The Vapour Revolution

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

University of Florida Thesis Or Dissertation

A SYSTEMATIC SCOPING REVIEW OF COMMUNICATION-BASED STUDIES ON CANCER PREVENTION AND DETECTION IN BANGLADESH By AANTAKI RAISA A THESIS PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN MASS COMMUNICATION UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2019 © 2019 Aantaki Raisa To my mom, sister and mentor, whose unconditional love, support and guidance have brought me where I am today, including the completion of this thesis ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to take this opportunity to thank Dr. Janice Krieger, my mentor, my advisor, who has taught me to be my best version, and inspired me to try relentlessly to excel. My gratitude is extended towards my thesis co-chair Dr. Carma Bylund, who has been my North Star, providing me directions in the very maze-like world of systematic reviews. I could not thank Dr. Frank Waddell enough, who took the time and effort to guide me through my thesis with his feedback, challenging insights and positivity. I would also like to take this opportunity to thank Mr. Reza Salim. I am forever in debt to him as he had introduced me to the world of translational science and to Dr. Krieger, where it all started for me. Finally, I would like to thank Taylor Thelander, a fellow master’s student, who came into my rescue to co-code within a short notice. I would also like to thank Dr. Alyssa Jaisle, who kept me accountable with my daily writing goals. Last but definitely not the least, I want to shout out to my STCC family, who has been a pillar of strength, support and love in my journey. -

Smoking Cessationreview Smoking Cessation YEARS Research Review MAKING EDUCATION EASY SINCE 2006

RESEARCH Smoking CessationREVIEW Smoking Cessation YEARS Research Review MAKING EDUCATION EASY SINCE 2006 Making Education Easy Issue 24 – 2016 In this issue: Welcome to issue 24 of Smoking Cessation Research Review. Encouraging findings suggest that varenicline may increase smoking abstinence rates in light smokers Have combustible cigarettes (5–10 cigarettes per day). However, since the study was conducted in a small cohort of predominantly White met their match? cigarette smokers, it will be interesting to see whether the results can be generalised to a larger population Supporting smokers with that is more representative of the real world. depression wanting to quit Computer-generated counselling letters that target smoking reduction effectively promote future cessation, Helping smokers quit after report European researchers. Their study enrolled smokers who did not intend to quit within the next diagnosis of a potentially 6 months. At the end of this 24-month investigation, 6-month prolonged abstinence was significantly higher curable cancer amongst smokers who received individually tailored letters compared with those who underwent follow-up assessments only. Preventing postpartum return to smoking We hope you enjoy the selection in this issue, and we welcome any comments or feedback. Varenicline assists smoking Kind Regards, cessation in light smokers Brent Caldwell Natalie Walker [email protected] [email protected] Novel pMDI doubles smoking quit rates Progress towards the Smokefree 2025 goal: too slow Independent commentary by Dr Brent Caldwell. Brent Caldwell was a Senior Research Fellow at Wellington Asthma Research Group, and worked on UK data show e-cigarettes are the Inhale Study. His main research interest is in identifying and testing improved smoking cessation linked to successful quitting methods, with a particular focus on clinical trials of new smoking cessation pharmacotherapies. -

Appendix 1: Codebook for “Content Analysis of E-Cigarette Products, Promotions, Prices and Claims on Internet Tobacco Vendor Websites, 2013-2014”

Appendix 1: Codebook for “Content Analysis of E-cigarette Products, Promotions, Prices and Claims on Internet Tobacco Vendor Websites, 2013-2014” (The following is a succinct version of the codebook intended to provide definitions for each variable; the original codebook used for training and reference by coders includes extensive text and graphic examples) Appendix Table 1. Codebook for Products sold by Internet Tobacco Vendors Selling E-Cigarettes Product (Variable) Codebook Definition Disposable e-cigarettes Any e-cigarette intended to be used and disposed of rather than refilled with e- liquids or cartridges. E-cigarette starter kit A kit containing everything needed to start vaping with a refillable e-cigarette, including the vaping device, battery, charger, and e-liquid or refill cartridges. Electronic cigars (e-cigars) An e-cigarette specifically made to resemble a large cigar, must use the term cigar, e.g. e-cigar or electronic cigar. Disposable e-cigars A disposable e-cigarette specifically made to resemble a large cigar (and be disposed of rather than refilled), must use the term cigar, e.g. e-cigar or electronic cigar. Most popular retail store Whether IEVs sold the five most popular e-cigarette brands in retail stores at the e-cigarette brands time of data collection (Blu, Njoy, Mistic, 21st Century Smoke, and Logic) were tracked in 2013. In 2014, Mistic and 21st Century Smoke were dropped because they were not found at all at IEVs in our 2013 sample, and four other brands found to be the most popular in our study of Google Search Trends were added to our brand tracking in 2014 (Joyetech, Ego, Nucig, and V2). -

Healthy Mouth, Healthy You the Connection Between Oral and Overall Health

Healthy Mouth, Healthy You The connection between oral and overall health Your dental health is part of a bigger picture: whole-body wellness. Learn more about the relationship between your teeth, gums and the rest of your body. We keep you smiling® deltadentalins.com/enrollees Pregnancy Pregnancy is a crucial time to take care of your oral health. Hormonal changes may increase the risk of gingivitis, or inflammation of the gums. Symptoms include tenderness, swelling and bleeding of the gums. Without proper care, these problems may become more serious and can lead to gum disease. Gum disease is linked to premature birth and low birth weight. If you notice any changes in your mouth during pregnancy, see your dentist. WHAT YOU CAN DO • Be vigilant about your oral health. Brush twice daily and floss at least once a day — these basic oral health practices will help reduce plaque buildup and keep your mouth healthy. • Talk to your dentist. Always let your dentist know that you are pregnant. • Eat well. Choose nutritious, well-balanced meals, including fresh fruits, raw vegetables and dairy products. Athletics Sports and exercise are great ways to build muscle and improve cardiovascular health, but they can also increase risks to your oral health. Intense exercise can dry out the mouth, leading to a greater chance of tooth decay. If you play a high-impact sport without proper protection, you risk knocking out a tooth or dislocating your jaw. WHAT YOU CAN DO • Hydrate early. Prevent dehydration by drinking water during your workout — and several hours beforehand. • Skip the sports drinks. -

July 2021 L.A. Care Health Plan Medi-Cal Dual Formulary

L.A. Care Health Plan Medi-Cal Dual Formulary Formulary is subject to change. All previous versions of the formulary are no longer in effect. You can view the most current drug list by going to our website at http://www.lacare.org/members/getting-care/pharmacy-services For more details on available health care services, visit our website: http://www.lacare.org/members/welcome-la-care/member-documents/medi-cal LA1308E 02/20 EN lacare.org Last Updated: 07/01/2021 INTRODUCTION Foreword Te L.A. Care Health Plan (L.A. Care) Medi-Cal Dual formulary is a preferred list of covered drugs, approved by the L.A. Care Health Plan Pharmacy Quality Oversight Committee. Tis formulary applies only to outpatient drugs and self-administered drugs not covered by your Medicare Prescription Drug Beneft. It does not apply to medications used in the inpatient setting or medical ofces. Te formulary is a continually reviewed and revised list of preferred drugs based on safety, clinical efcacy, and cost-efectiveness. Te formulary is updated on a monthly basis and is efective the frst of every month. Tese updates may include, and are not limited to, the following: (i) removal of drugs and/or dosage forms, (ii) changes in tier placement of a drug that results in an increase in cost sharing, and (iii) any changes of utilization management restrictions, including any additions of these restrictions. Updated documents are available online at: lacare.org/members/getting-care/pharmacy-services. If you have questions about your pharmacy coverage, call Customer Solutions Center at 1-888-839-9909 (TTY 711), available 24 hours a day, 7 days a week. -

Smoking Cessation by Changing the Way of Smoking: Case Report

Lopez et al., Prim Health Care 2018, 8:4 alt y He hca ar re : im O DOI: 10.4172/2167-1079.1000312 r p P e f n o A l c a c n e r s u s o Primary Health Care: Open Access J ISSN: 2167-1079 Case Report Open Access Smoking Cessation by Changing the Way of Smoking: Case Report Pedro J Tarraga Lopez1*, Loreto Tarraga-Marcos2, Ibrahim Sadek3, Fatima Madrona-Marcos3, Alicia Vivo3 and Carmen Celada4 1Department of Family Practice, Servicio de Salud de Castilla- La Mancha, Health Center number 5, Albacete, Albacete 02005, Spain 2Clinic Hospital Zaragoza, Servicio Aragones de Salud, Spain 3Department of Medicine, Servicio de Salud de Castilla-La Mancha, Albacete, Spain 4Department of Medicine, Servicio Murciano de Salud, Spain Abstract It is the case of a smoker woman over 45 years old who starts changing cigarettes to cigarettes without combustion with a significant improvement in the quality of life and at 9 months quit smoking completely. Keywords: Smoker; Change smoking; Cigarettes without of smoking has decreased in many developed countries, more than 1 combustion; Harm reduction by tobacco billion people continue to smoke in the world nowadays [1,2]. Case Report Many smokers want and try to quit, however, the long-term dropout rates are still very low. The public policies on tobacco control recommended Our patient is a 62 year-old woman, married with two children, by the World Health Organization are leading to an average annual decrease working as a community pharmacist. As for the medical history she between 0.5% and 1% in the prevalence of smoking in developed countries, had no known medical allergies, hypertensive in treatment, no Diabetes although the related mortality remains high. -

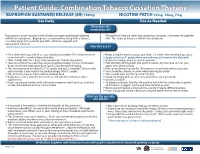

Bupropion + Patch

Patient Guide: Combination Tobacco Cessation Therapy BUPROPION SUSTAINED RELEASE (SR) 150mg NICOTINE PATCH 21mg, 14mg, 7mg Use Daily Use As Needed What does this medication do? Bupropion is a non-nicotine aid that helps you quit smoking by reducing The patch will release small, but continuous amounts of nicotine through the withdrawal symptoms. Bupropion is recommended along with a tobacco skin. This helps to decrease withdrawal symptoms. cessation program to provide you with additional support and educational materials. How do I use it? BUPROPION SUSTAINED RELEASE (SR) 150mg NICOTINE PATCH 21mg, 14mg, 7mg Set a date when you intend to stop smoking (quit date). The medicine needs Begin using the patch on your quit date, 1-2 weeks after starting bupropion. to be started 1-2 weeks before that date. Apply only one (1) patch when you wake up and remove the old patch. Take 1 tablet daily for 3 days, then increase to 1 tablet twice daily. If you miss a dose, use it as soon as you can. Take at a similar time each day, allowing approximately 8 hours in between Peel the back off the patch and put it on clean, dry, hair-free skin on your doses. Don’t take bupropion past 5pm to avoid trouble sleeping. upper arm, chest or back. This medicine may be taken for 7-12 weeks and up to 6 months. Discuss with Press patch firmly in place for 10 seconds so it will stick well to your skin. your provider if you need to be treated longer than 12 weeks. -

Use of Non Cigarette Tobacco Products (NCTP) Smokeless

Non Cigarette Tobacco Products (NCTP) and Electronic cigarettes (e-cigs) Michael V. Burke EdD Asst: Professor of Medicine Nicotine Dependence Center Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN Email: [email protected] ©2011 MFMER | slide-1 Goals & Objectives • Review NCTP definitions & products • Discuss prevalence/trends of NCTP • Discuss NCTP and addiction • Review recommended treatments for NCTP ©2011 MFMER | slide-2 NCTP Definitions & Products ©2011 MFMER | slide-3 Pipes ©2011 MFMER | slide-4 Cigars Images from www.trinketsandtrash.org ©2011 MFMER | slide-5 Cigar Definition U.S. Department of Treasury (1996): Cigar “Any roll of tobacco wrapped in leaf tobacco or any substance containing tobacco.” vs. Cigarette “Any roll of tobacco wrapped in paper or in any substance not containing tobacco.” ©2011 MFMER | slide-6 NCI Monograph 9. Cigars: Health Effects and Trends. ©2011 MFMER | slide-7 ©2011 MFMER | slide-8 Smokeless Tobacco Chewing tobacco • Loose leaf (i.e., Redman) • Plugs • Twists Snuff • Moist (i.e., Copenhagen, Skoal) • Dry (i.e., Honest, Honey bee, Navy, Square) ©2011 MFMER | slide-9 “Chewing Tobacco” = Cut tobacco leaves ©2011 MFMER | slide-10 “Snuff” = Moist ground tobacco ©2011 MFMER | slide-11 Type of ST Used in U.S. Chewing Tobacco Snuff National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH) ©2011 MFMER | slide-12 “Spitless Tobacco” – Star Scientific ©2011 MFMER | slide-13 RJ Reynold’s ©2011 MFMER | slide-14 “Swedish Style” ST ©2011 MFMER | slide-15 Phillip Morris (Altria) ©2011 MFMER | slide-16 New Product: “Fully Dissolvables” ©2011 MFMER -

Electronic Cigarettes

ELECTRONIC CIGARETTES WHAT ARE ELECTRONIC CIGARETTES? Electronic cigarettes, or e-cigarettes, are battery-operated devices that contain a mixture of liquid nicotine and other chemicals. The device heats this mixture, called e-juice, producing a nicotine aerosol that is inhaled. E-cigarettes are also called e-hookahs, e-pipes, vape pens, hookah pens or personal vaporizers. E-CIGARETTES ARE NOT PROVEN SAFE. There is currently no evidence that using e-cigarettes or inhaling the secondhand emissions from an e-cigarette is safe. Studies have found nicotine, heavy metals, toxins, and carcinogens in e-cigarette aerosol.1, 2, 3, 4 Blu is the market leader in e-cigarette sales. It is heavily marketed by celebrities. FDA NOW REGULATING E-CIGARETTES. The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) began a two-year process in 2016 to establish basic regulations for e-cigarettes. Before this, e-cigarettes were completely unregulated. These regulations: • Prohibit free samples of e-cigarette liquid made or derived from tobacco. • Require a thorough review process for any product marketed after Feb. 15, 2007. • Prohibit sales to minors. • Require manufacturers of e-cigarettes, liquid, or components and parts of electronic cigarettes to register with the FDA. • Prohibit the sale of e-cigarettes from vending machines, unless in an adult-only facility. • Prohibit sellers from claiming that their products are less hazardous than smoking unless they provide sufficient evidence to the agency. NJOY is a top seller and seeks to mimic • Require manufacturers to submit a list of ingredients for e-cigarette liquid. the feel of smoking. • Place warning labels on products. -

SA FUNDS INVESTMENT TRUST Form N-Q Filed 2016-11-23

SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION FORM N-Q Quarterly schedule of portfolio holdings of registered management investment company filed on Form N-Q Filing Date: 2016-11-23 | Period of Report: 2016-09-30 SEC Accession No. 0001206774-16-007593 (HTML Version on secdatabase.com) FILER SA FUNDS INVESTMENT TRUST Mailing Address Business Address 10 ALMADEN BLVD, 15TH 10 ALMADEN BLVD, 15TH CIK:1075065| IRS No.: 770216379 | State of Incorp.:DE | Fiscal Year End: 0630 FLOOR FLOOR Type: N-Q | Act: 40 | File No.: 811-09195 | Film No.: 162016544 SAN JOSE CA 95113 SAN JOSE CA 95113 (800) 366-7266 Copyright © 2016 www.secdatabase.com. All Rights Reserved. Please Consider the Environment Before Printing This Document UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D.C. 20549 FORM N-Q QUARTERLY SCHEDULE OF PORTFOLIO HOLDINGS OF REGISTERED MANAGEMENT INVESTMENT COMPANY Investment Company Act file number: 811-09195 SA FUNDS - INVESTMENT TRUST (Exact name of registrant as specified in charter) 10 Almaden Blvd., 15th Floor, San Jose, CA 95113 (Address of principal executive offices) (Zip Code) Deborah Djeu Chief Compliance Officer SA Funds - Investment Trust 10 Almaden Blvd., 15th Floor, San Jose, CA 95113 (Name and Address of Agent for Service) Copies to: Brian F. Link Mark D. Perlow, Esq. Vice President and Managing Counsel Counsel to the Trust State Street Bank and Trust Company Dechert LLP 100 Summer Street One Bush Street, Suite 1600 7th Floor, Mailstop SUM 0703 San Francisco, CA 94104-4446 Boston, MA 02111 Registrants telephone number, including area code: (800) 366-7266 Date of fiscal year end: June 30 Date of reporting period: September 30, 2016 Copyright © 2013 www.secdatabase.com. -

White Paper on E-Cigarettes

7 Cedar St., Suite A Summit, NJ 07901 Phone: 908-273-9368 Fax: 908-273-9222 Email: [email protected] www.njgasp.org Karen Blumenfeld, Director Tobacco Control Policy and Legal Resource Center [email protected] January 22, 2015 ELECTRONIC SMOKING DEVICES Introduction The electronic smoking device industry has evolved and now offers more products than electronic cigarettes, like hookah pens and electronic cigars. Some industry trade groups refer to these products as Personal Electronic Vaporizing Units (PEVUs). Throughout this paper, the term “e-cigarette” is used broadly to include all types of electronic smoking devices. Global Advisors on Smokefree Policy1 (“GASP”) has many health concerns regarding e-cigarette use and exposure, which are documented in this paper. The U.S. Food & Drug Administration (FDA), U.S. Senator Frank Lautenberg, the World Health Organization, and national advocacy organizations also voice their concerns about e-cigarettes. Local, county, state and international jurisdictions are restricting or banning the sale or use of e- cigarette products. I. Laws and Policies New Jersey restricts e-cigarette sales and use New Jersey was the first state in the nation to ban the use of e-cigarettes in public places and workplaces, effective March 13, 2010. On January 11, 2010, Governor Corzine signed into law A4227/A4228/S3053/S3054, banning e-cigarette use in public places and workplaces (amended 2006 NJ Smokefree Air Act), and banning e-cigarette sales to people 18 years and younger. The New Jersey Senate and Assembly both voted unanimously in favor of the law. See http://njgasp.org/sfaa_2010_w-ecigs.pdf and njleg.state.nj.us/2008/Bills/A4500/4227_U1.pdf. -

The Minefield of E-Cigarette Labeling and Promotion

The Minefield Of E-Cigarette Labeling And Promotion Law360, New York (October 2, 2015, based on alleged false advertising and other claims. 12:32 PM ET) -- The 2009 Family By way of example, in May 2015, a consumer Smoking Prevention and Tobacco advocacy group sued various e- cigarette distributors Control Act amended the Food, for allegedly failing to include Proposition 65 Drug, and Cosmetic Act and warnings on their labels advising consumers that use provides the U.S. Food and Drug Administration the of the products would cause exposure to nicotine, a authority to regulate the manufacture, distribution chemical allegedly known to cause reproductive and marketing of tobacco products. In April 2014, the toxicity.[2] FDA issued a proposed rule (the so-called deeming On Sept. 1, 2015, the makers of Blu e-cigarettes rule) that would deem electronic cigarettes to meet were sued in a proposed class action in federal court the statutory definition of “tobacco product,” thereby in California for alleged violations of California’s extending the FDA’s regulatory authority to e- Unfair Competition Law and Consumers Legal cigarettes.[1] Remedies Act for allegedly failing to disclose that When the deeming rule is finalized, e-cigarettes may their products expose users to formaldehyde.[3] In also become subject to many of the marketing May 2015, a federal judge in California also found restrictions that the FDA has already imposed on that portions of a purported class action complaint traditional tobacco products, such as banning against NJOY Inc. survived a motion to dismiss outdoor advertising within 1,000 feet of schools and because, in allegedly holding out propylene glycol — playgrounds and prohibiting brand sponsorships of a common ingredient in e-liquids — as “generally sports and entertainment events, among others.