Thurrock's Earliest Freemasons

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Applications and Decisions 24 September 2014

OFFICE OF THE TRAFFIC COMMISSIONER (EAST OF ENGLAND) APPLICATIONS AND DECISIONS PUBLICATION NUMBER: 5036 PUBLICATION DATE: 24 September 2014 OBJECTION DEADLINE DATE: 15 October 2014 Correspondence should be addressed to: Office of the Traffic Commissioner (East of England) Hillcrest House 386 Harehills Lane Leeds LS9 6NF Telephone: 0300 123 9000 Fax: 0113 248 8521 Website: www.gov.uk The public counter at the above office is open from 9.30am to 4pm Monday to Friday The next edition of Applications and Decisions will be published on: 08/10/2014 Publication Price 60 pence (post free) This publication can be viewed by visiting our website at the above address. It is also available, free of charge, via e-mail. To use this service please send an e-mail with your details to: [email protected] APPLICATIONS AND DECISIONS Important Information All correspondence relating to public inquiries should be sent to: Office of the Traffic Commissioner (East of England) Eastbrook Shaftesbury Road Cambridge CB2 8DR The public counter in Cambridge is open for the receipt of documents between 9.30am and 4pm Monday to Friday. There is no facility to make payments of any sort at the counter. General Notes Layout and presentation – Entries in each section (other than in section 5) are listed in alphabetical order. Each entry is prefaced by a reference number, which should be quoted in all correspondence or enquiries. Further notes precede each section, where appropriate. Accuracy of publication – Details published of applications reflect information provided by applicants. The Traffic Commissioner cannot be held responsible for applications that contain incorrect information. -

Template Letter

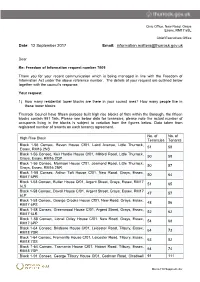

Civic Office, New Road, Grays Essex, RM17 6SL Chief Executives Office Date: 12 September 2017 Email: [email protected] Dear Re: Freedom of Information request number 7005 Thank you for your recent communication which is being managed in line with the Freedom of Information Act under the above reference number. The details of your request are outlined below together with the council’s response. Your request 1) How many residential tower blocks are there in your council area? How many people live in these tower blocks Thurrock Council have fifteen purpose built high rise blocks of flats within the Borough, the fifteen blocks contain 981 flats. Please see below data for tenancies, please note the actual number of occupants living in the blocks is subject to variation from the figures below. Data taken from registered number of tenants on each tenancy agreement. No. of No. of High Rise Block Tenancies Tenants Block 1-56 Consec, Bevan House Cf01, Laird Avenue, Little Thurrock, 51 58 Essex, RM16 2NS Block 1-56 Consec, Keir Hardie House Cf01, Milford Road, Little Thurrock, 50 58 Grays, Essex, RM16 2QP Block 1-56 Consec, Morrison House Cf01, Jesmond Road, Little Thurrock, 50 57 Grays, Essex, RM16 2NR Block 1-58 Consec, Arthur Toft House Cf01, New Road, Grays, Essex, 50 64 RM17 6PR Block 1-58 Consec, Butler House Cf01, Argent Street, Grays, Essex, RM17 51 65 6LS Block 1-58 Consec, Davall House Cf01, Argent Street, Grays, Essex, RM17 47 57 6LP Block 1-58 Consec, George Crooks House Cf01, New Road, Grays, Essex, 48 56 RM17 6PS -

Purfleet Thames Terminal

1/ INTRODUCTION PURPOSE OF WHO ARE C.RO PORTS? WHAT WE DO THE EXHIBITION C.RO Ports operate Purfleet Thames Terminal, a roll-on/roll-off The Purfleet Thames Terminal operates as a roll-on/roll-off We would like to talk to you and we invite your views on our freight terminal in Purfleet. freight terminal (port) for the handling, storage and onward exciting plans for the future of the Purfleet Thames Terminal. movement of trailers, containers, vehicles and general cargo. The land is owned by Purfleet Real Estate Ltd who will be the We have appointed a team to prepare planning applications that Applicant on any future planning applications at the site Ships sail daily direct to and from Rotterdam and Zeebrugge. will be submitted to Thurrock Council for approval by November this year. The port also includes railways which bring and move goods from the site in container and car trains. We are now preparing draft design proposals and would like your feedback at this early stage before they are finalised. Our early ideas are presented in this exhibition and the team are on hand to answer any questions. This isn’t your only chance to comment – the Council will consult on the proposals once the applications are submitted for a period of 21 days. PURFLEET THAMES TERMINAL DRAFT PLANS FOR CONSULTATION PURPOSES AND SUBJECT TO CHANGE 2/ THE PURFLEET THAMES TERMINAL SITE LEGEND The application site includes the land where the Purfleet Thames Terminal operates today and a small number of other A0 surrounding land parcels. -

Martello Close, Little Thurrock, Grays, RM17 6FL Martello Close, Little Thurrock, Grays, RM17 6FL

£425,000* fees apply Martello Close, Little Thurrock, Grays, RM17 6FL Martello Close, Little Thurrock, Grays, RM17 6FL * GUIDE PRICE £425,000 - £450,000 * **** GATED DEVELOPMENT **** 18 HOUSES TO CHOOSE FROM (subject to availability) **** UNDERGROUND PARKING **** Martello Close is a GATED DEVELOPMENT with 18, 4 Bedroom Townhouses, made up of SEMI DETACHED and DETACHED properties. The site is situated in the heart of Thurrock just off Dock Road in Little Thurrock and Ideally placed for local schools, access to the A13 London to Southend trunk road, and bus routes. On site there is parking for approximately 40 cars, which is underground and secured by electric gates. Each property consists of en-suites, plus a further TWO bath/shower rooms, ground floor WC, four DOUBLE BEDROOMS, fitted kitchens with high gloss units and GRANITE work surfaces. You will also have a pick Entrance Hall documentation at a later stage and we would ask for your co- operation in order that there will be no delay in agreeing the Cloakroom sale. Kitchen 2: These particulars do not constitute part or all of an offer or contract. 11'0 x 8'0 (3.35m x 2.44m) 3: The measurements indicated are supplied for guidance only Lounge and as such must be considered incorrect. 16'0 x 15'0 (4.88m x 4.57m) 4: Potential buyers are advised to recheck the measurements before committing to any expense. First Floor Landing 5. Referral Fees - Please note a referral fee of up to £240.00 including VAT per transaction could be received from any Bedroom One referred solicitor upon completion. -

FIVE WELLS, GRAYS, ESSEX RM17 6XR BLOCK FORWARD PURCHASE OPPORTUNITY Five Wells, Grays, 2 Essex RM17 6XR

FIVE WELLS, GRAYS, ESSEX RM17 6XR BLOCK FORWARD PURCHASE OPPORTUNITY Five Wells, Grays, 2 Essex RM17 6XR EXECUTIVE SUMMARY • Centrally located in Grays Town Centre within a five minute • There will be 20 on site car parking spaces. walk of Grays Station. • Practical completion expected in August 2019. • Direct trains to London Fenchurch Street in 32 minutes. • The entire development comes with a six year CML • An opportunity to forward purchase an entire newly compliant warranty. developed block of 26 flats. • We are instructed to seek offers in excess of£5,600,000 • The development will provide 12 x 1 bed, 13 x 2 bed and 1 x 3 (Five Million and Six Hundred Thousand Pounds), subject bed with a total net saleable area of 14,513 sq ft. to contract. Five Wells, Grays, 3 Essex RM17 6XR LOCATION Grays is the largest town in the borough of Thurrock, situated in the county of Essex. The town is 20 miles east of London on the northern side of the River Thames and has a population in the region of 40,000 residents. Housing is considerably more affordable in Grays than in the outer boroughs of the capital, making it a popular destination. Grays is well served by public transport, Grays Railway Station supplies direct access into London Fenchurch Street in 32 minutes and buses operate to many locations including Basildon, Purfleet and Aveley. With excellent road links, the A13 and M25 motorway are both within 2 miles of Grays and provide further access to Essex and Greater London. The Dartford Crossing is situated 3.5 miles to the west and is the busiest estuarial crossing in the UK. -

THOMAS TROTTER Biography

Download as a Word doc THOMAS TROTTER Biography Thomas Trotter is one of Britain’s most widely admired musicians. The excellence of his musicianship is reflected internationally in his musical partnerships. He performs as soloist with, amongst many others, the conductors Sir Simon Rattle, Bernard Haitink, Riccardo Chailly and Sir Charles Mackerras. He has performed in Berlin’s “Philharmonie”, the “Gewandhaus” in Leipzig, the “Concertgebouw” in Amsterdam, the “Musikverein” and the “Konzerthaus” in Vienna and London’s Royal Festival Hall. He has played inaugural concerts in places such as Princeton University Chapel USA, Auckland Town Hall in New Zealand, the Royal Albert Hall London, and Moscow's International Performing Arts Centre. He won the Royal Philharmonic Society award for Best Instrumentalist in 2002, and in 2012 he was named International Performer of the Year by the New York Chapter of the American Guild of Organists. In 2016 he was awarded the Gold Medal of the Royal College of Organists for his achievements in organ playing. Thomas Trotter was appointed Birmingham City Organist in 1983 in succession to Sir George Thalben-Ball, and he is also Organist at St Margaret’s Church, Westminster Abbey and Visiting Fellow in Organ Studies at the Royal Northern College of Music. Earlier in his career he was organ scholar at King’s College, Cambridge, winning the First Prize at the St Albans International Organ Competition in his final year. He received an Honorary Doctorate from Birmingham City University in 2003 and from Birmingham University in 2006. Alongside his regular recitals in Birmingham, Thomas Trotter tours on four continents and plays at many international festivals such as Bath, Salzburg, and the BBC Proms. -

Choral Secular Music Through the Ages

Choral Secular Music through the ages The Naxos catalogue for secular choral music is such a rich collection of treasures, it almost defi es description. All periods are represented, from Adam de la Halle’s medieval romp Le Jeu de Robin et Marion, the earliest known opera, to the extraordinary fusion of ethnic and avant-garde styles in Leonardo Balada’s María Sabina. Core repertoire includes cantatas by J.S. Bach, Beethoven’s glorious Symphony No. 9, and a “must have” (Classic FM) version of Carl Orff’s famous Carmina Burana conducted by Marin Alsop. You can explore national styles and traditions from the British clarity of Elgar, Finzi, Britten and Tippett, to the stateside eloquence of Eric Whitacre’s “superb” (Gramophone) choral program, William Bolcom’s ‘Best Classical Album’ Grammy award winning William Blake songs, and Samuel Barber’s much loved choral music. Staggering emotional range extends from the anguish and passion in Gesualdo’s and Monteverdi’s Madrigals, through the stern intensity of Shostakovich’s Execution of Stepan Razin to the riot of color and wit which is Maurice Saylor’s The Hunting of the Snark. Grand narratives such as Handel’s Hercules and Martinů’s Epic of Gilgamesh can be found alongside tender miniatures by Schubert and Webern. The Naxos promise of uncompromising standards of quality at affordable prices is upheld both in performances and recordings. You will fi nd leading soloists and choirs conducted by familiar names such as Antoni Wit, Gerard Schwarz, Leonard Slatkin and Robert Craft. There is also a vast resource of collections available, from Elizabethan, Renaissance and Flemish songs and French chansons to American choral works, music for children, Red Army Choruses, singing nuns, and Broadway favorites – indeed, something for everyone. -

Rainham Marshes a Special Place for Nature

chalky conditions. chalky the amazing range of wildlife that thrives in in thrives that wildlife of range amazing the discover to place brilliant a is quarry former This essexwt.org.uk/reserves/chafford-gorges Tel: 01375 484016 (10 miles) miles) (10 484016 01375 Tel: Thurrock RM16 6RG 6RG RM16 Thurrock Chafford Gorges Nature Park, Grays Grays Park, Nature Gorges Chafford reserve and stock up in the shop. shop. the in up stock and reserve our café, wander the trails around our nature nature our around trails the wander café, our mammals. Go and discover the fabulous wildlife. fabulous the discover and Go mammals. from our visitor centre, enjoy some hot food in in food hot some enjoy centre, visitor our from teeming with waders, ducks, minibeasts and and minibeasts ducks, waders, with teeming Now you too can enjoy the amazing views views amazing the enjoy can too you Now South Essex has a collection of nature reserves reserves nature of collection a has Essex South (16 miles) rspb.org.uk/southessex miles) (16 from development. from Tel: 01268 498620 01268 Tel: 4UH SS16 Essex Basildon, for nearly 100 years and inadvertently saved it it saved inadvertently and years 100 nearly for Visitor Centre, Wat Tyler Country Park, Park, Country Tyler Wat Centre, Visitor salty Thames. The Ministry of Defence used it it used Defence of Ministry The Thames. salty RSPB South Essex Wildlife Garden and and Garden Wildlife Essex South RSPB marsh since its original reclamation from the the from reclamation original its since marsh freshwater medieval this on changed has Little attractions: local Other In this area… this In year, from all over the world. -

Rectory Road, West Tilbury, Tilbury, RM18 8UD Rectory Road, West Tilbury, Tilbury, RM18 8UD

£1,195 * fees apply Rectory Road, West Tilbury, Tilbury, RM18 8UD Rectory Road, West Tilbury, Tilbury, RM18 8UD Located in the centre of West Tilbury village this three bedroom cottage commands lovely views over open countryside and benefits from a large garden that surrounds the property. Fitted kitchen, downstairs cloakroom, quiet position. Available NOW Due to the present restrictions on movement put in place by the Government to halt the spread of (C0VID-19), we are unable to arrange physical viewings, please e-mail the office to register your interest and we will be in contact as soon as restrictions are lifted - Thank you and STAY SAFE. ** IMPORTANT NOTICE FOR ALL INTERESTED BEFORE any stoppages and must also be a UK PARTIES** homeowner. Immigration checks may be required to be ** IMPORTANT NOTICE FOR ALL INTERESTED undertaken by the Agent / Landlord on any or all occupants PARTIES** to comply with the Immigration Act 2014. Application for tenancy ( From 01/06/2019) Tenancy application terms and conditions can be found in Should you choose a property through Griffin, you will need our office and online at : to visit the offices ( 4/6 Queensgate Centre, Orsett Road, www.griffin-grays.co.uk Grays, Essex, RM17 5DF) . Terms and conditions apply. Energy Performance You will be asked to pay a holding fee of 1 weeks agreed Certificates Are Available Upon Request. rent price. This will be held for a period of 15 days. You have 15 days to successfully complete the referencing Client Money Protection: Property Mark - Scheme Member procedure. If successful, you will be permitted to allocate No: C0129352 the holding fee ( 1 weeks rent) to your first months rent Redress Scheme: The Property Ombudsman ( TPO) upon move in. -

Bus Route Subsidised/De Minimus Surgery Name Surgery Address 11

Bus route Subsidised/De Minimus Appendix A - List of Health Facilities served by bus routes Surgery Name Surgery Address 11 Subsidised Aveley Medical Centre Aveley Medical Centre, 22 High Street, Aveley, Essex, RM15 4AD 11 Subsidised Pear Tree Surgery 4 West Road, South Ockendon, Essex, RM15 6PR 11 Subsidised Purfleet Care Centre Tank Hill Road, Purfleet, Essex, RM19 1SX 11 Subsidised Sancta Maria Centre Sancta Maria Centre, Daiglen Drive, South Ockendon, Essex, RM15 5SZ 11 Subsidised The Health Centre Crammavill Street, Stifford Clays, Grays, Essex. RM16 2AP 11 Subsidised The Health Centre Darenth Lane, South Ockendon, Essex, RM15 5LP 11 Subsidised The Surgery 63 Rowley Road, Orsett, Essex. RM16 3ET 11 Subsidised Chadwell Medical Centre 1 Brentwood Road, Chadwell St. Mary, Essex, RM16 4JD 11 Subsidised Basildon Hospital Nethermayne, Basildon, SS16 5NL 11 Subsidised Orsett Hospital Rowley Road, Orsett, Grays, RM16 3EU 11 Subsidised Thurrock Community Hospital Long Lane, Grays, Essex, RM16 2PX 33 De Minimis Chafford Hundred Medical Centre Drake Road, Chafford Hundred RM16 6RS 33 De Minimis The Thurrock Health Centre 55-57 High St, Town Centre, Grays, Thurrock RM17 6NJ 66 De Minimis Branch Surgery 57 Calcutta Road, Tilbury, RM18 7QZ 66 De Minimis East Thurrock Medical Centre 34 East Thurrock Road, Grays, Essex, RM17 6SP 66 De Minimis Main Surgery 4 St. Chad's Road, Tilbury, Essex. RM18 8LA 66 De Minimis Sai Medical Cebtre 105 Calcutta Road, Tilbury, Essex. RM18 7QA 66 De Minimis The Health Centre London Road, Tilbury, Essex. RM18 8EB 66 De Minimis Chadwell Medical Centre 1 Brentwood Road, Chadwell St. Mary, Essex, RM16 4JD 66 De Minimis The Thurrock Health Centre 55-57 High St, Town Centre, Grays, Thurrock RM17 6NJ 201 Subsidised Branch Surgery 2 Wharf Road, Stanford-le-Hope, Essex, SS17 0BZ 201 Subsidised Branch Surgery 271a Southend Road, Stanford-le-Hope, Essex. -

Internal Draft Version June 2006)

(Internal Draft Version June 2006) THURROCK LOCAL DEVELOPMENT FRAMEWORK (LDF) SITE SPECIFIC ALLOCATIONS AND POLICIES “ISSUES AND OPTIONS” DEVELOPMENT PLAN DOCUMENT [DPD] INFORMAL CONSULTATION DRAFT CONTENTS Page 1. INTRODUCTION 1 2. STRATEGIC & POLICY CONTEXT 4 3. CHARACTERISTICS OF THE BOROUGH 6 4. KEY PRINCIPLES 7 5. RELATIONSHIP WITH CORE STRATEGY VISION, 7 OBJECTIVES & ISSUES 6. SITE SPECIFIC PROVISIONS 8 7. MONITORING & IMPLEMENTATION 19 8. NEXT STEPS 19 APPENDICES 20 GLOSSARY OF TERMS REFERENCE LIST INTERNAL DRAFT VERSION JUNE 2006 1. INTRODUCTION 1.1 We would like to get your views on future development and planning of Thurrock to 2021. A new system of “Spatial Planning” has been introduced that goes beyond traditional land-use planning and seeks to integrate the various uses of land with the various activities that people use land for. The new spatial plans must involve wider community consultation and involvement and be based on principles of sustainable development. 1.2 The main over-arching document within the LDF portfolio is the Core Strategy. This sets out the vision, objectives and strategy for the development of the whole area of the borough. The Site Specific Allocations and Policies is very important as it underpins the delivery of the Core Strategy. It enables the public to be consulted on the various specific site proposals that will guide development in accordance with the Core Strategy. 1.3 Many policies in the plans will be implemented through the day-to-day control of development through consideration of planning applications. This document also looks at the range of such Development Control policies that might be needed. -

475 Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

475 bus time schedule & line map 475 Stanford Le Hope - Tilbury - Grays - Orsett - View In Website Mode Brentwood The 475 bus line (Stanford Le Hope - Tilbury - Grays - Orsett - Brentwood) has 2 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Brentwood: 7:04 AM (2) Stanford Le Hope: 3:30 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest 475 bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next 475 bus arriving. Direction: Brentwood 475 bus Time Schedule 49 stops Brentwood Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday Not Operational Monday 7:04 AM Rookery Corner, Stanford Le Hope Tuesday 7:04 AM Buckingham Hill Road, Stanford Le Hope Wednesday 7:04 AM Sandown Road, Orsett Thursday 7:04 AM Sandown Close, England Friday 7:04 AM Grosvenor Road, Orsett Saturday Not Operational Orsett Cock Ph, Orsett Brentwood Road, Chadwell St Mary Felicia Way, Chadwell St Mary 475 bus Info St Teresa Walk, England Direction: Brentwood Stops: 49 Gateway Academy, Chadwell St Mary Trip Duration: 71 min Line Summary: Rookery Corner, Stanford Le Hope, Handel Crescent, Tilbury Buckingham Hill Road, Stanford Le Hope, Sandown Road, Orsett, Grosvenor Road, Orsett, Orsett Cock Ph, Orsett, Brentwood Road, Chadwell St Mary, Raphael Avenue, Tilbury Felicia Way, Chadwell St Mary, Gateway Academy, Chadwell St Mary, Handel Crescent, Tilbury, Raphael Christchurch Road, Tilbury Avenue, Tilbury, Christchurch Road, Tilbury, Calcutta Christchurch Road, Tilbury Road, Tilbury, Toronto Road, Tilbury, Railway Station, Tilbury, Russell Road, Tilbury, The Willows, Grays, Calcutta Road,