Exhibiting Scenographic Identities at the 2007 & 2011

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

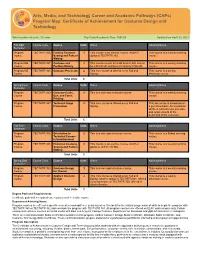

Program Map: Certificate of Achievement for Costume Design and Technology

Arts, Media, and Technology Career and Academic Pathways (CAPs) Program Map: Certificate of Achievement for Costume Design and Technology Total number of units: 23 units Top Code/Academic Plan: 1006.00 Updated on April 25, 2021 Fall Odd Course Code Course Units Notes Advising Notes Semester Program TECTHTR 366 Fantasy Costume 3 This course is an elective course. Another This course is a weekly morning Course Sewing and Pattern option is TECTHTR 365. course. Making Program/GE TECTHTR 367 Costume and 3 This course counts as a GE Area C Arts course This course is a weekly morning Course Fashion History for LACCD GE and Area C1 Arts for CSU GE. course. Program/GE TECTHTR 345 Costume Practicum 2 This core course is offered every Fall and This course is a weekly Course Spring. afternoon course. Total Units 8 Spring Even Course Code Course Units Notes Advising Notes Semester Program TECTHTR 363 Costume Crafts, 3 This is a core and milestone course. This course is a weekly morning Course Dye, and Fabric course. Printing Program TECTHTR 342 Technical Stage 2 This core course is offered every Fall and This lab course is scheduled on Course Production Spring. a per show basis. An orientation will be held to discuss schedule and requirements at the beginning of the semester. Total Units 5 Fall Even Course Code Course Units Notes Advising Notes Semester Program TECTHTR 305 Orientation to 2 This is a core and milestone course. This course is a Friday morning Course Technical Careers course. in Entertainment Program TECTHTR 365 Historical Costume 3 This course is an elective course. -

1895 a Landmark in Cricket History

Thursday 28 February, page 4: CRICKET The annual meeting of the Nottinghamshire County Cricket Club was held at the George Hotel, Nottingham, yesterday, when Mr W E Denison presided over a very large number of members. In the report and accounts there was small measure for gratification. Insignificant “gates” were the rule all through last summer, and the only three-figure sum taken at any one match was £253 in the case of Notts v Surrey. There was a loss on the year’s working and the sum due to the bankers had risen from £4,628 to £4,845. This year’s programme was announced, the matches being with Sussex, Surrey, Kent, Middlesex, Gloucestershire, Yorkshire, Lancashire and Derbyshire, the last-mentioned taking the place of Somerset. Flowers will receive as a benefit the proceeds of Lancashire v Notts. The report and accounts were adopted. Lord Henry Cavendish Bentinck was elected president for the year, with the Mayor of Nottingham as vice-president, while Mr W E Denison, Captain Tomasson and Mr J A Dixon were elected on to the committee. It was stated that every effort would be used to increase the membership of the club; while Mr Denison, in addressing the meeting, said that he thought the popularity of other sports had something to do with the decrease in attendances; it was not wholly the fault of the slow cricket with which Nottingham had been charged. 1 Friday 12 April, page 8: THE COMING CRICKET SEASON Two important changes will make the season of 1895 a landmark in cricket history. -

American New Wave

Newsletter April 2021 SPOTLIGHT AMERICAN NEW WAVE IN THE SUMMER OF 2021, THE SCENOGRAPHER BEGINS ITS FIRST ‘OVERSEAS JOURNEY’ TO DISCOVER DESIGN FOR LIVE PERFORMANCE BY YOUNG CREATIVES FROM THE 1980S TO THE PRESENT DAY. FOR THE FIRST TIME, A EUROPEAN THEATRE MAGAZINE IS ENDEAVOURING TO GIVE AMPLE SPACE TO YOUNG AMERICAN DIRECTORS, SET AND COSTUME DESIGNERS WHO ARE AMONG THE MOST REPRESENTATIVE ON THE THEATRE SCENE AND WHO HAVE MADE – OR ARE MAKING - A NAME FOR THEMSELVES AT THE TURN OF THIS CENTURY. A BROAD-BASED PANORAMA OF THE VITALITY AND ORIGINALITY OF THEATRE IN THE UNITED STATES, A MULTICULTURAL GALAXY MADE UP OF A DIVERSITY OF ETHNIC INFLUENCES WILL TAKE SHAPE. The prestigious selection includes includes the following authors: BEOWULF BORITT (Set and Costume Designer); THADDEUS STRASSBERGER (Director and Set Designer); WILSON CHIN (Set Designer); ARNULFO MALDONADO (Set and Costume Designer), DAVID CHACON PEREZ (Director and Set Designer); ALEX TIMBERS (Director and Writer). BEOWULF BORITT is a New York City-based scenic designer for theater. He is known for his Tony Award winning design for the play Act One in 2014 (This issue is the first in the collection. It is already available in both digital & print editions.). Read more: https://www.thescenographer.org/boritt-beowulf/ THADDEUS STRASSBERGER is an American and citizen of the Cherokee Nation opera director and scenic designer. In 2005 he was awarded the European Opera Directing Prize by Opera Europa for his work on Opera Ireland’s production of Rossini’s La Cenerentola. WILSON CHIN is an award-winning production designer and producer from Redwood City, CA and based in New York City. -

Scenography Studies – on the Margin of Art History and Theater Studies

Art Inquiry. Recherches sur les arts 2014, vol. XVI ISSN 1641-9278 Dominika Łarionow Department of Art History, University of Łódź [email protected] SCENOGRAPHY STUDIES – ON THE MARGIN OF ART HISTORY AND THEATER STUDIES Abstract: Scenography as a domain of artistic activity has always been a liminal art, placed between the visual arts and theater, with the latter being treated as a chiefly literary domain. The history of scenography to date has recorded two moments when it rose to prominence, becoming the “queen” of the spectacle: the Renaissance and modern times. The article will briefly discuss its history, to show the main reasons for the exclusion of scenography from the domain of academic research. The author will survey some recent publications on set design written by practitioners and academics. Keywords: set design – scenography – history of theater – theater. Scenography as a domain of artistic activity has always been a liminal art, placed between the visual arts and theater, with the latter being treated as a chiefly literary domain. Its roots reach back to the theater of ancient Greece. Even during that period, it was already a marginalized discipline. Aristotle noted in his Poetics, which can be partly regarded as representative for the ideas of his time, that although a spectacle is the work of the skenograph, its significance depends on the craftsmanship of the playwright. Therefore, he acknowledges the quality that scenography contributes to the spectacle, but in order to achieve catharsis, that ancient category associated with the reception of a work of art, a work of great literary value is needed. -

GRAPHIC DESIGNER [email protected] +1(347)636.6681 AWARDS + HONORS SKILLS ASHLEY LAW EDUCATION WORK EXPERIENCE UNIQLO GLOBAL

ASHLEY LAW GRAPHIC DESIGNER [email protected] http://ashleylaw.info +1(347)636.6681 linkedin.com/in/ashley-law instagram.com/_ashleylaw EDUCATION AWA RDS SKILLS SCHOOL OF VISUAL + GRAPHIS (GOLD) SOFTWARE ARTS (New York) NEW TALENT ANNUAL InDesign HONORS BFA Design Editorial Design “Zine”- Illustrator 2017–2019 2018 Photoshop PremierePro AfterEffects SCHOOL OF THE SVA HONOR’S LIST Sketch ART INSTITUTE OF 2017–2018 CHICAGO (Chicago) Fine Art + Visual CAPABILITIES & Critical Studies SAIC MERIT Branding 2013–2015 SCHOLARSHIP Content Production 2013–2015 Identity System Interactive/Digital Design Print + Editorial Design Typography WORK EXPERIENCE UNIQLO GLOBAL Junior Graphic Design for the GCL team focusing on CREATIVE LAB Designer creative direction of special projects, 06. 2019 - Present (New York) under the direction of Shu Hung and John Jay. Campaigns include collaborations (i.e. Lemaire, JW Anderson, Alexander Wang) and new store openings. MATTE PROJECTS Design Intern Designing client proposals, print, 01. 2019–04. 2019 (New York) digital & social collateral for marketing agency. Worked on projects for Cartier, The Chainsmokers, Moda Operandi & MATTE events (FNT, BLACK-NYC, Full Moon Festival, La Luna). PYT OPERANDI Creative Project Associate for artist management & creative 03–06. 2016 Associate project development company with emphasis (Hong Kong) in film, photography, exhibitions, project & business development consulting. CLOVER GROUP Intimates Design Designed for leading global manufacturer INTL LIMITED. Intern of intimate apparel, emphasis on the 08–10. 2015 (Hong Kong) Victoria’s Secret account. Visually detailed creative direction, identity & design of project pitches. Similar work for clients including Wacoal, Aerie, Lane Bryant. GIORGIO ARMANI Menswear R&D Shadowed Manager of R&D department OPERATIONS Intern for Menswear at HK Armani Corporate 06–09. -

Costume Design ©2019 Educational Theatre Association

For internal use only Costume Design ©2019 Educational Theatre Association. All rights reserved. Student(s): School: Selection: Troupe: 4 | Superior 3 | Excellent 2 | Good 1 | Fair SKILLS Above standard At standard Near standard Aspiring to standard SCORE Job Understanding Articulates a broad Articulates an Articulates a partial Articulates little and Interview understanding of the understanding of the understanding of the understanding of the Articulation of the costume costume designer’s role costume designer’s role costume designer’s role costume designer’s role designer’s role and specific and job responsibilities; and job responsibilities; and job responsibilities; and job responsibilities; job responsibilities; thoroughly presents adequately presents and inconsistently presents does not explain an presentation and and explains the explains the executed and explains the executed executed design, creative explanation of the executed executed design, creative design, creative decisions, design, creative decisions decisions or collaborative design, creative decisions, decisions, and and collaborative process. and/or collaborative process. and collaborative process. collaborative process. process. Comment: Design, Research, A well-conceived set of Costume designs, Incomplete costume The costume designs, and Analysis costume designs, research, and script designs, research, and research, and analysis Design, research and detailed research, and analysis address the script analysis of the script do not analysis addresses the thorough script artistic and practical somewhat address the address the artistic and artistic and practical needs analysis clearly address needs of the production artistic and practical practical needs of the (given circumstances) of the artistic and practical and support the unifying needs of the production production or support the the script to support the needs of production and concept. -

Lighting Lighting

PHX CDM ELLIPSOIDAL ELLIPSOIDAL LIGHTING The PHX CDM 5°, 10°, 19°, 26°, 36° and 50° fxed focus Catalog Numbers ellipsoidals are truly state of the art luminaires in style, PHXC-5-* versatility of functions and efciency. Confgured with a PHXC-10-* 39W, 70W, or 150W ballast, these lighting fxtures with their PHXC-19-* respective Ceramic Discharge Metal Halide Lamps will direct PHXC-26-* bright,sharp or soft-edged illumination to their subject. PHXC-36-* PHXC-50-* Each unit has two accessory slots and two accessory holders on the lens barrel. The slot nearest to the lamp is specifcally sized to accept pattern holders for metal gobos with 25⁄8“ image diameters (“B”size). The second slot, which has a cover to eliminate light leaks when not in use, will accept either a glass pattern holder, drop-in iris, gobo rotator or a dual gobo rotator. Both the 5° and the 10° PHX CDM units have generous sized front accessory holders with self-closing and self-latching safety retainers. These accessory holders are large enough for color frames, glass color frames,donuts, snoots or color changers and combinations of accessories as required. The 19°, 26°, 36°, and 50° fxed focus units have accessory holders with two separate channels. The lens barrels are interchangeable without the use of tools. These low wattage, long lamp life units produce a cool light with a high color rendering index that will not seriously impact ambient temperatures. Ideally suited for projecting company logos, spot lighting and enhancing physical logos 39/70/150 WATT and signs or lighting trade show booths, products and PHX ELLIPSOIDAL goods. -

C U R R I C U L U M G U I

C U R R I C U L U M G U I D E NOV. 20, 2018–MARCH 3, 2019 GRADES 9 – 12 Inside cover: From left to right: Jenny Beavan design for Drew Barrymore in Ever After, 1998; Costume design by Jenny Beavan for Anjelica Huston in Ever After, 1998. See pages 14–15 for image credits. ABOUT THE EXHIBITION SCAD FASH Museum of Fashion + Film presents Cinematic The garments in this exhibition come from the more than Couture, an exhibition focusing on the art of costume 100,000 costumes and accessories created by the British design through the lens of movies and popular culture. costumer Cosprop. Founded in 1965 by award-winning More than 50 costumes created by the world-renowned costume designer John Bright, the company specializes London firm Cosprop deliver an intimate look at garments in costumes for film, television and theater, and employs a and millinery that set the scene, provide personality to staff of 40 experts in designing, tailoring, cutting, fitting, characters and establish authenticity in period pictures. millinery, jewelry-making and repair, dyeing and printing. Cosprop maintains an extensive library of original garments The films represented in the exhibition depict five centuries used as source material, ensuring that all productions are of history, drama, comedy and adventure through period historically accurate. costumes worn by stars such as Meryl Streep, Colin Firth, Drew Barrymore, Keira Knightley, Nicole Kidman and Kate Since 1987, when the Academy Award for Best Costume Winslet. Cinematic Couture showcases costumes from 24 Design was awarded to Bright and fellow costume designer acclaimed motion pictures, including Academy Award winners Jenny Beavan for A Room with a View, the company has and nominees Titanic, Sense and Sensibility, Out of Africa, The supplied costumes for 61 nominated films. -

ANDREA BECHERT Scenic Designer / Scenographer

ANDREA BECHERT USA local 829 SCENIC DESIGNER / SCENOGRAPHER 1116 E. 46th Street, #2W, Chicago, IL 60653 * cell phone: 650-533-6059 * email: [email protected] Website: WWW.SCORPIONDESIGNS.NET CURRENT PROJECTS TheatreWorks The Country House (director: Robert Kelley – opens August, 2015) Palo Alto, CA Douglas Morrison Theatre By the Way, Meet Vera Stark (director: Dawn Monique Williams – Hayward, CA opens August, 2015) Center Repertory Theatre Vanya & Sonia & Masha & Spike (director: Mark Phillips – opens October, 2015) Walnut Creek, CA University of Michigan American Idiot (director: Linda Goodrich – opens October, 2015) Ann Arbor, MI RECENT PROJECTS TheatreWorks Sweeney Todd (director Robert Kelley - October 2014) Palo Alto, CA The Starlight Theatre Mary Poppins (director: Michael Webb - June, 2015) Rockford, Illinois The Last Five years (director: Michael Webb - June, 2015) Memphis (director: Michael Webb - June, 2015) Young Frankenstein (director: Michael Webb - June, 2015) University of Miami Faculty, Scenic Designer, and Scenic Artist (Fall semester, 2014) Served as Scenic Designer for a new production of Carmen, written and directed by Moises Kaufman, in collaboration with Techtonic Theatre Company 25th Annual Putnam County Spelling Bee (director: Greg Brown – Sept. 2014) Courses taught: Drawing for the Theatre History of Decor ILLUSTRATIVE LIST OF SCENIC DESIGNS (FULL LIST PROVIDED UPON REQUEST – OVER 300) TheatreWorks 28 productions between 1997 - 2015, including: Palo Alto, California Sweeney Todd (director Robert Kelley -

A GLOSSARY of THEATRE TERMS © Peter D

A GLOSSARY OF THEATRE TERMS © Peter D. Lathan 1996-1999 http://www.schoolshows.demon.co.uk/resources/technical/gloss1.htm Above the title In advertisements, when the performer's name appears before the title of the show or play. Reserved for the big stars! Amplifier Sound term. A piece of equipment which ampilifies or increases the sound captured by a microphone or replayed from record, CD or tape. Each loudspeaker needs a separate amplifier. Apron In a traditional theatre, the part of the stage which projects in front of the curtain. In many theatres this can be extended, sometimes by building out over the pit (qv). Assistant Director Assists the Director (qv) by taking notes on all moves and other decisions and keeping them together in one copy of the script (the Prompt Copy (qv)). In some companies this is done by the Stage Manager (qv), because there is no assistant. Assistant Stage Manager (ASM) Another name for stage crew (usually, in the professional theatre, also an understudy for one of the minor roles who is, in turn, also understudying a major role). The lowest rung on the professional theatre ladder. Auditorium The part of the theatre in which the audience sits. Also known as the House. Backing Flat A flat (qv) which stands behind a window or door in the set (qv). Banjo Not the musical instrument! A rail along which a curtain runs. Bar An aluminium pipe suspended over the stage on which lanterns are hung. Also the place where you will find actors after the show - the stage crew will still be working! Barn Door An arrangement of four metal leaves placed in front of the lenses of certain kinds of spotlight to control the shape of the light beam. -

Chapter 10: Stage Settings

396-445 CH10-861627 12/4/03 11:11 PM Page 396 CHAPTER ᪴ ᪴ ᪴ ᪴ ᪴ ᪴ ᪴ ᪴ ᪴ ᪴ 10 Stage Settings Stage settings establish a play’s atmosphere. In Andrew Lloyd Webber’s Sunset Boulevard, shown here, the charac- ters are dwarfed by the imposing paneled room that includes a sweep- ing staircase. he theater, for all its artifices, depicts life Tin a sense more truly than history. —GEORGE SANTAYANA, POET AND PHILOSOPHER 396 396-445 CH10-861627 12/4/03 11:12 PM Page 397 SETTING THE SCENE Focus Questions What are the purposes of scenery in a play? What are the effects of scenery in a play? How has scenic design developed from the Renaissance through modern times? What are some types of sets? What are some of the basic principles and considerations of set design? How do you construct and erect a set? How do you paint and build scenery? How do you shift and set scenery? What are some tips for backstage safety? Vocabulary box set curtain set value unit set unity tints permanent set emphasis shades screens proportion intensity profile set balance saturation prisms or periaktoi hue A thorough study of the theater must include developing appreciation of stage settings and knowledge of how they are designed and constructed. Through the years, audiences have come to expect scenery that not only presents a specific locale effectively but also adds an essential dimension to the production in terms of detail, mood, and atmosphere. Scenery and lighting definitely have become an integral part of contemporary play writ- ing and production. -

Stage Lighting Technician Handbook

The Stage Lighting Technician’s Handbook A compilation of general knowledge and tricks of the lighting trade Compiled by Freelancers in the entertainment lighting industry The Stage Lighting Technician's Handbook Stage Terminology: Learning Objectives/Outcomes. Understanding directions given in context as to where a job or piece of equipment is to be located. Applying these terms in conjunction with other disciplines to perform the work as directed. Lighting Terms: Learning Objectives/Outcome Learning the descriptive terms used in the use and handling of different types of lighting equipment. Applying these terms, as to the location and types of equipment a stagehand is expected to handle. Electrical Safety: Learning Objectives/Outcomes. Learning about the hazards, when one works with electricity. Applying basic safety ideas, to mitigate ones exposure to them in the field. Electricity: Learning Objectives/Outcomes. Learning the basic concepts of what electricity is and its components. To facilitate ones ability to perform the mathematics to compute loads, wattages and the like in order to safely assemble, determine electrical needs and solve problems. Lighting Equipment Learning Objectives/Outcomes. Recognize the different types of lighting equipment, use’s and proper handling. Gain basic trouble shooting skills to successfully complete a task. Build a basic understanding of applying these skills in the different venues that we work in to competently complete assigned tasks. On-sight Lighting Techniques Learning Objectives/Outcomes. Combing the technical knowledge previously gained to execute lighting request while on site, whether in a ballroom or theatre. Approaches, to lighting a presentation to aspects of theatrical lighting to meet a client’s expectations.