SHOP 33 NEW ACQUISITIONS 34 FINANCIAL STATEMENTS 40 DONORS, FOLK ART CIRCLE, AND MEMBERS 42 BOARD OF TRUSTEES 45 STAFF 46 IN MEMORIAM 48 Left: Photo by Christine Wise. -

July 1, 2015–June 30, 2016 FY16: a LOOK BACK

Georgia Museum of Art Annual Report July 1, 2015–June 30, 2016 FY16: A LOOK BACK This fiscal year, running from July 1, 2015, a dramatic uptick in attendance during the to June 30, 2016, was, as usual, packed with course of the show. Heather Foster, an MFA activities at the Georgia Museum of Art. The student at UGA in painting and an intern in exhibition El Taller de Gráfica Popular: Vida y our education department, created a series of Arte kicked off our fiscal year, providing the Pokemon-inspired cards highlighting different inspiration for our summer Art Adventures objects in the exhibition. We also embarked programming in 2015 as well as lectures, upon our first Georgia Funder, using UGA’s films, family programs and much more. We crowd-funding platform to raise money for the engaged in large amounts of Spanish-language exhibition’s programming. Caroline Maddox, programming, and the community responded our director of development, left for a position positively. at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, and Laura Valeri, associate curator, for Georgetown In July, the Friends of the Georgia Museum University Press. of Art kicked off a three-month campaign to boost membership by 100 households. Through In November, we focused attention on three carefully crafted marketing emails and the first major gifts from the George and Helen Segal in a series of limited-edition mugs available only Foundation, devoting an entire exhibition to through membership, they did just that and them. Other major acquisitions included a more. painting by Frederick Carl Frieseke (due to the generosity of the Chu Family Foundation), one In August, with the beginning of the university’s by Anthony Van Dyck and studio (from Mr. -

Final Project

Brown 1 Pierson Brown ARTH-432 Professor Elder 3 May 2021 Painting Through Faith: Self-Taught Artists of the American South Exhibition Link: https://www.artsteps.com/view/608f03fe51f030f9968b0ed0?currentUser I. Theme The theme for this exhibition proposal is Christianity and its influence on self-taught artists of the American South in the 1970s. II. Project Proposal In this exhibition, entitled Painting Through Faith: Self-Taught Artists of the American South, the focus lies on three artists: Sister Gertrude Morgan, Howard Finster, and Purvis Young. Each of these artists represent different areas of the American South, respectively from New Orleans, Louisiana, Rome, Georgia, and Miami, Florida. As this exhibition will show, their religious conviction and desire to create art permeates barriers of location, racial identity, and gender identity. Each artist is represented by 4 paintings that best exemplify their particular style and religious passion. This provides enough context to place the artists in conversation with one another and allow for thought provoking discussion from the visitors and intellectuals. The theme of this exhibition captures the role of religion in the practices of Southern self-taught artists. More particularly, Painting Through Faith investigates how the practice of Christianity and folk art permeated boundaries of race and gender just after the height of the Civil Rights Movement in the 1970s. Each work included was created in the 1970s and the included text prompts viewers to view the paintings with the Civil Rights Movement in mind. As Brown 2 the country was just recently engaged in a period of both terror and hope, these artists offer a unique perspective of how their environment shaped their perspective. -

Print ED394899.TIF

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 394 899 SO 026 502 AUTHOR Patterson, To TITLE ASHE: Improvisation & Recycling in African-American Visionary Art. INSTITUTION Winston-Sales State Univ., NC. Diggs Gallery. SPONS AGENCY North Carolina Arts Council, Raleigh. PUB DATE 93 NOTE 41p.; Printed on colored paper with color photographs and may not reproduce well. Funding also received from the James T. Diggs Memorial Fund and the United Arts Council of Winston-Salem and Forsyth County. PUB TYPE Reference Materials Directories/Catalogs (132) Viewpoints (Opinion/Position Papers, Essays, etc.) (120) EDRS PRICE MF01 /PCO2 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Art Education; Arts Centers: *Black Achievement; *Blacks; Reference Materials; Secondary Education; *Visual Arts IDENTIFIERS African Americans ABSTRACT This exhibition guide provides critical analysis, historical perspective, and brief biographies of 15 self-taught African-American artists whose works were displayed. "Ashe," an African word meaning "the power to make things happen," was used as the theme of the exhibition. The guide verbalizes the exhibit's investigation of the methods of making art and the motives of the makers by exploring the choice of materials (recycled objects) and the modes of creation (improvisational). Chapter one is entitled "Sorting Out a Context for Self-taught Art." The critique also examines the works' intellectual lineage traced from African spiritualism. Artists featured in this exhibition are: (1) E. M. Bailey; (2) Hawkins Bolden; (3) T. J. Bowman;(4) Thornton Dial; (5) Thornton Dial, Jr.; (6) Ralph Griffin; (7) Bessie Harvey; (8) Lonnie Holley; (9) Joe Light; (10) Ronald Lockett; (11) Charlie Lucas; (12) Leroy Person; (13) Juanita Rogers; (14) Arthur Spain; and (15) Jimmie Lee Sudduth. -

Thornton Dial.” in Elsa Longhauser and Harald Szeeman, Eds

“Thornton Dial.” In Elsa Longhauser and Harald Szeeman, eds. Self- Taught Artists of the 20th Century. New York: Museum of American Folk Art, 1998; pp. 174-179+204. Text © Robert Hobbs 1 7 4 Since 1987 brother Arthur. The Thornton Dial's paint THORNTON two boys first lived ings and sculpture have with their great-grand challenged and trans DIAL SR. mother Martha James formed standard con (b. 1928) Bell; after her death and ceptions of folk art. In BORN EMELLE, ALABAMA their Stlbsequent move his work he confronts WORKS BESSEMER, ALABAMA to an aunt's home for such issues as racism approximately two years, and civil rights, ecology, BI MBFRT uguus they moved to Bessemer. sexual politics , the Here they were brought homeless, natural disasters, the plight of veterans, up by their great-aunt Sarah Dial Lockett, to whom industrialism and postindustrialism, the death of Dial remained devoted until her death in 1995. the American city, and unemployment. Dial's life in Over the years, Dial has worked at a num rural and urban Alabama was not very different ber of jobs, often holding two or three simultane from the common ously, as well as planting big gardens and raising experience of blacks livestock. His main employment, with Pullman in the first half of Standard, involved him in most of its departments, the twentieth century including punch and shear, "vhere in the 1970s he who migrated from assumed the critical role of running the center rural tenant farms seals to the foundations of boxcars. He remained to industrial areas. -

With His Work Heading to Next Year's Venice Biennale, the Late Artist

With His Work Heading to Next Year’s Venice Biennale, the Late Artist Purvis Young Transcends the ‘Outsider’ Label The work of the energetic self-taught artist has become increasingly accepted into the institutional art world. artnet Gallery Network, September 5, 2018 Purvis Young, Angel and Warriors (c. 2007). Courtesy of Skot Foreman Gallery. The term “outsider artist” has been controversial since Roger Cardinal first coined it in the early 1970s. While it’s still part of the art-world lexicon, for some gallerists, the phrase feels particularly restrictive. “It’s limiting, for sure. You’re forced to start off conversations with prospective clients by defending the work,” says veteran New York dealer Skot Foreman. “It’s a handicap. It’s an obstacle, but one that I think can be overcome.” Foreman should know a thing or two about overcoming this kind of obstacle. One of his biggest and most successful clients is artist Purvis Young, who has been labeled an outsider artist since first being discovered in Miami in the 1970s. Indeed, Young had all the hallmarks that we associate with the outsider perspective: He came from humble origins, living for much of his life in poverty in Overtown, a predominantly black neighborhood on the outskirts of Miami; he was self-trained, picking up all his skill and knowledge from library books rather than art schools; and he often used found objects in his work, from cardboard to crates to doors to just about anything that paint would stick to. Purvis Young. Courtesy of Skot Foreman Gallery. Some 50 years later, the “outsider” label still clings to his legacy, despite the fact that his career transcended it time and time again. -

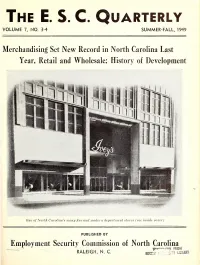

The E.S.C. Quarterly

The E. S. C. Quarterly VOLUME 7, NO. 3-4 1949 SUMMER-FALL # Merchandising Set New Record in North Carolina Last Year, Retail and Wholesale; History of Development ** One of North Carolina's many fine and modern department stores (see inside cover) PUBLISHED BY Employment Security Commission of North Carolina jpttm^awm FROM RALEIGH, N. C. - B^Y L : ;sTy im PAGE 82 THE E. S. C. QUARTERLY Summer-fall, 1949 The E. S. C. Quarterly MERCHANDISING IN STATE (Formerly The U.C.C. Quarterly) Merchandising in North Carolina is big business. Both wholesale and retail trade has developed and Volume 7, Numbers 3-4 Summer-Fall, 1949 expanded in the State to keep pace with the ever Issued four times a year at Raleigh, N. C, by the growing demands of the State's citizenship for more and EMPLOYMENT SECURITY COMMISSION OF better merchandise. Retail trade exceeded $2,- NORTH CAROLINA 137,000,000 during the fiscal year ended last June 30, and the North Carolina Department of Revenue does Commissioner:-;: Mrs. Quentin Gregory, Halifax; Dr. Harry D. not claim that these figures tell the complete story. Wolf, Chapel Hill; R. Dave Hall, Belmont; Marion W. Heiss, Much trading does not go on the records. Greensboro; C. A. Fink, Spencer; Bruce E. Davis, Charlotte. But the retail trade produced through the 3% sales and use State Advisory Council: Dr. Thurman D. Kitchin, Wake For- tax more than $40,000,000 in taxes, which is the est, chairman; Mrs. Gaston A. Johnson, High Point; W. B. Horton, Yanceyville; C. P. Clark, Wilson; Dr. -

Fiamagazine Board of Trustees 1 Elizabeth S

SPRING 2021 fiamagazine Board of Trustees 1 Elizabeth S. Murphy, President From the Executive Director CONTENTS Thomas B. Lillie, First Vice-President Mark L. Lippincott, Second Vice- President When the pandemic’s grip on our patterns programming to be a suitable alternative executive director 1 news & programs 18–24 Elisabeth Saab, Secretary Martha Sanford, Treasurer of socialization and communication is to visiting in person during the pandemic. exhibitions 2–10 education 25 John Bracey Eleanor E. Brownell finally over, we can expect the experience Since June 2020, we’ve seen a 29% increase art on loan 11 art school 26 Ann K. Chan will have changed our behavior in many in our Facebook page’s total impressions James D. Draper, Founders Society acquisitions 12–13 contributions 27–29 President ways. During the March through June and the total number of engagements are Mona Hardas calendar 14–15 membership 30–32 Carol Hurand shutdown at the FIA, social media outlets, up 12.5%. The FIA’s Instagram accounts Lynne Hurand our website, and e-news were the only continue to grow steadily. The open and films 15–17 museum shop 33 Raymond J. Kelly III, FIA Representative to FCCC Board way we could keep the museum “open” click-to-open rates for our eNewsletters Alan Klein Jamile Trueba Lawand to our public. And while the importance are well above the average for Art, Culture, Eureka McCormick of digital or virtual communication has Entertainment. Since the beginning of William H. Moeller Jay N. Nelson been increasingly understood over the March 2020, the website has seen a 16.5% Office Hours Admission Karl A.