Arxiv:1711.00219V2 [Math.OA] 9 Aug 2019 R,Fe Rbblt,Glbr Coefficients

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Math Preliminaries

Preliminaries We establish here a few notational conventions used throughout the text. Arithmetic with ∞ We shall sometimes use the symbols “∞” and “−∞” in simple arithmetic expressions involving real numbers. The interpretation given to such ex- pressions is the usual, natural one; for example, for all real numbers x, we have −∞ < x < ∞, x + ∞ = ∞, x − ∞ = −∞, ∞ + ∞ = ∞, and (−∞) + (−∞) = −∞. Some such expressions have no sensible interpreta- tion (e.g., ∞ − ∞). Logarithms and exponentials We denote by log x the natural logarithm of x. The logarithm of x to the base b is denoted logb x. We denote by ex the usual exponential function, where e ≈ 2.71828 is the base of the natural logarithm. We may also write exp[x] instead of ex. Sets and relations We use the symbol ∅ to denote the empty set. For two sets A, B, we use the notation A ⊆ B to mean that A is a subset of B (with A possibly equal to B), and the notation A ( B to mean that A is a proper subset of B (i.e., A ⊆ B but A 6= B); further, A ∪ B denotes the union of A and B, A ∩ B the intersection of A and B, and A \ B the set of all elements of A that are not in B. For sets S1,...,Sn, we denote by S1 × · · · × Sn the Cartesian product xiv Preliminaries xv of S1,...,Sn, that is, the set of all n-tuples (a1, . , an), where ai ∈ Si for i = 1, . , n. We use the notation S×n to denote the Cartesian product of n copies of a set S, and for x ∈ S, we denote by x×n the element of S×n consisting of n copies of x. -

Sets, Functions

Sets 1 Sets Informally: A set is a collection of (mathematical) objects, with the collection treated as a single mathematical object. Examples: • real numbers, • complex numbers, C • integers, • All students in our class Defining Sets Sets can be defined directly: e.g. {1,2,4,8,16,32,…}, {CSC1130,CSC2110,…} Order, number of occurence are not important. e.g. {A,B,C} = {C,B,A} = {A,A,B,C,B} A set can be an element of another set. {1,{2},{3,{4}}} Defining Sets by Predicates The set of elements, x, in A such that P(x) is true. {}x APx| ( ) The set of prime numbers: Commonly Used Sets • N = {0, 1, 2, 3, …}, the set of natural numbers • Z = {…, -2, -1, 0, 1, 2, …}, the set of integers • Z+ = {1, 2, 3, …}, the set of positive integers • Q = {p/q | p Z, q Z, and q ≠ 0}, the set of rational numbers • R, the set of real numbers Special Sets • Empty Set (null set): a set that has no elements, denoted by ф or {}. • Example: The set of all positive integers that are greater than their squares is an empty set. • Singleton set: a set with one element • Compare: ф and {ф} – Ф: an empty set. Think of this as an empty folder – {ф}: a set with one element. The element is an empty set. Think of this as an folder with an empty folder in it. Venn Diagrams • Represent sets graphically • The universal set U, which contains all the objects under consideration, is represented by a rectangle. -

Center and Composition Conditions for Abel Equation

Center and Comp osition conditions for Ab el Equation Thesis for the degree of Do ctor of Philosophy by Michael Blinov Under the Sup ervision of professor Yosef Yomdin Department of Theoretical Mathematics The Weizmann Institute of Science Submitted to the Feinb erg Graduate Scho ol of the Weizmann Institute of Science Rehovot Israel June Acknowledgments I would like to thank my advisor Professor Yosef Yomdin for his great sup ervision constant supp ort and encouragement for guiding and stimulat ing my mathematical work I should also mention that my trips to scien tic meetings were supp orted from Y Yomdins Minerva Science Foundation grant I am grateful to JP Francoise F Pakovich E Shulman S Yakovenko and V Katsnelson for interesting discussions I thank Carla Scapinello Uruguay Jonatan Gutman Israel Michael Kiermaier Germany and Oleg Lavrovsky Canada for their results obtained during summer pro jects that I sup ervised I am also grateful to my mother for her patience supp ort and lo ve I wish to thank my mathematical teacher V Sap ozhnikov who gave the initial push to my mathematical research Finally I wish to thank the following for their friendship and in some cases love Lili Eugene Bom Elad Younghee Ira Rimma Yulia Felix Eduard Lena Dima Oksana Olga Alex and many more Abstract We consider the real vector eld f x y gx y on the real plane IR This vector eld describ es the dynamical system x f x y y g x y A classical CenterFo cus problem whichwas stated byHPoincare in s is nd conditions on f g under which all tra jectories -

The Structure of the 3-Separations of 3-Connected Matroids

THE STRUCTURE OF THE 3{SEPARATIONS OF 3{CONNECTED MATROIDS JAMES OXLEY, CHARLES SEMPLE, AND GEOFF WHITTLE Abstract. Tutte defined a k{separation of a matroid M to be a partition (A; B) of the ground set of M such that |A|; |B|≥k and r(A)+r(B) − r(M) <k. If, for all m<n, the matroid M has no m{separations, then M is n{connected. Earlier, Whitney showed that (A; B) is a 1{separation of M if and only if A is a union of 2{connected components of M.WhenM is 2{connected, Cunningham and Edmonds gave a tree decomposition of M that displays all of its 2{separations. When M is 3{connected, this paper describes a tree decomposition of M that displays, up to a certain natural equivalence, all non-trivial 3{ separations of M. 1. Introduction One of Tutte’s many important contributions to matroid theory was the introduction of the general theory of separations and connectivity [10] de- fined in the abstract. The structure of the 1–separations in a matroid is elementary. They induce a partition of the ground set which in turn induces a decomposition of the matroid into 2–connected components [11]. Cun- ningham and Edmonds [1] considered the structure of 2–separations in a matroid. They showed that a 2–connected matroid M can be decomposed into a set of 3–connected matroids with the property that M can be built from these 3–connected matroids via a canonical operation known as 2–sum. Moreover, there is a labelled tree that gives a precise description of the way that M is built from the 3–connected pieces. -

Matroids with Nine Elements

Matroids with nine elements Dillon Mayhew School of Mathematics, Statistics & Computer Science Victoria University Wellington, New Zealand [email protected] Gordon F. Royle School of Computer Science & Software Engineering University of Western Australia Perth, Australia [email protected] February 2, 2008 Abstract We describe the computation of a catalogue containing all matroids with up to nine elements, and present some fundamental data arising from this cataogue. Our computation confirms and extends the results obtained in the 1960s by Blackburn, Crapo & Higgs. The matroids and associated data are stored in an online database, arXiv:math/0702316v1 [math.CO] 12 Feb 2007 and we give three short examples of the use of this database. 1 Introduction In the late 1960s, Blackburn, Crapo & Higgs published a technical report describing the results of a computer search for all simple matroids on up to eight elements (although the resulting paper [2] did not appear until 1973). In both the report and the paper they said 1 “It is unlikely that a complete tabulation of 9-point geometries will be either feasible or desirable, as there will be many thousands of them. The recursion g(9) = g(8)3/2 predicts 29260.” Perhaps this comment dissuaded later researchers in matroid theory, because their cata- logue remained unextended for more than 30 years, which surely makes it one of the longest standing computational results in combinatorics. However, in this paper we demonstrate that they were in fact unduly pessimistic, and describe an orderly algorithm (see McKay [7] and Royle [11]) that confirms their computations and extends them by determining the 383172 pairwise non-isomorphic matroids on nine elements (see Table 1). -

Section 3: Equivalence Relations

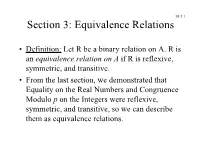

10.3.1 Section 3: Equivalence Relations • Definition: Let R be a binary relation on A. R is an equivalence relation on A if R is reflexive, symmetric, and transitive. • From the last section, we demonstrated that Equality on the Real Numbers and Congruence Modulo p on the Integers were reflexive, symmetric, and transitive, so we can describe them as equivalence relations. 10.3.2 Examples • What is the “smallest” equivalence relation on a set A? R = {(a,a) | a Î A}, so that n(R) = n(A). • What is the “largest” equivalence relation on a set A? R = A ´ A, so that n(R) = [n(A)]2. Equivalence Classes 10.3.3 • Definition: If R is an equivalence relation on a set A, and a Î A, then the equivalence class of a is defined to be: [a] = {b Î A | (a,b) Î R}. • In other words, [a] is the set of all elements which relate to a by R. • For example: If R is congruence mod 5, then [3] = {..., -12, -7, -2, 3, 8, 13, 18, ...}. • Another example: If R is equality on Q, then [2/3] = {2/3, 4/6, 6/9, 8/12, 10/15, ...}. • Observation: If b Î [a], then [b] = [a]. 10.3.4 A String Example • Let S = {0,1} and denote L(s) = length of s, for any string s Î S*. Consider the relation: R = {(s,t) | s,t Î S* and L(s) = L(t)} • R is an equivalence relation. Why? • REF: For all s Î S*, L(s) = L(s); SYM: If L(s) = L(t), then L(t) = L(s); TRAN: If L(s) = L(t) and L(t) = L(u), L(s) = L(u). -

Parity Systems and the Delta-Matroid Intersection Problem

Parity Systems and the Delta-Matroid Intersection Problem Andr´eBouchet ∗ and Bill Jackson † Submitted: February 16, 1998; Accepted: September 3, 1999. Abstract We consider the problem of determining when two delta-matroids on the same ground-set have a common base. Our approach is to adapt the theory of matchings in 2-polymatroids developed by Lov´asz to a new abstract system, which we call a parity system. Examples of parity systems may be obtained by combining either, two delta- matroids, or two orthogonal 2-polymatroids, on the same ground-sets. We show that many of the results of Lov´aszconcerning ‘double flowers’ and ‘projections’ carry over to parity systems. 1 Introduction: the delta-matroid intersec- tion problem A delta-matroid is a pair (V, ) with a finite set V and a nonempty collection of subsets of V , called theBfeasible sets or bases, satisfying the following axiom:B ∗D´epartement d’informatique, Universit´edu Maine, 72017 Le Mans Cedex, France. [email protected] †Department of Mathematical and Computing Sciences, Goldsmiths’ College, London SE14 6NW, England. [email protected] 1 the electronic journal of combinatorics 7 (2000), #R14 2 1.1 For B1 and B2 in and v1 in B1∆B2, there is v2 in B1∆B2 such that B B1∆ v1, v2 belongs to . { } B Here P ∆Q = (P Q) (Q P ) is the symmetric difference of two subsets P and Q of V . If X\ is a∪ subset\ of V and if we set ∆X = B∆X : B , then we note that (V, ∆X) is a new delta-matroid.B The{ transformation∈ B} (V, ) (V, ∆X) is calledB a twisting. -

Computing Partitions Within SQL Queries: a Dead End? Frédéric Dumonceaux, Guillaume Raschia, Marc Gelgon

Computing Partitions within SQL Queries: A Dead End? Frédéric Dumonceaux, Guillaume Raschia, Marc Gelgon To cite this version: Frédéric Dumonceaux, Guillaume Raschia, Marc Gelgon. Computing Partitions within SQL Queries: A Dead End?. 2013. hal-00768156 HAL Id: hal-00768156 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-00768156 Submitted on 20 Dec 2012 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Computing Partitions within SQL Queries: A Dead End? Fr´ed´eric Dumonceaux – Guillaume Raschia – Marc Gelgon December 20, 2012 Abstract The primary goal of relational databases is to provide efficient query processing on sets of tuples and thereafter, query evaluation and optimization strategies are a key issue in database implementation. Producing universally fast execu- tion plans remains a challenging task since the underlying relational model has a significant impact on algebraic definition of the operators, thereby on their implementation in terms of space and time complexity. At least, it should pre- vent a quadratic behavior in order to consider scaling-up towards the processing of large datasets. The main purpose of this paper is to show that there is no trivial relational modeling for managing collections of partitions (i.e. -

Partial Ordering Relations • a Relation Is Said to Be a Partial Ordering Relation If It Is Reflexive, Anti -Symmetric, and Transitive

Relations Chang-Gun Lee ([email protected]) Assistant Professor The School of Computer Science and Engineering Seoul National University Relations • The concept of relations is also commonly used in computer science – two of the programs are related if they share some common data and are not related otherwise. – two wireless nodes are related if they interfere each other and are not related otherwise – In a database, two objects are related if their secondary key values are the same • What is the mathematical definition of a relation? • Definition 13.1 (Relation): A relation is a set of ordered pairs – The set of ordered pairs is a complete listing of all pairs of objects that “satisfy” the relation •Examples: – Greater Than Re lat ion = {(2 {(21)(31)(32),1), (3,1), (3,2), ...... } – R = {(1,2), (1,3), (3,0)} (1,2)∈ R, 1 R 2 :"x is related by the relation R to y" Relations • Definition 13.2 (Relation on, between sets) Let R be a relation and let A and B be sets . –We say R is a relation on A provided R ⊆ A× A –We say R is a relation from A to B provided R ⊆ A× B Example Relations •Let A={1,2,3,4} and B={4,5,6,7}. Let – R={(11)(22)(33)(44)}{(1,1),(2,2),(3,3),(4,4)} – S={(1,2),(3,2)} – T={(1,4),(1,5),(4,7)} – U={(4,4),(5,2),(6,2),(7,3)}, and – V={(1,7),(7,1)} • All of these are relations – R is a relation on A. -

Notes for Math 450 Lecture Notes 2

Notes for Math 450 Lecture Notes 2 Renato Feres 1 Probability Spaces We first explain the basic concept of a probability space, (Ω, F,P ). This may be interpreted as an experiment with random outcomes. The set Ω is the collection of all possible outcomes of the experiment; F is a family of subsets of Ω called events; and P is a function that associates to an event its probability. These objects must satisfy certain logical requirements, which are detailed below. A random variable is a function X :Ω → S of the output of the random system. We explore some of the general implications of these abstract concepts. 1.1 Events and the basic set operations on them Any situation where the outcome is regarded as random will be referred to as an experiment, and the set of all possible outcomes of the experiment comprises its sample space, denoted by S or, at times, Ω. Each possible outcome of the experiment corresponds to a single element of S. For example, rolling a die is an experiment whose sample space is the finite set {1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6}. The sample space for the experiment of tossing three (distinguishable) coins is {HHH,HHT,HTH,HTT,THH,THT,TTH,TTT } where HTH indicates the ordered triple (H, T, H) in the product set {H, T }3. The delay in departure of a flight scheduled for 10:00 AM every day can be regarded as the outcome of an experiment in this abstract sense, where the sample space now may be taken to be the interval [0, ∞) of the real line. -

Equivalence Relation and Partitions

Regular Expressions [1] Equivalence relation and partitions An equivalence relation on a set X is a relation which is reflexive, symmetric and transitive A partition of a set X is a set P of cells or blocks that are subsets of X such that 1. If C ∈ P then C 6= ∅ 2. If C1,C2 ∈ P and C1 6= C2 then C1 ∩ C2 = ∅ 3. If a ∈ X there exists C ∈ P such that a ∈ C 1 Regular Expressions [2] Equivalence relation and partitions If R is an equivalence relation on X, we define the equivalence class of a ∈ X to be the set [a] = {b ∈ X | R(a, b)} Lemma: [a] = [b] iff R(a, b) Theorem: The set of all equivalence classes form a partition of X We write X/R this set of equivalence classes Example: X is the set of all integers, and R(x, y) is the relation “3 divides x − y”. Then X/R has 3 elements 2 Regular Expressions [3] Equivalence Relations Example: on X = {1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10} the relation x ≡ y defined by 3 divides x − y is an equivalence relation We can now form X/≡ which is the set of all equivalence classes [1] = [4] = {1, 4, 7, 10} [2] = [8] = {2, 5, 8} [3] = {3, 6, 9} This set is the quotient of X by the relation ≡ 3 Regular Expressions [4] Equivalence relations on states A = (Q, Σ, δ, q0,F ) is a DFA If R is an equivalence relation on Q, we say that R is compatible with A iff (1) R(q1, q2) implies R(δ(q1, a), δ(q2, a)) for all a ∈ Σ (2) R(q1, q2) and q1 ∈ F implies q2 ∈ F 4 Regular Expressions [5] Equivalence relations on states (1) means that if q1, q2 are in the same block then so are q1.a and q2.a and this for all a in Σ (2) says that F can be written as an union of some blocks We can then define δ/R([q], a) = [q.a] and [q] ∈ F/R iff q ∈ F 5 Regular Expressions [6] Equivalence relations on states Theorem: If R is a compatible equivalence relation on A then we can consider the DFA A/R = (Q/R, Σ, δ/R.[q0], F/R) and we have L(A/R) = L(A) Proof: By induction on x we have δˆ([q], x) = [δˆ(q, x)] and then [q0].x ∈ F/R iff q0.x ∈ F Notice that A/R has fewer states than A 6 Regular Expressions [7] Equivalence of States Theorem: Let A = (Q, Σ, δ, q0,F ) be a DFA. -

Dynatomic Polynomials, Necklace Operators, and Universal Relations for Dynamical Units

DYNATOMIC POLYNOMIALS, NECKLACE OPERATORS, AND UNIVERSAL RELATIONS FOR DYNAMICAL UNITS JOHN R. DOYLE, PAUL FILI, AND TREVOR HYDE 1. INTRODUCTION Let f(x) 2 K[x] be a polynomial with coefficients in a field K. For an integer k ≥ 0, we denote by f k(x) the k-fold iterated composition of f with itself. The dth dynatomic polynomial Φf;d(x) 2 K[x] of f is defined by the product Y d=e µ(e) Φf;d(x) := (f (x) − x) ; ejd where µ is the standard number-theoretic Möbius function on N. We refer the reader to [12, §4.1] for background on dynatomic polynomials. For generic f(x), the dth dynatomic polyno- mial Φf;d(x) vanishes at precisely the periodic points of f with primitive period d. In this paper we consider the polynomial equation Φf;d(x) = 1 and show that it often has f-preperiodic solu- tions determined by arithmetic properties of d, independent of f. Moreover, these f-preperiodic solutions are detected by cyclotomic factors of the dth necklace polynomial: 1 X M (x) = µ(e)xd=e 2 [x]: d d Q ejd Our results extend earlier work of Morton and Silverman [8], but our techniques are quite dif- ferent and apply more broadly. We begin by recalling some notation and terminology. The cocore of a positive integer d is d=d0 where d0 is the largest squarefree factor of d. If m ≥ 0 and n ≥ 1, then the (m; n)th generalized dynatomic polynomial Φf;m;n(x) of f(x) is defined by Φf;0;n(x) := Φf;n(x) and m Φf;n(f (x)) Φf;m;n(x) := m−1 Φf;n(f (x)) for m ≥ 1.