The California Volcano Observatory—Monitoring the State's

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Warm Storage for Arc Magmas SEE COMMENTARY

Warm storage for arc magmas SEE COMMENTARY Mélanie Barbonia,1, Patrick Boehnkea, Axel K. Schmittb, T. Mark Harrisona,1, Phil Shanec, Anne-Sophie Bouvierd, and Lukas Baumgartnerd aDepartment of Earth, Planetary, and Space Sciences, University of California, Los Angeles, CA 90095; bInstitute of Earth Sciences, Heidelberg University, 69120 Heidelberg, Germany; cSchool of Environment, The University of Auckland, 1142 Auckland, New Zealand; and dInstitute of Earth Sciences, University of Lausanne, 1015 Lausanne, Switzerland Contributed by T. Mark Harrison, September 28, 2016 (sent for review August 2, 2016; reviewed by George Bergantz and Jonathan Miller) Felsic magmatic systems represent the vast majority of volcanic volumes outweigh their extrusive counterparts is sufficient rea- activity that poses a threat to human life. The tempo and son to assume that both may record different aspects of the magnitude of these eruptions depends on the physical conditions reservoir’s history (15–19); this is because melt-dominated volcanic under which magmas are retained within the crust. Recently the rocks may only represent a volumetrically minor part of the magma case has been made that volcanic reservoirs are rarely molten and reservoir, whereas plutonic rocks represent conditions in the crystal- only capable of eruption for durations as brief as 1,000 years dominated bulk of the magma reservoir (18). To provide a physical following magma recharge. If the “cold storage” model is generally context for our interpretive scheme, we point to simulations of applicable, then geophysical detection of melt beneath volcanoes is Bergantz et al. (19) that show that the full extent of thermal ex- likely a sign of imminent eruption. -

Volcanic Ash and Aviation Safety: Proceedings of the First International Symposium on Volcanic Ash and Aviation Safety

Volcanic Ash and Aviation Safety: Proceedings of the First International Symposium on Volcanic Ash and Aviation Safety Edited by Thomas J. Casadevall U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY BULLETIN 2047 Proceedings of the First International Symposium on Volcanic Ash and Aviation Safety held in Seattle, Washington, in July I991 @mposium sponsored by Air Line Pilots Association Air Transport Association of America Federal Aviation Administmtion National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration U.S. Geological Survey amposium co-sponsored by Aerospace Industries Association of America American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics Flight Safety Foundation International Association of Volcanology and Chemistry of the Earth's Interior National Transportation Safety Board UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE, WASHINGTON: 1994 U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR BRUCE BABBITT, Secretary U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Gordon P. Eaton, Director For sale by U.S. Geological Survey, Map Distribution Box 25286, MS 306, Federal Center Denver, CO 80225 Any use of trade, product, or firm names in this publication is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S.Government Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data International Symposium on Volcanic Ash and Aviation Safety (1st : 1991 Seattle, Wash.) Volcanic ash and aviation safety : proceedings of the First International Symposium on Volcanic Ash and Aviation Safety I edited by Thomas J. Casadevall ; symposium sponsored by Air Line Pilots Association ... [et al.], co-sponsored by Aerospace Indus- tries Association of America ... [et al.]. p. cm.--(US. Geological Survey bulletin ; 2047) "Proceedings of the First International Symposium on Volcanic Ash and Aviation Safety held in Seattle, Washington, in July 1991." Includes bibliographical references. -

(2000), Voluminous Lava-Like Precursor to a Major Ash-Flow

Journal of Volcanology and Geothermal Research 98 (2000) 153–171 www.elsevier.nl/locate/jvolgeores Voluminous lava-like precursor to a major ash-flow tuff: low-column pyroclastic eruption of the Pagosa Peak Dacite, San Juan volcanic field, Colorado O. Bachmanna,*, M.A. Dungana, P.W. Lipmanb aSection des Sciences de la Terre de l’Universite´ de Gene`ve, 13, Rue des Maraıˆchers, 1211 Geneva 4, Switzerland bUS Geological Survey, 345 Middlefield Rd, Menlo Park, CA, USA Received 26 May 1999; received in revised form 8 November 1999; accepted 8 November 1999 Abstract The Pagosa Peak Dacite is an unusual pyroclastic deposit that immediately predated eruption of the enormous Fish Canyon Tuff (ϳ5000 km3) from the La Garita caldera at 28 Ma. The Pagosa Peak Dacite is thick (to 1 km), voluminous (Ͼ200 km3), and has a high aspect ratio (1:50) similar to those of silicic lava flows. It contains a high proportion (40–60%) of juvenile clasts (to 3–4 m) emplaced as viscous magma that was less vesiculated than typical pumice. Accidental lithic fragments are absent above the basal 5–10% of the unit. Thick densely welded proximal deposits flowed rheomorphically due to gravitational spreading, despite the very high viscosity of the crystal-rich magma, resulting in a macroscopic appearance similar to flow- layered silicic lava. Although it is a separate depositional unit, the Pagosa Peak Dacite is indistinguishable from the overlying Fish Canyon Tuff in bulk-rock chemistry, phenocryst compositions, and 40Ar/39Ar age. The unusual characteristics of this deposit are interpreted as consequences of eruption by low-column pyroclastic fountaining and lateral transport as dense, poorly inflated pyroclastic flows. -

Late Holocene Earthquake History of the Imperial and Brawley Faults, Imperial Valley, California

Late Holocene Earthquake History of the Imperial and Brawley Faults, Imperial Valley, California Aron J. Meltzner and Thomas K. Rockwell Geological Sciences San Diego State University Final Technical Report U.S. Geological Survey Grant No. 02HQGR0008 February, 2004 Table of Contents List of Figures ii Abstract 1 Introduction 4 The Imperial Fault at Harris Road 10 Methodology 14 Trench Stratigraphy 15 Structure and Earthquake History 23 Event Z 23 Event X 23 Event V 24 Event T 24 Discussion 27 Conclusions 30 Acknowledgements 31 References Cited 32 Table 1a and 1b 35 Table 2 36 i LIST OF FIGURES Figure 1. Generalized fault map of the southern part of the Salton Trough. Surface ruptures indicated for the 1892 (M 71/4), 1934 (ML 7.1), 1940 (MW 6.9), 1968 (MW 6.5), 1979 (MW 6.4), and 1987 (MW 6.2 and 6.6) earthquakes. Figure 2. (a) Profiles of right-lateral component of displacement as a function of length along fault for the 1940 and 1979 ruptures. Comparison of slip in the two events shows important similarities and differences. Sieh (1996) argued that this example supports the concept of characteristic slip within individual patches of a fault, but not characteristic earthquakes. He argued that the sharp slip gradients in both 1940 and 1979 a few kilometers north of the international border suggest the presence of a fixed patch boundary. Redrafted from Sharp (1982b). (b) Diagram illustrating the “slip-patch” model as proposed by Sieh (1996) for the Imperial fault: accumulated over scores of earthquake cycles, slip along the fault between stepovers is uniform, and in both stepover regions, slip tapers to zero. -

Explosive Eruptions

Explosive Eruptions -What are considered explosive eruptions? Fire Fountains, Splatter, Eruption Columns, Pyroclastic Flows. Tephra – Any fragment of volcanic rock emitted during an eruption. Ash/Dust (Small) – Small particles of volcanic glass. Lapilli/Cinders (Medium) – Medium sized rocks formed from solidified lava. – Basaltic Cinders (Reticulite(rare) + Scoria) – Volcanic Glass that solidified around gas bubbles. – Accretionary Lapilli – Balls of ash – Intermediate/Felsic Cinders (Pumice) – Low density solidified ‘froth’, floats on water. Blocks (large) – Pre-existing rock blown apart by eruption. Bombs (large) – Solidified in air, before hitting ground Fire Fountaining – Gas-rich lava splatters, and then flows down slope. – Produces Cinder Cones + Splatter Cones – Cinder Cone – Often composed of scoria, and horseshoe shaped. – Splatter Cone – Lava less gassy, shape reflects that formed by splatter. Hydrovolcanic – Erupting underwater (Ocean or Ground) near the surface, causes violent eruption. Marr – Depression caused by steam eruption with little magma material. Tuff Ring – Type of Marr with tephra around depression. Intermediate Magmas/Lavas Stratovolcanoes/Composite Cone – 1-3 eruption types (A single eruption may include any or all 3) 1. Eruption Column – Ash cloud rises into the atmosphere. 2. Pyroclastic Flows Direct Blast + Landsides Ash Cloud – Once it reaches neutral buoyancy level, characteristic ‘umbrella cap’ forms, & debris fall. Larger ash is deposited closer to the volcano, fine particles are carried further. Pyroclastic Flow – Mixture of hot gas and ash to dense to rise (moves very quickly). – Dense flows restricted to valley bottoms, less dense flows may rise over ridges. Steam Eruptions – Small (relative) steam eruptions may occur up to a year before major eruption event. . -

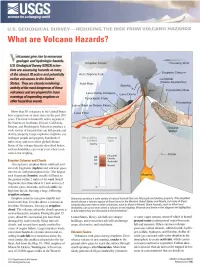

What Are Volcano Hazards?

USGS science for a changing world U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY REDUCING THE RISK FROM VOLCANO HAZARDS What are Volcano Hazards? \7olcanoes give rise to numerous T geologic and hydrologic hazards. Eruption Cloud Prevailing Wind U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) scien tists are assessing hazards at many Eruption Column of the almost 70 active and potentially Ash (Tephra) Fall active volcanoes in the United Landslide (Debris Avalanche) States. They are closely monitoring Acid Rain Bombs activity at the most dangerous of these Pyroclastic Flow volcanoes and are prepared to issue Lava Dome Collapse x Lava Dome warnings of impending eruptions or Pyroclastic Flow other hazardous events. Lahar (Mud or Debris Flow)jX More than 50 volcanoes in the United States Lava Flow have erupted one or more times in the past 200 years. The most volcanically active regions of the Nation are in Alaska, Hawaii, California, Oregon, and Washington. Volcanoes produce a wide variety of hazards that can kill people and destroy property. Large explosive eruptions can endanger people and property hundreds of miles away and even affect global climate. Some of the volcano hazards described below, such as landslides, can occur even when a vol cano is not erupting. Eruption Columns and Clouds An explosive eruption blasts solid and mol ten rock fragments (tephra) and volcanic gases into the air with tremendous force. The largest rock fragments (bombs) usually fall back to the ground within 2 miles of the vent. Small fragments (less than about 0.1 inch across) of volcanic glass, minerals, and rock (ash) rise high into the air, forming a huge, billowing eruption column. -

Explosive Caldera-Forming Eruptions and Debris-Filled Vents: Gargle Dynamics Greg A

https://doi.org/10.1130/G48995.1 Manuscript received 26 February 2021 Revised manuscript received 15 April 2021 Manuscript accepted 20 April 2021 © 2021 The Authors. Gold Open Access: This paper is published under the terms of the CC-BY license. Explosive caldera-forming eruptions and debris-filled vents: Gargle dynamics Greg A. Valentine* and Meredith A. Cole Department of Geology, University at Buffalo, 126 Cooke Hall, Buffalo, New York 14260, USA ABSTRACT conservation equations solved for both gas and Large explosive volcanic eruptions are commonly associated with caldera subsidence and particles, which are coupled through momentum ignimbrites deposited by pyroclastic currents. Volumes and thicknesses of intracaldera and (drag) and heat exchange (as in Sweeney and outflow ignimbrites at 76 explosive calderas around the world indicate that subsidence is com- Valentine, 2017; Valentine and Sweeney, 2018). monly simultaneous with eruption, such that large proportions of the pyroclastic currents The same approach was used to study discrete are trapped within the developing basins. As a result, much of an eruption must penetrate phreatomagmatic explosions in debris-filled its own deposits, a process that also occurs in large, debris-filled vent structures even in the vents (Sweeney and Valentine, 2015; Sweeney absence of caldera formation and that has been termed “gargling eruption.” Numerical et al., 2018), but here we focus on sustained dis- modeling of the resulting dynamics shows that the interaction of preexisting deposits (fill) charges. The simplified two-dimensional (2-D), with an erupting (juvenile) mixture causes a dense sheath of fill material to be lifted along axisymmetric model domain extends to an alti- the margins of the erupting jet. -

Eruptive Proceses Responsible for Fall Tephra in the Upper Miocene Peralta Tuff, Jemez Mountains, New Mexico Sharon Kundel and Gary A

New Mexico Geological Society Downloaded from: http://nmgs.nmt.edu/publications/guidebooks/58 Eruptive proceses responsible for fall tephra in the Upper Miocene Peralta Tuff, Jemez Mountains, New Mexico Sharon Kundel and Gary A. Smith, 2007, pp. 268-274 in: Geology of the Jemez Region II, Kues, Barry S., Kelley, Shari A., Lueth, Virgil W.; [eds.], New Mexico Geological Society 58th Annual Fall Field Conference Guidebook, 499 p. This is one of many related papers that were included in the 2007 NMGS Fall Field Conference Guidebook. Annual NMGS Fall Field Conference Guidebooks Every fall since 1950, the New Mexico Geological Society (NMGS) has held an annual Fall Field Conference that explores some region of New Mexico (or surrounding states). Always well attended, these conferences provide a guidebook to participants. Besides detailed road logs, the guidebooks contain many well written, edited, and peer-reviewed geoscience papers. These books have set the national standard for geologic guidebooks and are an essential geologic reference for anyone working in or around New Mexico. Free Downloads NMGS has decided to make peer-reviewed papers from our Fall Field Conference guidebooks available for free download. Non-members will have access to guidebook papers two years after publication. Members have access to all papers. This is in keeping with our mission of promoting interest, research, and cooperation regarding geology in New Mexico. However, guidebook sales represent a significant proportion of our operating budget. Therefore, only research papers are available for download. Road logs, mini-papers, maps, stratigraphic charts, and other selected content are available only in the printed guidebooks. -

Geological Society of America Bulletin

Downloaded from gsabulletin.gsapubs.org on January 15, 2014 Geological Society of America Bulletin Oceanic magmatism in sedimentary basins of the northern Gulf of California rift Axel K. Schmitt, Arturo Martín, Bodo Weber, Daniel F. Stockli, Haibo Zou and Chuan-Chou Shen Geological Society of America Bulletin 2013;125, no. 11-12;1833-1850 doi: 10.1130/B30787.1 Email alerting services click www.gsapubs.org/cgi/alerts to receive free e-mail alerts when new articles cite this article Subscribe click www.gsapubs.org/subscriptions/ to subscribe to Geological Society of America Bulletin Permission request click http://www.geosociety.org/pubs/copyrt.htm#gsa to contact GSA Copyright not claimed on content prepared wholly by U.S. government employees within scope of their employment. Individual scientists are hereby granted permission, without fees or further requests to GSA, to use a single figure, a single table, and/or a brief paragraph of text in subsequent works and to make unlimited copies of items in GSA's journals for noncommercial use in classrooms to further education and science. This file may not be posted to any Web site, but authors may post the abstracts only of their articles on their own or their organization's Web site providing the posting includes a reference to the article's full citation. GSA provides this and other forums for the presentation of diverse opinions and positions by scientists worldwide, regardless of their race, citizenship, gender, religion, or political viewpoint. Opinions presented in this publication do not reflect official positions of the Society. Notes © 2013 Geological Society of America Downloaded from gsabulletin.gsapubs.org on January 15, 2014 Oceanic magmatism in sedimentary basins of the northern Gulf of California rift Axel K. -

Assessing Eruption Column Height in Ancient Flood Basalt Eruptions

This is a repository copy of Assessing eruption column height in ancient flood basalt eruptions. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/109782/ Version: Accepted Version Article: Glaze, LS, Self, S, Schmidt, A orcid.org/0000-0001-8759-2843 et al. (1 more author) (2017) Assessing eruption column height in ancient flood basalt eruptions. Earth and Planetary Science Letters, 457. pp. 263-270. ISSN 0012-821X https://doi.org/10.1016/j.epsl.2014.07.043 © 2016 Elsevier B.V. and United States Government as represented by the Administrator of the National Aeronautics and Space Administration. Published by Elsevier B.V. This manuscript version is made available under the CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 license http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ Reuse Unless indicated otherwise, fulltext items are protected by copyright with all rights reserved. The copyright exception in section 29 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 allows the making of a single copy solely for the purpose of non-commercial research or private study within the limits of fair dealing. The publisher or other rights-holder may allow further reproduction and re-use of this version - refer to the White Rose Research Online record for this item. Where records identify the publisher as the copyright holder, users can verify any specific terms of use on the publisher’s website. Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. -

Modeling of Pyroclastic Flows of Colima Volcano, Mexico: Implications for Hazard Assessment

Journal of Volcanology and Geothermal Research 139 (2005) 103–115 www.elsevier.com/locate/jvolgeores Modeling of pyroclastic flows of Colima Volcano, Mexico: implications for hazard assessment R. Saucedoa,*, J.L. Macı´asb, M.F. Sheridanc, M.I. Bursikc, J.C. Komorowskid aInstituto de Geologı´a /Fac. Ingenierı´a UASLP, Dr. M. Nava No 5, Zona Universitaria, 78240 San Luis Potosı´, Mexico bInstituto de Geofı´sica, UNAM, Coyoaca´n 04510, D.F., Me´xico cGeology Department, SUNY at Buffalo, Buffalo, NY 14260, USA dInstitut de Physique du Globe de Paris, Paris, Cedex 05, France Accepted 29 June 2004 Abstract The 18–24 January 1913 eruption of Colima Volcano consisted of three eruptive phases that produced a complex sequence of tephra fall, pyroclastic surges and pyroclastic flows, with a total volume of 1.1 km3 (0.31 km3 DRE). Among these events, the pyroclastic flows are most interesting because their generation mechanisms changed with time. They started with gravitanional dome collapse (block-and-ash flow deposits, Merapi-type), changed to dome collapse triggered by a Vulcanian explosion (block-and-ash flow deposits, Soufrie`re-type), then ended with the partial collapse of a Plinian column (ash-flow deposits rich in pumice or scoria,). The best exposures of these deposits occur in the southern gullies of the volcano where Heim Coefficients (H/L) were obtained for the various types of flows. Average H/ L values of these deposits varied from 0.40 for the Merapi-type (similar to the block-and-ash flow deposits produced during the 1991 and 1994 eruptions), 0.26 for the Soufrie`re-type events, and 0.17–0.26 for the column collapse ash flows. -

Super Eruptions.Pdf

Aberystwyth University Super-eruptions Rymer, Hazel; Sparks, Stephen; Self, Stephen; Grattan, John; Oppenheimer, Clive; Pyle, David Publication date: 2005 Citation for published version (APA): Rymer, H., Sparks, S., Self, S., Grattan, J., Oppenheimer, C., & Pyle, D. (2005). Super-eruptions: Global effects and future threats. Geological Society of London. http://hdl.handle.net/2160/197 General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the Aberystwyth Research Portal (the Institutional Repository) are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the Aberystwyth Research Portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the Aberystwyth Research Portal Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. tel: +44 1970 62 2400 email: [email protected] Download date: 10. Oct. 2021 The Jemez Mountains (Valles Caldera) super-volcano, New Mexico, USA. Many super-eruptions have come from volcanoes that are either hard to locate or not very widely known. An example is the Valles Caldera in the Jemez Mountains, near to Santa Fe and Los Alamos, New Mexico, USA. The caldera is the circular feature (centre) in this false-colour (red=vegetation) Landsat image, which shows an area about 80 kilometres across of the region in North-Central New Mexico.