The New College Institute: an Institutional Analysis of the Creation of an Organization of Higher Education in the Commonwealth of Virginia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Roanoke Bar Review June 2014

R OANOKE BAR REVIEW Roanoke Bar Review June 2014 INSIDE THIS ISSUE: RBA RECOGNIZES MUNDY FOR A L IFETIME OF ACHIEVEMENTS President’s Corner 2 B Y FRANK W. ROGERS, III, ESQ. Young Lawyer of the Year 2014: 2 Brandy M. Rapp, Esq. At its Law Day luncheon on May 1, 2014, the Roa- Views from the Bench: General 3 noke Bar Association presented G. Marshall Mundy with District Court Judge Jacqueline its highest honor, the Frank W. “Bo” Rogers, Jr. Lifetime F. Ward Talevi Achievement Award. This award recognizes an out- standing lawyer who embodies the highest standard of You and the Law: Aging with Dignity 3 personal and professional excellence in Southwest Vir- Reflections on the Virginia Women 5 ginia and, in doing so, enhances the image and esteem Attorneys Association of attorneys in the region. Roanoke Law Library News and 6 In his fifty-two years of practice, Marshall has dis- Information tinguished himself inside and outside of the courtroom. In recognition of his professional skills, Marshall is AV- Status of Federal Judgeship 6 rated by Martindale-Hubbell and listed by Best Lawyers Appointment in America, Virginia Super Lawyers, and Virginia’s Legal Whatever Happened to NAP Tax 7 Elite. He is a Fellow of the Virginia Law Foundation and Credits for Pro Bono Work? of the American College of Trial Lawyers, and he is an advocate in the American Board of Trial Advocates. RBA and BRLS Recognize Top 7 Contributors for Pro Bono Legal John Jessee of LeClairRyan has said, “From my very first jury trial with Marshall in Services for 2013 1980 until now, I have had the distinct pleasure of learning from one of the finest trial lawyers in Virginia. -

Collectively Voting One's Culture Laura L.L. Blevins Thesis Submitted

Collectively Voting One's Culture Laura L.L. Blevins Thesis submitted to the faculty of the Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts In Political Science Scott G. Nelson Timothy W. Luke Luke P. Plotica December 13, 2017 Blacksburg, VA Keywords: Southwest Virginia, political behavior, culture Copyright 2017 Laura L. L. Blevins Collectively Voting One’s Culture Laura L. L. Blevins ABSTRACT This thesis considers theoretically the institutional nature of culture and its strength as a determinant of political behavior in Southwest Virginia. Beginning with a description of the geography of Southwest Virginia and the demographics of the region’s inhabitants, the thesis proceeds to outline the cultural nuances of the region that make it ripe for misunderstanding by the outside world when attempting to explain the cognitive dissonance between voting behavior and regional needs. Then the thesis explores how the culture of the region serves as its own institution that protects itself from outside forces. This phenomenon is explained through an outline of the man-made institutions which have been forged to ensure long-term political power that itself protects the institution of regional culture. Further evidence is presented through voting and demographic data that solidifies the role of culture in determining political behavior. Collectively Voting One’s Culture Laura L. L. Blevins GENERAL AUDIENCE ABSTRACT This thesis considers the role culture plays in the voting behavior of Southwest Virginians. Beginning with a description of the geography of Southwest Virginia and the demographics of the region’s residents, the thesis proceeds to outline the cultural nuances of the region that make it ripe for misunderstanding by the outside world when attempting to explain the tendency of the region’s voters voting against their own best interests. -

Providing Compelling Public Service Media for Central and Southwest Virginia

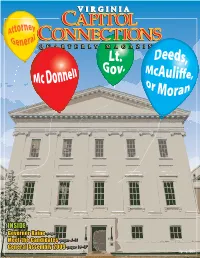

VV IRGINIAIRGINIA QUARTERLY MAGAZINE INSIDE Governor Kaine–page 2 Meet the Candidates–pages 4–11 General Assembly 2009–pages 16–17 Spring 2009 Jon Bowerbank Lieutenant Governor P. O. Box 800 Rosedale, VA 24280 (276) 596-9642 www.jonbowerbank.com Paid for and Authorized by Bowerbank for Lieutenant Governor V IRGINIAIRGINIA QUARTERLY MAGAZINEMAGAZINE SPRING 2009 ISSUE Costly Mistake . 2 Letter to the Editor . .2 2 Convention vs . Primary . 3 Governor Tim Kaine The Primary: The People’s choice . .3 Public Service is a Calling . 4 He Likes to Compete . 5 Bob McDonnell, Achiever . .6 4 Tried and True . .7 Bonnie Atwood VCCQM invites candidates to answer questions or submit short takes Bill Bolling (R) . 8 Jon Bowerbank (D) . .8 Patrick Muldoon (R) . 8 Mike Signer (D) . .9 Jody Wagner (D) . 9 John Brownlee (R) . 10. Ken Cuccinelli (R) . 10. Dave Foster (R) . 10. 6 Steve Shannon (D) . 11. Charlie Judd Charniele Herring . 12. Barry Knight . 13 Delores McQuinn . 13. Capitol Connections On The Scene . 14. GA 2009: Four Leaders Reflect onThe Good, The Bad and The Ugly 16 Delegate Sam Nixon . 16. Delegate Sam Nixon Delegate Ken Plum . 16. Senator Tommy Norment . 17. Senator Dick Saslaw . 17. When It Comes To Lobbying Madison Had It Right . 18. Another Missed Opportunity . 19. Virginia GOP Identity Crisis . 20. Feeding the Hungry . 21. 16 The Forgotten Party That Ruled Virginia . 21. Delegate Ken Plum Local Government Hires Ethicist . 22. “Little Things Mean A Lot”—At Keep Virginia Beautiful . 24. David Bailey Associates Announces New Associate . 25. In Memoriam— George Chancellor Rawlings, Jr . Charles Wesley “Bunny” Gunn, Jr . -

Southside Virginia: on the Map

V IRGINIA Q UARTERLY MAGAZINE Southside Virginia: On The Map INSIDE Virginia Civil Rights Memorial pages 7–11 A.L. Philpott page 16 Virginia International Raceway Southside Virginia—pages 12–25 page 14 Summer–Fall 2008 Jon Bowerbank Lieutenant Governor P. O. Box 800 Rosedale, VA 24280 (276) 596-9642 www.jonbowerbank.com Paid for and Authorized by Bowerbank for Lieutenant Governor V IRGINIAIRGINIA QUARTERLY MAGAZINEMAGAZINE 2 3 SUMMER –FALL 2008 ISSUE Bill Shendow Stephen J. Farnsworth Virginia’s Appalachian Vote and the Commonwealth’s Presidential Race .................2 Whither Virginia U.S. Senate Campaign?....................3 Civil Rights Presidential Characteristics Voters Like ....................4 Cracking Down on Counterfeiters .........................6 Memorial Regulatory and Infrastructure Reforms .....................6 Dedication VIRGINIA CIVIL RIGHTS ME M ORIAL DE D I C ATION The New Capitol Square ...............................7 Photo by Michaele L. White 7 Virginia Civil Rights Memorial Dedication ..................8 Around Capitol Square ................................8 Virginia Civil Rights Memorial Dedication Celebration ........10 Stardate Number 18628.190...........................11 SOUTHSI D E VIRGINIA The Future of Economic Development In Southern Virginia .....12 12 13 14 The Economic Resurgence of Southern Virginia .............13 Patrick O. Gottschalk Frank Ruff Charles Todd Southside Virginia’s Motorsports’ Resort..................14 In Remembrance of A.L. Philpott .......................16 A State Legislator’s -

Tobacco Industry Political Influence and Tobacco Control Policy in Virginia, 1977-2009

UCSF Tobacco Control Policy Making: United States Title The High Cost of Compromise: Tobacco Industry Political Influence and Tobacco Control Policy in Virginia, 1977-2009 Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/3gm9794g Authors Kierstein, Alex, JD Barnes, Richard L., JD Glantz, Stanton A., PhD Publication Date 2010-04-01 eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California The High Cost of Compromise: Tobacco Industry Political Influence and Tobacco Control Policy in Virginia, 1977-2009 Alex Kierstein, JD Richard L. Barnes, JD Stanton A. Glantz, PhD Center for Tobacco Control Research and Education School of Medicine University of California, San Francisco San Francisco, CA 94143-1390 April 2010 The High Cost of Compromise: Tobacco Industry Political Influence and Tobacco Control Policy in Virginia, 1977-2009 Alex Kierstein, JD Richard L. Barnes, JD Stanton A. Glantz, PhD Center for Tobacco Control Research and Education School of Medicine University of California, San Francisco San Francisco, CA 94143-1390 April 2010 Supported in part by National Cancer Institute Grant CA-61021 and endowment funds available to Dr. Glantz. Opinions expressed reflect the views of the authors and do not necessarily represent the sponsoring agency. This report is available at http://escholarship.org/uc/ctcre_tcpmus. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY • Tobacco use is the leading preventable cause of death in Virginia, taking more than 9,200 lives each year. Tobacco-induced healthcare costs are $1.92 billion annually, including $369 million in Medicaid payments. • The growth of tobacco, and its importance to the economy of Virginia, has declined significantly. In 2008, tobacco was only the fifth most harvested and valuable crop, behind hay, corn, soybeans, and wheat, and constituted only 2.3% of the value of all Virginia agricultural products sold. -

Architectural Survey of Henry County--Martinsville, Virginia

ARCHITECTURAL SURVEY OF HENRY COUNTY--MARTINSVILLE, VIRGINIA Prepared by: Hill Studio, P.C. 120 West Campbell Avenue Roanoke, VA 24011 540-342-5263 August 6, 2009 Prepared For: The Henry County- Martinsville Preservation Virginia Department National Trust for Historic Alliance with the Rural of Historic Resources Preservation Heritage Development 2801 Kensington Avenue 1785 Massachusetts Ave., NW Initiative Richmond, VA 23221 Washington DC 20036 Architectural Survey of Henry County Table of Contents Hill Studio, P.C. Page i TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Figures and Tables..............................................................................................................iii Abstract........................................................................................................................................... 5 Acknowledgements......................................................................................................................... 5 Project Background......................................................................................................................... 6 Introduction............................................................................................................................... 6 Project Description.................................................................................................................... 6 Methodology................................................................................................................................... 8 Previous Architectural -

Architectural Survey of Henry County Table of Contents Hill Studio, P.C

Architectural Survey of Henry County Table of Contents Hill Studio, P.C. Page i TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Figures and Tables..............................................................................................................iii Abstract........................................................................................................................................... 5 Acknowledgements......................................................................................................................... 5 Project Background......................................................................................................................... 6 Introduction............................................................................................................................... 6 Project Description.................................................................................................................... 6 Methodology................................................................................................................................... 8 Previous Architectural Investigations....................................................................................... 8 Research Methodology Prior to Field Study............................................................................. 9 On-Site Survey Methodology ................................................................................................... 9 Historic Contexts .........................................................................................................................