Christopher Isherwood's Seductive Berlin

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Christopher Isherwood Papers

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c8pk0gr7 No online items Christopher Isherwood Papers Finding aid prepared by Sara S. Hodson with April Cunningham, Alison Dinicola, Gayle M. Richardson, Natalie Russell, Rebecca Tuttle, and Diann Benti. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens Manuscripts Department The Huntington Library 1151 Oxford Road San Marino, California 91108 Phone: (626) 405-2191 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.huntington.org © October 2, 2000. Updated: January 12, 2007, April 14, 2010 and March 10, 2017 The Huntington Library. All rights reserved. Christopher Isherwood Papers CI 1-4758; FAC 1346-1397 1 Overview of the Collection Title: Christopher Isherwood Papers Dates (inclusive): 1864-2004 Bulk dates: 1925-1986 Collection Number: CI 1-4758; FAC 1346-1397 Creator: Isherwood, Christopher, 1904-1986. Extent: 6,261 pieces, plus ephemera. Repository: The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens. Manuscripts Department 1151 Oxford Road San Marino, California 91108 Phone: (626) 405-2191 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.huntington.org Abstract: This collection contains the papers of British-American writer Christopher Isherwood (1904-1986), chiefly dating from the 1920s to the 1980s. Consisting of scripts, literary manuscripts, correspondence, diaries, photographs, ephemera, audiovisual material, and Isherwood’s library, the archive is an exceptionally rich resource for research on Isherwood, as well as W.H. Auden, Stephen Spender and others. Subjects documented in the collection include homosexuality and gay rights, pacifism, and Vedanta. Language: English. Access The collection is open to qualified researchers by prior application through the Reader Services Department, with two exceptions: • The series of Isherwood’s daily diaries, which are closed until January 1, 2030. -

CABARET and ANTIFASCIST AESTHETICS Steven Belletto

CABARET AND ANTIFASCIST AESTHETICS Steven Belletto When Bob Fosse’s Cabaret debuted in 1972, critics and casual viewers alike noted that it was far from a conventional fi lm musical. “After ‘Cabaret,’ ” wrote Pauline Kael in the New Yorker , “it should be a while before per- formers once again climb hills singing or a chorus breaks into song on a hayride.” 1 One of the fi lm’s most striking features is indeed that all the music is diegetic—no one sings while taking a stroll in the rain, no one soliloquizes in rhyme. The musical numbers take place on stage in the Kit Kat Klub, which is itself located in a specifi c time and place (Berlin, 1931).2 Ambient music comes from phonographs or radios; and, in one important instance, a Hitler Youth stirs a beer-garden crowd with a propagandistic song. This directorial choice thus draws attention to the musical numbers as musical numbers in a way absent from conventional fi lm musicals, which depend on the audience’s willingness to overlook, say, why a gang mem- ber would sing his way through a street fi ght. 3 In Cabaret , by contrast, the songs announce themselves as aesthetic entities removed from—yet expli- cable by—daily life. As such, they demand attention as aesthetic objects. These musical numbers are not only commentaries on the lives of the var- ious characters, but also have a signifi cant relationship to the fi lm’s other abiding interest: the rise of fascism in the waning years of the Weimar Republic. -

Goodbye to Berlin: Erich Kästner and Christopher Isherwood

Journal of the Australasian Universities Language and Literature Association ISSN: 0001-2793 (Print) (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/yjli19 GOODBYE TO BERLIN: ERICH KÄSTNER AND CHRISTOPHER ISHERWOOD YVONNE HOLBECHE To cite this article: YVONNE HOLBECHE (2000) GOODBYE TO BERLIN: ERICH KÄSTNER AND CHRISTOPHER ISHERWOOD, Journal of the Australasian Universities Language and Literature Association, 94:1, 35-54, DOI: 10.1179/aulla.2000.94.1.004 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1179/aulla.2000.94.1.004 Published online: 31 Mar 2014. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 33 Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=yjli20 GOODBYE TO BERLIN: ERICH KASTNER AND CHRISTOPHER ISHERWOOD YVONNE HOLBECHE University of Sydney In their novels Fabian (1931) and Goodbye to Berlin (1939), two writers from different European cultures, Erich Mstner and Christopher Isherwood, present fictional models of the Berlin of the final years of the Weimar Republic and, in Isherwood's case, the beginning of the Nazi era as wel1. 1 The insider Kastner—the Dresden-born, left-liberal intellectual who, before the publication ofFabian, had made his name as the author not only of a highly successful children's novel but also of acute satiric verse—had a keen insight into the symptoms of the collapse of the republic. The Englishman Isherwood, on the other hand, who had come to Berlin in 1929 principally because of the sexual freedom it offered him as a homosexual, remained an outsider in Germany,2 despite living in Berlin for over three years and enjoying a wide range of contacts with various social groups.' At first sight the authorial positions could hardly be more different. -

44-Christopher Isherwood's a Single

548 / RumeliDE Journal of Language and Literature Studies 2020.S8 (November) Christopher Isherwood’s A Single Man: A work of art produced in the afternoon of an author’s life / G. Güçlü (pp. 548-562) 44-Christopher Isherwood’s A Single Man: A work of art produced in the afternoon of an author’s life Gökben GÜÇLÜ1 APA: Güçlü, G. (2020). Christopher Isherwood’s A Single Man: A work of art produced in the afternoon of an author’s life. RumeliDE Dil ve Edebiyat Araştırmaları Dergisi, (Ö8), 548-562. DOI: 10.29000/rumelide.816962. Abstract Beginning his early literary career as an author who nurtured his fiction with personal facts and experiences, many of Christopher Isherwood’s novels focus on constructing an identity and discovering himself not only as an adult but also as an author. He is one of those unique authors whose gradual transformation from late adolescence to young and middle adulthood can be clearly observed since he portrays different stages of his life in fiction. His critically acclaimed novel A Single Man, which reflects “the afternoon of his life;” is a poetic portrayal of Isherwood’s confrontation with ageing and death anxiety. Written during the early 1960s, stormy relationship with his partner Don Bachardy, the fight against cancer of two of his close friends’ (Charles Laughton and Aldous Huxley) and his own health problems surely contributed the formation of A Single Man. The purpose of this study is to unveil how Isherwood’s midlife crisis nurtured his creativity in producing this work of fiction. From a theoretical point of view, this paper, draws from literary gerontology and ‘the Lifecourse Perspective’ which is a theoretical framework in social gerontology. -

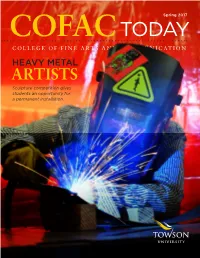

COFAC Today Spring 2017

Spring 2017 COFAC TODAY COLLEGE OF FINE ARTS AND COMMUNICATION HEAVY METAL ARTISTS Sculpture competition gives students an opportunity for a permanent installation. COFAC TODAY COLLEGE OF FINE ARTS AND COMMUNICATION DEAN, COLLEGE OF DEAR FRIENDS, FAMILIES, AND COLLEAGUES, FINE ARTS & COMMUNICATION Susan Picinich The close of an academic year brings with it a sense of pride and anticipation. The College of Fine Arts and Communication bustles with excitement as students finish final projects, presentations, exhibitions, EDITOR Sedonia Martin concerts, recitals and performances. Sr. Communications Manager In this issue of COFAC Today we look at the advancing professional career of dance alum Will B. Bell University Marketing and Communications ’11 who is making his way in the world of dance including playing “Duane” in the live broadcast of ASSOCIATE EDITOR Hairspray Live, NBC television’s extravaganza. Marissa Berk-Smith Communications and Outreach Coordinator The Asian Arts & Culture Center (AA&CC) presented Karaoke: Asia’s Global Sensation, an exhibition College of Fine Arts and Communication that explored the world-wide phenomenon of karaoke. Conceived by AA&CC director Joanna Pecore, WRITER students, faculty and staff had the opportunity to belt out a song in the AA&CC gallery while learning Wanda Haskel the history of karaoke. University Marketing and Communications DESIGNER Music major Noah Pierre ’19 and Melanie Brown ’17 share a jazz bond. Both have been playing music Rick Pallansch since childhood and chose TU’s Department of Music Jazz Studies program. Citing outstanding faculty University Marketing and Communications and musical instruction, these students are honing their passion of making music and sharing it with PHOTOGRAPHY the world. -

Daniel Curzon Papers, 1950S-2014GLC 52

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c8pv6phm No online items Daniel Curzon Papers, 1950s-2014GLC 52 Finding aid prepared by Tim Wilson James C. Hormel Gay & Lesbian Center, San Francisco Public Library 100 Larkin Street San Francisco, CA, 94102 (415) 557-4400 [email protected] 2015 Daniel Curzon Papers, GLC 52 1 1950s-2014GLC 52 Title: Daniel Curzon Papers, Date (inclusive): 1950s-2014 Collection Identifier: GLC 52 Creator: Curzon, Daniel Physical Description: 87.0 boxes + oversized material in flat files Contributing Institution: James C. Hormel Gay & Lesbian Center, San Francisco Public Library 100 Larkin Street San Francisco, CA, 94102 (415) 557-4400 [email protected] Abstract: Daniel Curzon (pseudonym of Daniel Brown) is a novelist, playwright and educator. His novels include Something You Do in the Dark, From Violent Men, and The World Can Break Your Heart. The Curzon Papers contain draft manuscripts for books, plays, songs, and articles by Curzon; personal and professional correspondence; mailing lists and clippings related to the management of IGNA (International Gay News Agency); clippings and reviews regarding Curzon's work; audiovisual materials; correspondence and legal materials related to a case against City College of San Francisco and the Teacher Review website; and photographs. Physical Location: The collection is stored onsite. Languages represented: Collection materials are in English. Access The collection is available for use during San Francisco History Center hours, with photographs available during Photo Desk hours. Collections that are stored offsite should be requested 48 hours in advance. Publication Rights Copyright and literary rights for Curzon's published and unpublished works are retained by Daniel Curzon. -

CABARET SYNOPSIS the Scene Is a Sleazy Nightclub in Berlin As The

CABARET SYNOPSIS The scene is a sleazy nightclub in Berlin as the 1920s are drawing to a close. Cliff Bradshaw, a young American writer, and Ernst Ludwig, a German, strike up a friendship on a train. Ernst gives Cliff an address in Berlin where he will find a room. Cliff takes this advice and Fräulein Schneider, a vivacious 60 year old, lets him have a room very cheaply. Cliff, at the Kit Kat Club, meets an English girl, Sally Bowles, who is working there as a singer and hostess. Next day, as Cliff is giving Ernst an English lesson, Sally arrives with all her luggage and moves in. Ernst comes to ask Cliff to collect something for him from Paris; he will pay well for the service. Cliff knows that this will involve smuggling currency, but agrees to go. Ernst's fee will be useful now that Cliff and Sally are to be married. Fraulein Schneider and her admirer, a Jewish greengrocer named Herr Schultz, also decide to become engaged and a celebration party is held in Herr Schultz shop. In the middle of the festivities Ernst arrives wearing a Nazi armband. Cliff realizes that his Paris errand was on behalf of the Nazi party and refuses Ernst's payment, but Sally accepts it. At Cliff's flat Sally gets ready to go back to work at the Kit Kat Klub. Cliff determines that they will leave for America but that evening he calls at the Klub and finds Sally there. He is furious, and when Ernst approaches him to perform another errand Cliff knocks him down. -

European Political Cultures, Part 3. Goodbye to Berlin In

European Studies: European political cultures, part 3. Goodbye to Berlin In this paper I am going to write a critical and reflective essay about the novel “Goodbye to Berlin”. For the analysis chapter I use the studied concepts, theories and the historical context. My work in this essay start with a short introduction on the novel "Goodbye to Berlin" and then I will combine the novel with main characters, the time, movie and music. On the last chapter of this essay, I will write my own reflection and my own opinion about the novel. The best way to achieve correct information about this novel is that to read relevant materials like books, movies, web pages and articles which can give correct information. Short facts Title: Goodbye to Berlin Author: Christopher Isherwood Country: Great Britannia and Germany Genre: Diary novel Year of publication: 1939 Main characters: Christopher, Sally, Otto, Natalia and Bernhard. Music: Cabaret Movie: Isherwood and his kind /Written by Aria Rezai, student at Malmö University. European Studies: European political cultures, part 3. Introduction "Goodbye to Berlin" is a novel that is written by the British author Christopher William Bradshaw Isherwood. This novel takes place in Berlin between 1930 and 1933 and was published in English on 1939, and in Swedish on 1954 by translating of Tage Svensson and by Leif Janzon on 2009. This novel contains six chapters and each chapter is a short story about Isherwood’s daily experiences. The story starts from then he was travelling to Berlin until he left Berlin forever (Leijonhufvud 2009 and Montelius 2009). -

People, Objects, and Anxiety in Thirties British Fiction Emily O'keefe Loyola University Chicago

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Loyola eCommons Loyola University Chicago Loyola eCommons Dissertations Theses and Dissertations 2012 The Things That Remain: People, Objects, and Anxiety in Thirties British Fiction Emily O'Keefe Loyola University Chicago Recommended Citation O'Keefe, Emily, "The Things That Remain: People, Objects, and Anxiety in Thirties British Fiction" (2012). Dissertations. Paper 374. http://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_diss/374 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at Loyola eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Loyola eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 License. Copyright © 2012 Emily O'keefe LOYOLA UNIVERSITY CHICAGO THE THINGS THAT REMAIN: PEOPLE, OBJECTS, AND ANXIETY IN THIRTIES BRITISH FICTION A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE GRADUATE SCHOOL IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY PROGRAM IN ENGLISH BY EMILY O‘KEEFE CHICAGO, ILLINOIS AUGUST 2012 Copyright by Emily O‘Keefe, 2012 All rights reserved. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Thank you to Joyce Wexler, who initially inspired me to look beyond symbolism to find new ways of engaging with material things in texts. Her perceptive readings of several versions of these chapters guided and encouraged me. To Pamela Caughie, who urged me to consider new and fascinating questions about theory and periodization along the way, and who was always ready to offer practical guidance. To David Chinitz, whose thorough and detailed comments helped me to find just the right words to frame my argument. -

Claude Summers Reflects on Chris and Don

Special Features Index Claude Summers Reflects on Chris and Don Newsletter February 1, 2009 Sign up for glbtq's Portrait of a Marriage, Portrait of an Artist: free newsletter to Chris and Don: A Love Story receive a spotlight on GLBT culture by Claude J. Summers every month. e-mail address In Christopher Isherwood's 1976 sexual and political autobiography, Christopher and His Kind, 1929-1939, the novelist reassesses the decade in subscribe which he earned fame as one of the young writers of the 1930s. He begins privacy policy unsubscribe by announcing that "To Christopher, Berlin meant Boys." He ends it, however, with the event in his life that Encyclopedia proved even more decisive than his visit to Berlin: his 1939 emigration to the Discussion go Don Bachardy painting United States with his friend poet W. Christopher Isherwood in H. Auden. the early 1980s. Photograph by Jack Shear, In the book's remarkable final courtesy Zeitgeist Films. paragraph, Isherwood looks back on the two young men as they are about to begin new lives in America and answers one final question: "Yes, my dears, each of you will find the person you came here to look for--the ideal companion to whom you can reveal yourself totally and yet be loved for what you are, not what you pretend to be." Log In Now For Auden, that ideal companion was Chester Kallman, whom he met within three months of his arrival in America and with whom he Forgot Your Password? spent most of the rest of his life. Not a Member Yet? JOIN TODAY. -

Sankara's Doctrine of Maya Harry Oldmeadow

The Matheson Trust Sankara's Doctrine of Maya Harry Oldmeadow Published in Asian Philosophy (Nottingham) 2:2, 1992 Abstract Like all monisms Vedanta posits a distinction between the relatively and the absolutely Real, and a theory of illusion to explain their paradoxical relationship. Sankara's resolution of the problem emerges from his discourse on the nature of maya which mediates the relationship of the world of empirical, manifold phenomena and the one Reality of Brahman. Their apparent separation is an illusory fissure deriving from ignorance and maintained by 'superimposition'. Maya, enigmatic from the relative viewpoint, is not inexplicable but only not self-explanatory. Sankara's exposition is in harmony with sapiential doctrines from other religious traditions and implies a profound spiritual therapy. * Maya is most strange. Her nature is inexplicable. (Sankara)i Brahman is real; the world is an illusory appearance; the so-called soul is Brahman itself, and no other. (Sankara)ii I The doctrine of maya occupies a pivotal position in Sankara's metaphysics. Before focusing on this doctrine it will perhaps be helpful to make clear Sankara's purposes in elaborating the Advaita Vedanta. Some of the misconceptions which have afflicted English commentaries on Sankara will thus be banished before they can cause any further mischief. Firstly, Sankara should not be understood or approached as a 'philosopher' in the modern Western sense. Ananda Coomaraswamy has rightly insisted that, The Vedanta is not a philosophy in the current sense of the word, but only as it is used in the phrase Philosophia Perennis... Modern philosophies are closed systems, employing the method of dialectics, and taking for granted that opposites are mutually exclusive. -

Christopher Isherwood in Transit: a 21St-Century Perspective

Transcription University of Minnesota Press Episode 2: Christopher Isherwood in Transit: A 21st-Century Perspective https://soundcloud.com/user-760891605/isherwood-in-transit Host introduction: Isherwood in Transit is a collection of essays that considers Christopher Isherwood as a transnational writer whose identity politics and beliefs were constantly transformed by global connections arising from journeys to Germany, Japan, China and Argentina; his migration to the United States; and his conversion to Vedanta Hinduism in the 1940s. We're here today to talk about Isherwood's reception and history of publication in the US, as well as what we mean by the title Isherwood in Transit, which is open to interpretation and refers to the writer's movement on a personal and spiritual level as much as geographic. Here we have book editors Jim Berg and Chris Freeman, who have co-edited several volumes on Isherwood, including The Isherwood Century and The American Isherwood. Berg is associate dean of faculty at the Borough of Manhattan Community College in New York City. Freeman is professor of English and gender studies at the University of Southern California. They are joined by University of Minnesota press director Doug Armato. This conversation was recorded in June 2020. Jim Berg: This is Jim Berg. Here's a quick bit of background on Christopher Isherwood. He was born in 1904 in England. His best-known British work is Goodbye to Berlin from 1938, which was published with Mr. Norris Changes Trains in the United States as The Berlin Stories featuring Sally Bowles. And that was turned into the musical Cabaret.