Hong Kong, China: the Border As Palimpsest (DENISE Y

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hong Kong Final Report

Urban Displacement Project Hong Kong Final Report Meg Heisler, Colleen Monahan, Luke Zhang, and Yuquan Zhou Table of Contents Executive Summary 5 Research Questions 5 Outline 5 Key Findings 6 Final Thoughts 7 Introduction 8 Research Questions 8 Outline 8 Background 10 Figure 1: Map of Hong Kong 10 Figure 2: Birthplaces of Hong Kong residents, 2001, 2006, 2011, 2016 11 Land Governance and Taxation 11 Economic Conditions and Entrenched Inequality 12 Figure 3: Median monthly domestic household income at LSBG level, 2016 13 Figure 4: Median rent to income ratio at LSBG level, 2016 13 Planning Agencies 14 Housing Policy, Types, and Conditions 15 Figure 5: Occupied quarters by type, 2001, 2006, 2011, 2016 16 Figure 6: Domestic households by housing tenure, 2001, 2006, 2011, 2016 16 Public Housing 17 Figure 7: Change in public rental housing at TPU level, 2001-2016 18 Private Housing 18 Figure 8: Change in private housing at TPU level, 2001-2016 19 Informal Housing 19 Figure 9: Rooftop housing, subdivided housing and cage housing in Hong Kong 20 The Gentrification Debate 20 Methodology 22 Urban Displacement Project: Hong Kong | 1 Quantitative Analysis 22 Data Sources 22 Table 1: List of Data Sources 22 Typologies 23 Table 2: Typologies, 2001-2016 24 Sensitivity Analysis 24 Figures 10 and 11: 75% and 25% Criteria Thresholds vs. 70% and 30% Thresholds 25 Interviews 25 Quantitative Findings 26 Figure 12: Population change at TPU level, 2001-2016 26 Figure 13: Change in low-income households at TPU Level, 2001-2016 27 Typologies 27 Figure 14: Map of Typologies, 2001-2016 28 Table 3: Table of Draft Typologies, 2001-2016 28 Typology Limitations 29 Interview Findings 30 The Gentrification Debate 30 Land Scarcity 31 Figures 15 and 16: Google Earth Images of Wan Chai, Dec. -

Icons, Culture and Collective Identity of Postwar Hong Kong

Intercultural Communication Studies XXII: 1 (2013) R. MAK & C. CHAN Icons, Culture and Collective Identity of Postwar Hong Kong Ricardo K. S. MAK & Catherine S. CHAN Hong Kong Baptist University, Hong Kong S.A.R., China Abstract: Icons, which take the form of images, artifacts, landmarks, or fictional figures, represent mounds of meaning stuck in the collective unconsciousness of different communities. Icons are shortcuts to values, identity or feelings that their users collectively share and treasure. Through the concrete identification and analysis of icons of post-war Hong Kong, this paper attempts to highlight not only Hong Kong people’s changing collective needs and mental or material hunger, but also their continuous search for identity. Keywords: Icons, Hong Kong, Hong Kong Chinese, 1997, values, identity, lifestyle, business, popular culture, fusion, hybridity, colonialism, economic takeoff, consumerism, show business 1. Introduction: Telling Hong Kong’s Story through Icons It seems easy to tell the story of post-war Hong Kong. If merely delineating the sky-high synopsis of the city, the ups and downs, high highs and low lows are at once evidently remarkable: a collective struggle for survival in the post-war years, tremendous social instability in the 1960s, industrial take-off in the 1970s, a growth in economic confidence and cultural arrogance in the 1980s and a rich cultural upheaval in search of locality before the handover. The early 21st century might as well sum up the development of Hong Kong, whose history is long yet surprisingly short- propelled by capitalism, gnawing away at globalization and living off its elastic schizophrenia. -

The Guangzhou-Hongkong Strike, 1925-1926

The Guangzhou-Hongkong Strike, 1925-1926 Hongkong Workers in an Anti-Imperialist Movement Robert JamesHorrocks Submitted in accordancewith the requirementsfor the degreeof PhD The University of Leeds Departmentof East Asian Studies October 1994 The candidateconfirms that the work submitted is his own and that appropriate credit has been given where referencehas been made to the work of others. 11 Abstract In this thesis, I study the Guangzhou-Hongkong strike of 1925-1926. My analysis differs from past studies' suggestions that the strike was a libertarian eruption of mass protest against British imperialism and the Hongkong Government, which, according to these studies, exploited and oppressed Chinese in Guangdong and Hongkong. I argue that a political party, the CCP, led, organised, and nurtured the strike. It centralised political power in its hands and tried to impose its revolutionary visions on those under its control. First, I describe how foreign trade enriched many people outside the state. I go on to describe how Chinese-run institutions governed Hongkong's increasingly settled non-elite Chinese population. I reject ideas that Hongkong's mixed-class unions exploited workers and suggest that revolutionaries failed to transform Hongkong society either before or during the strike. My thesis shows that the strike bureaucracy was an authoritarian power structure; the strike's unprecedented political demands reflected the CCP's revolutionary political platform, which was sometimes incompatible with the interests of Hongkong's unions. I suggestthat the revolutionary elite's goals were not identical to those of the unions it claimed to represent: Hongkong unions preserved their autonomy in the face of revolutionaries' attempts to control Hongkong workers. -

ICC – Rising High for the Future of Hong Kong 3. Conference

ctbuh.org/papers Title: ICC – Rising High for the Future of Hong Kong Author: Tony Tang, Architect and Project Director of ICC, Sun Hung Kai Properties Limited Subjects: Architectural/Design Building Case Study Keywords: Building Management Connectivity Construction Design Process Façade Fire Safety Mixed-Use Passive Design Urban Planning Vertical Transportation Publication Date: 2016 Original Publication: Cities to Megacities: Shaping Dense Vertical Urbanism Paper Type: 1. Book chapter/Part chapter 2. Journal paper 3. Conference proceeding 4. Unpublished conference paper 5. Magazine article 6. Unpublished © Council on Tall Buildings and Urban Habitat / Tony Tang ICC – Rising High for the Future of Hong Kong 环球贸易广场——香港未来新高度 Abstract | 摘要 Tony Tang Architect and Project Director of ICC | ICC建筑师和项目总监 Standing at 484 meters, Sun Hung Kai’s ICC is the tallest building in Hong Kong and currently the Sun Hung Kai Properties Limited 7th tallest in the world. ICC does not only add to the stock of the tall buildings in Hong Kong, it 新鸿基地产发展有限公司 also helps to transform the once barren West Kowloon district into a new business, cultural and Bangkok, Thailand transportation hub of Hong Kong. The building and its associated amenities have been planned 曼谷,泰国 and developed over a decade-long period. This has shown a careful master planning and Tony Tang graduated from The University of Hong Kong and has since practiced architecture and project management for collaborative execution among the developer, architect, engineers and facility managers. This over 25 years. Mr. Tang has participated in a number of major paper details the history, the concept and design of ICC as well as how the continuous devoted commercial and composite development projects in Hong Kong, Shanghai, Guangzhou, and Beijing. -

Modern Hong Kong

Modern Hong Kong Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Asian History Modern Hong Kong Steve Tsang Subject: China, Hong Kong, Macao, and/or Taiwan Online Publication Date: Feb 2017 DOI: 10.1093/acrefore/9780190277727.013.280 Abstract and Keywords Hong Kong entered its modern era when it became a British overseas territory in 1841. In its early years as a Crown Colony, it suffered from corruption and racial segregation but grew rapidly as a free port that supported trade with China. It took about two decades before Hong Kong established a genuinely independent judiciary and introduced the Cadet Scheme to select and train senior officials, which dramatically improved the quality of governance. Until the Pacific War (1941–1945), the colonial government focused its attention and resources on the small expatriate community and largely left the overwhelming majority of the population, the Chinese community, to manage themselves, through voluntary organizations such as the Tung Wah Group of Hospitals. The 1940s was a watershed decade in Hong Kong’s history. The fall of Hong Kong and other European colonies to the Japanese at the start of the Pacific War shattered the myth of the superiority of white men and the invincibility of the British Empire. When the war ended the British realized that they could not restore the status quo ante. They thus put an end to racial segregation, removed the glass ceiling that prevented a Chinese person from becoming a Cadet or Administrative Officer or rising to become the Senior Member of the Legislative or the Executive Council, and looked into the possibility of introducing municipal self-government. -

The RTHK Coverage of the 2004 Legislative Council Election Compared with the Commercial Broadcaster

Mainstream or Alternative? The RTHK Coverage of the 2004 Legislative Council Election Compared with the Commercial Broadcaster so Ming Hang A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Philosophy in Government and Public Administration © The Chinese University of Hong Kong June 2005 The Chinese University of Hong Kong holds the copyright of this thesis. Any person(s) intending to use a part or whole of the materials in the thesis in a proposed publication must seek copyright release from the Dean of the Graduate School. 卜二,A館書圆^^ m 18 1 KK j|| Abstract Theoretically, public broadcaster and commercial broadcaster are set up and run by two different mechanisms. Commercial broadcaster, as a proprietary organization, is believed to emphasize on maximizing the profit while the public broadcaster, without commercial considerations, is usually expected to achieve some objectives or goals instead of making profits. Therefore, the contribution by public broadcaster to the society is usually expected to be different from those by commercial broadcaster. However, the public broadcasters are in crisis around the world because of their unclear role in actual practice. Many politicians claim that they cannot find any difference between the public broadcasters and the commercial broadcasters and thus they asserted to cut the budget of public broadcasters or even privatize all public broadcasters. Having this unstable situation of the public broadcasting, the role or performance of the public broadcasters in actual practice has drawn much attention from both policy-makers and scholars. Empirical studies are divergent on whether there is difference between public and commercial broadcaster in actual practice. -

Discourse, Social Scales, and Epiphenomenality of Language Policy: a Case Study of a Local, Hong Kong NGO

Discourse, Social Scales, and Epiphenomenality of Language Policy: A Case Study of a Local, Hong Kong NGO Item Type text; Electronic Dissertation Authors Tso, Elizabeth Ann Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 27/09/2021 12:25:43 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/623063 DISCOURSE, SOCIAL SCALES, AND EPIPHENOMENALITY OF LANGUAGE POLICY: A CASE STUDY OF A LOCAL, HONG KONG NGO by Elizabeth Ann Tso __________________________ Copyright © Elizabeth Ann Tso 2017 A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the GRADUATE INTERDISCIPLINARY PROGRAM IN SECOND LANGUAGE ACQUISITION AND TEACHING In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 2017 2 THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA GRADUATE COLLEGE As members of the Dissertation Committee, we certify that we have read the dissertation prepared by Elizabeth Tso, titled Discourse, Social Scales, and Epiphenomenality of Language Policy: A Case Study of a Local, Hong Kong NGO, and recommend that it be accepted as fulfilling the dissertation requirement for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy. _______________________________________________ Date: (January 13, 2017) Perry Gilmore _______________________________________________ Date: (January 13, 2017) Wenhao Diao _______________________________________________ Date: (January 13, 2017) Sheilah Nicholas Final approval and acceptance of this dissertation is contingent upon the candidate’s submission of the final copies of the dissertation to the Graduate College. -

The Globalization of Chinese Food ANTHROPOLOGY of ASIA SERIES Series Editor: Grant Evans, University Ofhong Kong

The Globalization of Chinese Food ANTHROPOLOGY OF ASIA SERIES Series Editor: Grant Evans, University ofHong Kong Asia today is one ofthe most dynamic regions ofthe world. The previously predominant image of 'timeless peasants' has given way to the image of fast-paced business people, mass consumerism and high-rise urban conglomerations. Yet much discourse remains entrenched in the polarities of 'East vs. West', 'Tradition vs. Change'. This series hopes to provide a forum for anthropological studies which break with such polarities. It will publish titles dealing with cosmopolitanism, cultural identity, representa tions, arts and performance. The complexities of urban Asia, its elites, its political rituals, and its families will also be explored. Dangerous Blood, Refined Souls Death Rituals among the Chinese in Singapore Tong Chee Kiong Folk Art Potters ofJapan Beyond an Anthropology of Aesthetics Brian Moeran Hong Kong The Anthropology of a Chinese Metropolis Edited by Grant Evans and Maria Tam Anthropology and Colonialism in Asia and Oceania Jan van Bremen and Akitoshi Shimizu Japanese Bosses, Chinese Workers Power and Control in a Hong Kong Megastore WOng Heung wah The Legend ofthe Golden Boat Regulation, Trade and Traders in the Borderlands of Laos, Thailand, China and Burma Andrew walker Cultural Crisis and Social Memory Politics of the Past in the Thai World Edited by Shigeharu Tanabe and Charles R Keyes The Globalization of Chinese Food Edited by David Y. H. Wu and Sidney C. H. Cheung The Globalization of Chinese Food Edited by David Y. H. Wu and Sidney C. H. Cheung UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI'I PRESS HONOLULU Editorial Matter © 2002 David Y. -

Preliminary Concepts for the New Territories North Development

Preliminary Concepts for the New Territories North Development 02 OverviewOOvveveerrvieeww 04 ExistingEExExixisxixisssttitinng CConditionsonondddiittioonnsns 07 OpportunitiesOOppppppoortunnittiiieeses & CoCConstraintsoonnssstttrraaiainntnntss 08 OverallOOvveveerall PPlanninglananniiinnngg ApAApproachespppprrooaoacaachchchehhesess 16 OverallOOvveeraall PPlPlanninglalaannnnnniiinnngg & DesignDDeesessign FrameworkFrarammeeewwoworrkk 20 BroadBBrBroroooaadd LandLaLandnd UUsUseses CoCConceptsoonnccecepeptptss 28 NextNNeexexxt StepStStept p Overview Background 1.4 The Study adopts a comprehensive and integrated approach to formulate the optimal scale of development 1.1 According to the latest population projection, Hong in the NTN. It has explored the potential of building new Kong’s population would continue to grow, from 7.24 communities and vibrant employment and business million in 2014 to 8.22 million by 2043. There is a nodes in the area to contribute to the long-term social continuous demand for land for economic development and economic development of Hong Kong. to sustain our competitiveness. There are also increasing community aspirations for a better living environment. 1.5 The Study is a preliminary feasibility study which has examined the baseline conditions of the NTN covering 1.2 To maintain a steady land supply, the Government is about 5,300 hectares (ha) of land (Plan 1) to identify looking into various initiatives, including exploring further potential development areas (PDAs) and formulate an development opportunities in the -

Intermediates1#1 Gettingajobinhongkong

LESSON NOTES Intermediate S1 #1 Getting a Job in Hong Kong CONTENTS 2 Traditional Chinese 2 Jyutping 3 English 3 Vocabulary 4 Sample Sentences 6 Vocabulary Phrase Usage 6 Grammar 7 Cultural Insight # 1 COPYRIGHT © 2013 INNOVATIVE LANGUAGE LEARNING. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. TRADITIONAL CHINESE 1. A: 2. B: 3. A: 4. B: 5. A: 6. B: 7. A: "" 8. B: JYUTPING 1. A: ze3 man6 seng1, ni1 dou6 hai6 mai6 ceng2 jan4 aa3 ? 2. B: hai6, nei5 soeng2 gin3 bin1 fan6 gung1 ? 3. A: ngo5 hai6 lei4 jing3 ping3 coi4 mou3 ging1 lei5 ge3. 4. B: hai2 ni1 hong4 zou6 zo2 gei2 noi6 ? 5. A: ngo5 aam1 aam1 bat1 jip6, zung6 bin1 zou6 bin1 hok6. 6. B: gam2 nei5 gok3 dak1 zi6 gei2 jau5 me1 jau1 sai3 ? CONT'D OVER CANTONES ECLAS S 101.COM INTERMEDIATE S1 #1 - GETTING A JOB IN HONG KONG 2 7. A: ngo5 hai2 sei3 daai6 sat6 zaap6 zo2 bun3 nin4, jau5 wui6 gai3 si1 paai4. 8. B: hou2, min6 si5 git3 gwo2 ngo5 dei6 wui5 jau5 zyun1 jan4 tung1 zi1 nei5. ENGLISH 1. A: Excuse me, is the company looking for employees? 2. B: Yes, what kind of position are you looking for? 3. A: I'm here for the financial manager position. 4. B: How long have you been working in this field? 5. A: I've just graduated. I'm looking for work while I learn more. 6. B: So, why do you think you're a good hire? 7. A: I've been an intern with one of the Top Four accounting companies for half a year, and I've got an accounting certificate. -

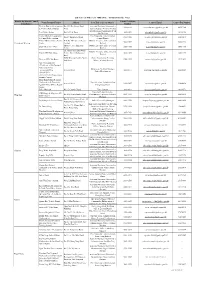

List of Access Officer (For Publication)

List of Access Officer (for Publication) - (Hong Kong Police Force) District (by District Council Contact Telephone Venue/Premise/FacilityAddress Post Title of Access Officer Contact Email Conact Fax Number Boundaries) Number Western District Headquarters No.280, Des Voeux Road Assistant Divisional Commander, 3660 6616 [email protected] 2858 9102 & Western Police Station West Administration, Western Division Sub-Divisional Commander, Peak Peak Police Station No.92, Peak Road 3660 9501 [email protected] 2849 4156 Sub-Division Central District Headquarters Chief Inspector, Administration, No.2, Chung Kong Road 3660 1106 [email protected] 2200 4511 & Central Police Station Central District Central District Police Service G/F, No.149, Queen's Road District Executive Officer, Central 3660 1105 [email protected] 3660 1298 Central and Western Centre Central District Shop 347, 3/F, Shun Tak District Executive Officer, Central Shun Tak Centre NPO 3660 1105 [email protected] 3660 1298 Centre District 2/F, Chinachem Hollywood District Executive Officer, Central Central JPC Club House Centre, No.13, Hollywood 3660 1105 [email protected] 3660 1298 District Road POD, Western Garden, No.83, Police Community Relations Western JPC Club House 2546 9192 [email protected] 2915 2493 2nd Street Officer, Western District Police Headquarters - Certificate of No Criminal Conviction Office Building & Facilities Manager, - Licensing office Arsenal Street 2860 2171 [email protected] 2200 4329 Police Headquarters - Shroff Office - Central Traffic Prosecutions Enquiry Counter Hong Kong Island Regional Headquarters & Complaint Superintendent, Administration, Arsenal Street 2860 1007 [email protected] 2200 4430 Against Police Office (Report Hong Kong Island Room) Police Museum No.27, Coombe Road Force Curator 2849 8012 [email protected] 2849 4573 Inspector/Senior Inspector, EOD Range & Magazine MT. -

The Darkest Red Corner Matthew James Brazil

The Darkest Red Corner Chinese Communist Intelligence and Its Place in the Party, 1926-1945 Matthew James Brazil A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a Doctor of Philosophy Department of Government and International Relations Business School University of Sydney 17 December 2012 Statement of Originality This is to certify that to the best of my knowledge, the content of this thesis is my own work. This thesis has not been submitted previously, either in its entirety or substantially, for a higher degree or qualifications at any other university or institute of higher learning. I certify that the intellectual content of this thesis is the product of my own work and that all the assistance received in preparing this thesis and sources has been acknowledged. Matthew James Brazil i ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Before and during this project I met a number of people who, directly or otherwise, encouraged my belief that Chinese Communist intelligence was not too difficult a subject for academic study. Michael Dutton and Scot Tanner provided invaluable direction at the very beginning. James Mulvenon requires special thanks for regular encouragement over the years and generosity with his time, guidance, and library. Richard Corsa, Monte Bullard, Tom Andrukonis, Robert W. Rice, Bill Weinstein, Roderick MacFarquhar, the late Frank Holober, Dave Small, Moray Taylor Smith, David Shambaugh, Steven Wadley, Roger Faligot, Jean Hung and the staff at the Universities Service Centre in Hong Kong, and the kind personnel at the KMT Archives in Taipei are the others who can be named. Three former US diplomats cannot, though their generosity helped my understanding of links between modern PRC intelligence operations and those before 1949.