We Are Very Pleased for You to Have a Copy of This Article, Which You May Read, Print Or Save on Your Computer

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Elegies for Cello and Piano by Bridge, Britten and Delius: a Study of Traditions and Influences

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Theses and Dissertations--Music Music 2012 Elegies for Cello and Piano by Bridge, Britten and Delius: A Study of Traditions and Influences Sara Gardner Birnbaum University of Kentucky, [email protected] Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Birnbaum, Sara Gardner, "Elegies for Cello and Piano by Bridge, Britten and Delius: A Study of Traditions and Influences" (2012). Theses and Dissertations--Music. 7. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/music_etds/7 This Doctoral Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Music at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations--Music by an authorized administrator of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STUDENT AGREEMENT: I represent that my thesis or dissertation and abstract are my original work. Proper attribution has been given to all outside sources. I understand that I am solely responsible for obtaining any needed copyright permissions. I have obtained and attached hereto needed written permission statements(s) from the owner(s) of each third-party copyrighted matter to be included in my work, allowing electronic distribution (if such use is not permitted by the fair use doctrine). I hereby grant to The University of Kentucky and its agents the non-exclusive license to archive and make accessible my work in whole or in part in all forms of media, now or hereafter known. I agree that the document mentioned above may be made available immediately for worldwide access unless a preapproved embargo applies. -

Delius Monument Dedicatedat the 23Rd Annual Festival by Thomas Hilton Gunn

The Delius SocieQ JOUrnAtT7 Summer/Autumn1992, Number 109 The Delius Sociefy Full Membershipand Institutionsf 15per year USA and CanadaUS$31 per year Africa,Australasia and Far East€18 President Eric FenbyOBE, Hon D Mus.Hon D Litt. Hon RAM. FRCM,Hon FTCL VicePresidents FelixAprahamian Hon RCO Roland Gibson MSc, PhD (FounderMember) MeredithDavies CBE, MA. B Mus. FRCM, Hon RAM Norman Del Mar CBE. Hon D Mus VernonHandley MA, FRCM, D Univ (Surrey) Sir CharlesMackerras CBE Chairman R B Meadows 5 WestbourneHouse. Mount ParkRoad. Harrow. Middlesex HAI 3JT Ti,easurer [to whom membershipenquiries should be directed] DerekCox Mercers,6 Mount Pleasant,Blockley, Glos. GL56 9BU Tel:(0386) 700175 Secretary@cting) JonathanMaddox 6 Town Farm,Wheathampstead, Herts AL4 8QL Tel: (058-283)3668 Editor StephenLloyd 85aFarley Hill. Luton. BedfordshireLul 5EG Iel: Luton (0582)20075 CONTENTS 'The others are just harpers . .': an afternoon with Sidonie Goossens by StephenLloyd.... Frederick Delius: Air and Dance.An historical note by Robert Threlfall.. BeatriceHarrison and Delius'sCello Music by Julian Lloyd Webber.... l0 The Delius Monument dedicatedat the 23rd Annual Festival by Thomas Hilton Gunn........ t4 Fennimoreancl Gerda:the New York premidre............ l1 -Opera A Village Romeo anrl Juliet: BBC2 Season' by Henry Gi1es......... .............18 Record Reviews Paris eIc.(BSO. Hickox) ......................2l Sea Drift etc. (WNOO. Mackerras),.......... ...........2l Violin Concerto etc.(Little. WNOOO. Mackerras)................................22 Violin Concerto etc.(Pougnet. RPO. Beecham) ................23 Hassan,Sea Drift etc. (RPO. Beecham) . .-................25 THE HARRISON SISTERS Works by Delius and others..............26 A Mu.s:;r1/'Li.fe at the Brighton Festival ..............27 South-WestBranch Meetinss.. ........30 MicllanclsBranch Dinner..... ............3l Obittrary:Sir Charles Groves .........32 News Round-Up ...............33 Correspondence....... -

May Harrison Biografie

Harrison, May May Harrison Biografie * 23. August 1890 in Roorkäa, Indien May Harrison wurde am 28. August 1890 als erste von † 8. Juni 1959 in South Nutfield (Surrey), England insgesamt vier Kindern geboren. Der Vater, J. H. C. Har- rison, war zu dieser Zeit als Colonel der Royal Engineers Violinistin, Solistin, Kammermusikerin, Dozentin für in Roorkäa, Indien, stationiert. Als May Harrison zwei Violine, Klavierbegleiterin, Konzertveranstalterin, Jahre alt war, kehrte die Familie nach England zurück. Komponistin (?) Die Mutter Anne Harrison war Sängerin und Pianistin und sorgte für eine fundierte musikalische Ausbildung ih- „Miss Harrison plays with a confidence and decision rer Töchter, von denen drei professionelle Musikerinnen which carries her audience with her from the very first. wurden: May Harrison und Margaret Harrison (geb. She has the orator’s instinct for taking captive the sympa- 1899) als Violinistinnen und Klavierbegleiterinnen, Beat- thies of those whom she is addressing. But she does not rice Harrison (geb. 1892) als Cellistin. Von klein auf er- allow herself to be carried away. Her performance is accu- hielt May Harrison Unterricht in Violine und Klavier und rate and conscientious.” gewann bereits im Alter von 10 Jahren die „Associated „Miss Harrison spielt mit einem Selbstvertrauen und ei- Board’s gold medal“ in der „Senior Devision“, wobei sie ner Entschiedenheit, die das Publikum vom ersten Mo- sich gegen 3000 Mitbewerber durchsetzte. Ein Jahr spä- ment an trägt. Sie hat ein Gespür dafür, die Aufmerksam- ter, mit 11 Jahren, wurde May Harrison am Londoner keit jener zu fesseln, an die sie sich wendet. Sie selbst läs- Royal College of Music aufgenommen, erhielt ein Stipen- st sich dabei nicht gehen. -

Harold Tichenor 4/3-2016 Dear Fellow Reel to Reel Audiophie

Harold Tichenor 4/3-2016 Dear fellow reel to reel audiophie: I do hope this email gets through to you as I want to let my past reel to reel customers know the new arrangements for acquiring 15 IPS copies of my tape masters. For the last few years I made them principally available through eBay where Deborah Gunn, better known as Reel-Lady, acted as my agent. Both Deb and I were happy with that arrangement and I can’t thank her enough for her valiant efforts to handle all sales professionally and promptly. However, over the past two years changes at eBay have led to prohibitively high listing and closing costs, even to the point that they take a commission on the shipping costs. During the past year there has also been a flood of lower quality tapes coming onto eBay, many made from cd originals or other dubious sources. It just became impossible to produce our high quality tapes at the net return after eBay and Paypal fees were deducted. Deb and I have talked about it quite a lot and looked at alternative ways to make the tapes available. In the end, Deb decided to retire from the master tape sales business. After giving thought to using eBay myself, setting up a website store or engaging another web sales agent, I decided that I would contact you all directly and test the waters on direct sales to my past customers. Thus this email to you directy from me. FIRST: let me say if you would rather not receive these direct emails in future please let me know immediately and I will remove you from the mailing list. -

String Quartet in E Minor, Op 83

String Quartet in E minor, op 83 A quartet in three movements for two violins, viola and cello: 1 - Allegro moderato; 2 - Piacevole (poco andante); 3 - Allegro molto. Approximate Length: 30 minutes First Performance: Date: 21 May 1919 Venue: Wigmore Hall, London Performed by: Albert Sammons, W H Reed - violins; Raymond Jeremy - viola; Felix Salmond - cello Dedicated to: The Brodsky Quartet Elgar composed two part-quartets in 1878 and a complete one in 1887 but these were set aside and/or destroyed. Years later, the violinist Adolf Brodsky had been urging Elgar to compose a string quartet since 1900 when, as leader of the Hallé Orchestra, he performed several of Elgar's works. Consequently, Elgar first set about composing a String Quartet in 1907 after enjoying a concert in Malvern by the Brodsky Quartet. However, he put it aside when he embarked with determination on his long-delayed First Symphony. It appears that the composer subsequently used themes intended for this earlier quartet in other works, including the symphony. When he eventually returned to the genre, it was to compose an entirely fresh work. It was after enjoying an evening of chamber music in London with Billy Reed’s quartet, just before entering hospital for a tonsillitis operation, that Elgar decided on writing the quartet, and he began it whilst convalescing, completing the first movement by the end of March 1918. He composed that first movement at his home, Severn House, in Hampstead, depressed by the war news and debilitated from his operation. By May, he could move to the peaceful surroundings of Brinkwells, the country cottage that Lady Elgar had found for them in the depth of the Sussex countryside. -

Tertis's Viola Version of Elgar's Cello Concerto by Anthony Addison Special to Clevelandclassical

Preview Heights Chamber Orchestra conductor's notes: Tertis's viola version of Elgar's Cello Concerto by Anthony Addison Special to ClevelandClassical An old adage suggested that violists were merely vio- linists-in-decline. That was before Lionel Tertis! He was born in 1876 of musical parents who had come to England from Poland and Russia and, at three years old, he started playing the piano. At six he performed in public, but had to be locked in a room to make him practice, a procedure that has actually fostered many an international virtuoso. At thirteen, with the agree- ment of his parents, he left home to earn his living in music playing in pickup groups at summer resorts, accompanying a violinist, and acting as music attendant at a lunatic asylum. +41:J:-:/1?<1>95@@1041?@A0510-@(>5:5@E;88131;2!A?5/@-75:3B5;85:-?45? "second study," but concentrating on the piano and playing concertos with the school or- chestra. As sometime happens, his violin teacher showed little interest in a second study <A<58-:01B1:@;8045?2-@41>@4-@41C-?.1@@1>J@@102;>@413>;/1>E@>-01 +5@4?A/4 encouragement, Tertis decided he had to teach himself. Fate intervened when fellow stu- dents wanted to form a string quartet. Tertis volunteered to play viola, borrowed an in- strument, loved the rich quality of its lowest string and thereafter turned the old adage up- side down: a not very obviously gifted violinist becoming a world class violist. But, until the viola attained respectability in Tertis’s hands, composers were reluctant to write for the instrument. -

A Culture of Recording: Christopher Raeburn and the Decca Record Company

A Culture of Recording: Christopher Raeburn and the Decca Record Company Sally Elizabeth Drew A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Sheffield Faculty of Arts and Humanities Department of Music This work was supported by the Arts & Humanities Research Council September 2018 1 2 Abstract This thesis examines the working culture of the Decca Record Company, and how group interaction and individual agency have made an impact on the production of music recordings. Founded in London in 1929, Decca built a global reputation as a pioneer of sound recording with access to the world’s leading musicians. With its roots in manufacturing and experimental wartime engineering, the company developed a peerless classical music catalogue that showcased technological innovation alongside artistic accomplishment. This investigation focuses specifically on the contribution of the recording producer at Decca in creating this legacy, as can be illustrated by the career of Christopher Raeburn, the company’s most prolific producer and specialist in opera and vocal repertoire. It is the first study to examine Raeburn’s archive, and is supported with unpublished memoirs, private papers and recorded interviews with colleagues, collaborators and artists. Using these sources, the thesis considers the history and functions of the staff producer within Decca’s wider operational structure in parallel with the personal aspirations of the individual in exerting control, choice and authority on the process and product of recording. Having been recruited to Decca by John Culshaw in 1957, Raeburn’s fifty-year career spanned seminal moments of the company’s artistic and commercial lifecycle: from assisting in exploiting the dramatic potential of stereo technology in Culshaw’s Ring during the 1960s to his serving as audio producer for the 1990 The Three Tenors Concert international phenomenon. -

Vol. 17, No. 3 December 2011

Journal December 2011 Vol.17, No. 3 The Elgar Society Journal The Society 18 Holtsmere Close, Watford, Herts., WD25 9NG Email: [email protected] December 2011 Vol. 17, No. 3 President Editorial 3 Julian Lloyd Webber FRCM Gerald Lawrence, Elgar and the missing Beau Brummel Music 4 Vice-Presidents Robert Kay Ian Parrott Sir David Willcocks, CBE, MC Elgar and Rosa Newmarch 29 Diana McVeagh Martin Bird Michael Kennedy, CBE Michael Pope Book reviews Sir Colin Davis, CH, CBE Robert Anderson, Martin Bird, Richard Wiley 41 Dame Janet Baker, CH, DBE Leonard Slatkin Music reviews 46 Sir Andrew Davis, CBE Simon Thompson Donald Hunt, OBE Christopher Robinson, CVO, CBE CD reviews 49 Andrew Neill Barry Collett, Martin Bird, Richard Spenceley Sir Mark Elder, CBE 100 Years Ago 61 Chairman Steven Halls Vice-Chairman Stuart Freed Treasurer Peter Hesham Secretary The Editor does not necessarily agree with the views expressed by contributors, Helen Petchey nor does the Elgar Society accept responsibility for such views. Front Cover: Gerald Lawrence in his Beau Brummel costume, from Messrs. William Elkin's published piano arrangement of the Minuet (Arthur Reynolds Collection). Notes for Contributors. Please adhere to these as far as possible if you deliver writing (as is much preferred) in Microsoft Word or Rich Text Format. A longer version is available in case you are prepared to do the formatting, but for the present the editor is content to do this. Copyright: it is the contributor’s responsibility to be reasonably sure that copyright permissions, if Editorial required, are obtained. Illustrations (pictures, short music examples) are welcome, but please ensure they are pertinent, cued into the text, and have captions. -

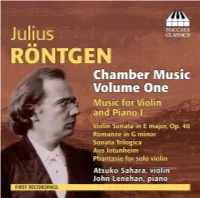

Toccata Classics TOCC0024 Notes

P JULIUS RÖNTGEN, CHAMBER MUSIC, VOLUME ONE – WORKS FOR VIOLIN AND PIANO I by Malcolm MacDonald Considering his prominence in the development of Dutch concert music, and that he was considered by many of his most distinguished contemporaries to possess a compositional talent bordering on genius, the neglect that enveloped the huge output of Julius Röntgen for nearly seventy years after his death seems well-nigh inexplicable, or explicable only to the kind of aesthetic view that had heard of him as stylistically conservative, and equated conservatism as uninteresting and therefore not worth investigating. The recent revival of interest in his works has revealed a much more complex picture, which may be further filled in by the contents of the present CD. A distant relative of the physicist Conrad Röntgen,1 the discoverer of X-rays, Röntgen was born in 1855 into a highly musical family in Leipzig, a city with a musical tradition that stretched back to J. S. Bach himself in the first half of the eighteenth century, and that had been a byword for musical excellence and eminence, both in performance and training, since Mendelssohn’s directorship of the Gewandhaus Orchestra and the Leipzig Conservatoire in the 1830s and ’40s. Röntgen’s violinist father Engelbert, originally from Deventer in the Netherlands, was a member of the Gewandhaus Orchestra and its concert-master from 1873. Julius’ German mother was the pianist Pauline Klengel, sister of the composer Julius Klengel (father of the cellist-composer of the same name), who became his nephew’s principal tutor; the whole family belonged to the circle around the composer and conductor Heinrich von Herzogenberg and his wife Elisabet, whose twin passions were the revival of works by Bach and the music of their close friend Johannes Brahms. -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Season

Mffi — - ,„ :{ ^. ;/j ' "'^/FWS5Sj_£gj. QUADRUM The Mali. At Chkstnut Hill 617-965-5555 Seiji Ozawa, Music Director Carl St. Clair and Pascal Verrot, Assistant Conductors One Hundred and Eighth Season, 1988-89 Trustees of the Boston Symphony Orchestra, Inc. Nelson J. Darling, Jr., Chairman George H. Kidder, President J. P. Barger, Vice-Chairman Mrs. Lewis S. Dabney, Vice-Chairman Archie C. Epps, Vice-Chairman William J. Poorvu, Vice-Chairman and Treasurer Vernon R. Alden Mrs. Eugene B. Doggett Mrs. Robert B. Newman David B. Arnold, Jr. Mrs. John H. Fitzpatrick Peter C. Read Mrs. Norman L. Cahners Avram J. Goldberg Richard A. Smith James F. Cleary Mrs. John L. Grandin Ray Stata Julian Cohen Francis W. Hatch, Jr. William F. Thompson William M. Crozier, Jr. Harvey Chet Krentzman Nicholas T. Zervas Mrs. Michael H. Davis Mrs. August R. Meyer Trustees Emeriti Philip K. Allen E. Morton Jennings, Jr. Mrs. George R. Rowland Allen G. Barry Edward M. Kennedy Mrs. George Lee Sargent Leo L. Beranek Albert L. Nickerson Sidney Stoneman Mrs. John M. Bradley Thomas D. Perry, Jr. John Hoyt Stookey Abram T. Collier Irving W. Rabb John L. Thorndike Mrs. Harris Fahnestock Other Officers of the Corporation John Ex Rodgers, Assistant Treasurer Jay B. W&iles, Assistant Treasurer Daniel R. Gustin, Clerk Administration Kenneth Haas, Managing Director Daniel R. Gustin, Assistant Managing Director and Manager of Tanglewood Michael G. McDonough, Director of Finance and Business Affairs Anne H. Parsons, Orchestra Manager Costa Pilavachi, Artistic Administrator Caroline Smedvig, Director of Promotion Josiah Stevenson, Director of Development Robert Bell, Data Processing Manager Marc Mandel, Publications Coordinator Helen P. -

BRITISH and COMMONWEALTH CONCERTOS from the NINETEENTH CENTURY to the PRESENT Sir Edward Elgar

BRITISH AND COMMONWEALTH CONCERTOS FROM THE NINETEENTH CENTURY TO THE PRESENT A Discography of CDs & LPs Prepared by Michael Herman Sir Edward Elgar (1857-1934) Born in Broadheath, Worcestershire, Elgar was the son of a music shop owner and received only private musical instruction. Despite this he is arguably England’s greatest composer some of whose orchestral music has traveled around the world more than any of his compatriots. In addition to the Conceros, his 3 Symphonies and Enigma Variations are his other orchestral masterpieces. His many other works for orchestra, including the Pomp and Circumstance Marches, Falstaff and Cockaigne Overture have been recorded numerous times. He was appointed Master of the King’s Musick in 1924. Piano Concerto (arranged by Robert Walker from sketches, drafts and recordings) (1913/2004) David Owen Norris (piano)/David Lloyd-Jones/BBC Concert Orchestra ( + Four Songs {orch. Haydn Wood}, Adieu, So Many True Princesses, Spanish Serenade, The Immortal Legions and Collins: Elegy in Memory of Edward Elgar) DUTTON EPOCH CDLX 7148 (2005) Violin Concerto in B minor, Op. 61 (1909-10) Salvatore Accardo (violin)/Richard Hickox/London Symphony Orchestra ( + Walton: Violin Concerto) BRILLIANT CLASSICS 9173 (2010) (original CD release: COLLINS CLASSICS COL 1338-2) (1992) Hugh Bean (violin)/Sir Charles Groves/Royal Liverpool Philharmonic Orchestra ( + Violin Sonata, Piano Quintet, String Quartet, Concert Allegro and Serenade) CLASSICS FOR PLEASURE CDCFP 585908-2 (2 CDs) (2004) (original LP release: HMV ASD2883) (1973) -

William Henry Squire's Out-Of-Print Works for Cello and Piano

PEZZOLI, GINA ANNALISE. D.M.A. William Henry Squire’s Out-of-Print Works for Cello and Piano: Analysis and Suggestions for Teachers (2011). Directed by Dr. Alexander Ezerman. 39 pp. This study presents a biographical overview of William Henry Squire’s life, performance, and teaching career and a pedagogical analysis of his out-of-print works for cello and piano. The study is organized into two main parts. The first reviews Squire’s career as a cellist and composer, with special emphasis on his performing and teaching careers. The second part consists of a detailed description of nine of Squire’s forgotten and out-of-print works for cello and piano. This section includes discussion of the technical and musical challenges of the works, most of which are completely unknown to cellists today. As with many of Squire’s better-known works, these pieces are excellent for intermediate-level cello students. The document is intended to be a teaching “menu” of sorts which details the attributes of each work; therefore the catalogue is organized by difficulty, not by opus number. The nine works chosen for this study are Squire’s Chant D’Amour , Gondoliera , Souvenir, Légende, Berceuse, Slumber Song/Entr’acte, Sérénade op. 15 , Gavotte Humoristique op. 6, and Meditation in C op. 25. WILLIAM HENRY SQUIRE’S OUT-OF-PRINT WORKS FOR CELLO AND PIANO: ANALYSIS AND SUGGESTIONS FOR TEACHERS by Gina Annalise Pezzoli A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of The Graduate School at The University of North Carolina at Greensboro in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Musical Arts Greensboro 2011 Approved by Alex Ezerman Committee Chair © 2011 by Gina Annalise Pezzoli APPROVAL PAGE This dissertation has been approved by the following committee of the Faculty of The Graduate School at The University of North Carolina at Greensboro.