WATER RESOURCES/LITIGATION Special Report #2282 Montana V

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bill Mckinney Puts It Much More Simply: ''Ra:Nchpeople Have Always Been a Sort of Independent Breed

UneR~T U 4-High Country News Friday, Aug. 30, 1974 Sara Gaskin: "They'd have to shoot me first be- , Conflict ••• ,fore they came in here. Money (Continued from page 1) 'won't do it. I'd rather leave my land with draglines and shovels she hopes she'll outfit to charity." have "enough courage to hold them off with a gun in each hand." Cotton says she never stopped to think about asking how much the coal man was offering for "Dad came into this country on a cattle drive her land because she was too mad. before the Custer battle. He returned here to homestead soon after the fight," says Sara T. When she was told that her neighbor' Taylor Gaskin, a rancher along Otter Creek. : Cox had turned down an offer of $13 million for , "Dad liked this country because of all the coal his surface she remarked, "No wonder! Thirteen and wood in the area. He'd turn over in his million? That's pime! This land is more precious grave if he knew what was happening here and valuable than any coal they'll ever dig out now." , of it." The original homestead was deeded to Gas- , I~ July Cotton and some of her neighbors , .kill, Other parts of her ranch were bought from erected a rawhide sign on the Kirby-Birney di- the Burlington Northern Railroad. The miner- vide on her property to protest "seeing their als still belong to BN.-· . places turned into a National Sacrifice Area." , "You can understand why I don't want to give The divide is.one of the areas that the Decker- up my land. -

History of Navigation on the Yellowstone River

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers Graduate School 1950 History of navigation on the Yellowstone River John Gordon MacDonald The University of Montana Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation MacDonald, John Gordon, "History of navigation on the Yellowstone River" (1950). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 2565. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/2565 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. HISTORY of NAVIGATION ON THE YELLOWoTGriE RIVER by John G, ^acUonald______ Ë.À., Jamestown College, 1937 Presented in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Mas ter of Arts. Montana State University 1950 Approved: Q cxajJL 0. Chaiinmaban of Board of Examiners auaue ocnool UMI Number: EP36086 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. UMT Ois8<irtatk>n PuUishing UMI EP36086 Published by ProQuest LLC (2012). Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. -

Geologic Map of the Red Lodge Area, Carbon

GEOLOGIC MAP OF THE RED LODGE AREA, CARBON COUNTY, MONTANA by David A. Lopez Montana Bureau of Mines and Geology Open-File Report MBMG 524 2005 This map has been reviewed for conformity with technical and editorial standards of the Montana Bureau of Mines and Geology. Partial support has been provided by the STATEMAP component of the National Cooperative Geologic Mapping Program of the U.S. Geological Survey under Contract Number 04HQAG0079. Kalispell MONTANA 15 Great Falls 90 Missoula Helena 94 Butte Billings Bozeman 90 90 15 110° 109° Big Timber YELLOWSTONE CO 94 Y Billings r 90 e r e l SWEET GRASS CO v l owsto e i n v R e Riv i r e 90 R e r ld u ne o to B ws STILLWATER CO lo Columbus el Y 45°30' e 78 n o r t ive 212 s R w r o te l a l w e ll Y ti S e h CARBON CO t BIG HORN CO f o Luther k STUDY r o Red Lodge 72 F AREA s rk la C 310 N PARK CO 212 45° 10 0 10 20 Miles Figure 1. Location map of the study area. 1 2 DESCRIPTION OF MAP UNITS SURFICIAL DEPOSITS af Artificial fill—Mine tailings and fill in the Rock Creek valley in northern part of the town of Red Lodge. Qal Alluvium (Holocene)—Gravel, sand, silt, and clay along active stream channels. Qc Colluvium (Holocene and Pleistocene)—Locally derived slope-wash depositsmainly of sand, silt, and clay. Typically thin veneer concealing bedrock, but locally as thick as 30 ft (9 m). -

Montana State Parks Guide Reservations for Camping and Other Accommodations: Toll Free: 1-855-922-6768 Stateparks.Mt.Gov

For more information about Montana State Parks: 406-444-3750 TDD: 406-444-1200 website: stateparks.mt.gov P.O. Box 200701 • Helena, MT 59620-0701 Montana State Parks Guide Reservations for camping and other accommodations: Toll Free: 1-855-922-6768 stateparks.mt.gov For general travel information: 1-800-VISIT-MT (1-800-847-4868) www.visitmt.com Join us on Twitter, Facebook & Instagram If you need emergency assistance, call 911. To report vandalism or other park violations, call 1-800-TIP-MONT (1-800-847-6668). Your call can be anonymous. You may be eligible for a reward. Montana Fish, Wildlife & Parks strives to ensure its programs, sites and facilities are accessible to all people, including those with disabilities. To learn more, or to request accommodations, call 406-444-3750. Cover photo by Jason Savage Photography Lewis and Clark portrait reproductions courtesy of Independence National Historic Park Library, Philadelphia, PA. This document was produced by Montana Fish Wildlife & Parks and was printed at state expense. Information on the cost of this publication can be obtained by contacting Montana State Parks. Printed on Recycled Paper © 2018 Montana State Parks MSP Brochure Cover 15.indd 1 7/13/2018 9:40:43 AM 1 Whitefish Lake 6 15 24 33 First Peoples Buffalo Jump* 42 Tongue River Reservoir Logan BeTableaverta ilof Hill Contents Lewis & Clark Caverns Les Mason* 7 16 25 34 43 Thompson Falls Fort3-9 Owen*Historical Sites 28. VisitorMadison Centers, Buff Camping,alo Ju mp* Giant Springs* Medicine Rocks Whitefish Lake 8 Fish Creek 17 Granite11-15 *Nature Parks 26DisabledMissouri Access Headw ibility aters 35 Ackley Lake 44 Pirogue Island* WATERTON-GLACIER INTERNATIONAL 2 Lone Pine* PEACE PARK9 Council Grove* 18 Lost Creek 27 Elkhorn* 36 Greycliff Prairie Dog Town* 45 Makoshika Y a WHITEFISH < 16-23 Water-based Recreation 29. -

OUT HERE, WE HAVE a STORY to TELL. This Map Will Lead You on a Historic Journey Following the Movements of Lt

OUT HERE, WE HAVE A STORY TO TELL. This map will lead you on a historic journey following the movements of Lt. Col. Custer and the 7th Calvary during the days, weeks and months leading up to, and immediately following, the renowned Battle of Little Bighorn were filled with skirmishes, political maneuvering and emotional intensity – for both sides. Despite their resounding victory, the Plains Indians’ way of life was drastically, immediately and forever changed. Glendive Stories of great heroism and reticent defeat continue to reverberate through MAKOSHIKA STATE PARK 253 the generations. Yet the mystique remains today. We invite you to follow the Wibaux Trail to The Little Bighorn, to stand where the warriors and the soldiers stood, 94 to feel the prairie sun on your face and to hear their stories in the wind. 34 Miles to Theodore Terry Roosevelt Fallon National Park 87 12 Melstone Ingomar 94 PIROGUE Ismay ISLAND 12 12 Plevna Harlowton 1 Miles City Baker Roundup 12 89 12 59 191 Hysham 12 4 10 2 12 14 13 11 9 3 94 Rosebud Lavina Forsyth 15 332 447 16 R MEDICINE E ER 39 IV ROCKS IV R R 5 E NE U STATE PARK Broadview 87 STO 17 G OW Custer ON L T NORTH DAKOTA YE L 94 6 59 Ekalaka CUSTER GALLATIN NF 18 7 332 R E 191 IV LAKE Colstrip R MONTANA 19 Huntley R 89 Big Timber ELMO E D Billings W 447 O 90 384 8 P CUSTER Reed Point GALLATIN Bozeman Laurel PICTOGRAPH Little Bighorn Battlefield NATIONAL 90 CAVES Hardin 20 447 FOREST Columbus National Monument Ashland Crow 212 Olive Livingston 90 Lame Deer WA Agency RRIO SOUTH DAKOTA R TRA 212 IL 313 Busby -

Trails and Aboriginal Land Use in the Northern Bighorn Mountains, Wyoming

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers Graduate School 1992 Trails and Aboriginal land use in the northern Bighorn Mountains, Wyoming Steve Platt The University of Montana Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Platt, Steve, "Trails and Aboriginal land use in the northern Bighorn Mountains, Wyoming" (1992). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 3933. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/3933 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Maureen and Mike MANSFIELD LIBRARY Copying allowed as provided under provisions of the Fair Use Section of the U.S. COPYRIGHT LAW, 1976. Any copying for commercial purposes or financial giain may be undertaken only with the author's written consent. MontanaUniversity of TRAILS AND ABORIGINAL LAND USE IN THE NORTHERN BIGHORN MOUNTAINS, WYOMING By Steve Piatt B.A. University of Vermont, 1987 Presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts University of Montana 19-92 Approved by 4— Chair, Board of Examiners Death, Graduate £>c3Tooi 7 is. rtqz Date UMI Number: EP36285 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. -

Supreme Court of the United States

No. 137, Original IN THE Supreme Court of the United States ———— October Term 2014 ———— STATE OF MONTANA, Plaintiff, v. STATE OF WYOMING and STATE OF NORTH DAKOTA, Defendants. ———— SECOND INTERIM REPORT OF THE SPECIAL MASTER (LIABILITY ISSUES) ———— BARTON H. THOMPSON, JR. Special Master Stanford, California December 29, 2014 WILSON-EPES PRINTING CO., INC. – (202) 789-0096 – WASHINGTON, D. C. 20002 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page TABLE OF AUTHORITIES ................................ viii LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS ............................... xxi I. INTRODUCTION ..................................... 1 II. THE RECORD .......................................... 3 III. FACTUAL BACKGROUND ..................... 4 A. The Tongue River ................................ 4 B. Tongue River Water Use ..................... 8 1. Wyoming’s use of the Tongue River ............................................... 9 2. Montana’s use of the Tongue River ........................................................ 10 C. The Tongue River Reservoir ............... 12 IV. LEGAL BACKGROUND .......................... 14 A. The Yellowstone River Compact ......... 14 1. Key provisions of the Compact ...... 14 2. Difficulties in administering the Compact .......................................... 18 B. Western Water Law ............................ 18 C. The Northern Cheyenne Compact ...... 22 V. PROCEDURAL HISTORY ....................... 24 A. Montana v. Wyoming, 131 S. Ct. 1765 (2011) ................................................... 25 B. Subsequent Pre-Trial Proceedings .... -

Big Horn County Growth Policy May 2014

2014 Big Horn County Growth Policy May 1, 2014 Prepared by Cossitt Consulting PO Box 1493, Helena, MT [email protected] RESOLUTION OF ADOPTION……………………………..………………………………….vi 1. PURPOSE AND SCOPE ..................................................................................................... 1 1.1 Purpose .................................................................................................................................. 1 1.2 Geographic Scope ................................................................................................................. 1 1.3 Authority ............................................................................................................................... 1 1.4 Comprehensive Planning in Big Horn County ..................................................................... 1 1.5 Planning Process ................................................................................................................... 4 1.6 How This Plan is Organized ................................................................................................. 4 2. HISTORICAL BACKGROUND AND SETTING ............................................................... 7 3. TRENDS AND ISSUES ...................................................................................................... 10 3.1 Developments and Trends 2002-2012 ................................................................................ 10 3.2 Recent Trends/Issues ......................................................................................................... -

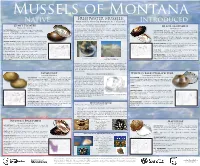

Native Introduced

Mussels of Montana Freshwater Mussels: Native Montana’s Hidden Biological Treasure Introduced Mussels are a seldom seen and under-appreciated biological component of Giant Floater many Montana trout streams and prairie rivers. Black Sandshell Pyganodon grandis Montana’s only trout stream mussel, the Western Pearlshell has been Ligumia recta DESCRIPTION: Shell is up to 6 inches long. Generally thin, disappearing from watersheds for decades. Before mining and dams, the DESCRIPTION: Elongate, pointed shell normally 5-6 inches long elliptical & light weight. Hinge has no teeth. Shell color is Clark Fork River had abundant populations. with a convex ventral edge. Shell interior (nacre) has a purple brownish to tan-green, inside pearly-blue sheen. to pink hue. Outside of shell can be dark brown to black. Few people know Montana has native freshwater mussels; even fish biologists STATUS: Native-G5 S4, globally common, statewide common and fishing guides who spend thousands of hours on rivers may not realize STATUS: Introduced-G5 SNA, globally common, statewide and secure populations. that they are floating over or “stepping on” these cryptic organisms (most resemble rocks on the river bottom). common, Regionally Rare (a species of concern S2 & S3 in many Midwestern states). PRIMARY HABITAT: Prefer pool and side channel areas of small to large warm prairie rivers with a mud, sand or gravel substrate. PRIMARY HABITAT: Medium to large warm prairie rivers in riffles This mussel is tolerant of silt and warm water temperatures. or runs with pebble, gravel or firm sand substrates. This mussel is fairly intolerant of silt and warm water temps. -

Actions with Indians, 1873

Actions with Indians 1873 2 January 1873 - Clear Creek Canyon, Arizona (Lt W F Rice) Detachment K Troop 5th Cavalry Company G 23rd Infantry Indian Scout 1 wounded 12 January 1873 - Tule Lake, California (Captain R F Bernard) G Troop 1st Cavalry 1 wounded 16 January 1873 - Superstition Mountain, Arizona (Captain W H Brown) B, C, G, H, L & M Troops 5th Cavalry 4 Indians killed, 12 Indians captured 17 January 1873 - Modoc Caves in Lava Beds near Tule Lake, California (Lt Col F Wheaton) B, F & G Troops 1st Cavalry Companies B & C 21st Infantry Detachment Company F 21st Infantry California Volunteers Oregon Volunteers 9 killed, 30 wounded 19 January 1873 - East Fork of Verde River, Arizona (Sergeant W L Day) Detachment of Scouts 5 Indians killed 20 January 1873 - Lower Miembres, New Mexico (Lt J D Stevenson) I Troop 8th Cavalry 1 Indian killed 22 January 1873 - Tonto Creek, Arizona (Lt F Michier) K Troop 5th Cavalry 1 wounded 17 Indians killed 6 February 1873 - Hell Canyon, Arizona (Captain T McGregor) Detachment A Troop 1st Cavalry 2 Indians killed, 1 Indian captured 20 February 1873 - Fossil Creek, Arizona (Captain C C C Carr) I Troop 1st Cavalry 5 Indians killed, 4 Indians captured 26 February 1873 - Angostura, New Mexico (Sergeant J F Rowalt) L Troop 8th Cavalry 5 Indians killed, 7 Indians wounded 19 March 1873 - Mazatzal Mountains, Arizona (Lt F Michier) K Troop 5th Cavalry 8 Indians killed, 5 Indians captured 1 25 March 1873 - Turret Mountains, Arizona (Sergeant S M Hill) Detachment A Troop 5th Cavalry 10 Indians killed, 3 Indians captured -

EST. 1898 ±3,800 Deeded Acres & 880 BLM Lease Dayton, Wyoming

The Hoffman Company years leading the land 3 brokerage industry 5 CALIFORNIA + NEVADA EST. 1898 ±3,800 Deeded Acres & 880 BLM Lease Dayton, Wyoming Sheridan County - Big Horn Mountains Working Cattle & Horse Ranch | Hunting | Fishing | Recreation | Environmental Retreat Dye Designed Golf Course | Recorded Country Club of the Big Horns Golf Community Location Introduction The Horseshoe Ranch is located on the eastern slope of the Bighorn Mountains in northern Wyoming, 18 miles west of Sheridan. The Horseshoe enjoys complete solitude and privacy. It is bounded by other legacy ranches to the northeast and southeast, including the historic Eatons’ Dude Ranch, es- Situated at the foot of the spectacular Big Horn Mountains, Horseshoe Ranch is located in tablished in 1904. In the southwest, the ranch is bounded by the Bighorn Mountains and associated National Forest. The ranch’s only improvements (the main house, guest homes, barns, shop, golf Sheridan County just west of the City of Dayton, Wyoming. The ±4,680 acre ranch is secured course, clubhouse and hay meadows) are all nestled out of sight in the Little Tongue River Valley. While the Horseshoe does enjoy complete solitude and privacy, it is also conveniently located 1.5 with entitlements to build an exclusive golf course community. The ranch adjoins the famous miles off of Highway 14; which borders the ranch to the northwest. Exiting the ranch and turning Eatons’ Dude Ranch and federal lands administered by the Bureau of Land Management and right on Highway 14 leads to Dayton, WY. Dayton is a 5-10 minute drive from the main gate of the Horseshoe and has amenities that include a grocery store, a post office, a café, 2 bars, a community is immediately accessible to miles of hiking, hunting, fishing, and horseback riding that the center, a brand new high school, a public swimming pool and a park. -

American Journal of Science, Vol

[American Journal of Science, Vol. 311, December, 2011,P.813–850, DOI 10.2475/10.2011.01] American Journal of Science DECEMBER 2011 MAGNETOSTRATIGRAPHY OF THE LEBO AND TONGUE RIVER MEMBERS OF THE FORT UNION FORMATION (PALEOCENE) IN THE NORTHEASTERN POWDER RIVER BASIN, MONTANA DANIEL J. PEPPE*, KIRK R. JOHNSON**, and DAVID A. D. EVANS*** ABSTRACT. We analyzed paleomagnetic samples and documented the stratigraphy from two sections near Miles City, Montana to determine the geomagnetic polarity stratigraphy and to constrain the age and duration of the Lebo and Tongue River Members of the Fort Union Formation in the northeastern Powder River Basin. The resulting polarity sequence can be correlated to subchrons C29n–C26r of the geomag- netic polarity time scale. By interpolating measured sediment accumulation rates from the base of C28r to the top of C27n, and then extrapolating to the top of the Tongue River Member and the bottom of the Lebo Member, we developed two age models to estimate the durations of the Lebo and Tongue River Members. Based on the first model, which uses different sedimentation rates for the Lebo and Tongue River Members, we estimate the duration of deposition of the Lebo to be between 1.30 and 1.74 million years and of the Tongue River to be between 1.42 and 1.61 million years. Using the second model, which uses the same sedimentation rate for the Lebo and Tongue River Members, we estimate the duration of deposition of the Lebo to be between 1.33 and 1.76 million years and of the Tongue River to be between 1.00 and 1.25 million years.