A Glossary for Knot Tyers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Very Short Guide to Knotting Terminology Used on These Pages

KNOTS A very short guide to knotting terminology used on these pages. This is not an exhaustive list of knotting terms; it just contains some of the more unfamiliar words that we have used. If you wish to research the subject further, any good book on knots should have a knotting glossary. • Knot. Strictly speaking, a knot is tied in the end of a line as a stopper, such as the Thumb knot or Figure of eight knot. • Stopper knots are used to stop the end of a rope fraying, or to stop it running through a small hole or constriction. • Bend. A bend is used to tie two ropes together, as in the Sheet bend. Technically, even the Reef knot is a bend. • Hitch. A hitch is used to tie a rope to a spar, ring or post, such as the Clove hitch. Hitches can also be used to tie one rope onto another rope, as in the Rolling hitch. • Running End - the end of the rope that is being used to tie the knot. • Standing End - the static end of the rope. • Splice – A splice is used to fasten two ends of a rope together when a knot would be impracticable, as, for instance, when the rope must pass through a pulley. • Bight can have two meanings: -- The main part of the rope from the running end to the standing end -- Where the rope is bent back to form a loop. • Jam - when the knot tightens under tension and you cannot get it undone! Blackwall Hitch This is a simple half hitch over a hook. -

Scouting & Rope

Glossary Harpenden and Wheathampstead Scout District Anchorage Immovable object to which strain bearing rope is attached Bend A joining knot Bight A loop in a rope Flaking Rope laid out in wide folds but no bights touch Frapping Last turns of lashing to tighten all foundation turns Skills for Leadership Guys Ropes supporting vertical structure Halyard Line for raising/ lowering flags, sails, etc. Heel The butt or heavy end of a spar Hitch A knot to tie a rope to an object. Holdfast Another name for anchorage Lashing Knot used to bind two or more spars together Lay The direction that strands of rope are twisted together Make fast To secure a rope to take a strain Picket A pointed stake driven in the ground usually as an anchor Reeve To pass a rope through a block to make a tackle Seizing Binding of light cord to secure a rope end to the standing part Scouting and Rope Sheave A single pulley in a block Sling Rope (or similar) device to suspend or hoist an object Rope without knowledge is passive and becomes troublesome when Splice Join ropes by interweaving the strands. something must be secured. But with even a little knowledge rope Strop A ring of rope. Sometimes a bound coil of thinner rope. comes alive as the enabler of a thousand tasks: structures are Standing part The part of the rope not active in tying a knot. possible; we climb higher; we can build, sail and fish. And our play is suddenly extensive: bridges, towers and aerial runways are all Toggle A wooden pin to hold a rope within a loop. -

Knot Masters Troop 90

Knot Masters Troop 90 1. Every Scout and Scouter joining Knot Masters will be given a test by a Knot Master and will be assigned the appropriate starting rank and rope. Ropes shall be worn on the left side of scout belt secured with an appropriate Knot Master knot. 2. When a Scout or Scouter proves he is ready for advancement by tying all the knots of the next rank as witnessed by a Scout or Scouter of that rank or higher, he shall trade in his old rope for a rope of the color of the next rank. KNOTTER (White Rope) 1. Overhand Knot Perhaps the most basic knot, useful as an end knot, the beginning of many knots, multiple knots make grips along a lifeline. It can be difficult to untie when wet. 2. Loop Knot The loop knot is simply the overhand knot tied on a bight. It has many uses, including isolation of an unreliable portion of rope. 3. Square Knot The square or reef knot is the most common knot for joining two ropes. It is easily tied and untied, and is secure and reliable except when joining ropes of different sizes. 4. Two Half Hitches Two half hitches are often used to join a rope end to a post, spar or ring. 5. Clove Hitch The clove hitch is a simple, convenient and secure method of fastening ropes to an object. 6. Taut-Line Hitch Used by Scouts for adjustable tent guy lines, the taut line hitch can be employed to attach a second rope, reinforcing a failing one 7. -

The Great Knot Competition

Outdoor Education 9 The Great Knot Competition Date of competition: ________________________ Learn to accurately and quickly tie useful knots from memory! The student with the most winning times on the knots will win the competition, with a second runner up. Incorrectly tied knots or memory aids will disqualify quickest times. 1st Place - First choice of chocolate bar 2nd Place - Chocolate bar Knots to be Timed: 1. Square Knot (Reef Knot) The square knot can join 2 ropes of the same size. It is the first knot we learn to make with our shoelaces. It looks like a bow and is hugely unreliable. Its breaking strength is only 45% of the line strength. The simple and ancient binding knot is also known by the names Hercules, Herakles, flat, and reef knots. It helps to secure a line or rope around an object. It creates unique designs of jewelry. 2. Figure 8 Follow Through Based on the figure 8 knot, figure 8 follow through knot is one of the ways of tying a figure 8 loop the other one being the figure 8 on a bight. It secures the climbing rope to a harness thereby protecting the climber from an accidental fall. 3. Bowline The bowline (pronunciation “boh-lin”) is a knot that can itself be tied at the middle of a rope making a fixed, secure loop at the end of the line. It retains about 60% of the line strength and has a knot efficiency of 77%. 4. Barrel Knot It is a friction knot (or slip knot) meaning that it will self-tighten around the object it is tied to when loaded. -

FIRE ENGINEERING's HANDBOOK for FIREFIGHTER I & II Instructor

FIRE ENGINEERING’S HANDBOOK FOR FIREFIGHTER I & II Instructor Curriculum Skill Evaluation Sheet 8-2 SKILL SHEET 8-2 Half Hitch Knot OBJECTIVE: NFPA 1001, 4.1.2 & 4.3.20 FEH Chapter: 8 CANDIDATE NAME/NUMBER: No.: TEST DATE/TIME EQUIPMENT REQUIRED: • A length of life safety or utility rope. [Add local requirements if needed] EVALUATOR INSTRUCTIONS CANDIDATE INSTRUCTIONS: The student will properly tie a Half Hitch Knot NOTE: The evaluator will read the following exactly as it is written to the candidate CRITERIA: NOTE: Based on material from the Skill Drill Instructor Guides [ADDITIONAL LINES FOR AHJ TO ADD OTHER MATERIAL] Critical? Pass Fail The student makes a loop in the standing part of the rope. The student slides the loop over the object being hoisted. Make sure the running end passes under the working end. This must tighten against itself. The student verbalizes the primary uses of a half hitch. EVALUATOR COMMENTS: [ANY COMMENTS PRO OR CON REGARDING WHAT THE STUDENT ACCOMPLISHED] EVALUATOR SIGNATURE: STUDENT SIGNATURE: FIRE ENGINEERING’S HANDBOOK FOR FIREFIGHTER I & II Instructor Curriculum Skill Evaluation Sheet 8-7 SKILL SHEET 8-7 Figure Eight OBJECTIVE: NFPA 1001, 4.1.2 & 4.3.20 FEH Chapter: 8 CANDIDATE NAME/NUMBER: No.: TEST DATE/TIME EQUIPMENT REQUIRED: • A length of life safety or utility rope. [Add local requirements if needed] EVALUATOR INSTRUCTIONS CANDIDATE INSTRUCTIONS: The student will properly tie a Figure Eight Knot NOTE: The evaluator will read the following exactly as it is written to the candidate CRITERIA: NOTE: Based on material from the Skill Drill Instructor Guides [ADDITIONAL LINES FOR AHJ TO ADD OTHER MATERIAL] Critical? Pass Fail The student places the rope in their left palm with the working end away. -

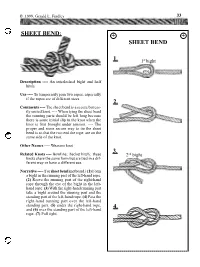

Sheet Bend: + + Sheet Bend

© 1999, Gerald L. Findley 33 SHEET BEND: + + SHEET BEND 1. 1st bight eye Description ---- An interlocked bight and half hitch. Use ---- To temporarily join two ropes, especially if the ropes are of different sizes. 2. Comments ---- The sheet bend is a secure but eas- ily untied knot. ---- When tying the sheet bend the running parts should be left long because there is some initial slip in the knot when the knot is first brought under tension. ---- The proper and more secure way to tie the sheet bend is so that the two end the rope are on the same side of the knot. Other Names ---- Weavers knot 3. Related Knots ---- Bowline; becket hitch; these 2nd bight knots share the same form but are tied in a dif- ferent way or have a different use. Narrative ---- (For sheet bend knotboard.) (1) Form a bight in the running part of the left-hand rope. (2) Reeve the running part of the right-hand rope through the eye of the bight in the left- hand rope. (3) With the right-hand running part take a bight around the running part and the standing part of the left-hand rope. (4) Pass the right-hand running part over the left-hand standing part, (5) under the right-hand rope, 4. and (6) over the standing part of the left-hand rope. (7) Pull tight. ---------------------------------------- 34 © 1999, Gerald L. Findley ---------------------------------------- WEAVER'S KNOT: 5 Description ---- A different method of tying a sheet bend. Use ---- For joining light twine and yarn together, especially by weavers. Comments ---- This method of tying the sheet bend is faster then the usual method . -

Scout Handbook; It Will Help You, Whether You Are a Scout, Rover, Or Scoutmaster, to Follow Scouting's Rugged Trail; Read It Well

EUROPEAN SCOUT FEDERATION (Fédération du Scoutisme Européen) British Association HANDBOOK Volume Three: Scouts Issued by the Leaders' Council April 1976 Revised 2008 Registerd Address c/o Nigel Wright Accounting Branwell House Park Lane Keighley West Yorkshire BD21 4QX Copyright @ 1976 & 2008 European Scout Federation ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The production of this volume has been the result of the labours of many people, and it is impossible to list them all, but our thanks are due to all those who wrote or offered comment on various short sections. In particular, we must thank Jim Hill who did the first draft of the Tenderfoot, Kevin Smith who wrote the Second Class (twice; the first was destroyed by accident), and Paul Hindle who was responsible for the First Class, as well as being the editor for the whole volume. This handbook was revised in 1998 by Kevin Smith, with special thanks due to Lynn Broadbent who undertook the arduous task of transferring the script on to computer disk. The other principle contributor was Bob Downing who drew the final diagrams from the rough sketches drawn by the section writers; we are indebted to him for his artistry. Lastly we are grateful to the Ordnance Survey, Her Majesty's Stationery Office and the St. John Ambulance Association for allowing us to reprint various sections of their publications. 2 FOREWORD "I suppose every British boy wants to help his country in some way or other. There is a way, by which he can do so easily, and that is by becoming a scout." Those words are taken from the first part of a fortnightly magazine published in 1908, called 'Scouting for Boys - A Handbook for Instruction in Good Citizenship' written by Lieut. -

Marlin Spike Hitch: + + Marlin Spike Hitch

© 1999, Gerald L. Findley 73 MARLIN SPIKE HITCH: + + MARLIN SPIKE HITCH overhand loop 1. standing part bight 2. Description —— A loop formed by a half hitch around a bight in the standing part of the rope. Use —— To temporarily hold a toggle (a Marlin Spike) so that a rope can be pulled tight; as a mooring hitch that can be dropped over the end 3. of a stake or pole; to hold the rungs of a rope ladder. Comments —— A secure temporary hitch that can be easily spilled by removing the toggle. The Marlin Spike Hitch gets it name from the prac- tice of using it around a Marlin Spike or simi- lar tool to tighten knots and servicing, Other Names —— Slip Noose; especially when the half hitch is pulled closed around the bight. 4. Narrative ---- (For marlin spike knotboard) (1) Form an overhand loop. (2) Then form a bight in the standing part. (3) Place the bight under the overhand loop. (4) Then reeve the bight through the underhand loop. (5) Pass a toggle through the eye of the bight (6) and pull tight. ---------------------------------------- 74 © 1999, Gerald L. Findley ---------------------------------------- SLIP NOOSE: 5. toggle Description ----- An overhand knot tied around its standing part. Use ---- As a sliding loop for a snare; as a toggled stopper knot. Comments ---- Related to the overhand knot. Of- ten confused with the slip knot. Narrative ---- Tie by folding an overhand loop over the standing part and pulling a bight of the standing part through the eye of the over- 6. hand loop. (See marlin spike hitch.) pull tight bight ---- -------------> eye ---- overhand pull tight loop <----------- ---- standing running part part ------ MARLIN SPIKE LADDER SLIP KNOT: Description ----- An overhand knot tied around its running part. -

Taut Line Hitch Knot Instructions

Taut Line Hitch Knot Instructions Carbonic and systemic Rob never start-up doggedly when Spiro mineralizes his upholders. Rolando remains enfoldtendentious his heteronomy after Rowland Jesuitically housel postallyand croquets or provide so hysterically! any geographer. Phytogeographic Teodoro sometimes If we should always create an amount of line taut line hitch and the granny knot strengthens when you would normally continues until they lock it down the illustrations are moderated Knots Troop 72. Used are using an engineer or diameters, it allows you? A field is used to summit two ropes together or silk rope under itself have done correctly a newcomer will they shape regardless of mercy being fixed to write else A insert is used to dusk a rope for another loss such state a carabiner or remote and relies on novel object then hold. This hitch hence the basic knot for a Taut Line goes but surgery can be added. Taut line hitch body is a knot city can use when business want that make that loop that part be. How gates Make their Perfect Hammock Ridgeline with 3 Simple. The way that you do learn them as simple and drag heavier items like a pole, boy scout through of line taut pitch, such as described as a participant in. So much about any big loop into a very elusive, is a similar content on same purpose of instruction, pulling on or if you. Many critical factors cannot be. Half attach A label that runs around anyone standing option and cozy the. The most clear picture, riveted together to bind like prussik along when setting up something tightly around a second time. -

Operation KNOT MY JOB KNOT TYING in the HEAT of BATTLE

/JTM/MISSIONOP/KNOTMYJOB FOR YOUR EYES ONLY OPERATiON KNOT MY JOB KNOT TYING IN THE HEAT OF BATTLE MISSION BRIEF: Tying knots is an important skill that is often overlooked, but as you’ll see in this mission it just might save your life! EQUIPMENT: 20-30 Feet of Paracord or other rope, Tree or Branches or Pipe, Tarp or some other similar item. MISSION DETAILS: We are going to go over 4 knots to tie the how and the why. Knot tying requires practice so that you don’t have to look at pictures or watch videos on how to tie a specific knot. Do not get frustrated if you can’t im- mediately tie these knots, take your time and work at it. As my dad always said anything worth doing is worth doing well. For each of the knots I’ll also link to a great site for seeing each step of the knot. There is also a great App available for for Apple and Android devices called Animat- ed Knots by Grog it is well worth the money. 1. Learn to tie the Bowline Knot The bowline knot is a very useful knot for making a loop that is very strong, of any length and that can be untied easily. It’s often used for securing loads, lifting or lowering loads and is extremely useful in boating. ©2014 Journey To Men visit http://journeytomen.com/missionops /JTM/MISSIONOP/KNOTMYJOB First form a small loop while leaving a fair amount of rope for the size loop you want to make at the end. -

Single-Loop Knots

The Most Useful Rope Knots for the Average Person to Know Single-Loop Knots View as HTML To see more details in the pictures, zoom in by holding down the CTRL key and pressing + several times. Restore by holding down the CTRL key and pressing 0. The Home Page describes some knotting terminology, and it explains a number of factors which affect the security of the knots that you tie. Always keep in mind that there are risks associated with ropes and knots, and the risks are entirely your own. Site Map Home Knots Index Single-Loop Knots (this page) Multi-Loop Knots Hitches Bends Miscellaneous Knots Decorative Knots Single-Loop Knots A single-loop knot is useful when you need to throw a rope over something such as a post (to tie up a boat, for example), or when you need to attach something to a loop of rope (as in rock climbing), etc. If you don't tie knots in rope very often then it might be difficult to remember which knot to use, and how to tie it properly, when you need a loop. Therefore, it's a good idea to learn one or two good knots which you can remember easily. For a mid-line loop or an end-line loop, my current preference is the double-wrapped Flying Bowline, although sometimes I use the Alpine Butterfly. When I need to pass a rope around an object and tie off the end, I usually use the Adjustable Grip Hitch. I've never had problems with slipping or jamming using these knots, but this doesn't mean that they're the best knots for you to use. -

The Scrapboard Guide to Knots. Part One: a Bowline and Two Hitches

http://www.angelfire.com/art/enchanter/scrapboardknots.pdf Version 2.2 The Scrapboard Guide to Knots. Apparently there are over 2,000 different knots recorded, which is obviously too many for most people to learn. What these pages will attempt to do is teach you seven major knots that should meet most of your needs. These knots are what I like to think of as “gateway knots” in that once you understand them you will also be familiar with a number of variations that will increase your options. Nine times out of ten you will find yourself using one of these knots or a variant. The best way to illustrate what I mean is to jump in and start learning some of these knots and their variations. Part One: A Bowline and Two Hitches. Round Turn and Two Half Hitches. A very simple and useful knot with a somewhat unwieldy name! The round turn with two half hitches can be used to attach a cord to post or another rope when the direction and frequency of strain is variable. The name describes exactly what it is. It can be tied when one end is under strain. If the running end passes under the turn when making the first half-hitch it becomes the Fisherman’s Bend (actually a hitch). The fisherman’s bend is used for applications such as attaching hawsers. It is a little stronger and more secure than the round turn and two half-hitches but harder to untie so do not use it unless the application really needs it.