Industry Or Holy Vocation? When Shehitah and Kashrut Entered the Public Sphere in the United States During the Age of Reform

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

TEMPLE ISRAEL OP HOLLYWOOD Preparing for Jewish Burial and Mourning

TRANSITIONS & CELEBRATIONS: Jewish Life Cycle Guides E EW A TEMPLE ISRAEL OP HOLLYWOOD Preparing for Jewish Burial and Mourning Written and compiled by Rabbi John L. Rosove Temple Israel of Hollywood INTRODUCTION The death of a loved one is so often a painful and confusing time for members of the family and dear friends. It is our hope that this “Guide” will assist you in planning the funeral as well as offer helpful information on our centuries-old Jewish burial and mourning practices. Hillside Memorial Park and Mortuary (“Hillside”) has served the Southern California Jewish Community for more than seven decades and we encourage you to contact them if you need assistance at the time of need or pre-need (310.641.0707 - hillsidememorial.org). CONTENTS Pre-need preparations .................................................................................. 3 Selecting a grave, arranging for family plots ................................................. 3 Contacting clergy .......................................................................................... 3 Contacting the Mortuary and arranging for the funeral ................................. 3 Preparation of the body ................................................................................ 3 Someone to watch over the body .................................................................. 3 The timing of the funeral ............................................................................... 3 The casket and dressing the deceased for burial .......................................... -

Orthodoxy in American Jewish Life1

ORTHODOXY IN AMERICAN JEWISH LIFE1 by CHARLES S. LIEBMAN INTRODUCTION • DEMOGRAPHIC CHARACTERISTICS OF ORTHODOXY • EARLY ORTHODOX COMMUNITY • UNCOMMITTED ORTHODOX • COM- MITTED ORTHODOX • MODERN ORTHODOX • SECTARIANS • LEAD- ERSHIP • DIRECTIONS AND TENDENCIES • APPENDLX: YESHIVOT PROVIDING INTENSIVE TALMUDIC STUDY A HIS ESSAY is an effort to describe the communal aspects and institutional forms of Orthodox Judaism in the United States. For the most part, it ignores the doctrines, faith, and practices of Orthodox Jews, and barely touches upon synagogue hie, which is the most meaningful expression of American Orthodoxy. It is hoped that the reader will find here some appreciation of the vitality of American Orthodoxy. Earlier predictions of the demise of 11 am indebted to many people who assisted me in making this essay possible. More than 40, active in a variety of Orthodox organizations, gave freely of their time for extended discussions and interviews and many lay leaders and rabbis throughout the United States responded to a mail questionnaire. A number of people read a draft of this paper. I would be remiss if I did not mention a few by name, at the same time exonerating them of any responsibility for errors of fact or for my own judgments and interpretations. The section on modern Orthodoxy was read by Rabbi Emanuel Rackman. The sections beginning with the sectarian Orthodox to the conclusion of the paper were read by Rabbi Nathan Bulman. Criticism and comments on the entire paper were forthcoming from Rabbi Aaron Lichtenstein, Dr. Marshall Ski are, and Victor Geller, without whose assistance the section on the number of Orthodox Jews could not have been written. -

Product Directory 2021

STAR-K 2021 PESACH DIRECTORY PRODUCT DIRECTORY 2021 HOW TO USE THE PRODUCT DIRECTORY Products are Kosher for Passover only when the conditions indicated below are met. a”P” Required - These products are certified by STAR-K for Passover only when bearing STAR-K P on the label. a/No “P” Required - These products are certified by STAR-K for Passover when bearing the STAR-K symbol. No additional “P” or “Kosher for Passover” statement is necessary. “P” Required - These products are certified for Passover by another kashrus agency when bearing their kosher symbol followed by a “P” or “Kosher for Passover” statement. No “P” Required - These products are certified for Passover by another kashrus agency when bearing their kosher symbol. No additional “P” or “Kosher for Passover” statement is necessary. Please also note the following: • Packaged dairy products certified by STAR-K areCholov Yisroel (CY). • Products bearing STAR-K P on the label do not use any ingredients derived from kitniyos (including kitniyos shenishtanu). • Agricultural products listed as being acceptable without certification do not require ahechsher when grown in chutz la’aretz (outside the land of Israel). However, these products must have a reliable certification when coming from Israel as there may be terumos and maasros concerns. • Various products that are not fit for canine consumption may halachically be used on Pesach, even if they contain chometz, although some are stringent in this regard. As indicated below, all brands of such products are approved for use on Pesach. For further discussion regarding this issue, see page 78. PRODUCT DIRECTORY 2021 STAR-K 2021 PESACH DIRECTORY BABY CEREAL A All baby cereal requires reliable KFP certification. -

Israel of America, 5 Beekman Street, New York, N

FIFTY CENTS VOL. 2 No. 3 DECEMBER 1964 I TEVES 5725 THE "American Orthodoxy" Yesterday and Today • The Orthodox Jew and The Negro Revolution •• ' The Professor' and Bar Ilan • Second Looks at The Jewish Scene THE JEWISH QBSERVER contents articles "AMERICAN ORTHODOXY" I YESTERDAY AND TODAY, Yaakov Jacobs 3 A CENTRAL ORTHODOX AGENCY, A Position Paper .................... 9 HARAV CHAIM MORDECAI KATZ, An Appreciation ........................ 11 THE JEWISH OBSERVER is published monthly, except July and August, ASPIRATION FOR TORAH, Harav Chaim Mordecai Katz 12 by the Agudath Israel of America, 5 Beekman Street, New York, N. Y. 10038. Second class postage paid at New York, N. Y. THE ORTHODOX JEW AND THE NEGRO REVOLUTION, Subscription: $5.00 per year; single copy: 50¢. Printed in the Marvin Schick 15 U.S.A. THE PROFESSOR AND BAR JI.AN, Meyer Levi .................................... 18 Editorial Board DR. ERNST L. BODENHFJMER Chairman RABBI NATHAN BULMAN RABBI JOSEPH ELIAS JOSEPH FRIEDENSON features RABBI MORRIS SHERER Art Editor BOOK REVIEW ................................................. 20 BERNARD MERI.ING Advertising Manager RABBI SYSHE HESCHEL SECOND LOOKS AT THE JEWISH SCENE ................................................... 22 Managing Editor RABBI Y AAKOV JACOBS THE JEWISH OBSERVER does not assume responsibility for the Kashrus of any product or service the cover advertised in its pages. HARAV CHAIM MORDECAI KATZ dedicating the new dormitory of the Telshe DEC. 1964 VOL. II, No. 3 Yeshiva, and eulogizing the two young students who perished in the fire ~'@> which destroyed the old structure. (See AN APPRECIATION on page 11, and ASPIRATION FOR TORAH on page 12.) OrthudoxJudaism in ih~ Uniied States in our ··rei~oval oi the women's gallery; or th;c~nfirma~· · . -

Labor, Immigration, and the Search for a New Common Ground in the Wake of Iowa's Meatpacking Raids

University of Miami Business Law Review Volume 18 Issue 2 Volume 18 Number 2 (2010) Article 5 July 2010 Still in 'The Jungle': Labor, Immigration, and the Search for a New Common Ground in the Wake of Iowa's Meatpacking Raids Khari Taustin Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.law.miami.edu/umblr Part of the Immigration Law Commons, and the Labor and Employment Law Commons Recommended Citation Khari Taustin, Still in 'The Jungle': Labor, Immigration, and the Search for a New Common Ground in the Wake of Iowa's Meatpacking Raids, 18 U. Miami Bus. L. Rev. 283 (2010) Available at: https://repository.law.miami.edu/umblr/vol18/iss2/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at University of Miami School of Law Institutional Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of Miami Business Law Review by an authorized editor of University of Miami School of Law Institutional Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STILL IN 'THE JUNGLE': LABOR, IMMIGRATION, AND THE SEARCH FOR A NEW COMMON GROUND IN THE WAKE OF IOWA'S MEATPACKING RAIDS KHARI TAUSTIN* I. INTRODUCTION .................................... 283 II. THE LABOR MOVEMENT AND IMMIGRATION LAws ............. 286 A. The Immigration Reform and Control Act ...... ......... 287 B. Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant ResponsibilityAct... 290 1. Basic Provisions ............................. 290 2. Concerns with IRIRA's Application ........... ..... 291 C. FairLabor StandardsAct................ ............. 294 D. Hoffman Plastic Compounds, Inc. v. NLRB..... ..... 296 III. THE MEATPACKING INDUSTRY: HISTORY, DEVELOPMENT, AND TRANSFORMATION ........................ ...... 299 A. The History of Unions and the Searchfor a New Model......... -

Rabbi Haskel Lookstein Advanced to Rank of Associate Rabbi

Rabbi Haskel Lookstein Advanced To Rank Of Associate Rabbi Five years ago, Rabbi Haskel Look¬ stein was elected Assistant Rabbi of The Kehilath Jeshurun family Kehilath Jeshurun. Last week, the Board of Trustees of the congregation voted to promote him to the status of is bowed in at grief the passing of the immortal Associate Rabbi of our congregation. President of the United States JOHN F. KENNEDY KEHILATH JESHURUN MOURNS RABBI JOSEPH H. LOOKSTEIN A TRAGIC EVENT ON NATIONWIDE T.V. PROGRAM The assassination of John F. Kennedy Rabbi Joseph H. Lookstein partici¬ last Friday led to a series of memorial pated in a one hour panel discussion on events which were quickly arranged ihe Columbia television network last for by our congregation. Sunday morning. His fellow panelists were outstanding representatives of At the conclusion of the Friday eve¬ the three major faiths in America. The service, while the deed was so ning discussion centered around the assas¬ fresh in our minds as to be unreal, sination of President Kennedy. Rabbi Rabbi Joseph hi. Lookstein spoke brief¬ Lookstein's remarks, some of which can ly about the meaning of the tragedy be found elsewhere in this bulletin, and pronounced a special benediction. were devoted primarily to the moral Rabbi Haskel Lookstein climate which exists in this On Saturday morning, the Rabbi set country. aside his announced sermon topic and We are proud that our Rabbi was Mr. Max J. Etra, on behalf of the devoted the sermon period to a re¬ singled out as one of the participants officers, proposed the promotion to ligious analysis of the event and of its in the program. -

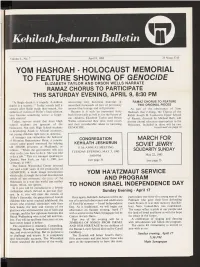

Kehilathjeshurunbulletin ©

KehilathjeshurunBulletin © Volume L, No. 7 April 8, 1983 25 Nisan 5743 YOM HASHOAH ■ HOLOCAUST MEMORIAL TO FEATURE SHOWING OF GENOCIDE ELIZABETH TAYLOR AND ORSON WELLS NARRATE RAMAZ CHORUS TO PARTICIPATE THIS SATURDAY EVENING, APRIL 9, 8:30 PM RAMAZ CHORUS TO FEATURE "A Single death is a tragedy. A million uncovering new historical material. It TWO ORIGINAL PIECES deaths is a statistic." Today, nearly half a unearthed thousands of feet of previously century after Stalin made that remark, the unseen film footage and still pictures. As part of the observance of Yom millions of victims of Hitler's final solution Because it is such an important story Hashoah that evening, the Chorus of the have become something worse: a forget¬ both historically as well as for the future of Rabbi Joseph H. Lookstein Upper School table statistic! our children, Elizabeth Taylor and Orson of Ramaz, directed by Michael Berl, will Today, surveys reveal that most High Welles volunteered their time, their voices present choral selections appropriate to the School students are ignorant of the and their considerable talent in narrating Holocaust. Included in these will be two Holocaust. Not only High School students GENOCIDE. (continued on page 3) in developing Asian or African countries, but young children right here in America. A teenager can rationalize the behavior CONGREGATION MARCH FOR of Hermine Braunsteiner Ryan, a concen¬ KEHILATH JESHURUN tration camp guard sentenced for helping SOVIET JEWRY kill 100,000 prisoners at Majdanek, as lllth ANNUAL MEETING follows: "When the government tells you SOLIDARITY SUNDAY TUESDAY EVENING, MAY 3, 1983 what to do, you have to do it. -

Speaker Materials

Speaker Materials Partnering organizations: The Akdamut – an Aramaic preface to our Torah Reading Rabbi Gesa S. Ederberg ([email protected]) ַאְקָדּמוּת ִמִלּין ְוָשָׁריוּת שׁוָּת א Before reciting the Ten Commandments, ַאְוָלא ָשֵׁקְלָא ַהְרָמןְוּרשׁוָּת א I first ask permission and approval ְבָּבֵבי ְתֵּרי וְּתַלת ְדֶאְפַתְּח בּ ַ ְקשׁוָּת א To start with two or three stanzas in fear ְבָּבֵרְי דָבֵרי ְוָטֵרי ֲעֵדי ְלַקִשּׁישׁוָּת א Of God who creates and ever sustains. ְגּבָוּרן ָעְלִמין ֵלהּ ְוָלא ְסֵפק ְפִּרישׁוָּת א He has endless might, not to be described ְגִּויל ִאְלּוּ רִקיֵעי ְק ֵ ָי כּל חְוּרָשָׁת א Were the skies parchment, were all the reeds quills, ְדּיוֹ ִאלּוּ ַיֵמּי ְוָכל ֵמיְכִישׁוָּת א Were the seas and all waters made of ink, ָדְּיֵרי ַאְרָעא ָסְפֵרי ְוָרְשֵׁמַי רְשָׁוָת א Were all the world’s inhabitants made scribes. Akdamut – R. Gesa Ederberg Tikkun Shavuot Page 1 of 7 From Shabbat Shacharit: ִאלּוּ פִ יוּ מָ לֵא ִשׁיָרה ַכָּיּ ם. וּלְשׁו ֵוּ ִרָנּה כַּהֲמון גַּלָּיו. ְושְפתוֵתיוּ ֶשַׁבח ְכֶּמְרֲחֵבי ָ רִקיַע . וְעֵיֵיוּ ְמִאירות ַכֶּשֶּׁמ שׁ ְוַכָיֵּרַח . וְ יָדֵ יוּ פְ רוּשות כְּ ִ ְשֵׁרי ָשָׁמִי ם. ְוַרְגֵליוּ ַקלּות ָכַּאָיּלות. ֵאין אֲ ַ ְחוּ ַמְסִפּיִקי ם לְהודות לְ ה' אֱ להֵ יוּ וֵאלהֵ י ֲאבוֵתיוּ. וְּלָבֵר ֶאת ְשֶׁמ עַל ַאַחת ֵמֶאֶלף ַאְלֵפי אֲלָ ִפי ם ְוִרֵבּי ְרָבבות ְפָּעִמי ם Were our mouths filled with song as the sea, our tongues to sing endlessly like countless waves, our lips to offer limitless praise like the sky…. We would still be unable to fully express our gratitude to You, ADONAI our God and God of our ancestors... Akdamut – R. Gesa Ederberg Tikkun Shavuot Page 2 of 7 Creation of the World ֲהַדר ָמֵרי ְשַׁמָיּא ְו ַ שׁ ִלְּיט בַּיֶבְּשָׁתּ א The glorious Lord of heaven and earth, ֲהֵקים ָעְלָמא ְיִחָידאי ְוַכְבֵּשְׁהּ בַּכְבּשׁוָּת א Alone, formed the world, veiled in mystery. -

Supreme Court, U.S. FILED LINDA LEBOON, LANCASTER JEWISH

Supreme Court, U.S. No. FILED LINDA LEBOON, Petitioner, LANCASTER JEWISH COMMUNITY CENTER ASSOCIATION, Respondent. On Petition for a Writ of Certiorari to the United States Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit PETITION FOR WRIT OF CETIORARI J. Michael Considine, Jr. John W. Whitehead Counsel of Record Douglas R. McKusick 12 East Barnhard Street THE RUTHERFORD INSTITUTE Suite 100 1440 Sachem Place West Chester, PA 19382 Charlottesville, VA 22901 (610) 431-3288 (434) 978-3888 Participating Attorney for The Rutherford Institute Counsel for Petitioner LANTAGNE LEGAL PRINTING 801 East Main Street Suite 100 Richmond, Virginia 23219 (800) 847-0477 QUESTIONS PRESENTED 1. Where an organization is not controlled by a church, synagogue, board of elders or rabbis (none of whom are on its independent board), is not funded by a church, synagogue or religious organization, was granted a tax-exemption as an educational (not a religious) organization, did not require staff to adhere to any code of beliefs or behavior based on its religion, all of whose federal and state filings indicate its purposes are other than religious, and agreed to a United Way policy banning religious discrimination, is it entitled to a religious exemption in a matter in which an employee with an excellent work record was fired for attending Messianic worship at her Protestant church? 2. Should the court grant certiorari because the lower court’s decision conflicts with cases in the Third, Little v. Wuerl, 929 F.2d 944, 951 (3rd Cir. 1991), Fourth, Shaliehsabou v. Hebrew Home of Washington, 363 F.3d 299 (4th Cir. -

The Following Report Is No Longer Current, and Is to Be Used for Historical Purposes Only

The following report is no longer current, and is to be used for historical purposes only. CRIMES WITHOUT CONSEQUENCES: The Enforcement of Humane Slaughter Laws in the United States Researched and written by DENA JONES for the Animal Welfare Institute 2 CRIMES WITHOUT CONSEQUENCES: The Enforcement of Humane Slaughter Laws in the United States Researched and written by Dena Jones May 2008 Animal Welfare Institute Crimes Without Consequences: The Enforcement of Humane Slaughter Laws in the United States Researched and written by Dena Jones Animal Welfare Institute P.O. Box 3650 Washington, DC 20027 www.awionline.org Copyright © 2008 by the Animal Welfare Institute Printed in the United States of America ISBN 0-938414-94-1 LCCN 2008925385 i CONTENTS Executive Summary .................................................................................... 1 1. Introduction ............................................................................................. 5 1.1 About the author........................................................................ 6 1.2 About the Animal Welfare Institute ........................................... 6 1.3 Acknowledgements ................................................................... 6 2. Overview of Food Animal Slaughter in the United States ...................... 7 2.1 Animals Slaughtered ................................................................. 7 2.2 Types of Slaughter Plants .......................................................... 12 2.3 Number of Plants ..................................................................... -

Hidden Sparks

SLINGSHOT CONTACT Rebecca Neuwirth BOARD CHAIR Matthew Bronfman PHONE 212-891-1403 A RESOURCE GUIDEBUDGET $520,000 EMAIL [email protected] INCEPTION 2005 SLINGSHOT FOR JEWISH INNOVATION MEET THE INNOVATORS: INNOVATORS: THE MEET the from for video messages www.slingshotfund.org/videos Visit in Jewish and life. projects organizations innovative most the of leaders introduction why do we create Slingshot? This is the ninth annual edition of Slingshot. So, here’s your homework assignment: Creating this guide takes nearly a year of evaluation, due diligence, discussion, and 1. Read this book and find a project that design. Slingshot represents the combined excites you. Then reach out to its leaders! If effort of nearly 100 people across North you are a participant, a volunteer, or a funder, America, and it costs an arm and a leg to you are what they need in order to grow. print. And then, we give it away for free. 2. Share this book with someone who Why? doesn’t find Jewish life personally relevant. Visit www.slingshotfund.org/order, and order Because the following pages include an that person a free copy. important story about the Jewish community, and we want you to read it – and share it. 3. Discuss this book with your family, Slingshot ’13-’14 tells the narrative of how friends, and colleagues. Slingshot is the Jewish community can remain relevant intended to be a conversation starter: Ask and thrive as the world changes around your parent to pick a favorite organization, it. Over the following pages, you will read and talk about why. -

Iying¹wxt¹lretd¹z@¹Xkeyd

IYING¹WXT¹LRETD¹Z@¹XKEYD ])8U| vO)[{Nz8[(T{C)[{Nz8.wTwSRLxLzD)2yU ])8U| vOOxU)5|G]wC[xN)9|G :@¹DPYN¹¹fol. 44c )[{Nz8P)Z{QzOP)Z{2yQ.wTwSRLxLOw:]LyD{JLyO[xDvUvG)O[|Q{Cw:Ly5O|UV|C]w[wJ|CG{NC{OzQ)2yU [{<(Q Mishnah 1: If somebody hires a worker to work for him on libation wine, his wages are forbidden1. If he hired him for other work, even though he told him, transport an amphora of libation wine for me from one place to another, his wages are permitted2. 1 If a Gentile hires a Jewish worker fact that libation wine is forbidden for specifically to work on his wine, the wages usufruct for a Jewish owner. are forbidden to the worker for all usufruct. 2 The moment that libation wine was not The rule which makes it impossible for the mentioned at the time of the hiring, there is Jewish worker to be hired in this way is no obligation on the worker to refrain from purely rabbinical; it is not implied by the being occupied with libation wine. i¦A¦x m¥W§a Ed¨A©` i¦A¦x .Fl o¥zFp `Ed Fx¨k§U `Ÿl§e .'lek l¥rFRd © z¤` x¥kFVd © :@¹DKLD (44c line 50) .EdEq¨p§w q¨p§w .o¨p¨gFi zFxi¥t§A .`xi ¨r§ ¦ f i¦A¦x x©n¨` .zi¦ria§ ¦ U o¨x¨k§U zi¦ria§ ¦ X©A oi¦UFrdÎl¨ ¨ k§e mit¨ ¦ Y©M©d§emi¦ x¨O©g©d .i¥P©Y x¨k¨W oi¦l§hFp Ed§i `ŸNW ¤ i`©P©i i¦A¦x zi¥a§C oi¥Ni¦`§l o¨p¨gFi i¦A¦x i¥xFdc § `i¦d©d§e .`¨zi¦p§z©n `id ¦ x¥zid ¥ d¨x¨f d¨cFa£r zFxi¥t§A .i©li¦i iA¦ ¦ x x©n¨` .oFd§li¥ xFd d¨i§n¤g§p i¦A¦x§kE dcEd§i ¨ i¦A¦x§M zFr¨n `¨N¤` o¦i©i o¤dici ¥ A ¦ .EdEq¨p§w q¨p§w K¤q¤p o¦i©i§A .o¨p¨gFi i¦A¦x m¥W§a Ed¨A©` i¦A¦x x©n¨c§M .`¨zi¦p§z©n `i¦d Halakhah 1: “If somebody hires a worker,” etc.