Feminist and Queer Science Fiction in America

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1970S Feminist Science Fiction As Radical Rhetorical Revisioning. (2014) Directed by Dr

BELK, PATRICK NOLAN, Ph.D. Let's Just Steal the Rockets: 1970s Feminist Science Fiction as Radical Rhetorical Revisioning. (2014) Directed by Dr. Hephzibah Roskelly. 204 pages. Feminist utopian writings from the 1970s included a clearly defined rhetorical purpose: to undermine the assumption of hidden male privilege in language and society. The creative conversation defining this rhetorical purpose gives evidence of a community of peers engaging in invention as a social act even while publishing separately. Writers including Samuel Delany, Joanna Russ, James Tiptree, Jr., and Ursula Le Guin were writing science fiction as well as communicating regularly with one another during the same moments that they were becoming fully conscious of the need to express the experiences of women (and others) in American literary and academic society. These creative artists formed a group of loosely affiliated peers who had evolved to the same basic conclusion concerning the need for a literature and theory that could finally address the science of social justice. Their literary productions have been well-studied as contemporaneous feminist utopias since Russ’s 1981 essay “Recent Feminist Utopias.” However, much can be understood about their rhetorical process of spreading the meme of feminist equality once we go beyond the literary productions and more closely examine their letters, essays, and commentary. This dissertation will show that this group of utopian fiction writers can be studied as exactly that: a loosely connected, collaborative, creative group of peers with specific ideas about how humanity could be better if assumptions of male superiority were undermined and with the rhetorical means to spread those ideas in ways which changed the literary and social conversation. -

(Minneapolis). Dog

♦♦SPECIAL "A Whole Shiny New Year to Mess Up" January 1994 Issue of EINBLATT^ DEC 31 (Fri): Minn-STF New Year's Eve Party. 7 pm until early 1994, at home of Susan Ryan / 2958 Sheridan Ave. N. (Minneapolis). Dog. Smoking permitted. "Somewhat childproof— kids welcome." FFI: 529-9480. 31 (Fri): Flash Girls and Cats Laughing, among others, play New Year's gig at the Irish Well (University and Prior in St. Paul). $6 admission. Gallowglass at 8:00; Flash Girls at 9:05; Cats Laughing at 10:15; Bedlam Boys at 11:30. 31 (Fri): Conadian (Winnipeg Worldcon) attending rates goes up tomorrow (today, $95). JAN 1 (Sat): SHOCKWAVE, with DavE Romm, moves to a new time today: 6 to 6:30 Saturdays, still on KFAI-FM (90.3). It's followed at 6:30 pm by debut of a new show, SOUND AFFECTS, hosted by Jerry Stearns. TOM SWIFT AND HIS FANNISH RADIO-ACTIVITY, anyone? 8 (Sat): Minn-STF Meeting. 1:30 pm on, at home of Bill Bader and Ann Totusek / 2726 Knox Ave. N. (Mpls). FFI: 522-0545. 8 (Sat): Minneapa 297 collation. 2 pm, at the Meeting. Copy count 30. FFI: 827-1775. 10 (Mon): Diversicon II attending rates go up tomorrow from $20 to $25. 11 (Tue): Diversicon meeting. 7 pm, at home of Greg Johnson / 1801 Elliot Ave. S.— #11 (Mpls). Topic: Programming. FFI: Greg at 872-6926 or Eric at 825-9353. 14 (Fri): North Country Gaylaxians meeting. 7 pm, at 4141 11th Ave. S. FFI: 870-0168. 15 (Sat): World Building Society meets at 1 pm at Boomer's Saloon and Deli / 312 Central Ave. -

The Imagined Wests of Kim Stanley Robinson in the "Three Californias" and Mars Trilogies

Portland State University PDXScholar Urban Studies and Planning Faculty Nohad A. Toulan School of Urban Studies and Publications and Presentations Planning Spring 2003 Falling into History: The Imagined Wests of Kim Stanley Robinson in the "Three Californias" and Mars Trilogies Carl Abbott Portland State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/usp_fac Part of the Urban Studies and Planning Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Citation Details Abbott, C. Falling into History: The Imagined Wests of Kim Stanley Robinson in the "Three Californias" and Mars Trilogies. The Western Historical Quarterly , Vol. 34, No. 1 (Spring, 2003), pp. 27-47. This Article is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Urban Studies and Planning Faculty Publications and Presentations by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. Falling into History: The ImaginedWests of Kim Stanley Robinson in the "Three Californias" and Mars Trilogies Carl Abbott California science fiction writer Kim Stanley Robinson has imagined the future of Southern California in three novels published 1984-1990, and the settle ment of Mars in another trilogy published 1993-1996. In framing these narratives he worked in explicitly historical terms and incorporated themes and issues that characterize the "new western history" of the 1980s and 1990s, thus providing evidence of the resonance of that new historiography. .EDMars is Kim Stanley Robinson's R highly praised science fiction novel published in 1993.1 Its pivotal section carries the title "Falling into History." More than two decades have passed since permanent human settlers arrived on the red planet in 2027, and the growing Martian communities have become too complex to be guided by simple earth-made plans or single individuals. -

Readercon 14

readercon 14 program guide The conference on imaginative literature, fourteenth edition readercon 14 The Boston Marriott Burlington Burlington, Massachusetts 12th-14th July 2002 Guests of Honor: Octavia E. Butler Gwyneth Jones Memorial GoH: John Brunner program guide Practical Information......................................................................................... 1 Readercon 14 Committee................................................................................... 2 Hotel Map.......................................................................................................... 4 Bookshop Dealers...............................................................................................5 Readercon 14 Guests..........................................................................................6 Readercon 14: The Program.............................................................................. 7 Friday..................................................................................................... 8 Saturday................................................................................................14 Sunday................................................................................................. 21 Readercon 15 Advertisement.......................................................................... 26 About the Program Participants......................................................................27 Program Grids...........................................Back Cover and Inside Back Cover Cover -

OLOC's Media Library (As of 1-25-2020) ***************************************************

OLOC’s Media Library (as of 1-25-2020) ************************************************************************************ About the Library: OLOC is proud of our fine and growing media collection, which is available for members and supporters to borrow. The Library is focused on Old Lesbians, although we do have a few selections that feature young Lesbians and/or old women who may or may not be or have been Lesbians, but the films are of interest to Old Lesbians. We also have a few that include men. All materials are on DVD or CD. Each time the list is updated, it will be posted on our website at https://oloc.org/media-library/. There will also be announcements in the OLOC Reporter, available in PDF by email and in print, and in the monthly OLOC E-News. How to Borrow Our Media: We request a donation of $5 or more per item to cover the costs of mailing. We also ask that you keep films for no longer than two weeks and order as far ahead as you can so that we can be sure to get them to you when you need them. Check with Susan Wiseheart, our administrator, for possible reduced rates if you want to borrow more than one at a time. To purchase movies, search the internet or a source such as Wolfe Video (owned and staffed by OLOC supporters), the feminist bookstores at https://oloc.org/feminist-bookstores/ (for special order if necessary), or the film’s website, if it has one. • For your own printable PDF, go to https://oloc.org/media-library/ and click on the link there. -

Mirrorshade Women: Feminism and Cyberpunk

Mirrorshade Women: Feminism and Cyberpunk at the Turn of the Twenty-first Century Carlen Lavigne McGill University, Montréal Department of Art History and Communication Studies February 2008 A thesis submitted to McGill University in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Communication Studies © Carlen Lavigne 2008 2 Abstract This study analyzes works of cyberpunk literature written between 1981 and 2005, and positions women’s cyberpunk as part of a larger cultural discussion of feminist issues. It traces the origins of the genre, reviews critical reactions, and subsequently outlines the ways in which women’s cyberpunk altered genre conventions in order to advance specifically feminist points of view. Novels are examined within their historical contexts; their content is compared to broader trends and controversies within contemporary feminism, and their themes are revealed to be visible reflections of feminist discourse at the end of the twentieth century. The study will ultimately make a case for the treatment of feminist cyberpunk as a unique vehicle for the examination of contemporary women’s issues, and for the analysis of feminist science fiction as a complex source of political ideas. Cette étude fait l’analyse d’ouvrages de littérature cyberpunk écrits entre 1981 et 2005, et situe la littérature féminine cyberpunk dans le contexte d’une discussion culturelle plus vaste des questions féministes. Elle établit les origines du genre, analyse les réactions culturelles et, par la suite, donne un aperçu des différentes manières dont la littérature féminine cyberpunk a transformé les usages du genre afin de promouvoir en particulier le point de vue féministe. -

1 Science Fiction As a Worldwide Phenomenon

PROCEEDINGS, COINs13 SCIENCE FICTION AS A WORLDWIDE PHENOMENON: A STUDY OF INTERNATIONAL CREATION, CONSUMPTION AND DISSEMINATION Elysia Celeste Wells Savannah College of Art and Design 342 Bull St Savannah, GA 31402 USA e-mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT Companion to Science Fiction almost exclusively This paper examines the international nature of focuses on American science fiction (James & science fiction. The focus of this research is to Mendlesohn, 2003). Julies Verne is one of the few determine whether science fiction is primarily non-English speaking authors to be named in many English speaking and Western or global; being of the books reviewed for this research. (Clarke, created and consumed by people in non-Western, 1999; James & Mendlesohn, 2003; Kelly et al., non-English speaking countries? Science fiction's 2009, p. 10). Does this mean that science fiction is international presence was found in three ways, by a genre that is found primarily in the English network analysis, by examining a online retailer speaking West2 or are there science fiction stories and with a survey. Condor, a program developed being written all around the world that simply have by GalaxyAdvisors was used to determine if not been addressed by the reviewed literature? science fiction is being talked about by non-English speakers. An analysis of the international Amazon.com websites was done to discover if it Literature Review was being consumed worldwide. A survey was In an essay written by James Gunn for World also conducted to see if people had experience with Literature Today he states that "American science science fiction. -

Table of Contents MAIN STORIES American Science Fiction, 1960-1990, Ursula K

Table of Contents MAIN STORIES American Science Fiction, 1960-1990, Ursula K. ConFrancisco Report........................................... 5 Le Guin & Brian Attebery, eds.; Chimera, Mary 1993 Hugo Awards W inners................................5 Rosenblum; Core, Paul Preuss; A Tupolev Too Nebula Awards Weekend 1994 ............................6 Far, Brian Aldiss; SHORT TAKES: Argyll: A The Preiss/Bester Connection.............................6 Memoir, Theodore Sturgeon; The Rediscovery THE NEWSPAPER OF THE SCIENCE FICTION FIELD Delany Back in P rint............................................ 6 of Man: The Complete Short Science Fiction of HWA Changes......................................................6 Cordwainer Smith, Cordwainer Smith. (ISSN-0047-4959) 1992 Chesley Awards W inners............................6 Reviews by Russell Letson:................................21 EDITOR & PUBLISHER Bidding War for Paramount.................................7 The Mind Pool, Charles Sheffield; More Than Charles N. Brown Battle of the Fantasy Encyclopedias................... 7 Fire, Philip Jose Farmer; The Sea’s Furthest ASSOCIATE EDITOR Fantasy Shop Helps AIDS F u n d ......................... 9 End, Damien Broderick. SPECIAL FEATURES Reviews by Faren M iller................................... 23 Faren C. Miller Complete Hugo Voting.......................................36 Green Mars, Kim Stanley Robinson; Brother ASSISTANT EDITORS 1993 Hugo Awards Ceremony........................... 38 Termite, Patricia Anthony; Lasher, Anne Rice; A Marianne -

W41 PPB-Web.Pdf

The thrilling adventures of... 41 Pocket Program Book May 26-29, 2017 Concourse Hotel Madison Wisconsin #WC41 facebook.com/wisconwiscon.net @wisconsf3 Name/Room No: If you find a named pocket program book, please return it to the registration desk! New! Schedule & Hours Pamphlet—a smaller, condensed version of this Pocket Program Book. Large Print copies of this book are available at the Registration Desk. TheWisSched app is available on Android and iOS. What works for you? What doesn't? Take the post-con survey at wiscon.net/survey to let us know! Contents EVENTS Welcome to WisCon 41! ...........................................1 Art Show/Tiptree Auction Display .........................4 Tiptree Auction ..........................................................6 Dessert Salon ..............................................................7 SPACES Is This Your First WisCon?.......................................8 Workshop Sessions ....................................................8 Childcare .................................................................. 10 Children's and Teens' Programming ..................... 11 Children's Schedule ................................................ 11 Teens' Schedule ....................................................... 12 INFO Con Suite ................................................................. 12 Dealers’ Room .......................................................... 14 Gaming ..................................................................... 15 Quiet Rooms .......................................................... -

Science Fiction in Nanotechnology

Bridging the Gaps: Science Fiction in Nanotechnology José López Abstract: This paper argues that narrative elements from the science fiction (SF) literary genre are used in the discourse of Nanoscience and Technology (NST) to bridge the gap between what is technically possible today and its in- flated promises for the future. The argument is illustrated through a detailed discussion of two NST texts. The paper concludes by arguing that the use of SF narrative techniques poses serious problems to the development of a criti- cal analysis of the ethical and social implications of NST. Keywords : nanoscience and technology , ethical and social implications , science fiction , extrapolation . 1. Introduction 1 In 1997, Francis Collins, the spokesperson for the US Human Genome Pro- ject (HGP), claimed that, “the project’s Ethical, Legal and Social Implications (ELSI) program [was] unique among technology programs in its mandate to consider and deal with these issues alongside the development of the tech- nology” (cited in McCain 2003, p. 112). Recent assessments of its impact have been far from celebratory ( e.g. Evans 2002, Huijer 2003, McCain 2003). Indeed, it is claimed that the ELSI program insulated the HGP from criticism rather than facilitating negotiations between scientists and non-scientists (Huijer 2003, p. 488). Against this background, when Mihail Roco, a key promoter of nanosci- ence and technology (NST) 2 in the U.S. and director of the National Nano- technology Initiative (NNI), claims that societal implications have been an integral component of the NNI from the start and argues that the National Science Foundation (NSF) “has made support for social, ethical and econom- ic research studies a priority” (Roco 2003a, p. -

Balticon 47 Program Participants

BALTICON 47 52 THE BSFAN Balticon 47 Program Participants JoAnn W. Abbott A. L. Davroe Heidi Hooper Danielle Ackley-McPhail Susan de Guardiola Starla Huchton Lisa Adler-Golden Donna Dearborn Kara Hurvitz D. H. Aire (Barry Nove) James K. Decker Michele Hymowitz Leigh Alexander Ming Diaz Eric Hymowitz Tristan Alexander Tim Dodge Christopher Impink Day Al-Mohamed Tom Doyle Noam Izenberg Scott H. Andrews Valerie Durham Mark Jeffrey Ami Angelwings James Durham Leslie Johnston Catherine A. Asaro Collin Earl Paula S. Jordan John Ashmead Gaia Eirich Jason Kalirai Lisa Ashton Chris Evans Amy L. Kaplan Thomas G. Atkinson Eric “Dr. Gandalf ” Fleischer Bruce Kaplan Jason Banks Halla Fleischer Debra Kaplan Brick Barrientos Judi Fleming William H. Kennedy Martin Berman-Gorvine Doc Frankenfield Kira Deja Biernesser D. Douglas Fratz James R. Knapp Steve Biernesser Nancy C. Frey Jonah Knight Joshua Bilmes Clint Gaige Beatrice Kondo Danny Birt Allison Gamblin Yoji Kondo (Eric Kotani) Roxanne Bland Charles E. Gannon Brian Koscienski Art Blumberg Lia Garrott A B Kovacs Sue Bowen Dr. Pamela L. Gay Laura E. Kovalcin Walter H. Boyes, Jr. Marty Gear Theodore Krulik William T. (Tom) Bridgman Veronica (V.) Giguere Alessandro La Porta Alessia Brio Phil Giunta Mur Lafferty J. Sherlock III Brown Alicia Goranson Jagi Lamplighter KT Bryski James L. Gossard Grig “Punkie” Larson Stephanie Burke Stephen Granade Marcus Lawrence Laura Burns Matthew Granoff Dina Leacock Mildred G. Cady Bob Greenberger R. Allen Leider Jack Campbell Irina Greenman Neal Levin Renee Chambliss Damien Walters Grintalis Emily Lewis Christine Chase Sonya “Patches” Gross Carey Lisse Robert R. Chase Gay Haldeman ScienceTim Livengood Bryan Chevalier Joe Haldeman Andy Love Ariel Cinii Elektra Hammond Steve Lubs Carl Cipra Eric V. -

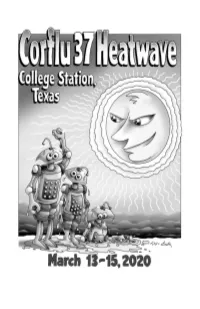

Corflu 37 Program Book (March 2020)

“We’re Having a Heatwave”+ Lyrics adapted from the original by John Purcell* We’re having a heatwave, A trufannish heatwave! The faneds are pubbing, The mimeo’s humming – It’s Corflu Heatwave! We’re starting a heatwave, Not going to Con-Cave; From Croydon to Vegas To bloody hell Texas, It’s Corflu Heatwave! —— + scansion approximate (*with apologies to Irving Berlin) 2 Table of Contents Welcome to Corflu 37! The annual Science Fiction Fanzine Fans’ Convention. The local Texas weather forecast…………………………………….4 Program…………………………………………………………………………..5 Local Restaurant Map & Guide…………..……………………………8 Tributes to Steve Stiles:…………………………………………………..12 Ted White, Richard Lynch, Michael Dobson Auction Catalog……………………………………………………………...21 The Membership…………………………………………………………….38 The Responsible Parties………………………………………………....40 Writer, Editor, Publisher, and producer of what you are holding: John Purcell 3744 Marielene Circle, College Station, TX 77845 USA Cover & interior art by Teddy Harvia and Brad Foster except Steve Stiles: Contents © 2020 by John A. Purcell. All rights revert to contrib- uting writers and artists upon publication. 3 Your Local Texas Weather Forecast In short, it’s usually unpredictable, but usually by mid- March the Brazos Valley region of Texas averages in dai- ly highs of 70˚ F, and nightly lows between 45˚to 55˚F. With that in mind, here is what is forecast for the week that envelopes Corflu Heatwave: Wednesday, March 11th - 78˚/60˚ F or 26˚/16˚C Thursday, March 12th - 75˚/ 61˚ F or 24˚/15˚ C Friday, March 13th - 77˚/ 58˚ F or 25 / 15˚ C - Saturday, March 14th - 76˚/ 58 ˚F or 24 / 15˚C Sunday, March 15th - 78˚ / 60˚ F or 26˚/16˚C Monday March 16th - 78˚ / 60˚ F or 26˚/ 16˚C Tuesday, March 17th - 78˚ / 60˚ F or 26˚/ 16˚C At present, no rain is in the forecast for that week.