Msc. Agric. Thesis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Backyard June/July 2018

Volume 13, Number 3 Backyard June/July 2018 PoultryAmerica's Favorite Poultry Magazine HELP YOUR CHICKENS maintain a healthy digestive system DIY COOP WATERING with rainwater TIPS TO KEEP YOUR CHICKENS HAPPY while you're on vacation PatrioticHISTORY & Poultry: BREEDS $5.99 U.S. www.countrysidenetwork.com PLUS: CHICKEN CAESAR SALAD, make classic or pesto Backyard Poultry FP 6-16 THINK:Mother Earth 4.5 x7 6/30/16 3:51 PM Page 1 SATISFACTION $ 95 19 EACH –––––––––––––– FREE SHIPPING GUARANTEED When you buy 4 lights or more oryourmoney –––––––––––––– back! PROMO CODE 4FREE To Protect Your Property From Night Predator Animals Nite•Guard Solar® has been proven effective in repelling predator animals for the past 19 years. #1 Nite•Guard Solar attacks the deepest most primal The World’s fear of night animals, that of being discovered. Top Selling Solar Powered Nite•Guard When the sun goes down, Nite•Guard begins to Security System Repellent Tape DON’T BE FOOLED BY Keeps predators flash and continues until sunrise. The simple away during the but effective fact is that a “flash of light” is COPY CATS daylight hours sensed as an eye and becomes an immediate $ 95 14 Per Roll threat to the most ferocious night animals and they will run away. PO Box 274 • Princeton MN 55371 • 1.800.328.6647 ......................... For information and videos, see us at FAMILY OWNED AND OPERATED SINCE 1997 www.niteguard.com ......................... Backyard Poultry FP 6-16 THINK:Mother Earth 4.5 x7 6/30/16 3:51 PM Page 1 SATISFACTION $ 95 19 EACH –––––––––––––– FREE SHIPPING GUARANTEED When you buy 4 lights or more oryourmoney –––––––––––––– back! PROMO CODE 4FREE To Protect Your Property From Night Predator Animals Nite•Guard Solar® has been proven effective in repelling predator animals for the past 19 years. -

2017 Breed Guide Ducks Turkeys Chicks

Turkeys 2017 Breed Guide chickens • ducks • turkeys BLUE SLATE TURKEY BRONZE TURKEY LARGE WHITE TURKEY Chicks Main Use: Ornamental/Meat Production Main Use: Meat Production Main Use: Meat Production Egg Production: Poor Egg Production: Poor Egg Production: Poor Egg Color: Off-White Egg Color: Off-White Egg Color: Off-White Considered a rare breed of Turkey, past The Bronze Broad Breasted Turkey is considered The White Broad Breasted Turkey is the most breeding is thought to be derived from the by some to be the largest and heaviest of the common of commercial broad breasted strains AUSTRA WHITE Spanish Black Turkey of USA and the Norfolk Turkey variety. The Bronze strain is an American of eating Turkeys on the market today. Black in England. origination. An excellent turkey to raise for family Main Use: Egg/Meat Production meat production and has an excellent feed to The White Broad Breasted Turkey is also one Egg Production: Good The Blue Slate Turkey makes an excellent meat conversion rate. However, they will have a of the largest of the breeds and generally are Egg Color: White / Cream BARRED ROCK BLACK AUSTRALORP forager and backyard/farm turkey. They are shorter natural life span than a heritage turkey not able to reproduce very well. They have an The Austra White is a cross between a Black capable of reproducing naturally and do go and have a generally very poor reproduction rate excellent feed to meat conversion ratio. Egg/Meat Production Egg / Meat Production Australorp rooster and a White Leghorn hen. Main Use: Main Use: broody. -

2019-Catalog.Pdf

Email: [email protected] Phone: (814) 495-8057 or (814) 539-7026 Fax: (814) 495-8174 www.myerspoultry.com NPIP 23-524 2019 PRICE LIST Prices are subject to change without notice and do not include shipping and handling charges. We offer a variety of breeds to choose from while trying to keep prices reasonable. If a breed you’re interested in purchasing is not listed, call for availability and prices. HEAVY WHITE CORNISH CROSS BROILER S EX 1-10 11-24 25-49 50-99 100-299 300+ St. Run 2.35 2.05 1.71 1.52 1.31 call for Females 2.35 2.10 1.85 1.48 1.23 pricing Males 2.45 2.25 1.90 1.69 1.60 Coccidiosis Vaccine: .20 per chick only offering this option with the Heavy White Cornish Cross chicks when shipping by themselves. High Yield Broad Breasted Cornish Cross breed that makes great fryers (broilers) and roasters because of the weights that can be achieved. This breed has an excellent feed conversion, livability, strong legs, and a maximum white meat yield with a plump full confirmation. At 6 to 8 weeks of age processed weights of 4 ½ to 6 lbs. can be obtained. Higher weights can be obtained depending on the final grow out duration. With using a well-managed care and feeding program, customers have achieved processed weights of 10 to 14 lb. roasters and capons within 10 to 14 weeks. This breed Wrapped Heavy Cornish is also use for Cornish-Poussins (French for young chicken) 28 to 31 days will yield a Processed 5.25 lbs. -

Animal Genetic Resources Information Bulletin

The designations employed and the presentation of material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Les appellations employées dans cette publication et la présentation des données qui y figurent n’impliquent de la part de l’Organisation des Nations Unies pour l’alimentation et l’agriculture aucune prise de position quant au statut juridique des pays, territoires, villes ou zones, ou de leurs autorités, ni quant au tracé de leurs frontières ou limites. Las denominaciones empleadas en esta publicación y la forma en que aparecen presentados los datos que contiene no implican de parte de la Organización de las Naciones Unidas para la Agricultura y la Alimentación juicio alguno sobre la condición jurídica de países, territorios, ciudades o zonas, o de sus autoridades, ni respecto de la delimitación de sus fronteras o límites. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. Applications for such permission, with a statement of the purpose and the extent of the reproduction, should be addressed to the Director, Information Division, Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, Viale delle Terme di Caracalla, 00100 Rome, Italy. Tous droits réservés. Aucune partie de cette publication ne peut être reproduite, mise en mémoire dans un système de recherche documentaire ni transmise sous quelque forme ou par quelque procédé que ce soit: électronique, mécanique, par photocopie ou autre, sans autorisation préalable du détenteur des droits d’auteur. -

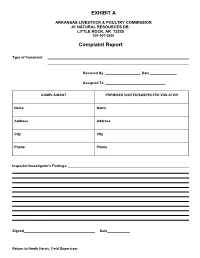

Complaint Report

EXHIBIT A ARKANSAS LIVESTOCK & POULTRY COMMISSION #1 NATURAL RESOURCES DR. LITTLE ROCK, AR 72205 501-907-2400 Complaint Report Type of Complaint Received By Date Assigned To COMPLAINANT PREMISES VISITED/SUSPECTED VIOLATOR Name Name Address Address City City Phone Phone Inspector/Investigator's Findings: Signed Date Return to Heath Harris, Field Supervisor DP-7/DP-46 SPECIAL MATERIALS & MARKETPLACE SAMPLE REPORT ARKANSAS STATE PLANT BOARD Pesticide Division #1 Natural Resources Drive Little Rock, Arkansas 72205 Insp. # Case # Lab # DATE: Sampled: Received: Reported: Sampled At Address GPS Coordinates: N W This block to be used for Marketplace Samples only Manufacturer Address City/State/Zip Brand Name: EPA Reg. #: EPA Est. #: Lot #: Container Type: # on Hand Wt./Size #Sampled Circle appropriate description: [Non-Slurry Liquid] [Slurry Liquid] [Dust] [Granular] [Other] Other Sample Soil Vegetation (describe) Description: (Place check in Water Clothing (describe) appropriate square) Use Dilution Other (describe) Formulation Dilution Rate as mixed Analysis Requested: (Use common pesticide name) Guarantee in Tank (if use dilution) Chain of Custody Date Received by (Received for Lab) Inspector Name Inspector (Print) Signature Check box if Dealer desires copy of completed analysis 9 ARKANSAS LIVESTOCK AND POULTRY COMMISSION #1 Natural Resources Drive Little Rock, Arkansas 72205 (501) 225-1598 REPORT ON FLEA MARKETS OR SALES CHECKED Poultry to be tested for pullorum typhoid are: exotic chickens, upland birds (chickens, pheasants, pea fowl, and backyard chickens). Must be identified with a leg band, wing band, or tattoo. Exemptions are those from a certified free NPIP flock or 90-day certificate test for pullorum typhoid. Water fowl need not test for pullorum typhoid unless they originate from out of state. -

Appendix APPENDIX TABLE 1

Appendix APPENDIX TABLE 1. ADDITIVES AND OTHER FOOD CHEMICALS-PRINCIPAL CHARACTERISTICS (See list of synonyms and other explanatory notes at end of table) Common Names (Other names) ~ Usual Sources Solubility and Function(s) Formula General Characteristics ~ ~ Acacia (gum arabic) Dried, gummy exudation. Acacia senegal (L.) Willd, and Water (freely soluble). t= Em ulsifier, stabilizer, other species in the Leguminosae Alcohol (insoluble). thickener. (Also see entry on family. V)~ Gums and Mucilages.) Acetaldehyde (ethanol) CH3CHO Colorless liquid with characteristic (1) Oxidation of ethanol or Water, alcohol, and organic solvents Flavoring agent odor. Flammable. ethylene. (2) Dry distillation of (miscible) . calcium acetate with calcium formate. Acetanisole (p-Methoxy C9H100 2 Pale yellow solid with Hawthorn Synthesis. Most fixed oils and propylene acetophenone like odor. glycol (soluble). Glycerin and Flavoring agent mineral oil (insoluble). Acetic Acid, Glacial CH3COOH Clear, colorless liquid with pungent, (1) Oxidation-fermentation of Water, alcohol, and glycerine Acidifier, Flavoring agent acrid odor. Acid taste when diluted. ethanol. (2) Oxidation of acetalde (miscible). hyde. (3) Direct synthesis from methanol and carbon monoxide. Acetoin (Acetyl methyl carbinol; CH3CH(OH)COCH3 Colorless, pale liquid (monomer). Fermentation of diacetyl. Water and propylene glycol Dimethylketol; 2-Hydroxy-2- White crystalline powder (dimer). (miscible). Vegetable oils butanone) Monomer has a characteristic (practically insoluble). Flavoring agent buttery odor. Acetone (2-Propanone; Dimethyl CH3COCH3 Clear, colorless liquid. Very volatile (1) Direct oxidation of propylene Water, alcohol, ether, chloroform ketone) with characteristic odor. Highly with air. (2) Fermentation of and most vegetable oils (miscible). Extraction solvent flammable. starch (also produces butanol). (3) Oxidation of cumene to form cumene hydroperoxide which de composes into acetone and phenol. -

Open Poultry

OPEN POULTRY Entry Fees: $2.75 Single Bird DEPARTMENT 803 ENTRIES CLOSE (Postmarked): ................................................................................ Monday, August 2nd Receive Open Poultry ...................................................... Saturday, August 28th – 8:00 a.m. – 8:00 p.m. All Open Poultry Must be Checked In ............................................... Saturday, August 28th @ 8:00 a.m. Open Poultry Show Judging ................................................................ Sunday, August 29th @ 9:00 a.m. Open Poultry Awards Presentation ..................................................... Sunday, August 29th @ 5:00 p.m. Begin Release of Non-Sale Open Poultry ........................................... Sunday, August 29th @ 6:30 p.m. ALL Poultry Must be Out ...................................................................... Sunday, August 29th @ 9:00 p.m. COMPETITION REQUIREMENTS: • All entrants must have read and be familiar with the Colorado State Fair General Competition Requirements, General Livestock Competition Requirements, and Health requirements. American Poultry Assn. show rules and Standard of Perfection breed standards shall apply. Submission of entries indicates acceptance of all show Competition Requirements and regulations. • All entrants for poultry exhibited in open, breed or market competitions shall provide a Premises Identification Number on the entry form. Entries not containing a Premises ID or NPIP will be returned to exhibitor. Incomplete entries will be returned to exhibitors, exhibitors will have 5 days within which to correct and return the entry or entry considered a completed entry and birds will not be allowed on grounds and will not be eligible for judging. • Entries must be postmarked on or before August 2nd. Entry fee via check or money order should accompany entry or entry should include a phone number in order to obtain a valid Credit Card. When cooping capacity is reached entries will be returned. -

Pyncheon Bantams

Volume 5, Number 1 Backyard February/March, 2010 PoultryDedicated to more and better small-flock poultry There’s Nothing Quite Like a Muscovy! Pg. 40 How to Photograph Your Flock Pg. 20 The Laying of an Egg An Amazing Process Pg.60 Plus: ...and more inside! 2 Backyard Poultry RANDALL BURKEY COMPANY Quality Animal Health Products since 1947 Live Baby Chicks Poultry Supplies Customer Services White Egg Layers Incubators & Brooders Free Catalog Brown Egg Layers Coops & Pens Friendly Operators Rare & Unique Breeds Nesting Boxes Web Shipping Special Bantams Medications One Year Warranty Turkeys & Waterfowl Feeders & Waterers Same Day Shipping* Guineas Egg Cartons *On in stock items ordered by 1pm CST Peafowl Books, CDs, & DVDs Toys & Treats Order by Phone 800-531-1097 Order Online randallburkey.com EverythingFebruary/March, 2010 you could want or needwww.backyardpoultrymag.com for poultry! 3 BACKYARD POULTRY Backyard 145 Industrial Dr. Medford, WI 54451 www.backyardpoultrymag.com 800-551-5691 Poultry Publisher: Dave Belanger Volume 5, Number 1 Editor: Elaine Belanger February/March, 2010 Managing Editor: Anne-marie Ida Editorial Assistant: Samantha Ingersoll Health: Circulation and Fulfillment: Laura From the Editor: Ching, Ellen Waichulis, Kate Tucker, Forget TV: Read Books to the The Answer Man .......................50 Chickens .......................................6 Kelly Weiler, Christine Barkley, The Laying of an Egg: An Gwendolyn Jones Bookstore: Ann Tom Reader’s Letters ......................8 Amazing Process ......................... -

2020 PRICE LIST Prices Are Subject to Change Without Notice and Do Not Include Shipping and Handling Charges

Email: [email protected] Phone: (814) 495-8057 or (814) 539-7026 Fax: (814) 495-8174 www.myerspoultry.com NPIP 23-524 2020 PRICE LIST Prices are subject to change without notice and do not include shipping and handling charges. We offer a variety of breeds to choose from while trying to keep prices reasonable. If a breed you’re interested in purchasing is not listed, call for availability and prices. HEAVY WHITE CORNISH CROSS BROILER S EX 1-10 11-24 25-49 50-99 100-299 300+ St. Run 2.55 2.25 1.91 1.62 1.42 call for Females 2.55 2.30 2.05 1.60 1.35 pricing Males 2.65 2.45 2.10 1.80 1.70 Coccidiosis Vaccine: .20 per chick only offering this option with the Heavy White Cornish Cross chicks when shipping by themselves. High Yield Broad Breasted Cornish Cross breed that makes great fryers (broilers) and roasters because of the weights that can be achieved. This breed has an excellent feed conversion, livability, strong legs, and a maximum white meat yield with a plump full confirmation. At 6 to 8 weeks of age processed weights of 4 ½ to 6 lbs. can be obtained. Higher weights can be obtained depending on the final grow out duration. With using a well-managed care and feeding program, customers have achieved processed weights of 10 to 14 lb. roasters and capons within 10 to 14 weeks. This breed Wrapped Heavy Cornish is also use for Cornish-Poussins (French for young chicken) 28 to 31 days will yield a Processed 5.25 lbs. -

The Chicken Encyclopedia the Chicken Encyclopedia

THE CHICKEN ENCYCLOPEDIA THE CHICKEN ENCYCLOPEDIA AN ILLUSTRATED REFERENCE GAIL DAMEROW author of Storey's Guide to Raising Chickens i Storey Publishing The mission ofStorey Publishing is to serve our customers by publishing practical information that encourages personal independence in halwony with the environment. Edited by Deborah Burns Art direction and book design by Alethea Morrison Text production by Sourena Parham Cover and interior illustrations by © Bethany Caskey, except as noted on page 319 Interior photography credits appear on page 319 Indexed by Samantha Miller © 2012 by Gail Damerow All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced without written permission from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote brief passages or reproduce illustrations in a review with appropriate credits; nor may any part of this book be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means - electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or other - without written permission from the publisher. The information in this book is true and complete to the best of our knowledge. All recommendations are made without guarantee on the part of the author or Storey Publishing. The author and publisher disclaim any liability in connection with the use of this information. Storey books are available for special premium and promotional uses and for customized editions. For further information, please call 1-800-793-9396. Storey Publishing 210 MASS MoCA Way North Adams. MA 01247 W�tw.storey.com Printed in the United States by Versa Press 10 987654321 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Damerow, Gail. -

Review on Productive and Reproductive Performance of Exotic Chicken Breed in Ethiopia

Vol. 8(3), pp. 244-251, April 2020 DOI: 10.14662/ARJASR2020.006 Academic Research Copy©right 2020 Author(s) retain the copyright of this article Journal of Agricultural ISSN: 2360-7874 http://www.academicresearchjournals.org/ARJASR/Index.htm Science and Research Research article Review on Productive and Reproductive Performance of Exotic Chicken Breed in Ethiopia Ararsa Bogale* and Chala Edae* * Ethiopian Institute of Agricultural Research Accepted 30 April 2020 According to many authors, there is a low productivity of local chicken breed and increment of demand of poultry, poultry product and by product in Ethiopia. To improve this problem, there are research activities on the breeding and nutritional improvement in the poultry sub sector of the livestock development. In case of breeding improvement, efforts are currently being made to alleviate this problem by introducing, evaluating, and identifying suitable high-performing exotic breeds that can adapt and to intensive and extensive management conditions in Ethiopia (Esatu et al., 2015; Ibrahim et al., 2018). Since 1950, there are a lot of exotic chicken imported in our country i.e layers, broilers and dual purpose chicken breeds. According to the findings of different research study, high egg and meat production can be obtained from different layers, dual purpose and broiler of exotic chicken breed in different agroecology of the Ethiopia. In addition to this, there are a lot of finding of reproductive performance parameters evaluation of exotic chicken(hatchability, average age of first mating of cockerels, average age at first egg and body weight and average number of cluthes per year per hen) by different authors in Ethiopia. -

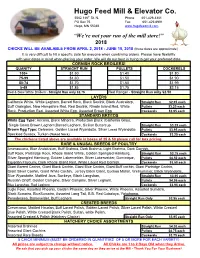

Hugo Feed Mill & Elevator

Hugo Feed Mill & Elevator Co. 5582 146th St. N. Phone 651-429-3361 PO Box 75 Fax 651-429-6991 Hugo, MN 55038 www.hugofeedmill.com “We’re not your run of the mill store!” 2018 CHICKS WILL BE AVAILABLE FROM APRIL 2, 2018 - JUNE 15, 2018 (these dates are approximate) It is very difficult to hit a specific date for eveyone when combining orders. Please have flexibility with your dates in mind when placing your order. We will do our best in trying to get your preferred date. CORNISH ROCK BROILERS! QUANITY STRAIGHT RUN PULLETS COCKERELS 100+ $1.50 $1.40 $1.80 75-99 $1.60 $1.50 $1.90 50-74 $1.70 $1.60 $1.99 5-49 $1.85 $1.75 $2.15 Red & Slow White Broilers - Straight Run only $2.75 Red Ranger - Straight Run only $2.50 LAYERS California White, White Leghorn, Barred Rock, Black Sexlink, Black Australorp, Straight Run $2.95 each Buff Orpington, New Hampshire Red, Red Sexlink, Rhode Island Red, White Pullets $3.25 each Rock, Production Red, Assorted White Egg, Assorted Brown Egg Cockerels $2.95 each STANDARD BREEDS White Egg Type: Ancona, Black Minorca, Production Black (California Gray), Single Comb Brown Leghorn,Barred Leghorn, Sicilian Buttercup. Straight Run $3.25 each Brown Egg Type: Deleware, Golden Laced Wyandotte, Silver Laced Wyandotte, Pullets $3.95 each Speckled Sussex, Turken (Naked Neck) Cockerels $3.25 each The chickens listed above are available in boxes of 25 & 50 please call for box pricing. RARE & UNUSAL BREEDS OF POULTRY Ameraucana, Blue Andalusian, Buff Brahma, Dark Brahma, Light Brahma, Dark Cornish, Buff Rock, Partiridge Rock, Rhode Island White, Golden Spangled Hamburg, Straight Run $3.75 each Silver Spangled Hamburg, Golden Lakenvelder, Silver Lakenvelder, Dominique, Pullets $4.50 each Egyptian Fayoumi, Dark Rhode Island Red, White Laced Red Cornish.