640 Review Essays

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Democracy in Chains”, by Nancy Maclean.1 Additional Material on the Koch Brothers Can Be Found in “Dark Money”, by Jane Mayer

1 Neoliberalism, The Koch Brothers And Their Attack On Democracy This discussion is based on the book, “Democracy in Chains”, by Nancy MacLean.1 Additional material on the Koch brothers can be found in “Dark Money”, by Jane Mayer. 2 Brief history of the neoliberal movement Larry Kramer, formerly Dean of the Law School at Stanford University and now the director of the William and Flora Hewlett Philanthropic Foundation, recently called neoliberalism the 3 “dominant intellectual and political force of our time.” What is 'neoliberalism', and how did it come to be such an economic force to be reckoned with? According to Wikipedia, th “neoliberalism” was used during the 19 century to describe a laissez-faire type of capitalism; one that advocated for the privatization of industry, loosening of federal regulations, lowered taxes and fiscal austerity. The term dropped from general usage and then was resurrected in the mid-twentieth century by the Nobel Prize-winning, conservative economist, James M. Buchanan. Buchanan used it to advocate for a society in which spending on social programs had all but been eliminated and taxes on wealthy individuals and big businesses had been reduced. More than just theory, neoliberalism has, in fact, been tried in South America and with disastrous results. In Chile, during the 1970's and 80's when Augusto Pinochet was in power, Buchanan himself served as financial advisor to the Pinochet regime and put into effect a program of austerity that resulted in great hardship for the average citizen while 4 benefiting the rich or the elite soon to be rich. -

Judicial Patriarchy and Domestic Violence: a Challenge to the Conventional Family Privacy Narrative Elizabeth Katz

William & Mary Journal of Women and the Law Volume 21 | Issue 2 Article 5 Judicial Patriarchy and Domestic Violence: A Challenge to the Conventional Family Privacy Narrative Elizabeth Katz Repository Citation Elizabeth Katz, Judicial Patriarchy and Domestic Violence: A Challenge to the Conventional Family Privacy Narrative, 21 Wm. & Mary J. Women & L. 379 (2015), http://scholarship.law.wm.edu/ wmjowl/vol21/iss2/5 Copyright c 2015 by the authors. This article is brought to you by the William & Mary Law School Scholarship Repository. http://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmjowl JUDICIAL PATRIARCHY AND DOMESTIC VIOLENCE: A CHALLENGE TO THE CONVENTIONAL FAMILY PRIVACY NARRATIVE ELIZABETH KATZ* ABSTRACT According to the conventional domestic violence narrative, judges historically have ignored or even shielded “wife beaters” as a result of the patriarchal prioritization of privacy in the home. This Article directly challenges that account. In the early twentieth century, judges regularly and enthusiastically protected female victims of domestic violence in the divorce and criminal contexts. As legal and economic developments appeared to threaten American manhood and tra- ditional family structures, judges intervened in domestic violence matters as substitute patriarchs. They harshly condemned male per- petrators—sentencing men to fines, prison, and even the whipping post—for failing to conform to appropriate husbandly behavior, while rewarding wives who exhibited the traditional female traits of vul- nerability and dependence. Based on the same gendered reasoning, judges trivialized or even ridiculed victims of “husband beating.” Men who sought protection against physically abusive wives were deemed unmanly and undeserving of the legal remedies afforded to women. Although judges routinely addressed wife beating in divorce and criminal cases, they balked when women pursued a third type of legal action: interspousal tort suits. -

The Billionaire Behind Efforts to Kill the U.S. Postal Service by Lisa Graves/True North Research for in the Public Interest

The Billionaire Behind Efforts to Kill the U.S. Postal Service By Lisa Graves/True North Research for In the Public Interest JULY 2020 About Lisa Graves Lisa Graves is the Executive Director of True North and its editor-in-chief. She has spearheaded several major breakthrough investigations into those distorting American democracy and public policy. Her research and analysis have been cited by every major paper in the country, and featured in critically acclaimed books and documentaries including Ava DuVernay’s “The 13th.” She has appeared frequently on MSNBC as a guest on Last Word with Lawrence O’Donnell as well as on other MSNBC shows. She has also served as a guest expert on CNN, ABC, NBC, CBS, CNBC, BBC, C-SPAN, Amy Goodman’s Democracy Now!, the Laura Flanders Show, and other news shows. She’s written for the New York Times, Slate, TIME, the Nation, In These Times, the Progressive, PRWatch, Common Dreams, Yes!, and other outlets. Her research is cited in major books such as Dark Money by Jane Mayer, Give Us the Ballot by Ari Berman, Corporate Citizen by Ciara Torres-Spelliscy, The Fall of Wisconsin by Dan Kaufman, and others. About In the Public Interest In the Public Interest is a research and policy center committed to promoting the common good and democratic control of public goods and services. We help citizens, public officials, advocacy groups, and researchers better understand the impacts that government contracts and public-private agreements have on service quality, democratic decision- making, and public budgets. Our goal is to ensure that government contracts, agreements, and related policies increase transparency, accountability, efficiency, and shared prosperity through the provision of public goods and services. -

Manifesto for a Humane True Libertarianism

Manifesto for a Humane True Libertarianism Deirdre Nansen McCloskey July 4, 2018 The first chapters of Humane True Liberalism, forthcoming 2019, Yale University Press. All rights reserved. #1. Libertarians are liberals are democrats are good I make here the case for a new and humane version of what is often called “libertarianism.” Thus the columnist George Will at the Washington Post or David Brooks at the New York Times or Steve Chapman at the Chicago Tribune or Dave Barry at the Miami Herald or P. J . O'Rourke at the National Lampoon, Rolling Stone, and the Daily Beast. Humane libertarianism is not right wing or reactionary or some scary creature out of Dark Money. In fact, it stands in the middle of the road—recently a dangerous place to stand—being tolerant and optimistic and respectful. It’s True Liberal, anti- statist, opposing the impulse of people to push other people around. It’s not “I’ve got mine," or “Let’s be cruel.” Nor is it “I’m from the government and I’m here to help you, by force of arms if necessary.” It’s “I respect your dignity, and am willing to listen, really listen, helping you if you wish, on your own terms.” When people grasp it, many like it. Give it a try. In most of the world the word “libertarianism” is still plain "liberalism," as in the usage of the middle-of-the-road, anti-“illiberal democracy” president of France elected in 2017, Emmanuel Macron, with no “neo-” about it. That's the L-word I’ll use here. -

Why and How the Koch Network Uses Disinformation to Thwart Democracy

“Since We Are Greatly Outnumbered”: Why and How the Koch Network Uses Disinformation to Thwart Democracy Nancy MacLean, Duke University For A Modern History of the Disinformation Age: Media, Technology, and Democracy in Historical Context Social Science Research Council *** Draft: please do not circulate without permission of the author *** ABSTRACT: This chapter examines one source of the strategic disinformation now rife in American public life: the Koch network of extreme right donors, allied organizations, and academic grantees. I argue that the architects of this network’s project of radical transformation of our institutions and legal system have adopted this tactic in the knowledge that the hard-core libertarian agenda is extremely unpopular and therefore requires stealth to succeed. The chapter tells the story of how Charles Koch and his inner circle, having determined in the 1970s that changes significant enough to constitute a “constitutional revolution” (in the words of the political economist James McGill Buchanan) would be needed to protect capitalism from democracy, then went about experimenting to make this desideratum a reality. In the 1980s, they first incubated ideas for misleading the public to move their agenda, as shown by the strategy for Social Security privatization that Buchanan recommended to Koch’s Cato Institute, and by the operations of Citizens for a Sound Economy, the network’s first and very clumsy astroturf organizing effort. In the light of these foundational efforts, subsequent practices of active disinformation by this network become more comprehensible as driven by a mix of messianic dogma and self-interest for a project that cannot succeed by persuasion and organizing alone in the usual manner. -

The Public Eye, Summer 2017

SUMMER 2017 The Public Eye In this issue: The Christian Right and Fourth Generation Warfare How Antisemitism Animates White Nationalism When Prison Ministries Prioritize Salvation Over Justice Charles Koch and the Makings of a Right-Wing Empire editor’s letter As the summer issue of The Public Eye ships to the printers, it’s been a whirlwind week. THE PUBLIC EYE Republicans’ efforts to overthrow Obamacare failed dramatically in the early hours of July QUARTERLY 28, but this victory followed some of the Trump administration’s most aggressive anti- PUBLISHER LGBTQ actions to date. Trump delivered an unprecedentedly ugly partisan speech to the Boy Tarso Luís Ramos Scouts of America, endorsed police brutality to a law enforcement audience, and publicly EDITOR mused about firing officials over the ongoing Russia investigation and pardoning himself Kathryn Joyce for what they may find. As many are now questioning if the administration is on a messy COVER ART slide towards authoritarianism, this issue homes in on some of what got us here. Ashley Lukashevsky Sociologist and former civilian intelligence analyst James Scaminaci takes a close look at a little-known right-wing strategy developed in LAYOUT “Fourth Generation Warfare” (pg. 4), Gabriel Joffe the 1980s and deployed over decades by strategists Paul Weyrich and William S. Lind. A fusion of military theory and the Christian Right agenda, Fourth Generation Warfare seeks PRINTING Red Sun Press to undermine the public’s confidence not just in the government and media, but in a com- monly-accepted reality itself. The result, Scaminaci writes, is “an all-out propaganda war EDITORIAL BOARD against secular liberalism” and the political mainstream, waged “with the same intensity Frederick Clarkson • Alex DiBranco as a shooting war.” Fourth Generation Warfare, he argues, set the template for Trump’s no- Tope Fadiran • Gabriel Joffe Kapya Kaoma • Greeley O’Connor holds-barred campaign against the political establishment. -

The Disinformation Age

Steven Livingston W. LanceW. Bennett EDITED BY EDITED BY Downloaded from terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/product/1F4751119C7C4693E514C249E0F0F997THE DISINFORMATION AGE https://www.cambridge.org/core Politics, and Technology, Disruptive Communication in the United States the United in https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms . IP address: 170.106.202.126 . , on 27 Sep 2021 at 12:34:36 , subject to the Cambridge Core Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. IP address: 170.106.202.126, on 27 Sep 2021 at 12:34:36, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://www.cambridge.org/core/product/1F4751119C7C4693E514C249E0F0F997 The Disinformation Age The intentional spread of falsehoods – and attendant attacks on minorities, press freedoms, and the rule of law – challenge the basic norms and values upon which institutional legitimacy and political stability depend. How did we get here? The Disinformation Age assembles a remarkable group of historians, political scientists, and communication scholars to examine the historical and political origins of the post-fact information era, focusing on the United States but with lessons for other democracies. Bennett and Livingston frame the book by examining decades-long efforts by political and business interests to undermine authoritative institutions, including parties, elections, public agencies, science, independent journalism, and civil society groups. The other distinguished scholars explore the historical origins and workings of disinformation, along with policy challenges and the role of the legacy press in improving public communication. This title is also available as Open Access on Cambridge Core. W. Lance Bennett is Professor of Political Science and Ruddick C. -

Center for Study of Public Choice

Center for Study of Public Choice Annual Report 2019–2020 From the Director As I write, COVID-19 has killed more than seven hundred thousand people in the world, including over 150 thousand Americans. The IMF estimates that in 2020-2021, the total economic loss will be over $12 trillion. Not surprisingly, the crisis has also affected the Center for Study of Public Choice. Most notably, we reluctantly cancelled the annual Public Choice Outreach Conference, the first time the conference hasn’t been held in decades. Center scholars, however, continued their work and in several cases swung into action on COVID. Tyler Cowen, for example, raised millions of dollars for COVID funding and delivered it to worthy projects before the NIH even completed one grant! See his FastGrants project. Other contributions are documented in the report. Alex Tabarrok As the crisis began to accelerate, I wrote a primer, Grand Innovation Prizes to Address Pandemics, that advocated for prizes. The piece led to a meeting with U.S. policy makers, at which Michael Kremer and I spoke. Kremer had won the Nobel prize in 2019 in part for his work in creating an advance market commitment, a kind of prize, for a pneumococcus vaccine. The vaccine was produced, and the AMC likely saved over 700,000 lives. After the meeting, we were asked to follow-up with a written proposal. Kremer then called on his contacts around the world to help. And that is how I found myself working with a team of all-star economists to design an incentive program for vaccines. -

Truth Dialogue Maclean 9 27 17 by Samantha Schmidt

A Truth Dialogues Report/Reflection by Samantha Schmidt Franke Undergraduate Fellow of the Kaplan Humanities Institute ——————————————————————————————————————— Democracy in Chains (Nancy MacLean—September 27, 2017) The first event in the 2017-2018 Truth Dialogues series, Nancy MacLean’s talk about her new book Democracy in Chains: The Deep History of the Radical Right’s Stealth Plan for America, had the feel and festivity of a homecoming event. Having taught at Northwestern for over twenty years and chaired the History Department from 2005 to 2008, McLean left her mark on the university in a multitude of ways. At the start of her talk, she joked about her pride in the skylight that shines over the stairs in Harris Hall, an addition whose necessity, she assured the audience, she had vehemently insisted upon, though she no longer recalls the reason. More touching was the moving introduction that Professor Michael Allen, on whose dissertation committee she had sat back in 2003, gave at the opening of the event. As in any introduction, he celebrated her accomplishments in academia and social justice organizing, but their personal relationship enabled him to delve deeper. He called her “as exacting and brave as she is generous and caring,” a sentiment that the audience, which had filled the hall to the point that the lecture became standing-room-only, greeted with approval. Ironically, however, McLean made clear over the course of the talk that her book would not have been possible had she remained at Northwestern. The research that led to the book was partially inspired by McLean’s move to Duke University and to North Carolina, which coincided with the 2010 midterm elections. -

A Manifesto for a New Liberalism, Or How to Be a Humane Libertarian

Introduction to How to be a Humane Libertarian: Essays for a New Liberalism, forthcoming 2018 or 2019, Yale University Press A manifesto for a new liberalism, or How to be a humane libertarian 1. Libertarians are liberals I make the case here for a new and humane “libertarianism.” Libertarianism is not conservative. It stands in fact somewhere in the middle of the road, often a hazardous location, being tolerant and optimistic and respectful. It’s True Liberal. When people come to actually understand it, most like it. Give it a try. Outside the United States libertarianism is still called plain "liberalism," as in the usage of the middle-of-the-road president of France, Emmanuel Macron, with no “neo-” about it. That's the L-word I’ll use here. The political philosopher John Tomasi calls its alliance with modern democracy “the liberalism of the common man.” One thinks of Walt Whitman singing of the democratic and liberal individual, “I contain multitudes.” Such people, it turned out, actually did, containing multitudes of abilities for self-government and for economic and spiritual progress never before tapped—something which is disbelieved still by conservatives and progressives. Our friends on right and left wish to rule and to nudge their fellow adults. They see people as disgracefully barbarous or sadly incompetent. We liberals don’t. The American economist Daniel Klein calls what Tomasi and Whitman and I are praising "Liberalism 1.0," or, channeling the old C. S. Lewis book on the minimum commitments of faith, Mere Christianity (1942-44, 1952), "mere Liberalism."1 David Boaz of the liberal Cato Institute in Washington wrote a lucid guide, Libertarianism—A Primer (1997), reshaped in 2015 as The Libertarian Mind. -

October-2017.Pdf

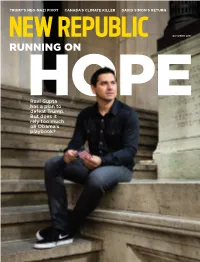

Inside stories of how activist staffers countered corporate lobbies “A wonderful read.” — ROBERT REICH “ Witty and penetrating…” — NORMAN ORNSTEIN “ This book is the story of a public servant … and his fellow activist staffers, whose valiant work on consumer protection has helped millions of Americans.” — RALPH NADER “A lively and thought- provoking book…” — JAMES A. THURBER “ This may be the most important political book written about our current political dysfunction…” — MATT MYERS Available now in jacketed cloth & ebook formats. Visit us at www.vanderbiltuniversitypress.com. contents OCTOBER 2017 UP FRONT 6 The New Fight for Labor Rights 18 To survive, the labor movement needs to rethink its strategy. BY RACHEL M. COHEN 8 Losing Hearts and Minds How Trump quietly gutted a program to combat extremism. BY BENJAMIN POWERS 9 The Trump Tweetometer A look inside the president’s mind, based on his first seven months of tweets. 10 The Next Standing Rock Why is Canada green-lighting a pipeline that could kill the climate? BY BEN ADLER 12 Art of the Steal How Trump’s self-dealing helped make his book a best-seller. BY ALEX SHEPHARD COLUMNS 14 Deadbeat Democrats How Bill Clinton set the stage for the GOP’s war on the poor. BY BRYCE COVERT Lauren Underwood, 16 a nurse from Illinois, Redoing the Electoral Math is a candidate for Congress. It will take more than demographics to save the Democrats. BY JOHN B. JUDIS Running on Hope REVIEW 46 Rules for Radicals A new group of Obama aides aims to take down Trump. The right-wing economist who rigged But can Democrats win without a unified message? democracy for the rich. -

The Role of White Nationalism in Us

THE GATHERING STORM: THE ROLE OF WHITE NATIONALISM IN U.S. POLITICS GENIE A. DONLEY Bachelor of Arts in History Cleveland State University May 2016 submitted in partial fulfillment of requirements for the degree MASTER OF ARTS IN HISTORY at CLEVELAND STATE UNIVERSITY May 2018 We hereby approve this Master’s thesis For Genie A. Donley Candidate for the Master of Arts degree in History for the Department of History And CLEVELAND STATE UNIVERSITY’S College of Graduate Studies by _________________________________________________ Thomas J. Humphrey, Ph.D. History Department _________________________________________________ Robert S. Shelton, Ph.D. History Department _________________________________________________ Karen Sotiropoulos, Ph.D. History Department Student’s Date of Defense: April 18, 2018 DEDICATION To my son, David, and to my advisor, Dr. Thomas J. Humphrey. THE GATHERING STORM: THE ROLE OF WHITE NATIONALISM IN U.S. POLITICS GENIE A. DONLEY ABSTRACT White nationalism has played a critical role in shaping United States politics for over 150 years. Since the Reconstruction era, whites have fought to maintain their power and superiority over minorities. They influenced U.S. politics by attempting, and in some cases succeeding, to prevent minorities from voting. Moreover, politicians began to help them. This became most evident in the 2016 U.S. presidential election when Republican Donald J. Trump appealed to racist white voters, gained their support, and won the election. Those voters, who united as the Alt-Right, supported Trump because he appealed to them by playing on their fear of becoming a minority in their country. This thesis traces white nationalism back to Reconstruction. It analyzes the memberships of separate groups such as the Ku Klux Klan, Neo-Confederates, and Citizens’ Councils to show how and why those various groups united as the Alt-Right to support Trump in the 2016 election.