The Influence of Rugby League In/On the Pacific

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Position Australia Cook Islands England Fullback Billy Slater

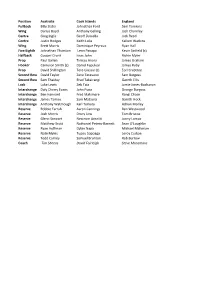

Position Australia Cook Islands England Fullback Billy Slater Johnathan Ford Sam Tomkins Wing Darius Boyd Anthony Gelling Josh Charnley Centre Greg Inglis Geoff Daniella Jack Reed Centre Justin Hodges Keith Lulia Kallum Watkins Wing Brett Morris Dominique Peyroux Ryan Hall Five Eighth Johnathan Thurston Leon Panapa Kevin Sinfield (c) Halfback Cooper Cronk Issac John Richie Myler Prop Paul Gallen Tinirau Arona James Graham Hooker Cameron Smith (c) Daniel Fepuleai James Roby Prop David Shillington Tere Glassie (c) Eorl Crabtree Second Row David Taylor Zane Tetevano Sam Burgess Second Row Sam Thaiday Brad Takairangi Gareth Ellis Lock Luke Lewis Zeb Taia Jamie Jones-Buchanan Interchange Daly Cherry Evans John Puna George Burgess Interchange Ben Hannant Fred Makimare Rangi Chase Interchange James Tamou Sam Mataora Gareth Hock Interchange Anthony Watmough Karl Temata Adrian Morley Reserve Robbie Farrah Aaron Cannings Ben Westwood Reserve Josh Morris Drury Low Tom Briscoe Reserve Glenn Stewart Neccrom Areaiiti Jonny Lomax Reserve Matthew Scott Nathaniel Peteru-Barnett Sean O'Loughlin Reserve Ryan Hoffman Dylan Napa Michael Mcllorum Reserve Nate Myles Tupou Sopoaga Leroy Cudjoe Reserve Todd Carney Samuel Brunton Rob Burrow Coach Tim Sheens David Fairleigh Steve Mcnamara Fiji France Ireland Italy Jarryd Hayne Tony Gigot Greg McNally James Tedesco Lote Tuqiri Cyril Stacul John O’Donnell Anthony Minichello (c) Daryl Millard Clement Soubeyras Stuart Littler Dom Brunetta Wes Naiqama (c) Mathias Pala Joshua Toole Christophe Calegari Sisa Waqa Vincent -

TO: NZRL Staff, Districts and Affiliates and Board FROM: Cushla Dawson

TO: NZRL Staff, Districts and Affiliates and Board FROM: Cushla Dawson DATE: 28 October 2008 RE: Media Summary Wednesday 29 October to Monday 03 November 2008 Slater takes place among the greats: AUSTRALIA 52 ENGLAND 4. Billy Slater last night elevated himself into the pantheon of great Australian fullbacks with a blistering attacking performance that left his coach and Kangaroos legend Ricky Stuart grasping for adjectives. Along with Storm teammate and fellow three-try hero Greg Inglis, Slater turned on a once-in-a-season performance to shred England to pieces and leave any challenge to Australia's superiority in tatters. It also came just six days after the birth of his first child, a baby girl named Tyla Rose. Kiwis angry at grapple tackle: The Kiwis are fuming a dangerous grapple tackle on wing Sam Perrett went unpunished in last night's World Cup rugby league match but say they won't take the issue further. Wing Sam Perrett was left lying motionless after the second tackle of the match at Skilled Park, thanks to giant Papua New Guinea prop Makali Aizue. Replays clearly showed Aizue, the Kumuls' cult hero who plays for English club Hull KR, wrapping his arm around Perrett's neck and twisting it. Kiwis flog Kumuls: New Zealand 48 Papua New Guinea NG 6. A possible hamstring injury to Kiwis dynamo Benji Marshall threatened to overshadow his side's big win over Papua New Guinea at Skilled Park last night. Arguably the last superstar left in Stephen Kearney's squad, in the absence of show-stoppers like Roy Asotasi, Frank Pritchard and Sonny Bill Williams, Marshall is widely considered the Kiwis' great white hope. -

NRL Reconciliation Action Plan

Preston Campb ell, “King of the Kids”, in Pormpuraaw , North Queensland NRL Reconciliation Action Plan Message from the Chief Executive Officers Rugby League is a sport for everyone and from its earliest days it has developed a proud association with Indigenous athletes. George Green is recognised as the first Indigenous rugby league player, beginning his career with Eastern Suburbs in 1909. He would become the first in a line of talented Indigenous athletes that has 2 3 carried on for generations. As League enters its Centenary year there can be no doubting the contribution that has been made by champions such as Arthur Beetson, Eric Simms, Larry Corowa, Steve Renouf, Nathan Blacklock, Mal Meninga and Anthony Mundine to name just a few. Today the likes of Matty Bowen, Johnathan Thurston and Greg Inglis are among the 11% of NRL players who proudly boast Indigenous heritage. A sense of the opportunities created through Rugby League is underlined when one considers that Indigenous Australians account for under 3% of Australia’s wider population. 1 4 This Reconciliation Action Plan is a formal recognition of the support that is extended to Indigenous communities by NRL clubs and players and the various arms of the game . It will be monitored by a newly established Reconciliation Action Plan Management Group and will be publicly reported on an annual basis. As well as providing direct material assistance to Indigenous communities, the game’s peak bodies are working in partnership with Reconciliation Australia to keep this RAP alive and ensure it assists in the wider goal of building understanding and positive relationships 5 6 between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians, in the spirit of reconciliation. -

Reconciliation Action Plan 2020– 2023

GOLD COAST TITANS Reconciliation Action plan SEPT 2020– SEPT 2023 ON THE COVER 2020 Gold Coast Titans Indigenous ABOUT THE ARTIST jersey design. Laura Pitt is a 25-year-old from the Gamilaroi The design, titled “Healing”, is the work of tribe, living in Coffs Harbour in northern New artist Laura Pitt. South Wales. The blue circles in the middle with the Pitt has been passionate about telling her symbols on the outside represent the Titans story through art since her childhood and as community. Passion is represented through a football fan was inspired to bring her work to the coloured dots surrounding the players life through sport. and supporters with links of the blue and All Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander artists ochre lines that merge together as one. The were encouraged to submit designs for the handprintes and blue and white waterholes Titans 2020 Indigenous jersey, with all entries surrounding the area represent connection to required to use the Titans’ colours of sea, the land. The blue and yellow healing leaves sand and sky to tell a story about the Club, its represent the resilience of the team that play connection to the region and its commitment together and heal together. to community values. There are messages about healing, support “I wanted to be able to interpret my life and togetherness, with the message about story into the artwork to go onto the jersey, connection with the community a major because it is a really big thing – especially for focus. the Indigenous players at the club,” Pitt said. -

Health and Physical Education

Resource Guide Health and Physical Education The information and resources contained in this guide provide a platform for teachers and educators to consider how to effectively embed important ideas around reconciliation, and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander histories, cultures and contributions, within the specific subject/learning area of Health and Physical Education. Please note that this guide is neither prescriptive nor exhaustive, and that users are encouraged to consult with their local Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander community, and critically evaluate resources, in engaging with the material contained in the guide. Page 2: Background and Introduction to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health and Physical Education Page 3: Timeline of Key Dates in the more Contemporary History of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health and Physical Education Page 5: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health and Physical Education Organisations, Programs and Campaigns Page 6: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Sportspeople Page 8: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health and Physical Education Events/Celebrations Page 12: Other Online Guides/Reference Materials Page 14: Reflective Questions for Health and Physical Education Staff and Students Please be aware this guide may contain references to names and works of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people that are now deceased. External links may also include names and images of those who are now deceased. Page | 1 Background and Introduction to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health and Physical Education “[Health and] healing goes beyond treating…disease. It is about working towards reclaiming a sense of balance and harmony in the physical, psychological, social, cultural and spiritual works of our people, and practicing our profession in a manner that upholds these multiple dimension of Indigenous health” –Professor Helen Milroy, Aboriginal Child Psychiatrist and Australia’s first Aboriginal medical Doctor. -

Parliamentary Debates (Hansard)

PARLIAMENT OF VICTORIA PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES (HANSARD) LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY FIFTY-FIFTH PARLIAMENT FIRST SESSION 14 October 2003 (extract from Book 4) Internet: www.parliament.vic.gov.au/downloadhansard By authority of the Victorian Government Printer The Governor JOHN LANDY, AC, MBE The Lieutenant-Governor Lady SOUTHEY, AM The Ministry Premier and Minister for Multicultural Affairs ....................... The Hon. S. P. Bracks, MP Deputy Premier, Minister for Environment, Minister for Water and Minister for Victorian Communities.............................. The Hon. J. W. Thwaites, MP Minister for Finance and Minister for Consumer Affairs............... The Hon. J. Lenders, MLC Minister for Education Services and Minister for Employment and Youth Affairs....................................................... The Hon. J. M. Allan, MP Minister for Transport and Minister for Major Projects................ The Hon. P. Batchelor, MP Minister for Local Government and Minister for Housing.............. The Hon. C. C. Broad, MLC Treasurer, Minister for Innovation and Minister for State and Regional Development......................................... The Hon. J. M. Brumby, MP Minister for Agriculture........................................... The Hon. R. G. Cameron, MP Minister for Planning, Minister for the Arts and Minister for Women’s Affairs................................... The Hon. M. E. Delahunty, MP Minister for Community Services.................................. The Hon. S. M. Garbutt, MP Minister for Police and Emergency Services -

Legislative Assembly

New South Wales Legislative Assembly PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES (HANSARD) Fifty-Seventh Parliament First Session Tuesday, 4 June 2019 Authorised by the Parliament of New South Wales TABLE OF CONTENTS Notices ................................................................................................................................................. 1061 Presentation ...................................................................................................................................... 1061 Private Members' Statements ............................................................................................................... 1061 Campbelltown-Camden Ghosts Women's Cricket Team ................................................................ 1061 Homelessness ................................................................................................................................... 1061 Senator John "wacka" Williams ....................................................................................................... 1062 Goulburn Electorate ......................................................................................................................... 1063 Light Rail Project ............................................................................................................................. 1064 Glenray Industries ............................................................................................................................ 1064 Strata Committees ........................................................................................................................... -

Redi Long Presiden

Lukim Catholic Saut Bogenvil Reporter Divelopmen Palamen Mas Isu insait... Projek Saplimen INSAIT nius... P2 P11,12,25,26 insait... P16-21 Namba 1856 Wan Wik Mas 11 - 17, 2010 Niuspepa Bilong Yumi Ol PNG Stret! K1 tasol RediRedi long long Presiden... Presiden... Dokta Susilo Bam- bang, Presiden bilong Indonesia. REDI LONG PRESIDEN: Ol Indonesia Difens Fos soldia long Pot Mosbi i redim ol yet long Tunde long makim kamap bilong presiden bilong ol tude, Fonde Mas 11. Paul Zuvani i raitim OPISEL Gavman progrem long kam bilong Pres- iden Dokta Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono bilong Hevi bilong boda Indonesia i bin tok long presiden bai givim tok long ol Memba bilong Palamen long tumora. Tasol dispela bai no inap kamap bihain long ol Memba bilong Palamen i tok nogat long em. pasim Presiden long Wanpela insait man i tokim Wantok Nius olsem dispela em bikos long hevi i kamap long boda namel long Papua Niugini na Wes Papua (Indonesia). bungim ol memba Moa stori long pes 2 P2 Wantok Mas 11 - 17, 2010 palamennius K100 milion mani bilong NADP i paul Koroba Lek Kobiago bai kisim polis opisa Paul Zuvani i raitim trik Sevises Impruvmen Pro- putim ol polis bilong mipela long Memba bilong Nawae 2009 i nogat wanpela Paul Zuvani i raitim grem (DSIP) em na komiti bi- ol haus." Timothy Bonga husat i mani bilong NADP." BUS distrik Koroba Lek Kopi- long en i sanapim pinisim "Mi tok tenk yu olsem yu INAP olsem K100 milion askim sapos NADP i gat "Na dispela hap mani ago long Hela Trensinel Atoriti sampela ol 32 haus na i wetim mekim isi long mipela long mani bilong Nesenel sampela mani yet long em sampela musmus i rijen long Sauten Hailans ol polis long go stap long ol. -

2019 Annual School Report to the Community St Marys Primary

2019 Annual School Report to the Community St Marys Primary School Dubbo 25A Wheelers lane, Dubbo 2830 [email protected] www.stmarysdubbo.nsw.edu.au (02) 68 82 4790 Principal Mr Luke Wilson S O: M K G C Principal's Message On behalf of our school community, I am happy to present the 2019 Annual Report. St Mary’s is a wonderful school and our school vision statement is evident in all aspects of school life. Our school has a strong culture with a focus on learning and living out the gospel values. As well as the innovave and contemporary learning and teaching pracces in the classroom, there were many addional and valuable extra-curricular acvies and programs that took place in 2019 and I am thankful to the staff and parents who coordinated and organised them. 2019 has been a very excing year with our school Rugby League, Debang, Netball, Girls Soccer and Chess teams winning regional compeons. I commend the Parents and Friend's Associaon for their hard work and dedicaon in supporng our school and the teaching and support staff for their professionalism, dedicaon and care and always working together to achieve the best learning outcomes for all students. As Principal I am thankful to all members of our school community for your support, involvement and hard work. May we connue to live our school moo “Christ is My Light” by our words and acons. Parish Priest's Message I am happy to say that St Mary’s is an example of what Catholic schooling should look like. -

4Th Annual Report for the Year Ended 31 October 2009

4TH ANNUAL REPORT FOR THE YEAR ENDED 31 OCTOBER 2009 SOUTH SYDNEY MEMBERS RUGBY LEAGUE FOOTBALL CLUB LTD ACN 118 320 684 ANNUAL REPORT YEAR ENDED 31 OCTOBER 2009 Just one finger. Contents Page 01 Chairman’s Report 3 02 100 Grade Games 4 03 Life Members 6 04 Financials 7 - Directors’ Report 7a, 7b - Lead Auditor’s Independence Declaration 7c - Income Statement - Statement of Recognised Income and Expense 7d - Balance Sheet - Statement of Cash Flow 7e - Discussion and Analysis - Notes to the Financial Statements 7f, 7g - Directors’ Declaration 7h - Audit Report 7h 05 Corporate Partners 8 06 South Sydney District Rugby League Football Club Limited 9 07 NRL Results Premiership Matches 2009 13 NRL Player Record for Season 2009 15 2009 NRL Ladder 15 08 NSW Cup Results 2009 16 09 Toyota Cup Results 2009 17 10 2009 Toyota Cup Ladder 18 The new ‘just one finger’ De–Longhi Primadonna Avant Fully Automatic coffee machine. 2009 Club Awards 18 You would be excited too, with De–Longhi’s range of ‘just one finger’ Fully Automatic Coffee Machines setting a new standard in coffee appreciation. Featuring one touch technology for barista quality Cappuccino, Latte or Flat White, all in the comfort of your own home. All models include automatic cleaning, an in-built quiet grinder and digital programming to personalise your coffee settings. With a comprehensive range to choose from, you’ll be spoilt for choice. www.delonghi.com.au / 1800 126 659 SOUTH SYDNEY MEMBERS RUGBY LEAGUE FOOTBALL CLUB LIMITED 1 ANNUAL REPORT YEAR ENDED 31 OCTOBER 2009 Chairman’s Report 01 My report to Members last year was written In terms of financial performance, I am pleased each of them for the commitment they have on the eve of our return to a renovated and to report that the 2009 year delivered the shown in ensuring that Members’ rights are remodelled Redfern Oval. -

Australia and the Pacific

AUSTRALIA AND THE PACIFIC: THE AMBIVALENT PLACE OF PACIFIC PEOPLES WITHIN CONTEMPORARY AUSTRALIA Scott William Mackay, BA (Hons), BSc July 2018 Submitted in total fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Australian Indigenous Studies Program School of Culture and Communication The University of Melbourne 0000-0002-5889 – Abstract – My thesis examines the places (real and symbolic) accorded to Pacific peoples within the historical production of an Australian nation and in the imaginary of Australian nationalism. It demonstrates how these places reflect and inform the ways in which Australia engages with the Pacific region, and the extent to which Australia considers itself a part of or apart from the Pacific. While acknowledging the important historical and contemporary differences between the New Zealand and Australian contexts, I deploy theoretical concepts and methods developed within the established field of New Zealand- centred Pacific Studies to identify and analyse what is occurring in the much less studied Australian-Pacific context. In contrast to official Australian discourse, the experiences of Pacific people in Australia are differentiated from those of other migrant communities because of: first, Australia’s colonial and neo-colonial histories of control over Pacific land and people; and second, Pacific peoples' important and unique kinships with Aboriginal Australians. Crucially the thesis emphasises the significant diversity (both cultural and national) of the Pacific experience in Australia. My argument is advanced first by a historicisation of Australia’s formal engagements with Pacific people, detailing intersecting narratives of their migration to Australia and Australia’s colonial and neo- colonial engagements within the Pacific region. -

Terry Williams

The Lost Tribes of League THE FATE OF AXED AND MERGED CLUBS AND THEIR FANS Terry Williams 11th Annual Tom Brock Lecture NSW Leagues Club Sydney NSW 23 September 2009 Australian Society for Sports History www.sporthistory.org The Lost Tribes of League: THE FATE OF AXED AND MERGED CLUBS AND THEIR FANS 11th Annual Tom Brock Lecture NSW Leagues Club, Sydney, 23 September 2009 Published in 2010 by the Tom Brock Bequest Committee on behalf of the Australian Society for Sports History. © 2010 by the Tom Brock Bequest Committee and the Australian Society for Sports History. This monograph is copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purposes of private study, research, criticism or review, as permitted under the Copyright Act, no part may be reproduced by any process without written permission from the publisher. ISBN 978-0-9804815-3-2 Back cover image of Tom Brock courtesy of Brian McIntyre. All other images provided by Terry Williams. Thanks are due to the respective owners of copyright for permission to publish these images. Layout and design: Level Playing Field graphic design <[email protected]> Printing: On Demand <[email protected]> Tom Brock Bequest The Tom Brock Bequest, given to the Australian Society for Sports History (ASSH) in 1997, consists of the Tom Brock Collection supported by an ongoing bequest. The Collection, housed at the State Library of New South Wales, includes manuscript material, newspaper clippings, books, photographs and videos on rugby league in particular and Australian sport in general. It represents the finest collection of rugby league material in Australia.