In Their Shoes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Support Hosiery Support Hosiery

Support Hosiery Support Hosiery 3M Consumer Products 3M Consumer Products Futuro™ Energizing Trouser Futuro™ Restoring Socks for Women Dress Socks for Men • Use for tired achy legs, mild spider and varicose • Use for more pronounced varicose veins, veins, mild swelling edema, ulcerations, moderate ankle swelling, • Graduated compression improves circulation moderate/severe leg pain, chronic leg fatigue with maximum compression at the ankle that and heaviness gradually decreases up the leg to provide an • Over calf style energizing feeling • Graduated compression improves circulation with maximum compression at the ankle that CIN Mfr. No. Description Color Size Qty. gradually decreases up the leg to provide an energizing feeling 3266822 70123 8-15mmHg Black Large 1 Pr CIN Mfr. No. Description Color Size Qty. 1345933 71035B 15-20mmHg Brown Medium 1/pr 1345974 71035B 20-30mmHg Black Medium 1/pr 1345982 71036B 20-30mmHg Black Large 1/pr 3M Consumer Products 1345941 71036B 20-30mmHg Brown Large 1/pr Futuro™ Energizing 1010727 71037E 20-30mmHg Black X-large 1/pr UltraSheer Knee Highs • For tired or achy legs, mild spider and varicose veins and mild swelling • Comfort band won’t bind and keeps knee highs from rolling down 3M Consumer Products • Silky-soft material has a reinforced toe and heel Futuro™ Restoring Pantyhose Brief Cut Panty CIN Mfr. No. Description Color Size Qty. • Use for more pronounced varicose veins, 1174549 71013N 8-15mmHg Nude Small 1/pr edema, ulcerations, moderate ankle 1174606 71014N 8-15mmHg Nude Medium 1/pr swelling, moderate/severe leg pain, 1174630 71015N 8-15mmHg Nude Large 1/pr chronic leg fatigue and heaviness CIN Mfr. -

A Story About Running

Bard College Bard Digital Commons Senior Projects Spring 2018 Bard Undergraduate Senior Projects Spring 2018 Contact! A Story about Running Sara Bosworth Bard College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.bard.edu/senproj_s2018 Part of the Nonfiction Commons This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. Recommended Citation Bosworth, Sara, "Contact! A Story about Running" (2018). Senior Projects Spring 2018. 305. https://digitalcommons.bard.edu/senproj_s2018/305 This Open Access work is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been provided to you by Bard College's Stevenson Library with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this work in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights- holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/or on the work itself. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Contact! A Story about Running By Sara Bosworth Contact! A story about running Senior Project submitted to The Division of Languages and Literature of Bard College By Sara Bosworth Annandale-on-Hudson, New York May 2018 For Neno Acknowledgements SUSAN ROGERS, my beloved editor who always encouraged me to push more, go a bit further. Without you, this project never would have found its shape. Who knows, if I had you at the sidelines, maybe I could run a fifty-mile race after all. WYATT MASON, a dear mentor who has made me a better writer and a clearer thinker. -

A Roman Frontier Post and Its People

CHAPTER IX Dress and Armour As we gather together the relics brought to light from the abandoned wells and rubbish-pits at Newstead, the figure of the Roman soldier inevitably rises before us. It is a figure rendered familiar by the great monuments which commemorate Imperial triumphs, and by the portrait-reliefs which once stood above the graves of centurions, cavalry soldiers, or standard-bearers recalling to the passers-by the likeness of the dead. It is to such memorials, and to the scanty finds of weapons and armour which have been preserved to our time, that we owe most of the knowledge we possess regarding the arms and equipment of the army of the Empire. The columns and the triumphal arches furnish us with a series of pictures of the soldier in action. The victories of Trajan over the Dacians are sculptured on the column which he had set up in Rome in A.D. 104. The triumphs of Marcus Aurelius over the Marcomanni are unfolded in the reliefs decorating the huge pillar that gives its name to the Piazza Colonna. We follow each stage in the campaigns, the army making roads, building bridges, constructing forts, attacking and attacked. Many details are given which help us to realise vividly the scenes commemorated. No doubt in such sculptures, executed, as they were, in Rome, the artists drew their inspiration to some extent from older Hellenic models, and there thus enters into the treatment a somewhat conventional element. The grave stones of the legionaries or auxiliaries, on the other hand, are probably more exact in details. -

”Shoes”: a Componential Analysis of Meaning

Vol. 15 No.1 – April 2015 A Look at the World through a Word ”Shoes”: A Componential Analysis of Meaning Miftahush Shalihah [email protected]. English Language Studies, Sanata Dharma University Abstract Meanings are related to language functions. To comprehend how the meanings of a word are various, conducting componential analysis is necessary to do. A word can share similar features to their synonymous words. To reach the previous goal, componential analysis enables us to find out how words are used in their contexts and what features those words are made up. “Shoes” is a word which has many synonyms as this kind of outfit has developed in terms of its shape, which is obviously seen. From the observation done in this research, there are 26 kinds of shoes with 36 distinctive features. The types of shoes found are boots, brogues, cleats, clogs, espadrilles, flip-flops, galoshes, heels, kamiks, loafers, Mary Janes, moccasins, mules, oxfords, pumps, rollerblades, sandals, skates, slides, sling-backs, slippers, sneakers, swim fins, valenki, waders and wedge. The distinctive features of the word “shoes” are based on the heels, heels shape, gender, the types of the toes, the occasions to wear the footwear, the place to wear the footwear, the material, the accessories of the footwear, the model of the back of the shoes and the cut of the shoes. Keywords: shoes, meanings, features Introduction analyzed and described through its semantics components which help to define differential There are many different ways to deal lexical relations, grammatical and syntactic with the problem of meaning. It is because processes. -

Russell Moccasin Sale List Revised 06/01

Revised 9-23-21 GUSTIN BIRDSHOOTER GUSTIN R-12D-40, L-12 ½ D-40, ball to EE, lt High instep 400.00 GUSTIN R-12D-77, L-12 ½ D-77, ball to 3E, olympic sole 400.00 Russell Moccasin “SPECIAL” Sale List consists of samples, over runs, returned items, etc. All items are new & not seconds except as noted. Price pertains only to special UPLANDER terms & sizes listed below. When ordering men’s sizes from the list keep in mind that men’s double moccasin bottom UPLANDER 9 ½ E, ball to 5E, extra High instep, longer 2nd toe 417.00 and triple vamp style boots and shoes run ½ size longer UPLANDER 10-40, 3E, ball to 5E, High instep, pss 390.00 than single or double vamp styles. When ordering ladies sizes they run 1-1 ½ sizes longer than normal women’s PRICKLY PEAR BIRD SHOOTER boots or shoes. Some examples are as follows 8D=7D, 9A=8C, 7 AAA=6A 7 ½ AA=6 ½ B. Women’s triple vamp PPNS3090-27V 11B-40, ball to D, lt. High instep 12” 545.00 boots or shoes run 1 ½ sizes longer. Examples8A=6 ½, ½ B=5D. Please call if in doubt. If you would like you can send in tracings & measurements, & we can recommend a WYMAN BOOT size. Items listed as 9 ½ C Ball to D mean the heel is narrower than the ball. We are not responsible for shipping Wyman 9C, ball to D 410.00 Wyman 9 ½ B-40, ball to D 430.00 on returned sale items. If an item is worn or of a different leather, we can e-mail you a picture, otherwise they are the same as on our website & you can view them there. -

“All Shoe Fashions from 7 Basic Styles” by William Rossi, DPM

“All Shoe Fashions From 7 Basic Styles” By William Rossi, DPM The shoe designers are a seemingly bottomless well of creative ingenuity. It's estimated that in the U.S. and Europe alone about 200,000 "new" footwear fashions are introduced each year--a million every five years. While perhaps fewer than 20,000 ever go into actual production each year, it's still a torrent of inventive artistry that seems to have no limits. But few realize that of this super-abundance, all footwear fashion stems from only seven basic shoe styles: the pump, boot, oxford, sandal, clog, mule and moccasin. You might be quick to claim that other basic styles should be added to those seven. But no, they'd prove to be simply adaptations of one of those original seven. For example, sneakers or athletic footwear are merely spinoffs from the oxford. A slingback or strap shoe is a version of the pump. The loafer is a clone of the moccasin. And so on. Now, two very interesting things about those seven basic styles. Not one was originally designed by or for a woman. All began as men's styles and later evolved into women's versions. Second, the "newest" of those seven basics is the oxford, introduced some 350 years ago. Not a single new basic shoe style has been introduced in nearly four centuries. Not one, despite all the creative energies of the designers. Now, right here it's important to distinguish between a style and a fashion. A style is something basic. The word is from the Latin "stylus," a pen-like instrument used to draw an outline or form. -

Magical Clothing Fo R Discerning Adventurers

Magical Clothing fo r Discerning Adventurers Anja Svare Sample file Introduction Table of Contents I really like making magic items. General Clothing 3 Now, there’s nothing wrong with how 5e presents the majority of magic items. But the tend to get a little stale. Potions are all essentially the same, scrolls don’t really have much interest Outerwear 6 other than what spell they contain, you’ve got a few interesting things that aren’t weapons or armor, but that’s about it. Most of those will either break a game because of their power, or Headwear 12 they should require a massive quest of campaign-level, world- spanning heroics to obtain. There just aren’t a lot of items that everyday adventurers want, Footwear 14 that won’t break the bank so to speak, and are things that are actually useful. Everybody wears clothes (I don’t want to think about nude D&D), and everybody loves magic items for their Accessories 16 character.. Combining the two seemed like a good idea, but I didn’t want Special Orders 20 to go with just pants, shirts, etc. I scoured the internet for medieval period clothing, and narrowed down a list of items that were common across a wide range of times and places throughout Europe during the Middle Ages. Now, I did come Glossary 22 across some interesting clothing items that fell outside that range or geography, and a few are included here. None of the items presented here are gender specific. I intentionally left any mention of that out of each item. -

![Eiite States I Atent [19] [1 1] 4,348,822 Lesavage [45] Sep](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0464/eiite-states-i-atent-19-1-1-4-348-822-lesavage-45-sep-1060464.webp)

Eiite States I Atent [19] [1 1] 4,348,822 Lesavage [45] Sep

Eiite States i atent [19] [1 1] 4,348,822 Lesavage [45] Sep. 14, 1932 [54] SNOWSHOE FOOTWEAR Primary Examiner—Patrick D. Lawson Attorney, Agent, or Firm—Stanley G. Ade [76] Inventor: Stephen J. Lesavage, 150 Robindale Rd., Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada, [57] ABSTRACT R3R 1G7 The attachment straps for snowshoes usually require a [2]] Appl. No: 221,926 buckle type strap or tied construction which is difficult to retain over the toe of the boot or shoe during use. [22] Filed: Dec. 31, 1980 Tabs sewn to the side of moccasins are used to retain the straps but these are not usable with other types of foot [30] Foreign Application Priority Data wear such as boots and the like. In one embodiment of Jan. 17, 1980 [CA] Canada ................................. .. 3442l2 the invention, the sole is widened out at the area of strap engagement and provided with vertically situated [51] Int. Cl.3 .............................................. .. A43B 5/04 closed ended slots through which the straps engage thus [52] US. Cl. ....................................... .1 36/122 holding the footwear in the desired position relative to [58] Field of Search ............... .. 36/122, 123, 124, 125, the snowshoe. The preferred embodiment utilizes simi 36/25 R lar slots but opening out onto the periphery of the en [56] References Cited larged sole portion so that the strap can be engaged and disengaged without buckling. This also permits a closed U.S. PATENT DOCUMENTS elasticized strap to be used as it can be engaged and 2,516,238 7/l950 Mortsell .............................. .. 36/122 disengaged and snapped into position over the instep or vamp area of the boot or shoe. -

FIXING YOUR ” After More Than 25 Years of Treating Feet and Reading About Treating Feet, I’Ve Found Nothing, Absolutely Nothing, As Helpful As Fixing Your Feet

“From heels to toes, products to pathology, resources to rehabilitation, this book has it all. An essential guide. — Runner’s World FIXING YOUR ” After more than 25 years of treating feet and reading about treating feet, I’ve found nothing, absolutely nothing, as helpful as Fixing Your Feet. — Buck Tilton, MS, cofounder of the Wilderness Medicine Institute of NOLS and author of many books on outdoor health and safety FIXING YOUR Take Care of Your Feet 7TH Edition Whether you’re hiking, backpacking, running, or walking, your feet FEET take a beating with every step. Don’t wait until foot pain inhibits your speed, strength, and style. Learn the basics and the finer points of FEET foot care before pain becomes a problem. Foot expert and ultrarunner John Vonhof and physical therapist Tonya Olson share how the interplay of anatomy, biomechanics, and footwear can lead to happy (or hurting!) feet. Fixing Your Feet covers all you need to know to care for your feet, right now and miles down the road. Inside You’ll Find Vonhof/Olson • Tried-and-true methods of foot care from numerous experts • Tips and anecdotes about recovery and training • Information about hundreds of foot care products for nearly every foot ailment • High-interest topics such as barefoot running and minimalist footwear, blister prevention, and foot care for athletes • Discussions of individual foot care and team care WILDERNESS PRESS John Vonhof SPORTS/FOOT CARE with Tonya Olson, MSPT, DPT ISBN 978-1-64359-063-9 $21.95 5 2 1 9 5 Injury Prevention and Treatment for People Who Push the Limits of Their Feet 9 781643 590639 Runners, Walkers, Hikers, Climbers, Athletes, Dancers, Soldiers, and More! WILDERNESS PRESS . -

Shoe Constructions

U. S. DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE DANIEL C. ROPER, Secretary NATIONAL BUREAU OF STANDARDS LYMAN J. BRIGGS, Director CIRCULAR OF THE NATIONAL BUREAU OF STANDARDS C419 SHOE CONSTRUCTIONS By Roy C. Bowker eau of Standardt, APR 1 1938 UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE WASHINGTON : 1938 For sale by tlie Superintendent of Documents, Washington, D. C. Price 10 cents PREFACE Shoes are an important item in the budget of every family. Much general information is available concerning shoes and a multiplicity of types can be purchased over a wide price range. However, methods for use in evaluating the quality and performance of shoes are lacking. Research work on shoes is being conducted at the National Bureau of Standards for the purpose of developing quality and performance standards in terms of value to the individual consumer. A part of the problem has to do with the influence of the type of construction on the ability of the shoe to hold its shape under simulated service conditions. This circular presents the results of a study of the different methods of construction in common use. A review of the literature issued by the trade organizations has shown that there are at least 40 types of shoe construction, each of which is described briefly in this circular and listed under 8 main classes. Comments on the performance of shoes and the value to the con¬ sumer of construction identification marks on shoes are included. Lyman J. Briggs, Director. ir SHOE CONSTRUCTIONS By Roy C. Bowker ABSTRACT This circular contains brief descriptions of 40 individual shoe constructions and discusses their classification under 8 main classes; welt, McKay, Littleway, turn, stitchdown, nailed, cemented, and moccasin. -

Footwear News Oct. 2015 Issue

FOOTWEARNEWS.COM / OCTOBER 12, 2015 / @FOOTWEARNEWS WORKBOOT ISSUE OH, BUY THE WAY Infl uential retailers reveal Europe’s hottest shoe fi nds HUNDRED PROOF Where the king of ultra running plans to go next MISSION READY How Rocky Brands helps the military prep for action Spring’s newest workboots are made to last with sleek fi nishes. Here, GOODYEAR builds a hiker high-top hybrid TOUGHthat’s up for any job. LOVES Pause Causefor the Align with FN’s Special Issue: QVC presents FFANY Shoes On Sale Bonus Distribution: QVC presents FFANY Shoes On Sale Event Issue Date 10.19 A PORTION OF ADVERTISING PROCEEDS GO TO QVC/FFANY SHOES ON SALE TO SUPPORT THE FIGHT AGAINST BREAST CANCER THE POWER OF CONTENT FOR ADVERTISING INFORMATION, PLEASE CONTACT LAUREN SCHOR, ASSOCIATE PUBLISHER AT 212 256 8118 OR [email protected] INSIDER 5 Best Buys Top retailers sound off on what clicked for them in Europe. 7 FN Spy An inside look at the starring shoes in Season 4 of “The Mindy Project.” 8 Atwood’s Next Steps The designer on his plans for B Brian Atwood and the expansion he’s eyeing for his main line. 9 What’s Trending Holiday sales fore- casts and Phil Knight’s upcoming memoir. FEATURES 11 Top 20 FN ranks the best of Paris. 16 Iron Man Sleek silhouettes give spring workboots a strong foundation. MARKETPLACE 22 Girl Power Thanks to Moxie Trades, workboots are now made for her. 23 Five Questions Rocky’s military expert weighs in on catering to the armed forces. -

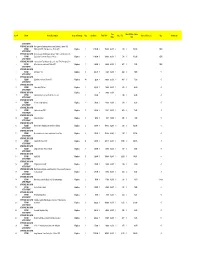

Inventory Example.Xlsx

Tax Total RCV Inc. Sales Item # Room Name/Description Scope of Damage Qty Cost/Item Total RCV Sales Tax Source/Reference Age Comments Rate Tax ATTIC FRONT STORAGE AND GYM New Lego-like building block set from Susengo, Titanic 1912 1 ROOM RMS, Item 0577, 1021 piece set, Photo 8070 Replace 1 $119.99 $ 119.99 6.25% $ 7.50 $ 127.49 NEW ATTIC FRONT STORAGE AND GYM 257 piece Lego building set, Disney's Pixar Toy Story, Item 7593 2 ROOM Buzz's Star Command Ship, new in box Replace 1 $124.99 $ 124.99 6.25% $ 7.81 $ 132.80 NEW ATTIC FRONT STORAGE AND GYM Lego set from Toy Story, 92 piece set, Item 7590, Woody & Buzz 3 ROOM to the Rescue, new in box, Photo 8071 Replace 1 $69.99 $ 69.99 6.25% $ 4.37 $ 74.36 NEW ATTIC FRONT STORAGE AND GYM 4 ROOM US military coin Replace 5 $14.99 $ 74.95 6.25% $ 4.68 $ 79.63 +5 ATTIC FRONT STORAGE AND GYM 5 ROOM US military shirt pin, Photo 8072 Replace 14 $4.99 $ 69.86 6.25% $ 4.37 $ 74.23 +5 ATTIC FRONT STORAGE AND GYM 6 ROOM 3 disc adult DVD set Replace 1 $39.99 $ 39.99 6.25% $ 2.50 $ 42.49 +5 ATTIC FRONT STORAGE AND GYM Replace $ 24.99 6.25% 7 ROOM Adult massager toy from Pearl Sheen series 1 $24.99 $ 1.56 $ 26.55 +5 ATTIC FRONT STORAGE AND GYM 8 ROOM 6' leather whip adult toy Replace 1 $18.99 $ 18.99 6.25% $ 1.19 $ 20.18 +5 ATTIC FRONT STORAGE AND GYM 9 ROOM Adult movie on DVD Replace 3 $24.99 $ 74.97 6.25% $ 4.69 $ 79.66 +5 ATTIC FRONT STORAGE AND GYM 10 ROOM Glass shot glass Replace 3 $2.99 $ 8.97 6.25% $ 0.56 $ 9.53 +5 ATTIC FRONT STORAGE AND GYM 11 ROOM Men's leather banded wrist watch from Disney Replace