The Case of Ravi Shankar

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Anoushka Shankar Thursday, May 2, 2019 at 8:00Pm This Is the 939Th Concert in Koerner Hall

Anoushka Shankar Thursday, May 2, 2019 at 8:00pm This is the 939th concert in Koerner Hall Anoushka Shankar, sitar Ojas Adhiya, tabla Pirashanna Thevarajah, mridangam Ravichandra Kulur, flute Danny Keane, cello & piano Kenji Ota, tanpura Anoushka Shankar Sitar player and composer Anoushka Shankar is a singular figure in the Indian classical and progressive world music scenes. Her dynamic and spiritual musicality has garnered several prestigious accolades, including six Grammy Award nominations, recognition as the youngest – and first female – recipient of a British House of Commons Shield, credit as an Asian Hero by TIME magazine, an Eastern Eye Award for Music, and a Songlines Best Artist Award. Most recently, she became one of the first five female composers to have been added to the UK A-level music syllabus. Deeply rooted in the Indian classical music tradition, Shankar studied exclusively from the age of nine under her father and guru, the late Ravi Shankar, and made her professional debut as a classical sitarist at the age of 13. By the age of 20, she had made three classical recordings for EMI/Angel and received her first Grammy nomination, thereby becoming the first Indian female and youngest-ever nominee in the world music category. She is also the first Indian artist to perform at the Grammy Awards. In addition to performing as a solo sitarist, her compositional work has led to cross-cultural collaborations with artists such as Sting, M.I.A., Herbie Hancock, Pepe Habichuela, Karsh Kale, Rodrigo y Gabriela, and Joshua Bell, demonstrating the versatility of the sitar across musical genres. -

Anoushka Shankar: Breathing Under Water – ‘Burn’, ‘Breathing Under Water’ and ‘Easy’ (For Component 3: Appraising)

Anoushka Shankar: Breathing Under Water – ‘Burn’, ‘Breathing Under Water’ and ‘Easy’ (For component 3: Appraising) Background information and performance circumstances The composer Anoushka Shankar was born in 1981, in London, and is the daughter of the famous sitar player Ravi Shankar. She was brought up in London, Delhi and California, where she attended high school. She studied sitar with her father from the age of 7, began playing tampura in his concerts at 10, and gave her first solo sitar performances at 13. She signed her first recording contract at 16 and her first three album releases were of Indian Classical performances. Her first cross-over/fusion album – Rise – was released in 2005 and was nominated for a Grammy, in the Contemporary World Music category. Her albums since Breathing Under Water have continued to explore the connections between Indian music and other styles. She has collaborated with some major artists – Sting, Nithin Sawhney, Joshua Bell and George Harrison, as well as with her father, Ravi Shankar, and her half-sister, Norah Jones. She has also performed around the world as a Classical sitar player – playing her father’s sitar concertos with major orchestras. The piece Breathing Under Water was Anoushka Shankar’s fifth album, and her second of original fusion music. Her main collaborator was Utkarsha (Karsh) Kale, an Indian musician and composer and co-founder of Tabla Beat Science – an Indian band exploring ambient, drum & bass and electronica in a Hindustani music setting. Kale contributes dance music textures and technical expertise, as well as playing tabla, drums and guitar on the album. -

A Novel Hybrid Approach for Retrieval of the Music Information

International Journal of Applied Engineering Research ISSN 0973-4562 Volume 12, Number 24 (2017) pp. 15011-15017 © Research India Publications. http://www.ripublication.com A Novel Hybrid Approach for Retrieval of the Music Information Varsha N. Degaonkar Research Scholar, Department of Electronics and Telecommunication, JSPM’s Rajarshi Shahu College of Engineering, Pune, Savitribai Phule Pune University, Maharashtra, India. Orcid Id: 0000-0002-7048-1626 Anju V. Kulkarni Professor, Department of Electronics and Telecommunication, Dr. D. Y. Patil Institute of Technology, Pimpri, Pune, Savitribai Phule Pune University, Maharashtra, India. Orcid Id: 0000-0002-3160-0450 Abstract like automatic music annotation, music analysis, music synthesis, etc. The performance of existing search engines for retrieval of images is facing challenges resulting in inappropriate noisy Most of the existing human computation systems operate data rather than accurate information searched for. The reason without any machine contribution. With the domain for this being data retrieval methodology is mostly based on knowledge, human computation can give best results if information in text form input by the user. In certain areas, machines are taken in a loop. In recent years, use of smart human computation can give better results than machines. In mobile devices is increased; there is a huge amount of the proposed work, two approaches are presented. In the first multimedia data generated and uploaded to the web every day. approach, Unassisted and Assisted Crowd Sourcing This data, such as music, field sounds, broadcast news, and techniques are implemented to extract attributes for the television shows, contain sounds from a wide variety of classical music, by involving users (players) in the activity. -

Assets.Kpmg › Content › Dam › Kpmg › Pdf › 2012 › 05 › Report-2012.Pdf

Digitization of theatr Digital DawnSmar Tablets tphones Online applications The metamorphosis kingSmar Mobile payments or tphones Digital monetizationbegins Smartphones Digital cable FICCI-KPMG es Indian MeNicdia anhed E nconttertainmentent Tablets Social netw Mobile advertisingTablets HighIndus tdefinitionry Report 2012 E-books Tablets Smartphones Expansion of tier 2 and 3 cities 3D exhibition Digital cable Portals Home Video Pay TV Portals Online applications Social networkingDigitization of theatres Vernacular content Mobile advertising Mobile payments Console gaming Viral Digitization of theatres Tablets Mobile gaming marketing Growing sequels Digital cable Social networking Niche content Digital Rights Management Digital cable Regionalisation Advergaming DTH Mobile gamingSmartphones High definition Advergaming Mobile payments 3D exhibition Digital cable Smartphones Tablets Home Video Expansion of tier 2 and 3 cities Vernacular content Portals Mobile advertising Social networking Mobile advertising Social networking Tablets Digital cable Online applicationsDTH Tablets Growing sequels Micropayment Pay TV Niche content Portals Mobile payments Digital cable Console gaming Digital monetization DigitizationDTH Mobile gaming Smartphones E-books Smartphones Expansion of tier 2 and 3 cities Mobile advertising Mobile gaming Pay TV Digitization of theatres Mobile gamingDTHConsole gaming E-books Mobile advertising RegionalisationTablets Online applications Digital cable E-books Regionalisation Home Video Console gaming Pay TVOnline applications -

Indian EXPRESS TRI-STATE Newsline NOVEMBER 16, 2012 L

20 The Indian EXPRESS TRI-STATE Newsline NOVEMBER 16, 2012 L. Subrmaniam, Kavitha to perform in NY on Dec 9 PRAKASH M SWAMY New York Philharmonic Orchestra in London, The Kennedy Center in and Zubin Mehta’s Fantasy of Ve- Washington DC, The Lincoln Center NEW YORK dic Chants, the Swiss Romande Or- in New York, Madison Square Gar- chestra Turbulence, the Kirov Ballet den, Zhongshan Music hall in Bei- nternationally renowned violin Shanti Priya, the Oslo Philharmonic jing, The Esplanade in Singapore, etc. maestro Padma Bhushan Dr. Orchestra the Concerto for Two Vio- Few of her famous songs are IL. Subramaniam and his wife lins, the Berlin Opera Global Sym- from movies 1942: A love Story, Mr Kavita Krishnamurti Subramaniam, phony. His compositions have been India, Bombay, Hum dil de chuke an accomplished Bollywood play- used in various stage presentations sanam, Dil Chahta Hai, Kabhi back and Hindustani classical music including San Jose Ballet Company Khushi Kabhi Gam. singer, will present a grand concert and Alvin Ailey Company. The event will be held at NYU for South Asian Music and Arts As- Kavita Krishnamurti Subrama- Skirball auditorium in Washington sociation on Dec 9 in New York City. niam is a famous playback singer, Square in New York. India’s violin icon is a child trained in Hindustani classical music According to Simmi Bhatia, prodigy and was given the title Vio- and a winner of Padmashri award. executive director SAMAA (South lin Chakravarthy (emperor of the A versatile singer who has sung with Asian Music and Arts Association) is violin), Grammy nominated, win- Indian classical maestros like Pandit a non-profit organization dedicated ner Dr Subramaniam has scored Jasraj and BalaMurali Krishna, while to promoting quality music and arts for films like Salaam Bombay and also worked with music composers from South Asia through live perfor- Mississippi Masala, featured soloist like R. -

Cover Next Page > Cover Next Page >

cover next page > title: Indian Music and the West : Gerry Farrell author: Farrell, Gerry. publisher: Oxford University Press isbn10 | asin: 0198167172 print isbn13: 9780198167174 ebook isbn13: 9780585163727 language: English subject Music--India--History and criticism, Music--Indic influences, Civilization, Western--Indic influences, Ethnomusicology. publication date: 1999 lcc: ML338.F37 1999eb ddc: 780.954 subject: Music--India--History and criticism, Music--Indic influences, Civilization, Western--Indic influences, Ethnomusicology. cover next page > < previous page page_i next page > Page i Indian Music and the West < previous page page_i next page > < previous page page_ii next page > Page ii To Jane < previous page page_ii next page > < previous page page_iii next page > Page iii Indian Music and the West Gerry Farrell OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS < previous page page_iii next page > < previous page page_iv next page > Page iv OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS Great Clarendon Street, Oxford OX2 6DP Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide in Oxford New York Athens Auckland Bangkok Bogotá Buenos Aires Calcutta Cape Town Chennai Dar es Salaam Delhi Florence Hong Kong Istanbul Karachi Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Mumbai Nairobi Paris São Paulo Singapore Taipei Tokyo Toronto Warsaw and associated companies in Berlin Ibadan Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries Published in the United States by Oxford University Press Inc., New York © Gerry Farrell 1997 First published 1997 New as paperback edition 1999 The moral rights of the author have been asserted Database right Oxford University Press (maker) All rights reserved. -

David Pontbriand and Brian Shankar Adler

music presents David Pontbriand and Brian Shankar Adler Saturday, March 20, 2021 Live-Streamed from the Olin Concert Hall 7:30 pm About the Concert Sitarist David Pontbriand and percussionist/composer Brian Shankar Adler perform an evening of pieces and songs connected (in one way or another) to India. Unusual settings of sitar with vibraphone, drum set, and bomba legüero, engage in textural dialogue with the more customary duo of sitar and tabla. The program includes improvisations, original compositions, and folk songs, as well as works by Ellington/Strayhorn and Lennon/McCartney. Program Introduction Drone (Adler) is inspired by the subtle, hypnotic hum of the tamboura, a plucked string instrument from India. In this piece, I am seeking to create a similarly meditative effect through the use of weaving rhythms that stretch and contract; a palindrome, with no fixed beginning or ending. –BSA Alaap is the name for the exploratory opening section of a raga performance, where the raga theme is gradually unfolded and developed, in free time. In the Indian classical tradition, ragas are melodic frameworks based on one or more modal scales, each with specific conventions of phrasing that suggest a distinct melodic shape, or flavor. Within this framework, the artist creates a unique spontaneous composition with each performance. My alaap is an original conception, for sitar solo, combining melodic elements from two different raga forms with elements of free improvisation, in a “stream of consciousness” series of episodic variations. The vibes provide an atmospheric envelope, gently framing and supporting the melodic variations. –DP Gat is a composition for sitar and tabla, where the themes developed in the alaap are further explored in a rhythmic framework called tala. -

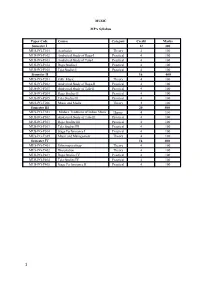

MUSIC MPA Syllabus Paper Code Course Category Credit Marks

MUSIC MPA Syllabus Paper Code Course Category Credit Marks Semester I 12 300 MUS-PG-T101 Aesthetics Theory 4 100 MUS-PG-P102 Analytical Study of Raga-I Practical 4 100 MUS-PG-P103 Analytical Study of Tala-I Practical 4 100 MUS-PG-P104 Raga Studies I Practical 4 100 MUS-PG-P105 Tala Studies I Practical 4 100 Semester II 16 400 MUS-PG-T201 Folk Music Theory 4 100 MUS-PG-P202 Analytical Study of Raga-II Practical 4 100 MUS-PG-P203 Analytical Study of Tala-II Practical 4 100 MUS-PG-P204 Raga Studies II Practical 4 100 MUS-PG-P205 Tala Studies II Practical 4 100 MUS-PG-T206 Music and Media Theory 4 100 Semester III 20 500 MUS-PG-T301 Modern Traditions of Indian Music Theory 4 100 MUS-PG-P302 Analytical Study of Tala-III Practical 4 100 MUS-PG-P303 Raga Studies III Practical 4 100 MUS-PG-P303 Tala Studies III Practical 4 100 MUS-PG-P304 Stage Performance I Practical 4 100 MUS-PG-T305 Music and Management Theory 4 100 Semester IV 16 400 MUS-PG-T401 Ethnomusicology Theory 4 100 MUS-PG-T402 Dissertation Theory 4 100 MUS-PG-P403 Raga Studies IV Practical 4 100 MUS-PG-P404 Tala Studies IV Practical 4 100 MUS-PG-P405 Stage Performance II Practical 4 100 1 Semester I MUS-PG-CT101:- Aesthetic Course Detail- The course will primarily provide an overview of music and allied issues like Aesthetics. The discussions will range from Rasa and its varieties [According to Bharat, Abhinavagupta, and others], thoughts of Rabindranath Tagore and Abanindranath Tagore on music to aesthetics and general comparative. -

University of Mauritius Mahatma Gandhi Institute

University of Mauritius Mahatma Gandhi Institute Regulations And Programme of Studies B. A (Hons) Performing Arts (Vocal Hindustani) (Review) - 1 - UNIVERSITY OF MAURITIUS MAHATMA GANDHI INSTITUTE PART I General Regulations for B.A (Hons) Performing Arts (Vocal Hindustani) 1. Programme title: B.A (Hons) Performing Arts (Vocal Hindustani) 2. Objectives To equip the student with further knowledge and skills in Vocal Hindustani Music and proficiency in the teaching of the subject. 3. General Entry Requirements In accordance with the University General Entry Requirements for admission to undergraduate degree programmes. 4. Programme Requirement A post A-Level MGI Diploma in Performing Arts (Vocal Hindustani) or an alternative qualification acceptable to the University of Mauritius. 5. Programme Duration Normal Maximum Degree (P/T): 2 years 4 years (4 semesters) (8 semesters) 6. Credit System 6.1 Introduction 6.1.1 The B.A (Hons) Performing Arts (Vocal Hindustani) programme is built up on a 3- year part time Diploma, which accounts for 60 credits. 6.1.2 The Programme is structured on the credit system and is run on a semester basis. 6.1.3 A semester is of a duration of 15 weeks (excluding examination period). - 2 - 6.1.4 A credit is a unit of measure, and the Programme is based on the following guidelines: 15 hours of lectures and / or tutorials: 1 credit 6.2 Programme Structure The B.A Programme is made up of a number of modules carrying 3 credits each, except the Dissertation which carries 9 credits. 6.3 Minimum Credits Required for the Award of the Degree: 6.3.1 The MGI Diploma already accounts for 60 credits. -

Downbeat.Com December 2014 U.K. £3.50

£3.50 £3.50 . U.K DECEMBER 2014 DOWNBEAT.COM D O W N B E AT 79TH ANNUAL READERS POLL WINNERS | MIGUEL ZENÓN | CHICK COREA | PAT METHENY | DIANA KRALL DECEMBER 2014 DECEMBER 2014 VOLUME 81 / NUMBER 12 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Editor Bobby Reed Associate Editor Davis Inman Contributing Editor Ed Enright Art Director LoriAnne Nelson Contributing Designer Žaneta Čuntová Bookkeeper Margaret Stevens Circulation Manager Sue Mahal Circulation Associate Kevin R. Maher Circulation Assistant Evelyn Oakes ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile 630-941-2030 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney 201-445-6260 [email protected] Advertising Sales Associate Pete Fenech 630-941-2030 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road, Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 / Fax: 630-941-3210 http://downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 / [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, Aaron Cohen, Howard Mandel, John McDonough Atlanta: Jon Ross; Austin: Kevin Whitehead; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank- John Hadley; Chicago: John Corbett, Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Mitch Myers, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Denver: Norman Provizer; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Iowa: Will Smith; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Todd Jenkins, Kirk Silsbee, Chris Walker, Joe Woodard; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Robin James; Nashville: Bob Doerschuk; New Orleans: Erika Goldring, David Kunian, Jennifer Odell; New York: Alan Bergman, -

What They Say

WHAT THEY SAY What THEY SAY Mrs. Kishori Amonkar 27-02-1999 “It was great performing in the new reconstructed Shanmukhananda Hall. It has improved much from the old one, but still I’ve a few suggestions to improve which I’ll write to the authorities later” Pandit Jasraj 26-03-1999 “My first concert here after the renovation. Beautiful auditorium, excellent acoustics, great atmosphere - what more could I ask for a memorable concert here for me to be remembered for a long long time” Guru Kelucharan Mohapatra 26-03-1999 “It is a great privilege & honour to perform here at Shanmukhananda Auditorium. Seeing the surroundings here, an artiste feeling comes from inside which makes a performer to bring out his best for the art lovers & the audience.” Pandit Birju Maharaj 26-03-1999 “ yengle mece³e kesÀ yeeo Fme ceW efHeÀj DeekeÀj GmekeÀe ve³ee ©He osKekeÀj yengle Deevevo ngDee~ Deeies Yeer Deeles jnW ³en keÀecevee keÀjles ngS~ μegYe keÀecevee meefnle~” Ustad Vilayat Khan 31-03-1999 “It is indeed my pleasure and privilege to play in the beautiful, unique and extremely musical hall - which reconstructed - renovated is almost like a palace for musicians. I am so pleased to be able to play today before such an appreciative audience.” § 34 § Shanmukhananda culture redefined2A-Original.indd 34 02/05/19 9:02 AM Sant Morari Bapu 04-05-1999 “ cesjer ÒemeVelee Deewj ÒeYeg ÒeeLe&vee” Shri L. K. Advani 18-07-1999 “I have come to this Auditorium after 10 years, for the first time after it has been reconstructed. -

Download Full Length Paper

International Journal of Research in Social Sciences Vol. 8 Issue 10, October 2018, ISSN: 2249-2496 Impact Factor: 7.081 Journal Homepage: http://www.ijmra.us, Email: [email protected] Double-Blind Peer Reviewed Refereed Open Access International Journal - Included in the International Serial Directories Indexed & Listed at: Ulrich's Periodicals Directory ©, U.S.A., Open J-Gate as well as in Cabell’s Directories of Publishing Opportunities, U.S.A The Importance of Music as a foundation of Mental Peace Dr. Sandhya Arora, Associate Professor, Department of Music, S.S. KhannaGirls’ Degree College, Allahabad. MUSIC FOR THE PEACE OF MIND Shakespeare once wrote: "If music be the food of love, play on..." Profound words, true, but he failed to mention that music is not just nourishment for the heart, but also for the soul. Music surrounds our lives, we hear it on the radio, on television, from our car and home stereos. We come across it in the mellifluous tunes of a classical concert or in the devotional strains of a bhajan, the wedding band, or the reaper in the fields breaking into song to express the joy of life. Even warbling in the bathroom gives us a happy start to the day. Music can delight all the senses and inspire every fiber of our being. Music has the power to soothe and relax, bring us comfort and embracing joy! Music subtly bypasses the intellectual stimulus in the brain and moves directly to our subconscious There is music for every mood and for every occasion. Many cultures recognize the importance of music and sound as a healing power.