A Correlation of the Roman Canon and the Fourfold Sense of Scripture

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Liturgical Vestments

Saint Mary Magdalen Parish 2005 Berryman Street Berkeley, California 94709 “Together we share our faith in Jesus Christ. We live the Gospel, and we care for others.” DAILY MASS SCHEDULE WELCOME TO OUR COMMUNITY. Monday - Saturday: 8:00 am Monday - Friday: 5:30 pm We are delighted to have all of you here, and we SUNDAY LITURGY hope you will find our Saturday: 5:30 pm Vigil Mass parish a place where Sunday: 8:00, 9:30 & 11:00 am you grow spiritually, LITURGY OF THE HOURS put faith into action, Monday - Friday: 7:30 am & 5:15 pm Saturday: 7:30 am and encounter Jesus Christ. RECONCILIATION Saturdays: 4:00 pm - 5:00 pm Website: www.marymagdalen.org and by appointment PARISH OFFICE HOURS & PHONE NUMBERS Monday-Friday Office Phone (510) 526-4811 9:00 am - 5:00 pm Office Fax (510) 525-3638 Closed for Lunch: 2005 Berryman Street Noon - 1:00 pm Berkeley, CA 94709 Please Pray for the Newest Members of our Church: Neophytes Confirmed at the Easter Vigil Mandi Billinge Heather Bartow Sarah Mills Marcell Vazquez-Chanlatte James Kliegel Grant Nakamura Rose Ellis Parish & School Staff Parish Calendar: April-May 15, 2018 Fr. Nicholas Glisson, Pastor (ext. 112) April 22 4th Sunday Dinner for the Poor [email protected] Sunday 12:00 (set up); 3:00 pm (dinner), Parish Hall Norah Hippolyte, Business Manager April 22 CONCERT: Music Sources Sunday 5:00 pm, Church. ‘Trio Ignacio’ [email protected] (ext. 111) April 24 RCIA/Mystagogy Andy Canepa, Music Director (ext. 122) Tuesdays at 7:00 pm, Norton Hall [email protected] April 25 SPRED [Special Religious Education] Wednesdays at 6:00 pm, Norton Hall Heather Skinner, Director of Religious Education April 26 Faith Studies: Oremus-Catholic Prayer (510) 526-4744 [email protected] Thursdays at 7:00 pm in Norton Hall Dc. -

The Ideal Solution for Schools and Nurseries

The ideal solution for schools and nurseries. Dear customers, Be inspired by tasty recipe ideas. The SelfCookingCenter® offers countless possibilities for producing dishes. This cookbook presents a selection of elegant base recipes put together by the RATIONAL chefs for you to try. You will certainly find a few new ideas for your menu plan. Are you interested in other national and international recipes, tips and tricks? Then visit our Club RATIONAL – our Internet platform for all SelfCookingCenter® users. You will find interesting information and suggestions for your kitchen on the site. Simply log in at www.clubrational.com. We hope you enjoy your new SelfCookingCenter® and we look forward to staying in contact with you. Your RATIONAL chefs 02 04 Roasted, BBQ chicken drumsticks 06 Fried rice 38 Chef Louie's ratatouille 08 Fries, wedges & croquettes 40 Cheese ravioli 10 Scrambled eggs 42 Macaroni & cheese 12 Kale chips 45 Whole grain pasta with tomato & 14 Grilled cheese sandwich basil 16 Italian turkey meatballs 47 Savory roasted pumpkin or butternut squash 18 Cinnamon-raisin bread pudding 49 BBQ pulled pork 21 Corn crusted cod (or catfish) 51 Ground Beef cooked overnight 23 Dehydrated fruits & vegetables 53 Steamed rice 25 Steamed yummy broccoli 55 Alphabet Soup Meatloaf 27 Roasted turkey 57 Roasted pork loin with apples 29 Beef jerky, made in-house 60 Braised brisket with apricot (sub 31 Kid-friendly kale salad pork shoulder) 34 Easy & eggceptional egg 62 Maple Sweet Potato Mash sandwiches 36 Western omelette frittata with cheese 03 Roasted, BBQ chicken drumsticks List of ingredients (Number of portions: 90) 90 pieces of chicken legs 8 oz. -

Epistles of St Paul

NOTES ON EPISTLES OF ST PAUL FROM UNPUBLISHED COMMENT ARIES. ~ • • • NOTES ON EPISTLES OF ST PAUL FROM UNPUBLISHED COMMENTARIES BY THE LATE J. B. LIGHTFOOT, D.D., D.C.L., LL.D., LORD BISHOP OF DURHAM. PUBLISHED BY THE TRUSTEES OF THE LIGHTFOOT FUND. lLonbon: MACMILLAN AND CO. AND NEW YORK. 1895 [All Rights reserved.] i!tambribgc : PRINTED BY J. & C. F. CLAY, AT THE UNIVERSITY PRESS. INTRODUCTORY NOTE. HE present work represents the fulfilment of the under T taking announced in the preface to 'Biblical E~says' a year and a half ago. As that volume consisted of introduc tory essays upon New Testament subjects, so this comprises such of Dr Lightfoot's notes on the text as in the opinion of the Trustees of the Lightfoot Fund are sufficiently complete to justify publication. However, unlike 'Biblical Essays,' of which a considerable part had already been given to the world, this volume, as its title-page indicates, consists entirely of unpublished matter. It aims at reproducing, wherever possible, the courses of lectures delivered at Cambridge by Dr Lightfoot upon those Pauline Epistles which he did not live to edit in the form of complete commentaries. His method of trustiqg to his memory in framing sentences in the lecture room has been alluded to already in the preface to the previous volume. But here again the Editor's difficulty has been considerably lessened by the kindness of friends who were present at the lectures and have placed their note books at the disposal of the Trustees. As on the previous occasion, the thanks of the Trustees are especially due to W. -

RATIONAL Serviceplus. Always There for You. Serviceplus

RATIONAL ServicePlus. Always there for you. ServicePlus. Questions are answered before they are even asked. New cooking system, new employees and new ideas. Support, help, service There is always a reason to try out our RATIONAL services Relax and enjoy your that come with every iCombi and iVario unit. RATIONAL day in the kitchen. ServicePlus ensures that you always get the most from you cooking systems, that your investment pays off and that you never run out of ideas. 2 3 First things first. Installation and unit introduction training. Delivery, assembly and installation - it is always best to Individual support invest in the professional support of a RATIONAL Certified To enable you to start easily Service Partner. RATIONAL’s Certified Partners are achieving your goals from regularly trained and are familiar with the latest technology maximizing your uptime. While RATIONAL cooking the very first day. systems are self-explanatory, a couple of tips and tricks can sometimes help. RATIONAL Certified Service Partners are here to help. 4 5 ChefLine. Your direct line to RATIONAL. Here for you 365 days a year: RATIONAL ChefLine. Just call us Questions on preparation methods, settings and cooking and we'll turn your challenges paths, or even on planning a banquet? RATIONAL chefs into solutions. are only a telephone call away. It's their pleasure to provide advice on how to get the most from your cooking system. Fast, uncomplicated and free of charge. Reach the ChefLine at: 866-306-CHEF (2433) 6 7 Always up-to-date. Free updates. The RATIONAL cooking systems continue to progress. -

The Perfect Cooking System for the Hotel Industry. Ideas That Change the World

The perfect cooking system for the hotel industry. Ideas that change the world. For more than forty years now, we have had one goal: to offer you the best and most powerful cooking equipment possible. A tool that offers you a wealth of new options for making your ideas a reality. One that ensures consistent superior quality, no matter how much and what you are preparing. And one that pays for itself in no time. 2 3 Unparalleled quality. Easily and efficiently. Successful hotel gastronomy The goal: thoroughly satisfied concepts feature a wide variety customers who look forward to of top food quality, fast service, and returning and will recommend the efficient processes. Whether large- establishment to others. For them, or small-scale, events in particular it’s all about enjoyment. For you, require that creatively plated meals, it’s about producing excellent food with the same consistent superior easily and efficiently. But how do quality, reach the table quickly. you bring all of those things together? The new RATIONAL SelfCookingCenter® prepares food measurably faster and to the perfect degree of doneness, while yielding more flavorful results. Easy, safe controls ensure that the results are always perfect – no matter who’s operating the appliances and what quantities you’re producing. And you’ll also save dramatically on time, energy, water, and raw materials. 4 5 4 Fits into any kitchen. Grilling, roasting, baking, steaming – all with a single appliance. In the past, preparing a good meal You can use it to grill, roast, bake, steam, stew, poach, and much Our SelfCookingCenter® is now also available in required a wide range of special more, on roughly 11 ft2 (1 m2). -

Worship Resources During a Pandemic

Worship Resources During a Pandemic Index: BAS- Book of Alternative Services BCP- Book of Common Prayer CWDP- Common Worship Daily Prayer CWPS - Common Worship Pastoral Services CWPMC- Common Worship Pastoral Ministry Companion ACC- Anglican Church of Canada TEC- The Episcopal Church ELPC – Evangelical Lutheran Pastoral Care NZ - New Zealand Prayer Book Anglican Church of Canada Liturgical Resources can be found online here: https://www.anglican.ca/about/liturgicaltexts/ Item Resources Daily prayer - emergency, isolation, website BAS - Morning Prayer p. 47 resources Common Worship Daily Prayer (available online at https://www.churchofengland.org/prayer-and- worship/join-us-daily-prayer) BCP - Morning Prayer p. 4 Celebrating Common praise (Franciscans) Presbyterian Church of Canada https://www.presbycan.ca/ Evening Prayer/Compline - NZ Night Prayer p.167 Prayers for those severely ill or dying BAS Ministry of the Sick p. 556ff BCP p. 57ff See Appendix A for further resources. CWPMC- p.36ff CWPMC- p.65.ff ELPC- p.163ff ELPC- p.201ff Funeral Services CWPS p. 257ff BAS p.565ff ELPC p.201ff NZ p.809ff Avon & Somerset - The Faith Communities’ Major Emergency Plan: A Multi-Faith Response to a Major Emergency or Disaster: Appendix, nov. 2004 ed. TEC Occasional Services p. 156 - Burial of One who did not profess the Christian Faith Diocese of Niagara Devotionals Source URL Canadian Bible Society https://biblesociety.ca/resources/for-you/daily-bible-reading/ Prayer Blog https://oneresurrection.wordpress.com/ Bible Study Online https://www.biblestudytools.com/ -

Luxury Low Countries

LUXURY LUXURY in the LOW LUXURY COUNTRIES the in in the e superflu, chose très nécessaire”, wrote Voltaire 1736 in COUNTRIES LOW LOW his poem Le mondain. Needless to say that luxury is much Lmore than merely materialised/solidified redundancy. Offering a first panoramic view on various manifestations of conspicuous material culture in a Netherlandish context from 1500 until the present, this study – rather than investigating self- COUNTRIES evident cases of luxury – aims to explore its boundaries and the different stages in which luxury is fabricated or sometimes only simulated. Thematically, the volume focuses on two major issues, i.e. collections and foodways as means of expression of prosperity and splendour, which will be discussed by an international group of scholars, emanating from disciplines such as archaeology, history, book and media studies, art history, linguistics, and historical (ed.) Rittersma Rengenier ethnology. With an afterword by Maxine Berg. MIScellaneous RefleCtions on NETHERlandish MaTERial CULTURE, 1500 to the PRESENT Rengenier Rittersma (ed.) www.vubpress.be 9 789054 875406 Miscellaneous Reflections on Netherlandish Material Culture, 1500 to the Present Rengenier C. Rittersma (ed.) © 2010 FARO. Flemish interface for cultural heritage Cover image: Adriaan de Lelie, De kunstgalerij van Jan Priemstraat 51, B-1000 Brussels Gildemeester Jansz in zijn huis aan de Herengracht te www.faronet.be Amsterdam, 1794-1795 www.pharopublishing.be © Rijksmuseum Amsterdam Editorial board: Marc Jacobs, Rengenier C. Rittersma, All rights reserved. No part of this book may be Peter Scholliers, Ans Van de Cotte reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, Final editors: Frederik Hautain & Ans Van de Cotte recording, or on any information, storage or retrieval system without permission of the publisher. -

THE EUCHARIST Lent

Passiontide Passiontide begins with The Fifth Sunday of Lent. These forms are used. Invitation to Confession God shows his l ove for us in that, while we were still sinners, Christ died for us. Let us then show our love for him by confessing our sins i n penitence and faith. Introduction to the Peace Once we were far off, but now in union with Christ Jesus THE we have been broug ht near through the shedding of Christ’s blood, for he is our peace. EUCHARIST Preface It is indeed right and just, Holy Communion our duty and our sal vation, always and everywhere to give you thanks, Common Worship holy Father, almighty and eternal God, through Jesus Christ our Lord. Order One For as t he time of his passion and resurrection draws near the whole world is called to acknowledge his hidden majesty. The power of t he life -giving cross reveals the judgement that has come upon the world and the triumph of Christ crucified. Lent He is the victim w ho dies no more, the Lamb once slain, who lives for ever, our advocate in heaven to plead our cause, exalting us there to join w ith angels and archangels, for ever praising you and saying: Blessing Christ crucified draw you to himself, to find in him a sure ground for faith, a firm support for hope, and the assurance of sins forgiven; and the blessing … Copyright Common Wor ship: Copyright © The Archbishops' Council 2000 This booklet is not for sale, but is produced exclusively for local use by this church: A Labarum Longbook Church to append label or rubber stamp. -

GRAS NOTICE 820, Lactobacillus Fermentum CECT5716

GRAS Notice (GRN) No. 820 https://www.fda.gov/food/generally-recognized-safe-gras/gras-notice-inventory ~ b . ? •~::!~ ... BIOSEARCH •::• LIFE October 23, 2018 Office of Food Additive Safety (HFS-200) Center for Food Safety and Applied Nutrition, Food and Drug Administration 5001 Campus Drive College Park - MD 20740 USA Dear Office of Food Additive Safety, Please accept these documents as submission for Generally Recognized as Safe (GRAS) evaluation of the probiotic, Lactobacillus fermentum CECT57 I 6, according to the Final Rule 21 CFR Parts 20, 25, 170, 184, 186 and 570. Do not hesitate to contact me for further clarification or to request additional i. Thank you for your time. BiOSEARCH, S .A C I F A - 18550111 Camino de Purchil, n° 66 18004 GRANADA OCT 2 6 2018 Laura Macho Valls Regulatory Affairs Manager OFFICE OF Biosearch Life. FOOD ADDITIVE SAFETY IIJOS~ARCH S.A. • Camino de Purcl'lil, 66 • 18004 GRANADA (Spain) • Tlfno: {+34) 958240152 • Fax: (+34) 958240160 • lnfo~ b1osearchlile.com • 28031 Madnd (Spa,n) • Tlrno: (•34) 913 802 973 • Fax: (•34) 913 802 279 • sales(a1biosearchlife.com inscr,ta en el Registro Mercantil de Granada. T. 914, F. 164, seccl6n 8, H GR-17202. Fecha 13-11-2000. • CIF es A-185S0111 blOSHl'Chllle.com GRAS ASSESSMENT Lactobacillus fermentum CECT5716 Version 1 ... •~::~~ BIOSEARCH 1 •••·- LIFE Madrid, 23 rd October 2018. OCT 2 6 2018 OFFICE OF FOOD ADDITIVE SAFETY I .-:~~~ BIOSEARCH •::• LIFE Content Part 1. Signed statements and certification ......................................................... 4 I. I GRAS notice accordi ng to 2 1 CFR § 170.225 ........... .. .. .... ..... .. ............ .. .. .................................... .. ..... ... ..... .. ... .. .4 1.2 ame and address of notifier. -

Case 16-11179 Doc 1 Filed 05/20/16 Entered 05/20/16 17:25:50

Case 16-11179 Doc 1 Filed 05/20/16 Entered 05/20/16 17:25:50 Main Document Page 1 of 17 Case 16-11179 Doc 1 Filed 05/20/16 Entered 05/20/16 17:25:50 Main Document Page 2 of 17 Case 16-11179 Doc 1 Filed 05/20/16 Entered 05/20/16 17:25:50 Main Document Page 3 of 17 Case 16-11179 Doc 1 Filed 05/20/16 Entered 05/20/16 17:25:50 Main Document Page 4 of 17 Case 16-11179 Doc 1 Filed 05/20/16 Entered 05/20/16 17:25:50 Main Document Page 5 of 17 Case 16-11179 Doc 1 Filed 05/20/16 Entered 05/20/16 17:25:50 Main Document Page 6 of 17 Case 16-11179 Doc 1 Filed 05/20/16 Entered 05/20/16 17:25:50 Main Document Page 7 of 17 Case 16-11179 Doc 1 Filed 05/20/16 Entered 05/20/16 17:25:50 Main Document Page 8 of 17 Case 16-11179 Doc 1 Filed 05/20/16 Entered 05/20/16 17:25:50 Main Document Page 9 of 17 Case 16-11179 Doc 1 Filed 05/20/16 Entered 05/20/16 17:25:50 Main Document Page 10 of 17 Case 16-11179 Doc 1 Filed 05/20/16 Entered 05/20/16 17:25:50 Main Document Page 11 of 17 Case 16-11179 Doc 1 Filed 05/20/16 Entered 05/20/16 17:25:50 Main Document Page 12 of 17 Case 16-11179 Doc 1 Filed 05/20/16 Entered 05/20/16 17:25:50 Main Document Page 13 of 17 Case 16-11179 Doc 1 Filed 05/20/16 Entered 05/20/16 17:25:50 Main Document Page 14 of 17 Case 16-11179 Doc 1 Filed 05/20/16 Entered 05/20/16 17:25:50 Main Document Page 15 of 17 Case 16-11179 Doc 1 Filed 05/20/16 Entered 05/20/16 17:25:50 Main Document Page 16 of 17 Case 16-11179 Doc 1 Filed 05/20/16 Entered 05/20/16 17:25:50 Main Document Page 17 of 17 Case 16-11179 Doc 1-1 Filed 05/20/16 Entered 05/20/16 17:25:50 -

Affirmations of Faith Suitable for the Seasons of the Church Year

AFFIRMATIONS OF FAITH SUITABLE FOR THE SEASONS OF THE CHURCH YEAR For Advent and Lent Jesus Christ is Lord (Uniting in Worship People’s Book - page 128) We believe in Christ Jesus, who, though he was in the form of God, did not regard equality with God as something to be exploited, but emptied himself, taking the form of a slave, being born in human likeness. And being found in human form, he humbled himself and became obedient to the point of death – even death on a cross. Therefore God also highly exalted him and gave him the name that is above every name, so that at the name of Jesus every knee should bend, in heaven and on earth and under the earth, and every tongue should confess to the glory of God: Jesus Christ is Lord! Amen. (Philippians 2:5-11) For Easter Let us declare our faith in the resurrection of our Lord Jesus Christ. Christ died for our sins in accordance with the Scriptures; he was buried; he was raised to life on the third day in accordance with the Scriptures; afterwards he appeared to his followers, and to all the apostles: this we have received, and this we believe. Amen. (From I Corinthians 15) (New Patterns for Worship, and throughout Common Worship: http://www.churchofengland.org/prayer- worship/worship/texts/newpatterns/contents/sectione.aspx See also: 1. Christ is Risen (Uniting in Worship People’s Book - page 127) Christ our Passover has been sacrificed for us; therefore let us celebrate the festival, not with the old leaven of malice and evil, but with the unleavened bread of sincerity and truth. -

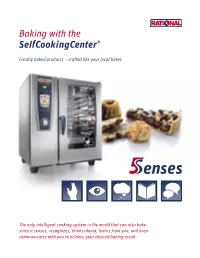

Baking with The

Baking with the Freshly baked products – crafted like your local baker. The only intelligent cooking system in the world that can also bake since it senses, recognizes, thinks ahead, learns from you, and even communicates with you to achieve your desired baking result. 2 | SelfCookingCenter® 5 Senses Baking like a professional. Always fresh. Superior results. Whether sweet or savory baked goods, small or large, With the SelfCookingCenter® 5 Senses, you can prepare fresh or frozen, raw or semi-baked products, your almost all baked goods from around the world. SelfCookingCenter® 5 Senses is equipped with all of the main functions, so that your baked goods will look Your new baking assistant will even consider local and taste like they have just come from the bakery. cooking preferences. Whether you want to bake a golden or chocolate brown succulent cheesecake Everyone can be a baking professional or a creamy New York cheesecake, you are in control ® now. and your SelfCookingCenter 5 Senses will help you. All you have to do is set your desired baking result. Your baking assistant with professional According to which dough you are preparing and technology built-in: whether you want light or dark browning, the SelfCookingCenter® 5 Senses will precisely adjust > Precise amount of steam injection, variable steaming the humidity, temperature, air speed, and baking quantities, and proofing times adjusted to the product time to your specifications. requirements. > Humidity regulation and dynamic air mixing down to the percent for uniform results on every single rack. > Perfect baking with core temperature probes that intelligently adjust to the baking process in accordance with different shapes and sizes.