The Subprime and the Beautiful

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Ideal Solution for Schools and Nurseries

The ideal solution for schools and nurseries. Dear customers, Be inspired by tasty recipe ideas. The SelfCookingCenter® offers countless possibilities for producing dishes. This cookbook presents a selection of elegant base recipes put together by the RATIONAL chefs for you to try. You will certainly find a few new ideas for your menu plan. Are you interested in other national and international recipes, tips and tricks? Then visit our Club RATIONAL – our Internet platform for all SelfCookingCenter® users. You will find interesting information and suggestions for your kitchen on the site. Simply log in at www.clubrational.com. We hope you enjoy your new SelfCookingCenter® and we look forward to staying in contact with you. Your RATIONAL chefs 02 04 Roasted, BBQ chicken drumsticks 06 Fried rice 38 Chef Louie's ratatouille 08 Fries, wedges & croquettes 40 Cheese ravioli 10 Scrambled eggs 42 Macaroni & cheese 12 Kale chips 45 Whole grain pasta with tomato & 14 Grilled cheese sandwich basil 16 Italian turkey meatballs 47 Savory roasted pumpkin or butternut squash 18 Cinnamon-raisin bread pudding 49 BBQ pulled pork 21 Corn crusted cod (or catfish) 51 Ground Beef cooked overnight 23 Dehydrated fruits & vegetables 53 Steamed rice 25 Steamed yummy broccoli 55 Alphabet Soup Meatloaf 27 Roasted turkey 57 Roasted pork loin with apples 29 Beef jerky, made in-house 60 Braised brisket with apricot (sub 31 Kid-friendly kale salad pork shoulder) 34 Easy & eggceptional egg 62 Maple Sweet Potato Mash sandwiches 36 Western omelette frittata with cheese 03 Roasted, BBQ chicken drumsticks List of ingredients (Number of portions: 90) 90 pieces of chicken legs 8 oz. -

RATIONAL Serviceplus. Always There for You. Serviceplus

RATIONAL ServicePlus. Always there for you. ServicePlus. Questions are answered before they are even asked. New cooking system, new employees and new ideas. Support, help, service There is always a reason to try out our RATIONAL services Relax and enjoy your that come with every iCombi and iVario unit. RATIONAL day in the kitchen. ServicePlus ensures that you always get the most from you cooking systems, that your investment pays off and that you never run out of ideas. 2 3 First things first. Installation and unit introduction training. Delivery, assembly and installation - it is always best to Individual support invest in the professional support of a RATIONAL Certified To enable you to start easily Service Partner. RATIONAL’s Certified Partners are achieving your goals from regularly trained and are familiar with the latest technology maximizing your uptime. While RATIONAL cooking the very first day. systems are self-explanatory, a couple of tips and tricks can sometimes help. RATIONAL Certified Service Partners are here to help. 4 5 ChefLine. Your direct line to RATIONAL. Here for you 365 days a year: RATIONAL ChefLine. Just call us Questions on preparation methods, settings and cooking and we'll turn your challenges paths, or even on planning a banquet? RATIONAL chefs into solutions. are only a telephone call away. It's their pleasure to provide advice on how to get the most from your cooking system. Fast, uncomplicated and free of charge. Reach the ChefLine at: 866-306-CHEF (2433) 6 7 Always up-to-date. Free updates. The RATIONAL cooking systems continue to progress. -

The Perfect Cooking System for the Hotel Industry. Ideas That Change the World

The perfect cooking system for the hotel industry. Ideas that change the world. For more than forty years now, we have had one goal: to offer you the best and most powerful cooking equipment possible. A tool that offers you a wealth of new options for making your ideas a reality. One that ensures consistent superior quality, no matter how much and what you are preparing. And one that pays for itself in no time. 2 3 Unparalleled quality. Easily and efficiently. Successful hotel gastronomy The goal: thoroughly satisfied concepts feature a wide variety customers who look forward to of top food quality, fast service, and returning and will recommend the efficient processes. Whether large- establishment to others. For them, or small-scale, events in particular it’s all about enjoyment. For you, require that creatively plated meals, it’s about producing excellent food with the same consistent superior easily and efficiently. But how do quality, reach the table quickly. you bring all of those things together? The new RATIONAL SelfCookingCenter® prepares food measurably faster and to the perfect degree of doneness, while yielding more flavorful results. Easy, safe controls ensure that the results are always perfect – no matter who’s operating the appliances and what quantities you’re producing. And you’ll also save dramatically on time, energy, water, and raw materials. 4 5 4 Fits into any kitchen. Grilling, roasting, baking, steaming – all with a single appliance. In the past, preparing a good meal You can use it to grill, roast, bake, steam, stew, poach, and much Our SelfCookingCenter® is now also available in required a wide range of special more, on roughly 11 ft2 (1 m2). -

Luxury Low Countries

LUXURY LUXURY in the LOW LUXURY COUNTRIES the in in the e superflu, chose très nécessaire”, wrote Voltaire 1736 in COUNTRIES LOW LOW his poem Le mondain. Needless to say that luxury is much Lmore than merely materialised/solidified redundancy. Offering a first panoramic view on various manifestations of conspicuous material culture in a Netherlandish context from 1500 until the present, this study – rather than investigating self- COUNTRIES evident cases of luxury – aims to explore its boundaries and the different stages in which luxury is fabricated or sometimes only simulated. Thematically, the volume focuses on two major issues, i.e. collections and foodways as means of expression of prosperity and splendour, which will be discussed by an international group of scholars, emanating from disciplines such as archaeology, history, book and media studies, art history, linguistics, and historical (ed.) Rittersma Rengenier ethnology. With an afterword by Maxine Berg. MIScellaneous RefleCtions on NETHERlandish MaTERial CULTURE, 1500 to the PRESENT Rengenier Rittersma (ed.) www.vubpress.be 9 789054 875406 Miscellaneous Reflections on Netherlandish Material Culture, 1500 to the Present Rengenier C. Rittersma (ed.) © 2010 FARO. Flemish interface for cultural heritage Cover image: Adriaan de Lelie, De kunstgalerij van Jan Priemstraat 51, B-1000 Brussels Gildemeester Jansz in zijn huis aan de Herengracht te www.faronet.be Amsterdam, 1794-1795 www.pharopublishing.be © Rijksmuseum Amsterdam Editorial board: Marc Jacobs, Rengenier C. Rittersma, All rights reserved. No part of this book may be Peter Scholliers, Ans Van de Cotte reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, Final editors: Frederik Hautain & Ans Van de Cotte recording, or on any information, storage or retrieval system without permission of the publisher. -

Case 16-11179 Doc 1 Filed 05/20/16 Entered 05/20/16 17:25:50

Case 16-11179 Doc 1 Filed 05/20/16 Entered 05/20/16 17:25:50 Main Document Page 1 of 17 Case 16-11179 Doc 1 Filed 05/20/16 Entered 05/20/16 17:25:50 Main Document Page 2 of 17 Case 16-11179 Doc 1 Filed 05/20/16 Entered 05/20/16 17:25:50 Main Document Page 3 of 17 Case 16-11179 Doc 1 Filed 05/20/16 Entered 05/20/16 17:25:50 Main Document Page 4 of 17 Case 16-11179 Doc 1 Filed 05/20/16 Entered 05/20/16 17:25:50 Main Document Page 5 of 17 Case 16-11179 Doc 1 Filed 05/20/16 Entered 05/20/16 17:25:50 Main Document Page 6 of 17 Case 16-11179 Doc 1 Filed 05/20/16 Entered 05/20/16 17:25:50 Main Document Page 7 of 17 Case 16-11179 Doc 1 Filed 05/20/16 Entered 05/20/16 17:25:50 Main Document Page 8 of 17 Case 16-11179 Doc 1 Filed 05/20/16 Entered 05/20/16 17:25:50 Main Document Page 9 of 17 Case 16-11179 Doc 1 Filed 05/20/16 Entered 05/20/16 17:25:50 Main Document Page 10 of 17 Case 16-11179 Doc 1 Filed 05/20/16 Entered 05/20/16 17:25:50 Main Document Page 11 of 17 Case 16-11179 Doc 1 Filed 05/20/16 Entered 05/20/16 17:25:50 Main Document Page 12 of 17 Case 16-11179 Doc 1 Filed 05/20/16 Entered 05/20/16 17:25:50 Main Document Page 13 of 17 Case 16-11179 Doc 1 Filed 05/20/16 Entered 05/20/16 17:25:50 Main Document Page 14 of 17 Case 16-11179 Doc 1 Filed 05/20/16 Entered 05/20/16 17:25:50 Main Document Page 15 of 17 Case 16-11179 Doc 1 Filed 05/20/16 Entered 05/20/16 17:25:50 Main Document Page 16 of 17 Case 16-11179 Doc 1 Filed 05/20/16 Entered 05/20/16 17:25:50 Main Document Page 17 of 17 Case 16-11179 Doc 1-1 Filed 05/20/16 Entered 05/20/16 17:25:50 -

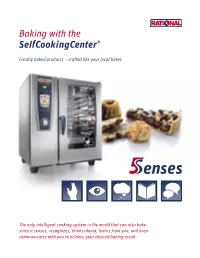

Baking with The

Baking with the Freshly baked products – crafted like your local baker. The only intelligent cooking system in the world that can also bake since it senses, recognizes, thinks ahead, learns from you, and even communicates with you to achieve your desired baking result. 2 | SelfCookingCenter® 5 Senses Baking like a professional. Always fresh. Superior results. Whether sweet or savory baked goods, small or large, With the SelfCookingCenter® 5 Senses, you can prepare fresh or frozen, raw or semi-baked products, your almost all baked goods from around the world. SelfCookingCenter® 5 Senses is equipped with all of the main functions, so that your baked goods will look Your new baking assistant will even consider local and taste like they have just come from the bakery. cooking preferences. Whether you want to bake a golden or chocolate brown succulent cheesecake Everyone can be a baking professional or a creamy New York cheesecake, you are in control ® now. and your SelfCookingCenter 5 Senses will help you. All you have to do is set your desired baking result. Your baking assistant with professional According to which dough you are preparing and technology built-in: whether you want light or dark browning, the SelfCookingCenter® 5 Senses will precisely adjust > Precise amount of steam injection, variable steaming the humidity, temperature, air speed, and baking quantities, and proofing times adjusted to the product time to your specifications. requirements. > Humidity regulation and dynamic air mixing down to the percent for uniform results on every single rack. > Perfect baking with core temperature probes that intelligently adjust to the baking process in accordance with different shapes and sizes. -

Limited Service Hotels. Intelligent Concepts. Higher Revenues. the Day-To-Day Challenge

Limited Service Hotels. Intelligent concepts. Higher revenues. The day-to-day challenge. Impressing your guests. You already know that location and service are important to your guests. That the price-performance ratio has to be right. That you’re operating in an attractive and competitive market. And that is exactly why you need to stand out from the competition. This is something a compelling F&B concept can help you do. Even if you’re under-staffed, short on kitchen space, and don’t have much freedom to experiment. Make your vision a reality Planning and implementing your future concept? No time like the present. 2 3 Just the way you want it. Concept and planning. Trends, ideas, customer preferences - RATIONAL’s concepts reflect them all. And we tailor them specifically to your most pressing concerns. Whether you want help in every area or just one. “Now, on the early shift, just two people can prepare breakfast for 300 guests.” Jens Hulek, Head of Food and Beverage, Premier Inn, Germany Food concept Kitchen concept Training concept Service concept Future concept Aligned to your guests, your The menu, the staff, the size of Tailored to the needs of your RATIONAL works with certified Top today, a flop tomorrow. To overall culinary concept, and your the kitchen– so many factors can workforce. service partners around the world make sure that doesn’t happen, competitive environment: influence your kitchen concept. For that will support you with individual count on regular feedback. one hotel or 100. › How are kitchen employees concepts. -

The Ideal Cooking System for K-12 Schools. Ideas Change the World

The ideal cooking system for K-12 schools. Ideas change the world. We have dedicated over 40 years to achieving one goal – providing you with the best tool for cooking. For you, this means that you always produce the best quality with maximum efficiency using RATIONAL technology. At the end of the day, the children are eating nutritious meals that they will line up for again and again. 2 3 Healthy quality, that makes complete economic sense. Healthy, delicious, and high-quality food for children and young people are hot topics among K-12 school foodservice operations. Health-conscious parents and guardians, increasingly stringent rules and regulations, as well as budget restraints, are challenges that must be overcome daily. In addition, there may be temporary or part-time staff working in the kitchen. There are solutions that work in practice – whether it is for 30, 150, or even more meals. With the RATIONAL SelfCookingCenter®, it is very easy to prepare delicious and diverse foods at the push of a button. You will also benefit in terms of food cost, labor, and energy and water consumption. You can offer healthy dishes that are very tasty, nutritious, and that fit within the budget. 4 5 The SelfCookingCenter®. Unbelievable versatility in a single appliance. With only one SelfCookingCenter®, you can prepare a variety of different foods on roughly 11 ft2 (1 m2) of space. Regardless of whether you are cooking from scratch or simply heating convenience products using Finishing®, the SelfCookingCenter® is always the right solution. It cooks quickly, is easy to use, and provides consistent food quality you want – time and time again. -

A Correlation of the Roman Canon and the Fourfold Sense of Scripture

Marquette University e-Publications@Marquette Dissertations, Theses, and Professional Dissertations (1934 -) Projects Lex Orandi, Lex Legendi: A Correlation of the Roman Canon and the Fourfold Sense of Scripture Matthew Thomas Gerlach Marquette University Follow this and additional works at: https://epublications.marquette.edu/dissertations_mu Part of the Religion Commons Recommended Citation Gerlach, Matthew Thomas, "Lex Orandi, Lex Legendi: A Correlation of the Roman Canon and the Fourfold Sense of Scripture" (2011). Dissertations (1934 -). 122. https://epublications.marquette.edu/dissertations_mu/122 LEX ORANDI, LEX LEGENDI : A CORRELATION OF THE ROMAN CANON AND THE FOURFOLD SENSE OF SCRIPTURE by Matthew T. Gerlach, B.A., M.A.T. A Dissertation submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School, Marquette University, in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Milwaukee, Wisconsin May 2011 ABSTRACT LEX ORANDI , LEX LEGENDI : A CORRELATION OF THE ROMAN CANON AND THE FOURFOLD SENSE OF SCRIPTURE Matthew T. Gerlach, B.A., M.A.T. Marquette University, 2011 While the correlation between the liturgy and the Bible was vital in the patristic- medieval period, a dichotomy grew up between them in modern times. Starting with the assumption that a fuller retrieval of the correlation today requires forms of engaging texts which are not exclusively linear or historico-critical, the dissertation argues that the dichotomy between liturgy and Bible is overcome within a correlation of the Eucharist and spiritual exegesis that retrieves a typological reading of Scripture and that attends to the liturgical relationships memorial, presence, and anticipation. The structure of reading the Bible parallels the structure of praying within the liturgy. -

A Guide for Family Home Providers

illinois CHILD CARE a guide for family home providers Illinois Department of Human Services USDA Rural Development – Illinois Child Care Resource Service – University of Illinois Illinois Network of Child Care Resource and Referral Agencies an IDHS - INCCRRA project Acknowledgments This publication outlines the steps necessary for starting a child care business in your home, and includes a variety of agency and organiza- tional contacts who can provide assistance throughout this process. Illinois Child Care: A Family Home Provider Guide is part of the Illinois Child Care series. It was funded by the Illinois Department of Human Services and produced under the guidance of USDA Rural Development-Illinois and Child Care Resource Service at the Univer- sity of Illinois by Anna Barnes Communications. Additional assis- tance was provided by the members of the Illinois Child Care Task Force: Central Illinois Economic Development Corporation Illinois Chamber of Commerce Illinois Department of Children and Family Services Illinois Department of Commerce and Community Affairs Illinois Network of Child Care Resource and Referral Agencies Illinois Office of the State Treasurer Illinois Easter Seals Society Inclusive Environments Inc. Nutrition For Children, Inc. Rural Partners University of Illinois Extension Special thanks to Lesia Oesterreich and Iowa State University Extension for permission to use Child Care: Financial Basics (PM-1751) as a template for a portion of this publication. Other publications in the Illinois Child Care series include: Illinois Child Care: Developing Center-Based Programs Illinois Child Care: Developing Community Programs Illinois Child Care: Options for Employers To obtain printed copies of these publications, call your local Child Care Resource and Referral Agency. -

Madera Unified School District. Farm to Fork Cuisine

Madera Unified School District. Farm to fork cuisine. Reinventing lunch at school. Students in the Madera Unified School District enjoy fresh farm to fork breakfasts and lunches made with local ingredients prepared “I welcome staff and directors to daily in kitchens equipped with RATIONAL combi ovens. our kitchens to watch what we Located close to the Sierra Nevada mountains and do and how we do it and let the Yosemite National Park in central California, Madera has ready RATIONAL speak for itself.” access to fresh-farmed ingredients from the nearby San Joaquin Brian Chiarito, Director of Child Nutrition, Madera Unified School District Valley and beyond. On a typical day, the school district prepares and serves between 23,000 and 24,000 student meals; enrollment is approximately 20,000 across 28 schools. Every school makes breakfast and lunch available daily to all enrolled students at no cost via the federal Community Eligibility Provision program. Brian Chiarito, Director of Child Nutrition for the Madera Unified School District, takes an innovative, non-traditional approach that tries to change the reputation of the school lunch. “We want to be different,” he said. “We have to change the mindset and perception. We provide lunch at school, not school lunch.” He’s created a restaurant-style burrito bar that emulates what students see in restaurants. “Kids are much smarter, their palates bigger, so the district tries to market it that way,” he said. His menus include entrees like roast, fresh grilled quarter chickens, pizza made just-in-time, and fresh, not frozen, 100 percent beef patties. -

Mémoires-2019.Pdf

MÉMOIRES DE L’ACADÉMIE DE NÎMES IXe SÉRIE TOME XCIII Année 2019 ACADÉMIE DE NÎMES 16, rue Dorée NÎMES (Gard) 2020 TABLE DES MATIÈRES I – SÉANCE PUBLIQUE DU 3 FÉVRIER 2019 Didier Lauga, préfet du Gard Allocution ................................................................................ 7 Daniel-Jean Valade, au nom de M. Jean-Paul Fournier, sénateur-maire de Nîmes Allocution .............................................................................. 15 Bernard Simon, président sortant Compte rendu des travaux académiques de l’année 2018 ..... 19 Simone Mazauric, président de l’académie Histoires d’Académies ........................................................... 27 Véronique Blanc-Bijon, correspondant À propos de mosaïques de Léda, rencontre entre Nîmes et Arles ................................................................................... 39 II – COMMUNICATIONS DE L’ANNÉE 2019 Jean-Marie Mercier, correspondant Un peintre chez les félibres ou l’adoration d’Auguste Chabaud pour le “Mage de la Provence” .............................................. 69 Michel Belin, vice-président Marcel et Jeanne Encontre, un couple de résistants pendant la guerre 39-45 ......................................................................... 107 Alain Girard, membre non résidant Enfants exposés à Pont-Saint-Esprit .................................... 125 Christian Feller, correspondant Merci M. Darwin (signé Lumbricus terrestris) .................... 143 Claire Torreilles, correspondant Le Vert Paradis de Max Rouquette. Une vie d’écriture