Panel 3 the Aesthetic Imagination Before Chaos: from Self

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

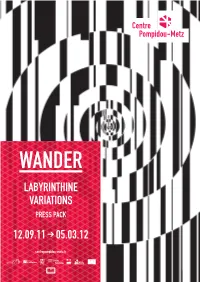

Labyrinthine Variations 12.09.11 → 05.03.12

WANDER LABYRINTHINE VARIATIONS PRESS PACK 12.09.11 > 05.03.12 centrepompidou-metz.fr PRESS PACK - WANDER, LABYRINTHINE VARIATIONS TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION TO THE EXHIBITION .................................................... 02 2. THE EXHIBITION E I TH LAByRINTH AS ARCHITECTURE ....................................................................... 03 II SpACE / TImE .......................................................................................................... 03 III THE mENTAL LAByRINTH ........................................................................................ 04 IV mETROpOLIS .......................................................................................................... 05 V KINETIC DISLOCATION ............................................................................................ 06 VI CApTIVE .................................................................................................................. 07 VII INITIATION / ENLIgHTENmENT ................................................................................ 08 VIII ART AS LAByRINTH ................................................................................................ 09 3. LIST OF EXHIBITED ARTISTS ..................................................................... 10 4. LINEAgES, LAByRINTHINE DETOURS - WORKS, HISTORICAL AND ARCHAEOLOgICAL ARTEFACTS .................... 12 5.Om C m ISSIONED WORKS ............................................................................. 13 6. EXHIBITION DESIgN ....................................................................................... -

Gego Solo Exhibition

GEGO SOLO EXHIBITION 2020 Gego, Museo Jumex, Mexico City, Mexico 2019 Gego, Museo de Arte de São Paulo, São Paul, Brazil 2017 Between the lines. Gego as a printmaker, Amon Carter Museum,Texas, United States Gego. A fascination for line, Kunstmuseum Sttutgart, Sttutgart, Germany Gego en 1969 with “Reticulárea” in Caracas, Venezuela Hamburg, Germany, 1912 - Caracas, Venezuela, 1994 Gego: La poetique de la Ligne, Colección 2014 Gego (Gertrud Goldschmidt) studied architecture and Mercantil, La Maison de la Amerique Latine, engineering at the Stuttgart Technical School Paris, France (Germany), where she was tutored by architect Paul Bonatz, following the models of the Bauhaus and Russian Constructivism. In 1939, due to persecution Gego: Line as Object, Kunstmuseum from the Nazi regime, she migrated to Venezuela, Stuttgart, Stuttgart, Germany making Caracas her home. Once there, Gego dedicated to design, particularly of Gego: Line as Object, Henry Moore furniture, and the development of architectural Institute, Leeds, England projects. Additionally, she began a long teaching career that would lead her to be one of the founders and subsequent professors of the Institute of Design 2013 Gego: El trazo transparente, Museo de la from the Neumann Foundation (Caracas) in 1964. It was during the 1950s that she deepened her artistic Estampa y el Diseño Carlos CruzDiez, practice, which was at first of a figurative, expressionist Caracas, Venezuela type, and then, already in dialogue with kinetic artists like Alejandro Otero and Jesús Soto, of a sculptural type, grounded upon spectator participation, action, Gego: Tejeduras, Bichitos y Libros, Periférico and movement as key principles of production. de Caracas / Arte Contemporáneo/Centro de Arte Los Galpones, Caracas, Venezuela Her work is characterized by the experimentation with lines upon space, conceived as the most elemental unit of drawing, as well as for the innovative use of the Gego: Line as Object, Hamburger Kunsthalle, reticule, a form intimately related to abstraction in Hamburg, Germany modern art. -

Modern Abstraction in Latin America Cecilia Fajardo-Hill

Modern Abstraction in Latin America Cecilia Fajardo-Hill The history of abstraction in Latin America is dense and multilayered; its beginnings can be traced back to Emilio Pettoruti’s (Argentina, 1892–1971) early abstract works, which were in- spired by Futurism and produced in Italy during the second decade of the 20th century. Nev- ertheless, the two more widely recognized pioneers of abstraction are Joaquín Torres-García (Uruguay, 1874–1949) and Juan del Prete (Italy/Argentina, 1897–1987), and more recently Esteban Lisa (Spain/Argentina 1895–1983) for their abstract work in the 1930s. Modern abstract art in Latin America has been circumscribed between the early 1930s to the late 1970s in Argentina, Brazil, Uruguay and Venezuela, and in more recent years Colombia, Cuba and Mexico have also been incorporated into the historiography of abstraction. Fur- thermore, it is only recently that interest in exploring beyond geometric abstraction, to in- clude Informalist tendencies is beginning to emerge. Abstract art in Latin America developed through painting, sculpture, installation, architecture, printing techniques and photography, and it is characterized by its experimentalism, plurality, the challenging of canonical ideas re- lated to art, and particular ways of dialoguing, coexisting in tension or participation within the complex process of modernity—and modernization—in the context of the political regimes of the time. Certain complex and often contradictory forms of utopianism were pervasive in some of these abstract movements that have led to the creation of exhibitions with titles such as Geometry of Hope (The Blanton Museum of Art, Austin, 2007) or Inverted Utopias: Avant Garde Art in Latin America (The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, 2004). -

Flusseriana – an Intellectual Toolbox Siegfried Zielinski and Peter Weibel

Introduction Flusseriana – An Intellectual Toolbox Siegfried Zielinski and Peter Weibel inhalt_flusseriana_20150727-2.indd 4 27.07.15 13:34 “ The mystical has no rationale, is in permanent exile, wanders around, and is never at rest.”1 Amador Vega y Esquerra “[S]ynthetic images as an answer to Auschwitz”2 – the combative dialogician Vilém Flusser was very fond of pointed comments that would polarize. After making such a statement, which he often underlined with vigorous gestures and pathos, he would lean back contentedly in his chair for a moment and watch the reactions of the people he was talking to. Now he was quite sure that they would enter into a debate with him. For Flusser, proposition and objection generated ex- citement; not in order to arrive at a synthesis in the sense of Hegelian dialectics (Flusser was not a dialectical thinker), but to open a space for thought in which a rich fabric of arguments, positions, views, and even tricks and maneuvers could be spread out. There’s a lot behind the statement of Flusser’s quoted at the beginning of this text. Apart from the sheer provocation it represents, it can be interpreted as the most brutal summary of what occupied this intellectual from Prague in the diaspora, what he thought, wrote, and lived (in that order). The inconceivable event that was the Holocaust, understood by many of his intellectual Jewish fel- low sufferers as sacrosanct and untouchable and whose ontology ruled out the possibility of poetry for Theodor W. Adorno, is juxtaposed in this statement with a profane phenomenon. -

Agnes Martin Selected Bibliography Books

AGNES MARTIN SELECTED BIBLIOGRAPHY BOOKS AND EXHIBITION CATALOGUES 2019 Hannelore B. and Rudolph R. Schulhof Collection (exhibition catalogue). Text by Gražina Subelytė. Venice, Italy: Peggy Guggenheim Collection, 2019. 2018 Agnes Martin / Navajo Blankets (exhibition catalogue). Interview with Ann Lane Hedlund and Nancy Princenthal. New York: Pace Gallery, 2018. American Masters 1940–1980 (exhibition catalogue). Texts by Lucina Ward, James Lawrence and Anthony E Grudin. Canberra: National Gallery of Australia, 2018: 162–163, illustrated. An Eccentric View (exhibition catalogue). New York: Mignoni Gallery, 2018: illustrated. “Agnes Martin: Aus ihren Aufzeichnungen über Kunst.” In Küstlerinnen schreiben: Ausgewählte Beiträge zur Kunsttheorie aus drei Jahrhunderten. Edited by Renate Kroll and Susanne Gramatzki. Berlin: Dietrich Reimer Verlag GmbH, 2018: 183–187, illustrated. Ashton, Dore. “Dore Ashton on Agnes Martin.” In Fifty Years of Great Art Writing. London: Hayward Gallery Publishing, 2018: 53–61, illustrated. Agnes Martin: Selected Bibliography-Books and Exhibition Catalogs 2 Fritsch, Lena. “’Wenn ich an Kunst denke, denke ich an Schönheit’ – Agnes Martins Schriften.” In Küstlerinnen schreiben: Ausgewählte Beiträge zur Kunsttheorie aus drei Jahrhunderten. Edited by Renate Kroll and Susanne Gramatzki. Berlin: Dietrich Reimer Verlag GmbH, 2018: 188–197. Guerin, Frances. The Truth is Always Grey: A History of Modernist Painting. Minneapolis and London: University of Minnesota Press, 2018: plate 8, 9, illustrated. Intimate Infinite: Imagine a Journey (exhibition catalogue). New York: Lévy Gorvy, 2018: 100–101, illustrated. Martin, Henry. Agnes Martin: Pioneer, Painter, Icon. Tucson, Arizona: Schaffner Press, 2018. Martin, Agnes. “Agnes Martin: Old School.” In Auping, Michael. 40 Years: Just Talking About Art. Fort Worth, Texas and Munich: Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth; DelMonico Books·Prestel, 2018: 44–45, illustrated. -

Carlos Cruz-Diez

Alan Cristea Gallery Artist Biography 43 Pall Mall, London SW1Y 5JG +44 (0)20 7439 1866 [email protected] www.alancristea.com Carlos Cruz-Diez Born in Caracas in 1923, Carlos Cruz-Diez between 1940 to 1945 Diseño Carlos Cruz-Diez, Caracas, VE he studied art at the Escuela de Artes Plásticas y Aplicadas. In 2003 Cruz-Diez. Afiches. Exposición Homenaje a los 80 Años his earliest work, Cruz-Diez painted figurative canvases intended de Carlos Cruz-Diez, Museo de la Estampa y del Diseño to reflect and comment upon social issues. In 1954, influenced Carlos Cruz-Diez, Caracas, VE by his study of the Bauhaus and the European avant-garde, Cruz- 1999 Retrospectiva 1954-1998, Museo de Arte Moderno del Diez created his first abstract and interactive projects. In 1957 Zulia, Maracaibo, VE he began experimenting with colored light. In 1959 he became 1998 Cruz-Diez: El Color Autónomo, Museo de Arte Moderno interested in ‘the phyical dimension of colour. The following year, de Bogotá, CO Cruz-Diez and his family moved to Paris, where he met Argentine 1995 Reflexión sobre el Color, Museo Jacobo Borges, artist Luis Tomasello, and members of the Groupe de Recherche Caracas, Venezuela d’Art Visuel, and he quickly became an important member of the 1993 Apuntes sobre el Color, Museo de Bellas Artes, artistic communities there. Caracas, Venezuela 1992 Carlos Cruz-Diez La Visión del Color, Museo de Arte de In 1971, Cruz-Diez established his workshop on the rue Pierre Maracay, Maracay, Venezuela Sémard investigating experiences of color. The artist describes 1989 Realites de la Peinture, The Pushkin State Museum of his Chromosaturation series as the exploration of an often- Fine Arts, Moscow & Leningrad, Russia unnoticed reality: “That reality (which I consider visible) leads us Latin American Art, Hayward Gallery, London, UK; along other paths, both perceptive and sensory, to parallel ideas 1988 Carlos Cruz-Diez. -

The Responsive Eye by William C

The responsive eye By William C. Seitz. The Museum of Modern Art, New York, in collaboration with the City Art Museum of St. Louis [and others Author Museum of Modern Art (New York, N.Y.) Date 1965 Publisher [publisher not identified] Exhibition URL www.moma.org/calendar/exhibitions/2914 The Museum of Modern Art's exhibition history— from our founding in 1929 to the present—is available online. It includes exhibition catalogues, primary documents, installation views, and an index of participating artists. MoMA © 2017 The Museum of Modern Art MoMA 757 c.2 r//////////i LIBRARY Museumof ModernArt ARCHIVE wHgeugft. TheResponsive Eye BY WILLIAM C. SEITZ THE MUSEUM OF MODERN ART, NEW YORK IN COLLABORATION WITH THE CITY ART MUSEUM OF ST. LOUIS, THE CONTEMPORARY ART COUNCIL OF THE SEATTLE ART MUSEUM, THE PASADENA ART MUSEUM AND THE BALTIMORE MUSEUM OF ART /4/t z /w^- V TRUSTEES OF THE MUSEUM OF MODERN ART David Rockefeller, Chairman of the Board; Henry Allen Moe, Vice-Chairman;William S. Paley, Vice-Chairman; Mrs. Bliss Parkinson, Vice-Chairman;William A. M. Burden, President; James Thrall Soby, Vice-President;Ralph F. Colin, Vice-President;Gardner Cowles, Vice-President;Wa l ter Bareiss, Alfred H. Barr, Jr., *Mrs. Robert Woods Bliss, Willard C. Butcher, *Mrs. W. Murray Crane, John de Menil, Rene d'Harnoncourt, Mrs. C. Douglas Dillon, Mrs. Edsel B. Ford, *Mrs. Simon Guggenheim, Wallace K. Harrison, Mrs. Walter Hochschild, "James W. Husted, Philip Johnson, Mrs. Albert D. Lasker,John L. Loeb, Ranald H. Macdonald, Porter A. McCray, *Mrs. G. Macculloch Miller, Mrs. Charles S. -

Studio International

studio international 132 East 68th Street New York, NY 10065 Gego and Gerd Leufert: A Dialogue By Lilly Wei Febraury 2014 This exhibition of works by Gertrude Goldschmidt – Gego – and Gerd Leufert demonstrates their romance both with line and drawing and with one another Gertrude Goldschmidt (1912-94), better known as Gego, was born in Hamburg and studied architecture in Stuttgart. She left Germany in 1939 for South America. Gerd Leufert (1914-98) was born in Lithuania and studied graphic design in Hanover and Munich. He emigrated to South America in 1951. They met in Caracas in 1952 and remained Gerd Leufert. Listonado (Ventana) (Strip [Window]), 1972. Acrylic on wood, 35 together in Venezuela for the rest of their lives. While both had a strong 7/16 x 31 1/2 x 3 1/8 in (90 x 80 x 8 cm). Colección Patricia Phelps de Cisneros, influence on the direction that Latin American art took – in particular New York and Caracas. the geometric abstraction and kinetic art that flourished there from drawing (a forerunner of her later wire sculptures), Leufert both drew the 50s to the 70s – it is Gego who is now the more celebrated. on the paper and ripped it, actively engaging the support, to achieve comparable results in Shown together in this small gem of an exhibition at Hunter College, it is a circa 1973 work. a welcome addition to the growing number of exhibitions on modernist art from the region. Sensitively curated and installed by Geaninne Both were deeply interested in grids, as seen in two drawings from the Gutiérrez-Guimarães with Sarah Watson and Annie Wischmeyer, the same period. -

DONALD JUDD Born 1928 in Excelsior Springs, Missouri

This document was updated January 6, 2021. For reference only and not for purposes of publication. For more information, please contact the gallery. DONALD JUDD Born 1928 in Excelsior Springs, Missouri. Died 1994 in New York City. SOLO EXHIBITIONS 1957 Don Judd, Panoras Gallery, New York, NY, June 24 – July 6, 1957. 1963–1964 Don Judd, Green Gallery, New York, NY, December 17, 1963 – January 11, 1964. 1966 Don Judd, Leo Castelli Gallery, 4 East 77th Street, New York, NY, February 5 – March 2, 1966. Donald Judd Visiting Artist, Hopkins Center Art Galleries, Dartmouth College, Hanover, NH, July 16 – August 9, 1966. 1968 Don Judd, The Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, NY, February 26 – March 24, 1968 [catalogue]. Don Judd, Irving Blum Gallery, Los Angeles, CA, May 7 – June 1, 1968. 1969 Don Judd, Leo Castelli Gallery, 4 East 77th Street, New York, NY, January 4 – 25, 1969. Don Judd: Structures, Galerie Ileana Sonnabend, Paris, France, May 6 – 29, 1969. New Works, Galerie Bischofberger, Zürich, Switzerland, May – June 1969. Don Judd, Galerie Rudolf Zwirner, Cologne, Germany, June 4 – 30, 1969. Donald Judd, Irving Blum Gallery, Los Angeles, CA, September 16 – November 1, 1969. 1970 Don Judd, Stedelijk Van Abbemuseum, Eindhoven, The Netherlands, January 16 – March 1, 1970; traveled to Folkwang Museum, Essen, Germany, April 11 – May 10, 1970; Kunstverein Hannover, Germany, June 20 – August 2, 1970; and Whitechapel Art Gallery, London, United Kingdom, September 29 – November 1, 1970 [catalogue]. Don Judd, The Helman Gallery, St. Louis, MO, April 3 – 29, 1970. Don Judd, Leo Castelli Gallery, 4 East 77th Street, and 108th Street Warehouse, New York, NY, April 11 – May 9, 1970. -

Colombian Artists in Paris, 1865-1905

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 2010 Colombian Artists in Paris, 1865-1905 Maya Jiménez The Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/2151 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] COLOMBIAN ARTISTS IN PARIS, 1865-1905 by MAYA A. JIMÉNEZ A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Art History in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, The City University of New York 2010 © 2010 MAYA A. JIMÉNEZ All Rights Reserved ii This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in Art History in satisfaction of the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Professor Katherine Manthorne____ _______________ _____________________________ Date Chair of Examining Committee Professor Kevin Murphy__________ ______________ _____________________________ Date Executive Officer _______Professor Judy Sund________ ______Professor Edward J. Sullivan_____ ______Professor Emerita Sally Webster_______ Supervisory Committee THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iii ABSTRACT Colombian Artists in Paris, 1865-1905 by Maya A. Jiménez Adviser: Professor Katherine Manthorne This dissertation brings together a group of artists not previously studied collectively, within the broader context of both Colombian and Latin American artists in Paris. Taking into account their conditions of travel, as well as the precarious political and economic situation of Colombia at the turn of the twentieth century, this investigation exposes the ways in which government, politics and religion influenced the stylistic and thematic choices made by these artists abroad. -

Mira Schendel : Six Drawings - Monotipias, Toquinhos 26 February – 30 April 2021

Press Release Mira Schendel : Six drawings - Monotipias, Toquinhos 26 February – 30 April 2021 Installation view of Monotipias [Monotypes] Cecilia Brunson Projects presents Mira Schendel: Six drawings - Monotipias, Toquinhos. Schendel was born in Zurich in 1919. She was studying philosophy and art in Milan in the late 1930s when Mussolini’s racial laws were announced. Schendel was raised as a Catholic in Italy but due to her family’s Jewish heritage she was stripped of her citizenship and forced to leave the country. Having moved around Europe, among currents of anti-Semitic persecution, Schendel managed to reach Sarajevo where she lived throughout the Second World War. In 1949 she moved to Brazil, settling in São Paulo in 1953. After years of displacement, she began to establish herself as an artist in Brazil’s vibrant, post-war cultural climate. Two of the works in this selection are from Schendel’s expansive series of Monotipias [Monotypes]. In the creation of this series the material dictated the method; Schendel was given some Japanese rice paper but struggled to utilise it without it tearing. Eventually she came up with a solution: she laid the rice paper over oiled glass and scratched with a point or fingernail, causing the oil to adhere to the paper. Schendel referred to this series as dealing with the ‘problem of transparency’ and exhibits her fascination with the meeting of opacity and translucency. The oil and the paper were brought into contact and then her touch Installation view of Toquinhos [Little Stubs] dictated the flow of the lines that interrupted the transparency of the paper. -

Gego, Between Transparency and the Invisible April 21 – July 21, 2007

The Drawing Center For Immediate Release For further information, please contact Lisa Gold, 212-219-2166, ext. 214 [email protected] The Drawing Center announces Gego, Between Transparency and the Invisible April 21 – July 21, 2007 Opening Reception: Friday, April 20, 6 – 8 pm Gallery Talk: Saturday, April 21, 4 pm Main Gallery, 35 Wooster Street New York, March 15, 2007 – From April 21 through July 21, The Drawing Center will present Gego, Between Transparency and the Invisible, a groundbreaking exhibition that explores the intriguing relationship between light and line in the work of German born, Venezuelan artist Gego (Gertrud Goldschmidt, 1912-1994). Largely unknown to mainstream U.S. audiences, Gego is considered by many scholars to be one of the most innovative artists of the second half of the 20th century. Organized by the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, the exhibition traces the development of the artist’s concern with trans- parent depth, featuring a rarely seen series of monotypes of the early 1950s, delicate “drawings without paper” of the late 1970s - 1980s, and an example from one of her most celebrated and representative series: the Reticulárea. Gego, Between Transparency and the Invisible is curated by Mari Carmen Ramírez, Wortham Curator of Latin American Art at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston. Juxtaposing important artworks produced from the mid- 1950s to the late 1980s and bringing two bodies of Gego's work into dialogue for the first time, Gego, Between Transparency and the Invisible will foreground the critical role that drawing played in the artist's oeuvre. On view will be nearly 60 artworks which include ink drawings, three-dimensional structures, watercolors, artist books, and tejeduras.