Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ilzers Apollon Mission!

Jeden Dienstag neu | € 1,90 Nr. 32 | 6. August 2019 FOTOS: GEPA PICTURES 50 Wien 15 SEITEN PREMIER LEAGUE Manchester City will den Hattrick! ab Seite 21 AUSTRIA WIEN: VÖLLIG PUNKTELOS IN DEN EUROPACUP MARCEL KOLLER VS. LASK Aufwind nach dem Machtkampf Seite 6 Ilzers Apollon TOTO RUNDE 32A+32B Garantie 13er mit 100.000 Euro! Mission! Seite 8 Österreichische Post AG WZ 02Z030837 W – Sportzeitung Verlags-GmbH, Linke Wienzeile 40/2/22, 1060 Wien Retouren an PF 100, 13 Die Premier League live & exklusiv Der Auftakt mit Jürgen Klopps Liverpool vs. Norwich Ab Freitag 20 Uhr live bei Sky PR_AZ_Coverbalken_Sportzeitung_168x31_2018_V02.indd 1 05.08.19 10:52 Gratis: Exklusiv und Montag: © Shutterstock gratis nur für Abonnenten! EPAPER AB SOFORT IST MONTAG Dienstag: DIENSTAG! ZEITUNG DIE SPORTZEITUNG SCHON MONTAGS ALS EPAPER ONLINE LESEN. AM DIENSTAG IM POSTKASTEN. NEU: ePaper Exklusiv und gratis nur für Abonnenten! ARCHIV Jetzt Vorteilsabo bestellen! ARCHIV aller bisherigen Holen Sie sich das 1-Jahres-Abo Print und ePaper zum Preis von € 74,90 (EU-Ausland € 129,90) Ausgaben (ab 1/2018) zum und Sie können kostenlos 52 x TOTO tippen. Lesen und zum kostenlosen [email protected] | +43 2732 82000 Download als PDF. 1 Jahr SPORTZEITUNG Print und ePaper zum Preis von € 74,90. Das Abonnement kann bis zu sechs Wochen vor Ablauf der Bezugsfrist schriftlich gekündigt werden, ansonsten verlängert sich das Abo um ein weiteres Jahr zum jeweiligen Tarif. Preise inklusive Umsatzsteuer und Versand. Zusendung des Zusatzartikels etwa zwei Wochen nach Zahlungseingang bzw. ab Verfügbarkeit. Solange der Vorrat reicht. Shutterstock epaper.sportzeitung.at Montag: EPAPER Jeden Dienstag neu | € 1,90 Nr. -

Former Celtic and Southampton Manager Gordon Strachan Discusses Rangers' Recent Troubles, Andre Villas-Boas and Returning to Management

EXCLUSIVE: Former Celtic and Southampton manager Gordon Strachan discusses Rangers' recent troubles, Andre Villas-Boas and returning to management. RELATED LINKS • Deal close on pivotal day for Rangers • Advocaat defends spending at Rangers • Bet on Football - Get £25 Free You kept playing until you were 40 and there currently seems to be a trend for older players excelling, such as Giggs, Scholes, Henry and Friedel. What do you put this down to? Mine was due to necessity rather than pleasure, to be honest with you. I came to retire at about 37, but I went to Coventry and I was persuaded by Ron Atkinson, then by players at the club, and then by the chairman at the club, that I should keep playing so that was my situation. The secret of keeping playing for a long time is playing with good players. There have been examples of people playing on - real top, top players - who have gone to a lower level and found it really hard, and then calling it a day. The secret is to have good players around you, you still have to love the game and you have to look after yourself. You will find that the people who have played for a long time have looked after themselves really at an early age - 15 to 21 -so they have got a real base fitness in them. They trained hard at that period of time, and hard work is not hard work to them: it becomes the norm. How much have improvements in lifestyle, nutrition and other techniques like yoga and pilates helped extend players' careers? People talked about my diet when I played: I had porridge, bananas, seaweed tablets. -

Jose Mourinho: the Art of Winning: What the Appointment of the Special One Tells Us About Manchester United and the Premier League by Andrew J

Jose Mourinho: The Art of Winning: What the appointment of the Special One tells us about Manchester United and the Premier League by Andrew J. Kirby ebook Ebook Jose Mourinho: The Art of Winning: What the appointment of the Special One tells us about Manchester United and the Premier League currently available for review only, if you need complete ebook Jose Mourinho: The Art of Winning: What the appointment of the Special One tells us about Manchester United and the Premier League please fill out registration form to access in our databases Download here >> Paperback:::: 276 pages+++Publisher:::: CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform (August 19, 2016)+++Language:::: English+++ISBN-10:::: 1537012363+++ISBN-13:::: 978-1537012360+++Product Dimensions::::5.1 x 0.6 x 7.8 inches++++++ ISBN10 1537012363 ISBN13 978-1537012 Download here >> Description: The manager everyone loves to hate… Mercurial Portuguese manager Jose Mourinho, who regards himself as football’s equivalent of George Clooney, featured in his own blockbuster this summer when he took charge of Manchester United – the world’s biggest club. The news sent shockwaves through the Old Trafford faithful – generations of whom have pledged their loyalty to a succession of managerial legends including Sir Matt Busby and Sir Alex Ferguson. At the very outset of what promises to be a tumultuous season for the Red Devils, Andrew J Kirby investigates in his latest book Jose Mourinho: The Art of Winning whether the latest controversial move by the club’s owners is a marriage made in heaven or hell. Machiavellian schemer, marketing man’s dream, inspirational leader and motivator, arrogant “manager-lout”, Super Coach. -

Graham Budd Auctions Sotheby's 34-35 New Bond Street Sporting Memorabilia London W1A 2AA United Kingdom Started 22 May 2014 10:00 BST

Graham Budd Auctions Sotheby's 34-35 New Bond Street Sporting Memorabilia London W1A 2AA United Kingdom Started 22 May 2014 10:00 BST Lot Description An 1896 Athens Olympic Games participation medal, in bronze, designed by N Lytras, struck by Honto-Poulus, the obverse with Nike 1 seated holding a laurel wreath over a phoenix emerging from the flames, the Acropolis beyond, the reverse with a Greek inscription within a wreath A Greek memorial medal to Charilaos Trikoupis dated 1896,in silver with portrait to obverse, with medal ribbonCharilaos Trikoupis was a 2 member of the Greek Government and prominent in a group of politicians who were resoundingly opposed to the revival of the Olympic Games in 1896. Instead of an a ...[more] 3 Spyridis (G.) La Panorama Illustre des Jeux Olympiques 1896,French language, published in Paris & Athens, paper wrappers, rare A rare gilt-bronze version of the 1900 Paris Olympic Games plaquette struck in conjunction with the Paris 1900 Exposition 4 Universelle,the obverse with a triumphant classical athlete, the reverse inscribed EDUCATION PHYSIQUE, OFFERT PAR LE MINISTRE, in original velvet lined red case, with identical ...[more] A 1904 St Louis Olympic Games athlete's participation medal,without any traces of loop at top edge, as presented to the athletes, by 5 Dieges & Clust, New York, the obverse with a naked athlete, the reverse with an eleven line legend, and the shields of St Louis, France & USA on a background of ivy l ...[more] A complete set of four participation medals for the 1908 London Olympic -

Newsletter #13

Newsletter #13 Welcome to the latest edition of my irregular updates newsletter and thank you for your continued interest and support. More features this time about my latest additions, items I'd like, auctions and other interesting sites. As ever, clicking on the picture or highlighted text in each item below will take you to a more detailed site, either mine or the relevant one. Also, if you know of anyone else who might be interested in receiving this newsletter please ask them to get in touch with me via the site or perhaps YOU could provide me with their email address. Another highlight from my website Perhaps it's an oddity, but I don't care and I'm going to include this here. It's the earliest item that I have of anything resembling HTAFC memorabilia - a sadly incomplete newspaper report of Town's 6-1 West Riding Cup 2nd Round tie against Clayton West on 20th March, 1909 at a time when Town was only a Midland League team. Of interest here is the mention in the third paragraph of 'The Redskins' which MUST be Town because Howard - who kicks clear - is a Town player; so does this prove that Town played in red at this time? All Town fans know that we were at one time known as 'The Scarlet Runners' due to playing in red shirts - later to become pink as the colour ran after all too-frequent washes! - and this would appear to be the evidence that was required. This brilliant piece of history is glued to the back of the telegram that I have announcing Town's acceptance into the Football League soon after in 1910. -

Sample Download

David Stuart & RobertScotland: Club, Marshall Country & Collectables Club, Country & Collectables 1 Scotland Club, Country & Collectables David Stuart & Robert Marshall Pitch Publishing Ltd A2 Yeoman Gate Yeoman Way Durrington BN13 3QZ Email: [email protected] Web: www.pitchpublishing.co.uk First published by Pitch Publishing 2019 Text © 2019 Robert Marshall and David Stuart Robert Marshall and David Stuart have asserted their rights in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 to be identified as the authors of this work. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission in writing of the publisher and the copyright owners, or as expressly permitted by law, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organization. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the terms stated here should be sent to the publishers at the UK address printed on this page. The publisher makes no representation, express or implied, with regard to the accuracy of the information contained in this book and cannot accept any legal responsibility for any errors or omissions that may be made. A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. 13-digit ISBN: 9781785315419 Design and typesetting by Olner Pro Sport Media. Printed in India by Replika Press Scotland: Club, Country & Collectables INTRODUCTION Just when you thought it was safe again to and Don Hutchison, the match go back inside a quality bookshop, along badges (stinking or otherwise), comes another offbeat soccer hardback (or the Caribbean postage stamps football annual for grown-ups) from David ‘deifying’ Scotland World Cup Stuart and Robert Marshall, Scottish football squads and the replica strips which writing’s answer to Ernest Hemingway and just defy belief! There’s no limit Mary Shelley. -

Book of Condolences

Book of Condolences Ewan Constable RIP JIM xx Thanks for the best childhood memories and pu;ng Dundee United on the footballing map. Ronnie Paterson Thanks for the memories of my youth. Thoughts are with your family. R I P Thank you for all the memoires, you gave me so much happiness when I was growing up. You were someone I looked up to and admired Those days going along to Tanadice were fantasEc, the best were European nights Aaron Bernard under the floodlights and seeing such great European teams come here usually we seen them off. Then winning the league and cups, I know appreciate what an achievement it was and it was all down to you So thank you, you made a young laddie so happy may you be at peace now and free from that horrible condiEon Started following United around 8 years old (1979) so I grew up through Uniteds glory years never even realised Neil smith where the success came from I just thought it was the norm but it wasn’t unEl I got a bit older that i realised that you were the reason behind it all Thank you RIP MR DUNDEE UNITED � � � � � � � � Michael I was an honour to meet u Jim ur a legend and will always will be rest easy jim xxx� � � � � � � � First of all. My condolences to Mr. McLean's family. I was fortunate enough to see Dundee United win all major trophies And it was all down to your vision of how you wanted to play and the kind of players you wanted for Roger Keane Dundee United. -

Glasgow: in a League of Its Own

ESTABLISHED IN 1863 Volume 148, No. 7 March 2011 Glasgow: In a League of Its Own Inside this Issue BY JONATHAN CLEGG Feature Article………….1 English football is dominated by Scottish managers, and from one city in particular Message from our President…................2 GLASGOW, Scotland—There are some 240 overseas players in the English Pre- mier League. They're spread all over the map—35 from France, seven from Senegal, Upcoming Events…….....3 one each from Uruguay, Mali and Greece. By some measures, it's the most cosmopoli- Tartan Ball flyer ………..6 tan league in all of sports. But when it comes to the men prowling the sidelines, some of the very best come from this same cold, industrial city of 600,000 in western Scot- Gifts to the Society: Mem- land. bership Announce- ments…………….....7 Hear ye, Hear Ye: Notice of motion to be voted on by the membership …………………......7 Dunsmuir Scottish Danc- ers flyer…………….8 Dan Reid Memorial Chal- lenge Recital flyer….9 Press Association—Birmingham City manager Alex McLeish, left, shakes hands with Alex Fergu- son of Manchester United. Both men were raised in Glasgow. (Continued on page 4) March 2011 www.saintandrewssociety-sf.org Page 1 A Message from Our President The Saint Andrew's Dear Members and Society Society of San Francisco Friends: 1088 Green Street San Francisco, CA Our February meeting went well. 94133‐3604 (415) 885‐6644 Second VP David McCrossan served Editor: William Jaggers some excellent pizzas and fresh green Email: [email protected] salad, then entertained and informed Membership Meetings: us with a first class presentation on Meetings are held the the ‚Languages of Scotland.‛ He 3rd Monday of the month, at showed some great film clips, too. -

Trevor Cherry

Wednesday 13 May 2020 GUERNSEY PRESS OBITUARY 23 OBITUARY Trevor Cherry by Advocate Footballer Trevor Raymond Ashton Cherry, pictured in 1981. (28247216) T IS WITH regret that I have learnt of the sad demise of my friend Trevor Cherry as a result of a massive heart attack. This makes it two former footballers who have died within a Ishort period of time. Trevor was in the same school year as myself and over the years we had become friends and only about six weeks ago my other half was with the denizens of the chairman’s suite at City in Madrid, of which Trevor was part, as a result of his friendship and business association with Mike Marshall (himself a former player). Trevor had been a regular visitor over the years to City and always had time to talk about his former colleagues at Elland Road. Indeed, I had hoped many years ago during the second coming of Malcolm Allison to persuade him to join City to give the defence more stability. Before going into detail I must say that he was a very self-effacing and modest man, unlike most footballers. There will be many tributes to Trevor but when Bradford City went into administration in the early 1980s Stafford Higginbottom, later chairman, said to me that unlike many managers he had a brain (and not just in his feet) and was very sensiblel. Prophetic words, it proved. Trevor was born in Huddersfield and was always very proud of the town (and had heard of the world-famous Choral Society) and eventually forced his way into the first team. -

Brian Clough and Peter Taylor

Made in Derby 2018 Profile Brian Clough and Peter Taylor Brian Clough and Peter Taylor. Two names that will always be associated with Derby County. They met as young players – Brian a centre-forward and Peter a goalkeeper – at Middlesbrough FC, where they played together for six years. With a shared passion for the beautiful game they formed a friendship that would take them to the very top of English and European football. They first joined forces as managers at Hartlepool United but it was at Derby County where the dynamic duo, as they were known, had their first taste of the big time. Many of Derby's greatest names were signed in the Clough-Taylor era: Roy McFarland, John O'Hare, Alan Hinton, John McGovern, Willie Carlin, Dave Mackay, Colin Todd and Archie Gemmill to name a few. The two managers and their magnificent team took the Rams to the very top, winning the Division One Championship in 1972 and reaching the European Cup semi-finals. The pair controversially resigned early in the 1973-74 season and the partnership broke up briefly, only be reunited at Nottingham Forest in 1976 where they won many accolades, including two European Cups. But it was at Derby County where the partnership first flourished and Taylor’s daughter, Wendy Dickinson, in a biography of her father, said: “When dad and Brian arrived at the Baseball Ground in May, 1967 it was as if Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid had ridden into town, all guns blazing. These two bright young upstarts were a breath of fresh air at a club that was stuck in the past.” She said her dad was “passionate” about managing Derby and added: “My mum remembers driving down to Derby for the first time and dad said, ‘I wonder what the supporters are like?’ He later said he thought they were the best in the country.” The success of that Derby County team affected everyone in the town and amazing results week after week sent people to work on a Monday morning with a spring in their step. -

CONFERENCE and EVENTS a Signature Venue for Your Event WELCOME to LEEDS UNITED HIRES REQUIRED FOOTBALL CLUB, a SIGNATURE VENUE for YOUR EVENT

LEEDS UNITED FOOTBALL CLUB CONFERENCE AND EVENTS A signature venue for your event WELCOME TO LEEDS UNITED HIRES REQUIRED FOOTBALL CLUB, A SIGNATURE VENUE FOR YOUR EVENT. One of the UK’s leading Conference & Events venues and We can cater for: the home of Leeds United Football Club; our passion on the pitch is matched by the passion of our world class Conferences, Meetings & AGM’s Product Launches Conference & Events Team off the pitch. Gala Dinners Training At Elland Road we are able to host a With over 100 years combined Award Ceremonies Interviews wide range of events, from sell-out pop experience, our dedicated, award concerts inside the stadium, to private winning team will take care of every Christmas Parties Networking Events one-to-one business meeting - we can detail, providing support and expertise cater for your every need. throughout the planning Exhibitions Car Launches and delivery. Fashion Shows Pitch Events Private Celebrations Sporting Events To find out more please call our dedicated events team: Weddings Team Building 0871 334 1919 (OPTION 2) or email: [email protected] Asian Weddings Proms To find out more please call our dedicated events team: 0871 334 1919 (OPTION 2) or email: [email protected] 02/03 - Conference and Events The Centenary Pavilion provides one of the biggest WELCOME TO THE Conference & Events spaces in the North of England - CENTENARY PAVILION with over 2000 square metres of space. Purpose built, provides With a clear span, it’s the perfect venue exhibitions, to live music, fashion and for product launches, exhibitions and sporting events’. -

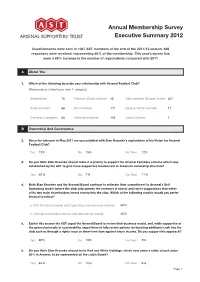

Annual Membership Survey Executive Summary 2012

Annual Membership Survey Executive Summary 2012 Questionnaires were sent to 1067 AST members at the end of the 2011/12 season. 636 responses were received, representing 60% of the membership. This year’s survey has seen a 65% increase in the number of respondents compared with 2011 A About You 1. Which of the following describe your relationship with Arsenal Football Club? (Respondents ticked more than 1 category) Shareholder:70 Platinum (Club) member:45 Gold member (Season ticket): 301 Silver member:66 Red member:171 Away scheme member: 17 Overseas supporter:60 Fanshare member:105 Junior Gunner: 1 B Ownership And Governance 2. Since his takeover in May 2011 are you satisfi ed with Stan Kroenke’s explanation of his Vision for Arsenal Football Club? Yes: 13%No: 75% No View: 12% 3. Do you think Stan Kroenke should make it a priority to support the Arsenal Fanshare scheme which was established by the AST to give more supporters involvement in Arsenal’s ownership structure? Yes: 82%No: 7% No View: 11% 4. Both Stan Kroenke and the Arsenal Board continue to reiterate their commitment to Arsenal’s Self- Sustaining model (where the club only spends the revenues it raises) and reject suggestions that either of its two main shareholders invest money into the club. Which of the following models would you prefer Arsenal to follow? a. Self-Sustaining model (only spending club revenues earned) 60% b. Outside investment into the club (benefactor model) 40% 5. Earlier this season the AST urged the Arsenal Board to review their business model, and, while supportive of the general principle of sustainability, urged them to fully review options for injecting additional cash into the club such as through a rights issue or short-term loan against future income.