George Enescu His Influence As a Violinist and Pedagogue

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

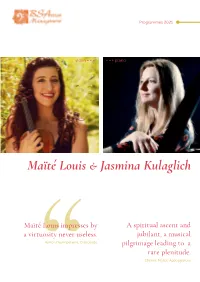

Maïté Louis & Jasmina Kulaglich

Programmes 2021 violin • • • • • • piano Maïté Louis & Jasmina Kulaglich Maïté Louis impresses by A spiritual ascent and a virtuosity never useless. jubilant, a musical Ayrton Desimpelaere, Crescendo pilgrimage leading to a rare plenitude. “ Etienne Muller, Appoggiature Biography Maïté Louis, violin An atypical personality in the world of classical This particularity of her career, this refusal to fit into music, Maïté Louis makes a lasting impression the prefabricated mould of soloists, this attach- with his overwhelming playing and extraordinary ment to finding music at the heart of everything, stage presence. make her the unique and rich artist she is today. Winner of numerous national and internation- al competitions (1st prize at the Golden Classical When Maïté Louis makes Music Awards in New York, 1st prize at the Interna- “ tional Grand Prize Virtuoso Competition in Rome, 2nd prize at the Glazounov International Compe- her violin cry, that’s all the tition, Silver Medal at the Ivo Pogorelich Interna- hall crying with her tional Competition in Manhattan, 3rd prize at the Le Dauphin Rising Star International Competition in Berlin, Prix d’Honneur de France Musique...), often praised by Some of these concerts: Berlioz Festival, Festival her peers, she divides her time between her ca- d’Auvers sur Oise, Grand Odéon in Paris, Festival reer as a soloist on the great classical stages and des Musiques Rares, Salle Cortot in Paris, Festival teaching at the Geneva Conservatory. Multirythmes, Bonlieu Scène Nationale d’Annecy, “Festival d’Evian, Festival Interceltique de Lorient, Her extreme virtuosity, combined with her ex- Festival Jeunes Talents, Palais des Congrès de traordinary expressiveness and musical sensitivity, Megève, Académie de Villecroze, Archipel Scène wonderfully serves the entire range of the great Nationale de Guadeloupe,.. -

University of Cincinnati

UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI Date:___________________ I, _________________________________________________________, hereby submit this work as part of the requirements for the degree of: in: It is entitled: This work and its defense approved by: Chair: _______________________________ _______________________________ _______________________________ _______________________________ _______________________________ VIOLIN ETUDES: A PEDAGOGICAL GUIDE A document submitted to the Division of Research and Advanced Studies of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS in the Performance Studies Division of the College-Conservatory of Music 2006 by Semi Yang [email protected] B.M., Queensland Conservatorium of Music, Griffith University, Australia, 1995 M.M., Queensland Conservatorium of Music, Griffith University, Australia, 1999 Advisor: Dr. Won-bin Yim Reader: Prof. Kurt Sassmannshaus Reader: Dr. Robert Zierolf ABSTRACT Studying etudes is one of the most essential parts of learning a specific instrument. A violinist without a strong technical background meets many obstacles performing standard violin literature. This document provides detailed guidelines on how to practice selected etudes effectively from a pedagogical perspective, rather than a historical or analytical view. The criteria for selecting the individual etudes are for the goal of accomplishing certain technical aspects and how widely they are used in teaching; this is based partly on my experience and background. The body of the document is in three parts. The first consists of definitions, historical background, and introduces different of kinds of etudes. The second part describes etudes for strengthening technical aspects of violin playing with etudes by Rodolphe Kreutzer, Pierre Rode, and Jakob Dont. The third part explores concert etudes by Wieniawski and Paganini. -

18.7 Instrumental 78S, Pp 173-195

78 rpm INSTRUMENTAL Sets do NOT have original albums unless indicated. If matrix numbers are needed for any of the items below in cases where they have been omitted, just let me know (preferably sooner rather than later). Albums require wider boxes than I use for records. If albums are available and are wanted, they will have to be shipped separately. U.S. postal charges for shipment within the U.S. are still reasonable (book rate) but out of country fees will probably be around $25.00 for an empty album. Capt. H. E. ADKINS dir. KNELLER HALL MUSICIANS 2107. 12” PW Plum HMV C.2445 [2B2922-IIA/2B2923-IIA]. FANFARES (Composed for the Musicians’ Benevolent Fund by Lord Berners, Sir. W. Davies, Dorothy Howell and Dame Edith Smyth). Two sides . Lt. rubs, cons . 2. $15.00. JOHN AMADIO [flutist] 2510. 12” Red Orth. Vla 9706 [Cc8936-II/Cc8937-II]. KONZERTSTÜCK, Op. 98: Finale (Heinrich Hofmann) / CONCERTINO, Op. 102 (Chaminade). Orch. dir. Lawrance Collingwood . Just about 1-2. $12.00. DANIELE AMFITHEATROF [composer, conductor] dir. PASDELOUP ORCH. 3311. 12” Green Italian Columbia GQX 10855, GQX 10866 [CPTX280-2/ CPTX281-2, CPTX282-3/ CPTX283- 1]. PANORAMA AMERICANO (Amfitheatrof). Four sides. Just about 1-2. $25.00. ENRIQUE FERDNANDEZ ARBOS [composer, conductor] dir. ORCH. 2222. 12” Blue Viva-Tonal Columbia 67607-D [WKX-62-2/WKX-63]. NOCHE DE ARABIA (Arbos). Two sides. Stkr. with Arbos’ autograph attached to lbl. side one. Just about 1-2. $20.00. LOUIS AUBERT [composer, con- ductor] dir. PARIS CONSERVA- TOIRE ORCH. 1570. 10” Purple Eng. -

Season 2014-2015

27 Season 2014-2015 Thursday, May 7, at 8:00 Friday, May 8, at 2:00 The Philadelphia Orchestra Saturday, May 9, at 8:00 Cristian Măcelaru Conductor Sarah Chang Violin Ligeti Romanian Concerto I. Andantino— II. Allegro vivace— III. Adagio ma non troppo— IV. Molto vivace First Philadelphia Orchestra performances Beethoven Symphony No. 1 in C major, Op. 21 I. Adagio molto—Allegro con brio II. Andante cantabile con moto III. Menuetto (Allegro molto e vivace)—Trio— Menuetto da capo IV. Adagio—Allegro molto e vivace Intermission Dvořák Violin Concerto in A minor, Op. 53 I. Allegro ma non troppo—Quasi moderato— II. Adagio ma non troppo—Più mosso—Un poco tranquillo, quasi tempo I III. Finale: Allegro giocoso ma non troppo Enescu Romanian Rhapsody in A major, Op. 11, No. 1 This program runs approximately 1 hour, 50 minutes. The May 7 concert is sponsored by MedComp. The May 8 and 9 concerts are sponsored by the Blanche and Irving Laurie Foundation. designates a work that is part of the 40/40 Project, which features pieces not performed on subscription concerts in at least 40 years. Philadelphia Orchestra concerts are broadcast on WRTI 90.1 FM on Sunday afternoons at 1 PM. Visit www.wrti.org to listen live or for more details. 228 Story Title The Philadelphia Orchestra Jessica Griffin The Philadelphia Orchestra is one of the preeminent orchestras in the world, renowned for its distinctive sound, desired for its keen ability to capture the hearts and imaginations of audiences, and admired for a legacy of imagination and innovation on and off the concert stage. -

Karl Schuricht Concerto En Ré Majeur - Op

Karl Schuricht Concerto En Ré Majeur - Op. 77 Pour Violon Et Orchestre mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Classical Album: Concerto En Ré Majeur - Op. 77 Pour Violon Et Orchestre Country: France Style: Romantic MP3 version RAR size: 1276 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1586 mb WMA version RAR size: 1954 mb Rating: 4.2 Votes: 930 Other Formats: XM AA APE FLAC AIFF ASF WAV Tracklist Concerto En Ré Majeur - Op. 77 Pour Violon Et Orchestre A1 Allegro Non Troppo (Cadence De Kreisler) B1 Adagio Allegro Giocoso, Ma Non Troppo Vivace (Cadence De B2 Kreisler) Companies, etc. Printed By – Dehon & Cie Imp. Paris Credits Liner Notes – Claude Rostand Barcode and Other Identifiers Rights Society: DP Other versions Category Artist Title (Format) Label Category Country Year Johannes Brahms, Johannes Brahms, Christian Ferras, Christian Ferras, Wiener Philharmoniker, LXT 2949 Wiener Carl Schuricht - Decca LXT 2949 UK Unknown Philharmoniker, Carl Concerto In D Major For Schuricht Violin And Orchestra Opus 77 (LP, Album) Carl Schuricht - Carl Schuricht - Christian Ferras - Christian Ferras - 6.42142 Johannes Brahms - 6.42142 Johannes Brahms - Decca Germany Unknown AF Wiener Philharmoniker - AF Wiener Violinkonzert D-Dur (LP, Philharmoniker Album) Carl Schuricht - Christian Ferras - Carl Schuricht - Johannes Brahms - Christian Ferras - Wiener Philharmoniker - LXT 2949 Johannes Brahms - Decca LXT 2949 Spain 1958 Concierto En "Re" Wiener Mayor Para Violín y Philharmoniker Orquesta Opus 71 (LP, Album, Mono) Johannes Brahms, Christian Ferras, Vienna Johannes Brahms, Philharmonic Christian Ferras, Orchestra*, Carl B 19018 Vienna Philharmonic Richmond B 19018 Mexico Unknown Schuricht - Concerto In Orchestra*, Carl D Major For Violin And Schuricht Orchestra Opus 77 (LP, Album) Carl Schuricht - Carl Schuricht - Christian Ferras - Christian Ferras - LW 50095 Johannes Brahms - Johannes Brahms - Decca LW 50095 Germany Unknown Wiener Wiener Philharmoniker - Philharmoniker Violinkonzert D-Dur (LP) Related Music albums to Concerto En Ré Majeur - Op. -

Digibooklet Antonio Janigro

ANTONIO JANIGRO & ZAGREG SOLOISTS Berlin, 1957-1966 ARCANGELO CORELLI (1653-1713) Concerto grosso in D major, Op. 6/4 I. Adagio – Allegro 2:32 II. Adagio 2:03 SOLOISTS III. Vivace 1:09 IV. Allegro – 1:58 V. Allegro 0:41 Gunhild Stappenbeck, Cembalo Continuo recording: 14-01-1957 GIOACHINO ROSSINI (1792-1868) Sonata for Strings No. 6 in D major I. Allegro spiritoso 6:32 II. Andante assai 2:39 ZAGREG III. Tempesta. Allegro 5:12 recording: 19-04-1964 & PAUL HINDEMITH (1895-1963) Trauermusik (Funeral Music) for Solo Viola and Strings I. Langsam 4:28 II. Ruhig bewegt 1:25 III. Lebhaft 1:32 IV. Choral „Für deinen Thron“ 2:24 Stefano Passaggio, solo viola recording: 12-03-1958 JANIGRO DMITRI SHOSTAKOVICH (1906-1975) Octet for Strings, Op. 11 II. Scherzo recording: 17-04-1964 SAMUEL BARBER (1910-1981) Adagio for Strings recording: 19-04-1964 ANTONIO ANTONIO MILKO KELEMEN (*1924) Concertante Improvisations for Strings I. Allegretto 2:20 II. Andante sostenuto – Allegro giusto 2:05 SOLOISTS III. Allegro scherzando 1:15 IV. Molto vivace quasi presto 2:05 recording: 12-03-1958 MAX REGER (1873-1916) Lyric Andante for String Orchestra5:18 recording: 16-03-1966 WOLFGANG AMADEUS MOZART (1756-1791) Divertimento in B-flat major, K. 137 ZAGREG I. Andante 4:10 II. Allegro di molto 2:44 & III. Allegro assai 2:17 recording: 19-03-1961 ROMAN HOFFSTETTER (1742-1815), former attrib. to JOSEPH HAYDN (1732-1809) Serenade in C major (from Op. 3/5) recording: 11-11-1958 ANTONIO VIVALDI (1678-1741) Concerto in D major, RV 230 (Cello Version) JANIGRO I. -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Season 27,1907-1908, Trip

CARNEGIE HALL - - NEW YORK Twenty-second Season in New York DR. KARL MUCK, Conductor fnigrammra of % FIRST CONCERT THURSDAY EVENING, NOVEMBER 7 AT 8.15 PRECISELY AND THK FIRST MATINEE SATURDAY AFTERNOON, NOVEMBER 9 AT 2.30 PRECISELY WITH HISTORICAL AND DESCRIP- TIVE NOTES BY PHILIP HALE PUBLISHED BY C. A. ELLIS, MANAGER : Piano. Used and indorsed by Reisenauer, Neitzel, Burmeister, Gabrilowitsch, Nordica, Campanari, Bispham, and many other noted artists, will be used by TERESA CARRENO during her tour of the United States this season. The Everett piano has been played recently under the baton of the following famous conductors Theodore Thomas Franz Kneisel Dr. Karl Muck Fritz Scheel Walter Damrosch Frank Damrosch Frederick Stock F. Van Der Stucken Wassily Safonoff Emil Oberhoffer Wilhelm Gericke Emil Paur Felix Weingartner REPRESENTED BY THE JOHN CHURCH COMPANY . 37 West 32d Street, New York Boston Symphony Orchestra PERSONNEL TWENTY-SEVENTH SEASON, 1907-1908 Dr. KARL MUCK, Conductor First Violins. Wendling, Carl, Roth, O. Hoffmann, J. Krafft, W. Concert-master. Kuntz, D. Fiedler, E. Theodorowicz, J. Czerwonky, R. Mahn, F. Eichheim, H. Bak, A. Mullaly, J. Strube, G. Rissland, K. Ribarsch, A. Traupe, W. < Second Violins. • Barleben, K. Akeroyd, J. Fiedler, B. Berger, H. Fiumara, P. Currier, F. Rennert, B. Eichler, J. Tischer-Zeitz, H Kuntz, A. Swornsbourne, W. Goldstein, S. Kurth, R. Goldstein, H. Violas. Ferir, E. Heindl, H. Zahn, F. Kolster, A. Krauss, H. Scheurer, K. Hoyer, H. Kluge, M. Sauer, G. Gietzen, A. t Violoncellos. Warnke, H. Nagel, R. Barth, C. Loefner, E. Heberlein, H. Keller, J. Kautzenbach, A. Nast, L. -

Harvard Conference (Re)Presenting American Muslims: Broadening the Conversation Conference Team

Harvard Conference (Re)Presenting American Muslims: Broadening the Conversation Conference Team Host and Co-Convener Co-Convener Alwaleed Islamic Studies Program Institute for Social Policy and at Harvard University: Understanding (ISPU): Dr. Ali Asani Kathryn M. Coughlin Farhan Latif Zeba Iqbal Professor of Indo- Executive Director, Prince Chief Operating Officer ISPU Research Team Muslim and Islamic Alwaleed bin Talal Islamic & Director of Policy Editor and Report Religion and Cultures; Studies Program Impact Author Director, Alwaleed Islamic Studies Program Co-Organizers Facilitators Maria Ebrahimji Hussein Rashid, PhD Nadia Firozvi Asim Rehman Journalist, Consultant, Founder, Islamicate, L3C Attorney in Former President, & Co-Founder, I Speak Washington, DC Muslim Bar Association For Myself Inc. of NY ISPU would like to acknowledge the generous supporters whose contributions made this report possible: Mohamed Elnabtity and Rania Zagho, Jamal Ghani, Mahmoud and Nada Hadidi, Mahmood and Annette Hai, Fasahat Hamzavi and Saba Maroof, Rashid Haq, Raghib Hussain, Mohammed Maaieh and Raniah Jaouni, Khawaja Nimr and Beenish Ikram, Ghulam Qadir and Huda Zenati, Nadia Roumani, Quaid Saifee and Azra Hakimi, Abubakar and Mahwish Sheikh, Haanei Shwehdi and Ilaaf Darrat, Ferras Zeni and Serene Katranji Participants (listed alphabetically) Zain Abdullah, PhD, Shakila Ahmad, Debbie Almontaser Sana Amanat, Shahed Amanullah Saud Anwar, Associate Professor President, Islamic President, Board of Editor, Marvel Founder, Multiple Mayor of Windsor, in the -

Violin Repertoire List

Violin Repertoire List In reverse order of difficulty (beginner books at top). Please send suggestions / additions to [email protected]. Version 1.1, updated 27 Aug 2015 List A: (Pieces in 1st position & basic notation) Fiddle Time Starters Fiddle Time Joggers Fiddle Time Runners Fiddle Time Sprinters The ABCs of Violin Musicland Violin Books Musicland Lollipop Man (Violin Duets) Abracadabra - Book 1 Suzuki Book 1 ABRSM Grade Book 1 VIolinSchool Editions: Popular Tunes in First Position ● Twinkle Twinkle Little Star ● London Bridge is Falling Down ● Frère Jacques ● When the Saints Go Marching In ● Happy Birthday to You ● What Shall We Do With the Drunken Sailor ● Ode to Joy ● Largo from The New World ● Long Long Ago ● Old MacDonald Had a Farm ● Pop! Goes the Weasel ● Row Row Row Your Boat ● Greensleeves ● The Irish Washerwoman ● Yankee Doodle Stanley Fletcher, New Tunes for Strings, Book 1 2 Step by Step Violin Play Violin Today String Builder Violin Book One (Samuel Applebaum) A Tune a Day I Can Read Music Easy Classical Violin Solos Violin for Dummies The Essential String Method (Sheila Nelson) Robert Pracht, Album of Easy Pieces, Op. 12 Doflein, Violin Method, Book 1 Waggon Wheels Superstudies (Mary Cohen) The Classical Experience Suzuki Book 2 Stanley Fletcher, New Tunes for Strings, Book 2 Doflein, Violin Method, Book 2 Alfred Moffat, Old Masters for Young Players D. Kabalevsky, Album Pieces for 1 and 2 Violins and Piano *************************************** List B: (Pieces in multiple positions and varieties of bow strokes) Level 1: Tomaso Albinoni Adagio in G minor Johann Sebastian Bach: Air on the G string Bach Gavotte in D (Suzuki Book 3) Bach Gavotte in G minor (Suzuki Book 3) Béla Bartók: 44 Duos for two violins Karl Bohm www.ViolinSchool.org | [email protected] | +44 (0) 20 3051 0080 3 Perpetual Motion Frédéric Chopin Nocturne in C sharp minor (arranged) Charles Dancla 12 Easy Fantasies, Op.86 Antonín Dvořák Humoresque King Henry VIII Pastime with Good Company (ABRSM, Grade 3) Fritz Kreisler: Berceuse Romantique, Op. -

Roots & Origins

Sunday 16 December 2018 7–9.15pm Tuesday 18 December 2018 7.30–9.45pm Barbican Hall LSO SEASON CONCERT ROOTS & ORIGINS Brahms Violin Concerto Interval ROMANIAN Debussy Images Enescu Romanian Rhapsody No 1 Sir Simon Rattle conductor Leonidas Kavakos violin These performances of Enescu’s Romanian Rhapsody No 1 are generously RHAPSODY supported by the Romanian Cultural Institute 16 December generously supported by LSO Friends Welcome Latest News On Our Blog We are grateful to the Romanian Cultural BRITISH COMPOSER AWARDS MARIN ALSOP ON LEONARD Institute for their generous support of these BERNSTEIN’S CANDIDE concerts. Sunday’s concert is also supported Congratulations to LSO Soundhub Associate by LSO Friends, and we are delighted to have Liam Taylor-West and LSO Panufnik Composer Marin Alsop conducted Bernstein’s Candide, so many Friends with us in the audience. Cassie Kinoshi for their success in the 2018 with the LSO earlier this month. Having We extend our thanks for their loyal and British Composer Awards. Prizes were worked closely with the composer across important support of the LSO, and their awarded to Liam for his Community Project her career, Marin drew on her unique insight presence at all our concerts. The Umbrella and to Cassie for Afronaut, into Bernstein’s music, words and sense of a jazz composition for large ensemble. theatre to tell us about the production. I wish you a very happy Christmas, and hope you can join us again in the New Year. The • lso.co.uk/more/blog elcome to this evening’s LSO LSO’s 2018/19 concert season at the Barbican FELIX MILDENBERGER JOINS THE LSO concert at the Barbican. -

The St. Petersburg String Quartet Alla Aranovskaya

THE ST. PETERSBURG STRING QUARTET ALLA ARANOVSKAYA, VIOLIN BORIS VAYNER, VIOLA ALLA KROLEVICH, VIOLIN LEONID SHUKAEV, CELLO ASSISTING ARTIST: PETER KOLKAY, BASSOON SUNDAY, JULY 4, 2010 AT 3PM PROGRAM STRING QUARTET IN B FLAT MAJOR, Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart K. 458 "Hunt" (1784) (1756-1791) Allegro vivace assai Menuetto: Moderato Adagio Adagio assai This is the 13th performance of the Hunt Quartet at Music Mountain QUINTET FOR BASSOON & STRINGS, OPUS 14 (1997) Russell Platt (1965.....) Slow Movement Song Still Slow-Fast This is the Music Mountain premier of the Platt Bassoon Quintet INTERMISSION (Intermission Recital by Students of the St. Petersburg International Music Academy) STRING QUARTET IN C MINOR, Johannes Brahms OPUS 51 # 1 (1873) (1833-1897) Allegro Romanze: Poco Adagio Allegretto molto moderato e comodo Allegro This is the 25th performance of the C Minor Quartet at Music Mountain ********************* Please join us immediately after the concert in Music Mountain House for a Post Concert discussion with Peter Kolkay and others of the Bassoon and its place in Chamber Music. THE ARTISTS THE ST. PETERSBURG STRING QUARTET The St. Petersburg String Quartet is one of Music Mountain's favorite guests, having played here every year since 1995. The Quartet was formed at what was then the Leningrad Conservatory. They went on to win major honors both in the Soviet Union and abroad. For over 25 years, they have toured the United States, Europe (both East and West) and Asia. Their recordings have been nominated for Grammies and have won honors in Stereo Review and Gramophone as well as the WQXR/Chamber Music America prize for best CD of 2001. -

Pablo Ferrandez-Castro, Cello

Pablo Ferrández-Castro, Cello Awarded the coveted ICMA 2016 “Young Artist of the Year”, and prizewinner at the XV International Tchaikovsky Competition, Pablo Ferrández is praised by his authenticity and hailed by the critics as “one of the top cellists” (Rémy Louis, Diapason Magazine). He has appeared as a soloist with the Mariinsky Orchestra, Vienna Symphony Orchestra, St. Petersburg Philharmonic, Stuttgart Philharmonic, Kremerata Baltica, Helsinki Philharmonic, Tapiola Sinfonietta, Spanish National Orchestra, RTVE Orchestra, Maggio Musicale Fiorentino, and collaborated with such artists as Zubin Mehta, Valery Gergiev, Yuri Temirkanov, Adam Fischer, Heinrich Schiff, Dennis Russell Davies, John Storgårds, Gidon Kremer, Ivry Gitlis and Anne-Sophie Mutter. Highlights of the 2016/17 season include his debut with BBC Philharmonic under Juanjo Mena, his debut at the Berliner Philharmonie with the Deutsches Symphonie-Orchester Berlin, his collaboration with Christoph Eschenbach playing Schumann’s cello concerto with the HR- Sinfonieorchester and with the Spanish National Symphony, the return to Maggio Musicale Fiorentino under Zubin Mehta, recitals at the Mariinsky Theater and Schloss-Elmau, a European tour with Kremerata Baltica, appearances at the Verbier Festival, Jerusalem International Chamber Music Festival, Intonations Festival and Trans-Siberian Arts Festival, his debuts with Orchestra Sinfonica Nazionale RAI, Barcelona Symphony Orchestra, Munich Symphony, Estonian National Symphony, Taipei Symphony Orchestra, Queensland Symphony Orchestra, and the performance of Brahms' double concerto with Anne-Sophie Mutter and the London Philharmonic Orchestra. Mr. Ferrández plays the Stradivarius “Lord Aylesford” (1696) thanks to the Nippon Music Foundation. .