Chris Thile, the Punch Brothers, and the Negotiation of Genre

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

FACULTY Fl FAMOUS

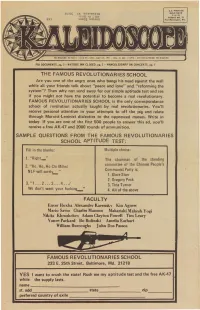

U.S. POSTAGE BULK RATE zoz<z$ I ft '993fHBMTTW PAID °^yi *a ^t8T PERMIT NO. 33 uomxS uopaoo Port Washington, Wis. FBI DOCUMENTS, pg. 3 + WAYSIDE INN CLOSED, pg. 2 + MANGELSDORFF ON CONCERTS, pg. 7 I THE FAMOUS REVOLUTIONARIES SCHOOL Are you one of the angry ones who bangs his nead against the wall while all your friends talk about "peace and love" and "reforming the system"? Then why not send away for our simple aptitude test and see if you might not have the potential to become a real revolutionary. FAMOUS REVOLUTIONARIES SCHOOL | the only correspondance school of revolution actually taught by real revolutionaries. You'll receive personal attention in your attempts to off the pig and relate through Marxist-Leninist dialectics to the oppreseed masses. Write in today. If you are one of the first 500 people to answer this ad, you'll receive a free AK-47 and 2000 rounds of ammunition. SAMPLE QUESTIONS FROM THE FAMOUS REVOLUTIONARIES SCHOOL APTITUDE TEST: Fill in the blanks: Multiple choise: a 1. "Right, The chairman of the standing committee of the Chinese People's 2. "Ho, Ho, Ho Chi Mihn/ NLF will surely" Jj|§ Communist Party is; « 1. Blaze Starr | 2. Gregory Peck 3."1 ... 2 ... 3 ... 4.../ 3. Tina Turner II We don't want your fucking 4. All of the above FACULTY fL Enver Hoxha Alexander Karenskv Kin Agnew Mario Savio Charles Manson Maharishi Mahesh Yogi Nikita Khrushchev Adam Clayton Powell Tim Leary Vance Packard Bo Bolinski Amelia Earhart William Burroughs John Dos Passos &u FAMOUS REVOLUTIONARIES SCHOOL 233 E. -

Nickel Creek a Dotted Line Mp3, Flac, Wma

Nickel Creek A Dotted Line mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Folk, World, & Country Album: A Dotted Line Country: Europe Released: 2014 Style: Bluegrass MP3 version RAR size: 1513 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1105 mb WMA version RAR size: 1926 mb Rating: 4.1 Votes: 282 Other Formats: DTS XM DMF FLAC TTA MP3 AUD Tracklist Hide Credits Rest Of My Life A1 3:40 Lyrics By – Chris ThileMusic By – Chris Thile, Sara Watkins, Sean Watkins Destination A2 3:51 Lyrics By – Sara WatkinsMusic By – Chris Thile, Sara Watkins, Sean Watkins Elsie A3 2:33 Written-By – Chris Thile Christmas Eve A4 4:23 Lyrics By – Sara WatkinsMusic By – Chris Thile, Sara Watkins, Sean Watkins Hayloft A5 3:18 Written-By – Ryan Guldemond 21st Of May B1 2:47 Written-By – Sean Watkins Love Of Mine B2 4:42 Lyrics By – Chris ThileMusic By – Chris Thile, Sara Watkins, Sean Watkins Elephant In The Corn B3 5:10 Written-By – Chris Thile, Sara Watkins, Sean Watkins You Don't Know What's Going On B4 2:50 Lyrics By – Chris ThileMusic By – Chris Thile, Sara Watkins, Sean Watkins Where Is Love Now B5 4:44 Written-By – Sam Phillips Credits Bass – Mark Schatz Bass [Bowed] – Edgar Meyer Design – Evan Gaffney Design Engineer – Cian Riordan, Eric Valentine Engineer [Assisted By] – Justin Long Fiddle – Sara Watkins Guitar – Sean Watkins Management – Q Prime South, Red Light Management Mandolin, Bouzouki – Chris Thile Mastered By – Eric Valentine Mixed By – Eric Valentine Percussion – Eric Valentine, Matt Chamberlain Photography [Cover] – Underwood Photography Archives Photography -

Ross Nickerson-Banjoroadshow

Pinecastle Recording Artist Ross Nickerson Ross’s current release with Pin- ecastle, Blazing the West, was named as “One of the Top Ten CD’s of 2003” by Country Music Television, True West Magazine named it, “Best Bluegrass CD of 2003” and Blazing the West was among the top 15 in ballot voting for the IBMA Instrumental CD of the Year in 2003. Ross Nickerson was selected to perform at the 4th Annual Johnny Keenan Banjo Festival in Ireland this year headlined by Bela Fleck and Earl Scruggs last year. Ross has also appeared with the New Grass Revival, Hot Rize, Riders in the Sky, Del McCoury Band, The Oak Ridge Boys, Nitty Gritty Dirt Band and has also picked and appeared with some of the best banjo players in the world including Earl Scruggs, Bela Fleck, Bill Keith, Tony Trischka, Alan Munde, Doug Dillard, Pete Seeger and Ralph Stanley. Ross is a full time musician and on the road 10 to 15 days a month doing concerts , workshops and expanding his audience. Ross has most recently toured England, Ireland, Germany, Holland, Sweden and visited 31 states and Canada in 2005. Ross is hard at work writing new material for the band and planning a new CD of straight ahead bluegrass. Ross is the author of The Banjo Encyclopedia, just published by Mel Bay Publications in October 2003 which has already sold out it’s first printing. For booking information contact: Bullet Proof Productions 1-866-322-6567 www.rossnickerson.com www.banjoteacher.com [email protected] BLAZING THE WEST ROSS NICKERSON 1. -

A Film by Chris Hegedus and D a Pennebaker

a film by Chris Hegedus and D A Pennebaker 84 minutes, 2010 National Media Contact Julia Pacetti JMP Verdant Communications [email protected] (917) 584-7846 FIRST RUN FEATURES The Film Center Building, 630 Ninth Ave. #1213 New York, NY 10036 (212) 243-0600 Fax (212) 989-7649 Website: www.firstrunfeatures.com Email: [email protected] PRAISE FOR KINGS OF PASTRY “The film builds in interest and intrigue as it goes along…You’ll be surprised by how devastating the collapse of a chocolate tower can be.” –Mike Hale, The New York Times Critic’s Pick! “Alluring, irresistible…Everything these men make…looks so mouth-watering that no one should dare watch this film on even a half-empty stomach.” – Kenneth Turan, Los Angeles Times “As the helmers observe the mental, physical and emotional toll the competition exacts on the contestants and their families, the film becomes gripping, even for non-foodies…As their calm camera glides over the chefs' almost-too-beautiful-to-eat creations, viewers share their awe.” – Alissa Simon, Variety “How sweet it is!...Call it the ultimate sugar high.” – VA Musetto, The New York Post “Gripping” – Jay Weston, The Huffington Post “Chris Hegedus and D.A. Pennebaker turn to the highest levels of professional cooking in Kings of Pastry,” a short work whose drama plays like a higher-stakes version of popular cuisine-oriented reality TV shows.” – John DeFore, The Hollywood Reporter “A delectable new documentary…spellbinding demonstrations of pastry-making brilliance, high drama and even light moments of humor.” – Monica Eng, The Chicago Tribune “More substantial than any TV food show…the antidote to Gordon Ramsay.” – Andrea Gronvall, Chicago Reader “This doc is a demonstration that the basics, when done by masters, can be very tasty.” - Hank Sartin, Time Out Chicago “Chris Hegedus and D.A. -

Bluegrass Outlet Banjo Tab List Sale

ORDER FORM BANJO TAB LIST BLUEGRASS OUTLET Order Song Title Artist Notes Recorded Source Price Dixieland For Me Aaron McDaris 1st Break Larry Stephenson "Clinch Mountain Mystery" $2 I've Lived A Lot In My Time Aaron McDaris Break Larry Stephenson "Life Stories" $2 Looking For The Light Aaron McDaris Break Aaron McDaris "First Time Around" $2 My Home Is Across The Blueridge Mtns Aaron McDaris 1st Break Mashville Brigade $2 My Home Is Across The Blueridge Mtns Aaron McDaris 2nd Break Mashville Brigade $2 Over Yonder In The Graveyard Aaron McDaris 1st Break Aaron McDaris "First Time Around" $2 Over Yonder In The Graveyard Aaron McDaris 2nd Break Aaron McDaris "First Time Around" $2 Philadelphia Lawyer Aaron McDaris 1st Break Aaron McDaris "First Time Around" $2 When My Blue Moon Turns To Gold Again Aaron McDaris Intro & B/U 1st verse Aaron McDaris "First Time Around" $2 Leaving Adam Poindexter 1st Break James King Band "You Tube" $2 Chatanoga Dog Alan Munde Break C-tuning Jimmy Martin "I'd Like To Be 16 Again" $2 Old Timey Risin' Damp Alan O'Bryant Break Nashville Bluegrass Band "Idle Time" $4 Will You Be Leaving Alison Brown 1st Break Alison Kraus "I've Got That Old Feeling" $2 In The Gravel Yard Barry Abernathy Break Doyle Lawson & Quicksilver "Never Walk Away" $2 Cold On The Shoulder Bela Fleck Break Tony Rice "Cold On The Shoulder" $2 Pain In My Heart Bela Fleck 1st Break Live Show Rockygrass Colorado 2012 $2 Pain In My Heart Bela Fleck 2nd Break Live Show Rockygrass Colorado 2012 $2 The Likes Of Me Bela Fleck Break Tony Rice "Cold On -

Songwriter Mike O'reilly

Interviews with: Melissa Sherman Lynn Russwurm Mike O’Reilly, Are You A Bluegrass Songwriter? Volume 8 Issue 3 July 2014 www.bluegrasscanada.ca TABLE OF CONTENTS BMAC EXECUTIVE President’s Message 1 President Denis 705-776-7754 Chadbourn Editor’s Message 2 Vice Dave Porter 613-721-0535 Canadian Songwriters/US Bands 3 President Interview with Lynn Russworm 13 Secretary Leann Music on the East Coast by Jerry Murphy 16 Chadbourn Ode To Bill Monroe 17 Treasurer Rolly Aucoin 905-635-1818 Open Mike 18 Interview with Mike O’Reilly 19 Interview with Melissa Sherman 21 Songwriting Rant 24 Music “Biz” by Gary Hubbard 25 DIRECTORS Political Correctness Rant - Bob Cherry 26 R.I.P. John Renne 27 Elaine Bouchard (MOBS) Organizational Member Listing 29 Gord Devries 519-668-0418 Advertising Rates 30 Murray Hale 705-472-2217 Mike Kirley 519-613-4975 Sue Malcom 604-215-276 Wilson Moore 902-667-9629 Jerry Murphy 902-883-7189 Advertising Manager: BMAC has an immediate requirement for a volunteer to help us to contact and present advertising op- portunities to potential clients. The job would entail approximately 5 hours per month and would consist of compiling a list of potential clients from among the bluegrass community, such as event-producers, bluegrass businesses, music stores, radio stations, bluegrass bands, music manufacturers and other interested parties. You would then set up a systematic and organized methodology for making contact and presenting the BMAC program. Please contact Mike Kirley or Gord Devries if you are interested in becoming part of the team. PRESIDENT’S MESSAGE Call us or visit our website Martha white brand is due to the www.bluegrassmusic.ca. -

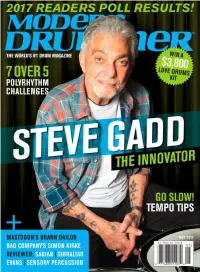

40 Steve Gadd Master: the Urgency of Now

DRIVE Machined Chain Drive + Machined Direct Drive Pedals The drive to engineer the optimal drive system. mfg Geometry, fulcrum and motion become one. Direct Drive or Chain Drive, always The Drummer’s Choice®. U.S.A. www.DWDRUMS.COM/hardware/dwmfg/ 12 ©2017Modern DRUM Drummer WORKSHOP, June INC. ALL2014 RIGHTS RESERVED. ROLAND HYBRID EXPERIENCE RT-30H TM-2 Single Trigger Trigger Module BT-1 Bar Trigger RT-30HR Dual Trigger RT-30K Learn more at: Kick Trigger www.RolandUS.com/Hybrid EXPERIENCE HYBRID DRUMMING AT THESE LOCATIONS BANANAS AT LARGE RUPP’S DRUMS WASHINGTON MUSIC CENTER SAM ASH CARLE PLACE CYMBAL FUSION 1504 4th St., San Rafael, CA 2045 S. Holly St., Denver, CO 11151 Veirs Mill Rd., Wheaton, MD 385 Old Country Rd., Carle Place, NY 5829 W. Sam Houston Pkwy. N. BENTLEY’S DRUM SHOP GUITAR CENTER HALLENDALE THE DRUM SHOP COLUMBUS PRO PERCUSSION #401, Houston, TX 4477 N. Blackstone Ave., Fresno, CA 1101 W. Hallandale Beach Blvd., 965 Forest Ave., Portland, ME 5052 N. High St., Columbus, OH MURPHY’S MUSIC GELB MUSIC Hallandale, FL ALTO MUSIC RHYTHM TRADERS 940 W. Airport Fwy., Irving, TX 722 El Camino Real, Redwood City, CA VIC’S DRUM SHOP 1676 Route 9, Wappingers Falls, NY 3904 N.E. Martin Luther King Jr. SALT CITY DRUMS GUITAR CENTER SAN DIEGO 345 N. Loomis St. Chicago, IL GUITAR CENTER UNION SQUARE Blvd., Portland, OR 5967 S. State St., Salt Lake City, UT 8825 Murray Dr., La Mesa, CA SWEETWATER 25 W. 14th St., Manhattan, NY DALE’S DRUM SHOP ADVANCE MUSIC CENTER SAM ASH HOLLYWOOD DRUM SHOP 5501 U.S. -

John Zorn Artax David Cross Gourds + More J Discorder

John zorn artax david cross gourds + more J DiSCORDER Arrax by Natalie Vermeer p. 13 David Cross by Chris Eng p. 14 Gourds by Val Cormier p.l 5 John Zorn by Nou Dadoun p. 16 Hip Hop Migration by Shawn Condon p. 19 Parallela Tuesdays by Steve DiPo p.20 Colin the Mole by Tobias V p.21 Music Sucks p& Over My Shoulder p.7 Riff Raff p.8 RadioFree Press p.9 Road Worn and Weary p.9 Bucking Fullshit p.10 Panarticon p.10 Under Review p^2 Real Live Action p24 Charts pJ27 On the Dial p.28 Kickaround p.29 Datebook p!30 Yeah, it's pink. Pink and blue.You got a problem with that? Andrea Nunes made it and she drew it all pretty, so if you have a problem with that then you just come on over and we'll show you some more of her artwork until you agree that it kicks ass, sucka. © "DiSCORDER" 2002 by the Student Radio Society of the Un versify of British Columbia. All rights reserved. Circulation 17,500. Subscriptions, payable in advance to Canadian residents are $15 for one year, to residents of the USA are $15 US; $24 CDN ilsewhere. Single copies are $2 (to cover postage, of course). Please make cheques or money ordei payable to DiSCORDER Magazine, DEADLINES: Copy deadline for the December issue is Noven ber 13th. Ad space is available until November 27th and can be booked by calling Steve at 604.822 3017 ext. 3. Our rates are available upon request. -

Mio Chris Thile Playlist

MIO CHRIS THILE PLAYLIST Cazadero Chris Thile CD: How to Grow a Woman From the Ground Improvisation Chris Thile Live -- New Orleans Carolina Drama Jack White A Prairie Home Companion Gone for Good The Shins A Prairie Home Companion Youtube Older and Taller Regina Spektor A Prairie Home Companion Youtube Kashmir Chris Thile and the Prairie Home Companion Band Youtube My Oh My Chris Thile Live -- New Orleans Monologue Chris Thile A Prairie Home Companion Eureka! Chris Thile CD: Not All Who Wander Are Lost Girl From Ipanema Joao & Astrud Gilberto and Stan Getz Single Don’t Try This At Home Bluegrass, Etc. CD: Bluegrass Etc. Tarnation Edgar Meyer & Chris Thile CD: Bass & Mandolin Quarter Chicken Dark Stuart Duncan, Chris Thile, Edgar Meyer, Yo-Yo Ma CD: The Goat Rodeo Sessions Kid A Punch Brothers CD: Who’s Feeling Young Now? Reckoner Chris Thile LIVE -- New Orleans Reckoner Radiohead CD: In Rainbows Rite of Spring Part I The Adoration of the Earth: I. Introduction Igor Stravinsky and the Columbia Symphony Orchestra CD: Igor Stravinsky Conducts Le Sacre Du Printemps (The Rite of Spring) For Free (Interlude) Kendrick Lamar CD: To Pimp A Butterfly Toxic Brittany Spears CD: In the Zone Gut Bucket Blues Don Vappie and the Creole Serenaders CD: Blues Routes: Heroes and Tricksters — Blues and Jazz Work Songs and Street Music I Made This For You Chris Thile Live -- New Orleans Joy Ride in a Toy Car/Hey Ho Mike Marshall & Chris Thile CD: Live Duets . -

2018–2019 Annual Report

18|19 Annual Report Contents 2 62 From the Chairman of the Board Ensemble Connect 4 66 From the Executive and Artistic Director Digital Initiatives 6 68 Board of Trustees Donors 8 96 2018–2019 Concert Season Treasurer’s Review 36 97 Carnegie Hall Citywide Consolidated Balance Sheet 38 98 Map of Carnegie Hall Programs Administrative Staff Photos: Harding by Fadi Kheir, (front cover) 40 101 Weill Music Institute Music Ambassadors Live from Here 56 Front cover photo: Béla Fleck, Edgar Meyer, by Stephanie Berger. Stephanie by Chris “Critter” Eldridge, and Chris Thile National Youth Ensembles in Live from Here March 9 Daniel Harding and the Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra February 14 From the Chairman of the Board Dear Friends, In the 12 months since the last publication of this annual report, we have mourned the passing, but equally importantly, celebrated the lives of six beloved trustees who served Carnegie Hall over the years with the utmost grace, dedication, and It is my great pleasure to share with you Carnegie Hall’s 2018–2019 Annual Report. distinction. Last spring, we lost Charles M. Rosenthal, Senior Managing Director at First Manhattan and a longtime advocate of These pages detail the historic work that has been made possible by your support, Carnegie Hall. Charles was elected to the board in 2012, sharing his considerable financial expertise and bringing a deep love and further emphasize the extraordinary progress made by this institution to of music and an unstinting commitment to helping the aspiring young musicians of Ensemble Connect realize their potential. extend the reach of our artistic, education, and social impact programs far beyond In August 2019, Kenneth J. -

Happy Traum……….…………………….….Page 2 Sun, July 11, at Fishing Creek Salem UMC • a Legend Ireland Tour…

Happy Traum……….…………………….….Page 2 Sun, July 11, at Fishing Creek Salem UMC • A legend Ireland Tour….......….......…..........….4 of American roots music joins us for a guitar workshop Folk Festival Scenes…………..…....8-9 and concert, with a blues jam in between. Emerging Artist Showcase………....6 Looking Ahead……………….…….…...12 Andy’s Wild Amphibian Show….........……..Page 3 Member Recognition.….................15 Wed, Jul 14 • Tadpoles, a five-gallon pickle jar and silly parental questions are just a few elements of Andy Offutt Irwin’s zany live-streamed program for all ages. Resource List Liars Contest……………....……….………...Page 3 Subscribe to eNews Wed, Jul 14 • Eight tellers of tall tales vie for this year’s Sponsor an Event Liars Contest title in a live-streamed competition emceed by storyteller extraordinaire Andy Offutt Irwin. “Bringing It Home”……….……...……........Page 5 Executive Director Jess Hayden Wed, Aug 11 • Three local practitioners of traditional folk 378 Old York Road art — Narda LeCadre, Julie Smith and Rachita Nambiar — New Cumberland, PA 17070 explore “Beautiful Gestures: Making Meaning by Hand” in [email protected] a virtual conversation with folklorist Amy Skillman. (717) 319-8409 Solo Jazz Dance Class……........................…Page 6 More information at Fri, Aug 13, Mt. Gretna Hall of Philosophy Building • www.sfmsfolk.org Let world-champion swing dancer Carla Crowen help get you in the mood to boogie to the music of Tuba Skinny. Tuba Skinny………………........................…Page 7 Fri, Aug 13, at Mt. Gretna Playhouse • This electrifying ensemble has captivated audiences around the world with its vibrant early jazz and traditional New Orleans sound. Nora Brown……………... Page 10 Sat, Aug 14, at Mt. -

Kelsea Ballerini Becomes Newest Member of Grand Ole Opry

Kelsea Ballerini Becomes Newest Member of Grand Ole Opry **MEDIA DOWNLOAD** Footage of Kelsea Ballerini’s Opry member induction available here: hps://vimeopro.com/user62979372/kelsea‑ballerini‑inducon Kelsea Ballerini inducted as a member of the Grand Ole Opry Kelsea Ballerini and Carrie Underwood performed Opry by Opry member Carrie Underwood member Trisha Yearwood’s 1992 hit “Walkaway Joe" Kelsea Ballerini becomes newest member of the Grand Ole Opry l to r: Grand Ole Opry's Sally Williams, Black River Entertainment's Kim and Terry Pegula,Kelsea Ballerini, Black River Entertainment's Gordon Kerr, Sandbox Entertainment's Jason Owen and Black River Entertainment's Rick Froio NASHVILLE, Tenn. (April 16, 2019) – Kelsea Ballerini was inducted as the newest and youngest current member of the Grand Ole Opry tonight by Carrie Underwood, an Opry member since 2008. Surprising the soldout Opry House crowd after Ballerini had performed a threesong set, Underwood took the stage and said to Ballerini, “You have accomplished so much in your career, and you will undoubtedly accomplish infinite amounts more in your life. Awards, number ones, sales ... this is better than all of that. This is the heart and soul of country music.” Presenting Ballerini with her Opry member award, Underwood cheered, “I am honored to introduce and induct the newest member of the Grand Ole Opry, Kelsea Ballerini.” After recounting her first visit to the Opry as a fan, her 2015 Opry debut, and subsequent Opry appearances, Ballerini held her award close and said, “Grand