Religious Factors; *Student Attitudes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

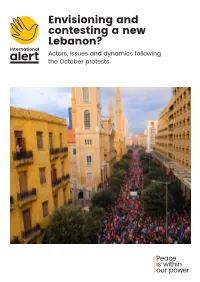

Envisioning and Contesting a New Lebanon? Actors, Issues and Dynamics Following the October Protests About International Alert

Envisioning and contesting a new Lebanon? Actors, issues and dynamics following the October protests About International Alert International Alert works with people directly affected by conflict to build lasting peace. We focus on solving the root causes of conflict, bringing together people from across divides. From the grassroots to policy level, we come together to build everyday peace. Peace is just as much about communities living together, side by side, and resolving their differences without resorting to violence, as it is about people signing a treaty or laying down their arms. That is why we believe that we all have a role to play in building a more peaceful future. www.international-alert.org © International Alert 2020 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without full attribution. Layout: Marc Rechdane Front cover image: © Ali Hamouch Envisioning and contesting a new Lebanon? Actors, issues and dynamics following the October protests Muzna Al-Masri, Zeina Abla and Rana Hassan August 2020 2 | International Alert Envisioning and contesting a new Lebanon? Acknowledgements International Alert would like to thank the research team: Muzna Al-Masri, Zeina Abla and Rana Hassan, as well as Aseel Naamani, Ruth Simpson and Ilina Slavova from International Alert for their review and input. We are also grateful for the continuing support from our key funding partners: the Dutch Ministry of Foreign Affairs; the Irish Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade; and the Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency. -

Iraq's Evolving Insurgency

CSIS _______________________________ Center for Strategic and International Studies 1800 K Street N.W. Washington, DC 20006 (202) 775 -3270 Access: Web: CSIS.ORG Contact the Author: [email protected] Iraq’s Evolving Insurgency Anthony H. Cordesman Center for Strategic and International Studies With the Assistance of Patrick Baetjer Working Draft: Updated as of August 5, 2005 Please not e that this is part of a rough working draft of a CSIS book that will be published by Praeger in the fall of 2005. It is being circulated to solicit comments and additional data, and will be steadily revised and updated over time. Copyright CSIS, all rights reserved. All further dissemination and reproduction must be done with the written permission of the CSIS Cordesman: Iraq’s Evolving Insurgency 8/5/05 Page ii I. INTR ODUCTION ................................ ................................ ................................ ................................ ..... 1 SADDAM HUSSEIN ’S “P OWDER KEG ” ................................ ................................ ................................ ......... 1 AMERICA ’S STRATEGIC MISTAKES ................................ ................................ ................................ ............. 2 AMERICA ’S STRATEGIC MISTAKES ................................ ................................ ................................ ............. 6 II. THE GROWTH AND C HARACTER OF THE INSURGENT THREA T ................................ ........ 9 DENIAL AS A METHOD OF COUNTER -INSURGENCY WARFARE ............................... -

Political Leadership in Lebanon and the Jumblatt Phenomenon: Tipping the Scales of Lebanese Politics Sebastian Gerlach

SAIS EUROPE JOURNAL OF GLOBAL AFFAIRS Political Leadership in Lebanon and the Jumblatt Phenomenon: Tipping the Scales of Lebanese Politics Sebastian Gerlach For observers and scholars of contemporary Lebanese politics, an understanding of Lebanon’s complex political dynamics is hardly possible without a thorough analysis of the role of Walid Jumblatt, the leader of the country’s Druze community. Notwithstanding his sect’s marginal size, Jumblatt has for almost four decades greatly determined the course of domestic developments. Particularly between 2000 and 2013, the Druze leader developed into a local kingmaker through his repeated switch in affiliations between Lebanon’s pro- and anti-Syrian coalitions. This study argues that Jumblatt’s political behavior during this important period in recent Lebanese history was driven by his determination to ensure the political survival of his Druze minority community. Moreover, it highlights that Jumblatt’s ongoing command over the community, which appears to be impressive given his frequent political realignments, stems from his position as the dominating, traditional Druze za’im and because the minority community recognized his political maneuvering as the best mean to provide the Druze with relevance in Lebanon’s political arena. 84 VOLUME 20 INTRODUCTION who failed to preserve their follower- ship after altering their political ori- For observers and scholars of con- 2 temporary Lebanese politics, a thor- entation. In this respect, it is even ough understanding of the country’s more puzzling that Jumblatt was able complex political dynamics is hardly to maintain the support of his Druze possible without analyzing the role of community, known for its nega- Walid Jumblatt, the leader of Leba- tive attitudes towards the prominent non’s Druze community. -

Emirado Do Monte Líbano, Passando Pelo Mandato Francês, Até a Criação Do «Grande Líbano», Bem Como Uma Reflexão Sobre Seus Dilemas Contemporâneos

29 • Conjuntura Internacional • Belo Horizonte, ISSN 1809-6182, v.17 n.2, p.29 - 47, ago. 2020 29 • Conjuntura Internacional • Belo Horizonte, ISSN 1809-6182, v.17 n.2, p.29 - 47, ago. 2020 Artigo Do Pequeno ao Grande Líbano: os desafios contemporâneos da República Libanesa From Small to Greater Lebanon: the contemporary challenges of the Lebanese Republic Del Pequeño al Gran Líbano: los desafios contemporáneos de la República Libanesa Danny Zahreddine1 DOI: 10.5752/P.1809-6182.2020v17n2p29 Recebido em: 15 de julho de 2020 Aceito em: 27 de agosto de 2020 Resumo Marcado por uma história de múltiplos conflitos internos, e de intervenções externas, a República Libanesa é o resultado de decisões pretéritas que foram fundamentais na deter- minação dos seus dilemas atuais. Este artigo apresenta uma análise histórica da criação do Líbano, desde a formação do Emirado do Monte Líbano, passando pelo mandato francês, até a criação do «Grande Líbano», bem como uma reflexão sobre seus dilemas contemporâneos. Palavras-chave: Líbano. Minorias Religiosas. Guerra Civil. Abstract Marked by a history of multiple internal conflicts and external interventions, the Lebanese Republic is the result of past decisions that were fundamental in determining its current dilemmas. This article presents a historical analysis of the creation of Lebanon, from the formation of the Emirate of Mount Lebanon, through the French mandate, until the crea- tion of “Greater Lebanon”, as well as a reflection on its contemporary dilemmas. Keywords: Lebanon. Religious Minorities. Civil war. Resumen Marcada por una historia de múltiples conflictos internos e intervenciones externas, la República Libanesa es el resultado de decisiones pasadas que fueron fundamentales para determinar sus dilemas actuales. -

CRS Issue Brief for Congress Received Through the CRS Web

Order Code IB89118 CRS Issue Brief for Congress Received through the CRS Web Lebanon Updated March 16, 2005 Clyde R. Mark Foreign Affairs, Defense, and Trade Division Congressional Research Service ˜ The Library of Congress CONTENTS SUMMARY MOST RECENT DEVELOPMENTS BACKGROUND AND ANALYSIS United States and Lebanon U.S.-Lebanon Issues The Syrian Presence Peace Process Lebanon-Israel Border Clashes The Travel Ban U.S. Interests U.S. Policy Toward Lebanon U.S. Assistance for Lebanon Other Events in U.S.-Lebanon Relations Role of Congress Lebanon’s Political Profile Civil War, 1975-1990 The “Taif” Reforms, 1989 Political Dynamics Lebanon’s Population 1992, 1996, and 2000 Elections Foreign Presence in Lebanon Syria Israel CHRONOLOGY IB89118 03-16-05 Lebanon SUMMARY The United States and Lebanon continue cupy the northern and eastern parts of the to enjoy good relations. Prominent current country. Israeli forces invaded southern Leba- issues between the United States and Lebanon non in 1982 and occupied a 10-mile-wide strip include progress toward a Lebanon-Israel along the Israel-Lebanon border until May 23, peace treaty, U.S. aid to Lebanon, and Leba- 2000. non’s capacity to stop Hizballah militia at- tacks on Israel. The United States supports Lebanon’s government is based in part Lebanon’s independence and favored the end on a 1943 agreement that called for a of Israeli and Syrian occupation of parts of Maronite Christian President, a Sunni Muslim Lebanon. Israel withdrew from southern Prime Minister, and a Shia Muslim Speaker of Lebanon on May 23, 2000, and three recent the National Assembly, and stipulated that the withdrawals have reduced the Syrian military National Assembly seats and civil service jobs presence from 30,000 to 16,000. -

WARS and WOES a Chronicle of Lebanese Violence1

The Levantine Review Volume 1 Number 1 (Spring 2012) OF WARS AND WOES A Chronicle of Lebanese Violence1 Mordechai Nisan* In the subconscious of most Lebanese is the prevalent notion—and the common acceptance of it—that the Maronites are the “head” of the country. ‘Head’ carries here a double meaning: the conscious thinking faculty to animate and guide affairs, and the locus of power at the summit of political office. While this statement might seem outrageous to those unversed in the intricacies of Lebanese history and its recent political transformations, its veracity is confirmed by Lebanon’s spiritual mysteries, the political snarls and brinkmanship that have defined its modern existence, and the pluralistic ethno-religious tapestry that still dominates its demographic makeup. Lebanon’s politics are a clear representation of, and a response to, this seminal truth. The establishment of modern Lebanon in 1920 was the political handiwork of Maronites—perhaps most notable among them the community’s Patriarch, Elias Peter Hoyek (1843-1931), and public intellectual and founder of the Alliance Libanaise, Daoud Amoun (1867-1922).2 In recognition of this debt, the President of the Lebanese Republic has by tradition been always a Maronite; the country’s intellectual, cultural, and political elites have hailed largely from the ranks of the Maronite community; and the Patriarch of the Maronite Church in Bkirke has traditionally held sway as chief spiritual and moral figure in the ceremonial and public conduct of state affairs. In the unicameral Lebanese legislature, the population decline of the Christians as a whole— Maronites, Greek Orthodox, Catholics, and Armenians alike—has not altered the reality of the Maronites’ pre-eminence; equal confessional parliamentary representation, granting Lebanon’s Christians numerical parity with Muslims, still defines the country’s political conventions. -

November 04, 1957 Mounting a Coup D'état in Lebanon

Digital Archive digitalarchive.wilsoncenter.org International History Declassified November 04, 1957 Mounting a Coup d’État in Lebanon Citation: “Mounting a Coup d’État in Lebanon,” November 04, 1957, History and Public Policy Program Digital Archive, Emir Farid Chehab Collection, GB165-0384, Box 13, File 160/13, Middle East Centre Archive, St Antony’s College, Oxford. https://digitalarchive.wilsoncenter.org/document/176106 Summary: Account of plans and objectives for a coup in Lebanon. Credits: This document was made possible with support from Youmna and Tony Asseily. Original Language: Arabic Contents: English Translation Scan of Original Document 160/13 4/11/1957 Mounting a coup d’état in Lebanon The first phase: Organising a popular festival in the suburbs of Beirut. The location has not been decided upon yet, but they are thinking of Ghadir (which belongs to the Salam family). Clashing with the security forces. Leaders seeking refuge in al-Mukhtara, Baalbeik, or Hermel. Declaring a rebellion against the Government. Announcing the formation of the Government of Free Lebanon and informing the Army Command, security forces, government departments, and all employees about the new government's policies which can be summarised as follows: Dissolution of the National Assembly. Dismissing the President of the Republic and putting him on trial. Dismissing the Government and putting its members on trial. Establishing revolutionary courts in the areas under their control. Communists and opposition supporters will launch mass demonstrations in support of the Revolutionary Government in the Lebanese capital and towns. Egypt, Syria, and communist supporters are behind this move, which counts on the assistance of: Ahmad al-As'ad - Sabri Hamadeh - Kamal Jumblatt - Hamid Franjieh's group - Hachem al-Husseini - Rachid Karami - Maarouf Saad - Sa'eb Salam – and Abdullah al-Yafi. -

Political Party Mapping in Lebanon Ahead of the 2018 Elections

Political Party Mapping in Lebanon Ahead of the 2018 Elections Foreword This study on the political party mapping in Lebanon ahead of the 2018 elections includes a survey of most Lebanese political parties; especially those that currently have or previously had parliamentary or government representation, with the exception of Lebanese Communist Party, Islamic Unification Movement, Union of Working People’s Forces, since they either have candidates for elections or had previously had candidates for elections before the final list was out from the Ministry of Interior and Municipalities. The first part includes a systematic presentation of 27 political parties, organizations or movements, showing their official name, logo, establishment, leader, leading committee, regional and local alliances and relations, their stance on the electoral law and their most prominent candidates for the upcoming parliamentary elections. The second part provides the distribution of partisan and political powers over the 15 electoral districts set in the law governing the elections of May 6, 2018. It also offers basic information related to each district: the number of voters, the expected participation rate, the electoral quotient, the candidate’s ceiling on election expenditure, in addition to an analytical overview of the 2005 and 2009 elections, their results and alliances. The distribution of parties for 2018 is based on the research team’s analysis and estimates from different sources. 2 Table of Contents Page Introduction ....................................................................................................... -

European Union Election Observation Mission to the Republic of Lebanon 2018 EU Election Observation Mission – Lebanon 2018 FINAL REPORT

Parliamentary Elections 2018 European Union Election Observation Mission to the Republic of Lebanon 2018 EU Election Observation Mission – Lebanon 2018 FINAL REPORT LEBANON FINAL REPORT Parliamentary elections 2018 EUROPEAN UNION ELECTION OBSERVATION MISSION www.eueom-lebanon2018.eu This report has been produced by the European Union Election Observation Mission (EU EOM) to Lebanon 2018 and contains the conclusions of its observation of the parliamentary elections on 6 May. The contents of this report do not necessarily reflect the official position of the European Union. 1 EU Election Observation Mission – Lebanon 2018 FINAL REPORT Table of Contents I. Executive summary ................................................................................................. 3 II. Introduction ........................................................................................................... 8 III. Political background ............................................................................................... 9 IV. Implementation of previous EOM recommendations ............................................ 10 V. Legal framework ................................................................................................... 11 VI. Election Administration ........................................................................................ 14 VII. Voter registration ................................................................................................. 17 VIII. Registration of candidates and political parties .................................................... -

Country Advice Lebanon Lebanon – LBN37789 – Lebanese Forces

Country Advice Lebanon Lebanon – LBN37789 – Lebanese Forces political party – Confessional system 1 December 2010 1. Please send some general information on the Lebanese Forces political party, including who were their leaders and/or important milestones since 1994. Please include any information you feel may be useful. Background The Lebanese Forces political party formed as a mainly Maronite Christian military coalition during the civil war between Christian, Muslim and Druze militias between 1975 and 1990. The Lebanese Forces was one of the strongest parties to the conflict, during which time it controlled mainly-Christian East Beirut and areas north of the capital. In 1982, during the civil war, a key figure in the Lebanese Forces, Bashir Gemayel, who was the then President of Lebanon, was killed. The Lebanese Forces was regularly accused of politically-motivated killings and arrests and other serious human rights abuses before the war ended in 1990, although other factions in the conflict were accused of similar abuses. The Phalangists, the largest militia in the Lebanese Forces, massacred hundreds of civilians in the Sabra and Shatila refugee camps in 1982. The anti-Syrian Lebanese Forces was banned in 1994, but remained influential among the 800,000-strong Maronite Christian community that dominated Lebanon before the war.1 While the Lebanese Forces has perpetrated human rights abuses, a 2004 Amnesty International report stated that “Samir Gea'gea and Jirjis al-Khouri, like scores of other LF members, may have been victims of human -

The Hariri Assassination and the Making of a Usable Past for Lebanon

LOCKED IN TIME ?: THE HARIRI ASSASSINATION AND THE MAKING OF A USABLE PAST FOR LEBANON Jonathan Herny van Melle A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS May 2009 Committee: Dr. Sridevi Menon, Advisor Dr. Neil A. Englehart ii ABSTRACT Dr. Sridevi Menon, Advisor Why is it that on one hand Lebanon is represented as the “Switzerland of the Middle East,” a progressive and prosperous country, and its capital Beirut as the “Paris of the Middle East,” while on the other hand, Lebanon and Beirut are represented as sites of violence, danger, and state failure? Furthermore, why is it that the latter representation is currently the pervasive image of Lebanon? This thesis examines these competing images of Lebanon by focusing on Lebanon’s past and the ways in which various “pasts” have been used to explain the realities confronting Lebanon. To understand the contexts that frame the two different representations of Lebanon I analyze several key periods and events in Lebanon’s history that have contributed to these representations. I examine the ways in which the representation of Lebanon and Beirut as sites of violence have been shaped by the long period of civil war (1975-1990) whereas an alternate image of a cosmopolitan Lebanon emerges during the period of reconstruction and economic revival as well as relative peace between 1990 and 2005. In juxtaposing the civil war and the assassination of former Lebanese Prime Minister Rafic Hariri in Beirut on February 14, 2005, I point to the resilience of Lebanon’s civil war past in shaping both Lebanese and Western memories and understandings of the Lebanese state. -

Lebanon's Legacy of Political Violence

LEBANON Lebanon’s Legacy of Political Violence A Mapping of Serious Violations of International Human Rights and Humanitarian Law in Lebanon, 1975–2008 September 2013 International Center Lebanon’s Legacy of Political Violence for Transitional Justice Acknowledgments The Lebanon Mapping Team comprised Lynn Maalouf, senior researcher at the Memory Interdisciplinary Research Unit of the Center for the Study of the Modern Arab World (CEMAM); Luc Coté, expert on mapping projects and fact-finding commissions; Théo Boudruche, international human rights and humanitarian law consultant; and researchers Wajih Abi Azar, Hassan Abbas, Samar Abou Zeid, Nassib Khoury, Romy Nasr, and Tarek Zeineddine. The team would like to thank the committee members who reviewed the report on behalf of the university: Christophe Varin, CEMAM director, who led the process of setting up and coordinating the committee’s work; Annie Tabet, professor of sociology; Carla Eddé, head of the history and international relations department; Liliane Kfoury, head of UIR; and Marie-Claude Najm, professor of law and political science. The team extends its special thanks to Dima de Clerck, who generously shared the results of her fieldwork from her PhD thesis, “Mémoires en conflit dans le Liban d’après-guerre: le cas des druzes et des chrétiens du Sud du Mont-Liban.” The team further owes its warm gratitude to the ICTJ Beirut office team, particularly Carmen Abou Hassoun Jaoudé, Head of the Lebanon Program. ICTJ thanks the European Union for their support which made this project possible. International Center for Transitional Justice The International Center for Transitional Justice (ICTJ) works to redress and prevent the most severe violations of human rights by confronting legacies of mass abuse.