Caste &Class IN

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CENTRAL LIST of OTHER BACKWARD CLASSES Sl

CENTRAL LIST OF OTHER BACKWARD CLASSES Sl.No. Name of the Castes/Sub-castes/Synonyms/ Entry No. in the Communities Central List BIHAR 1 Abdal 1 2 Agariya 2 3 Aghori 3 4 Amaat 4 5 Bagdi 77 6 Bakho (Muslim) 130 7 Banpar 113 8 Barai 82 9 Barhai (Viswakarma) 81 10 Bari 78 11 Beldar 79 12 Bhar 85 13 Bhaskar 86 14 Bhat, Bhatt 88 15 Bhathiara (Muslim) 84 16 Bind 80 17 Bhuihar, Bhuiyar 87 18 Chain, Chayeen 39 19 Chapota 40 20 Chandrabanshi (Kahar) 41 21 Chanou 43 22 Chik (Muslim) 38 23 Christian converts from Other Backward Classes 121 24 Christian converts from Scheduled Castes 120 25 Churihar (Muslim) 42 26 Dafali (Muslim) 46 27 Dangi 123 28 Devhar 55 29 Dhamin 59 30 Dhanuk 56 31 Dhanwar 122 32 Dhankar 60 33 Dhekaru 47 34 Dhimar 61 35 Dhobi (Muslim) 57 36 Dhunia (Muslim) 58 37 Gaddi 30 38 Gandarbh or Gandharb 31 39 Gangai (Ganesh) 32 40 Gangota, Gangoth 33 41 Ghatwar 37 42 Godi (Chhava) 29 43 Gorh, Gonrh (only in the district of Saran & Rohtas) 34 44 Goud 36 45 Gulgaliya 35 46 Idrisi or Darzi (Muslim) 119 47 Jogi (Jugi) 44 48 Kadar 7 49 Kaivartta/Kaibartta 8 50 Kagzi 16 51 Kalandar 9 52 Kalwar 124(a) Kalal, Eraqui 124(b) 53 Kamar (Lohar, Karmakar, Visvakarma) 18 54 Kanu 17 55 Kapadia 20 56 Kasab (Kasai) (Muslim) 5 57 Kaura 10 58 Kawar 11 59 Kewat 6 Keot 60 Khadwar (only in the district of Sivan and Rohtas) 26 61 Khangar 23 62 Khatik 22 63 Khatwa 24 64 Khatwe 25 65 Khelta 28 66 Khetauri, Khatauri 27 67 Kochh 12 68 Korku 13 69 Kosta, Koshta 21 70 Kumarbhag Pahadia 14 71 Kulahia 125 72 Kurmi 15 Kurmi (Mahto) (in Chhotanagpur Division only) 73 -

2021 Daily Prayer Guide for All People Groups & Unreached People

2021 Daily Prayer Guide for all People Groups & Unreached People Groups = LR-UPGs = of South Asia Joshua Project data, www.joshuaproject.net (India DPG is separate) AGWM Western edition I give credit & thanks to Create International for permission to use their PG photos. 2021 Daily Prayer Guide for all People Groups & LR-UPGs = Least-Reached-Unreached People Groups of South Asia = this DPG SOUTH ASIA SUMMARY: 873 total People Groups; 733 UPGs The 6 countries of South Asia (India; Bangladesh; Nepal; Sri Lanka; Bhutan; Maldives) has 3,178 UPGs = 42.89% of the world's total UPGs! We must pray and reach them! India: 2,717 total PG; 2,445 UPGs; (India is reported in separate Daily Prayer Guide) Bangladesh: 331 total PG; 299 UPGs; Nepal: 285 total PG; 275 UPG Sri Lanka: 174 total PG; 79 UPGs; Bhutan: 76 total PG; 73 UPGs; Maldives: 7 total PG; 7 UPGs. Downloaded from www.joshuaproject.net in September 2020 LR-UPG definition: 2% or less Evangelical & 5% or less Christian Frontier (FR) definition: 0% to 0.1% Christian Why pray--God loves lost: world UPGs = 7,407; Frontier = 5,042. Color code: green = begin new area; blue = begin new country "Prayer is not the only thing we can can do, but it is the most important thing we can do!" Luke 10:2, Jesus told them, "The harvest is plentiful, but the workers are few. Ask the Lord of the harvest, therefore, to send out workers into his harvest field." Why Should We Pray For Unreached People Groups? * Missions & salvation of all people is God's plan, God's will, God's heart, God's dream, Gen. -

Sl. NAME of CASTES Particulars of Connected Orders 1 Kapali 2 Baishya Kapali 3 Kurmi 4 Sutradhar 5 Karmakar 6 Kumbhakar 7 Swarnakar Resolution No

Central List of OBC: Sl. NAME OF CASTES Particulars of Connected Orders 1 Kapali 2 Baishya Kapali 3 Kurmi 4 Sutradhar 5 Karmakar 6 Kumbhakar 7 Swarnakar Resolution No. 12011/9/94-BCC dt. 19-10-1994 8 Teli 9 Napit 10 Yogi, Nath 11 Moira (Halwai) , Modak (Halwai) 12 Barujibi 13 Satchasi Goala, Gope Amended/Inserted vide Resolution No.12011/68/98-BCC dt. 14 (Pallav Gope, Ballav Gope, Yadav 27th Oct. 1999 of Ministry Of Social Justice and Empowerment Gope, Gope, Ahir and Yadav.) 15 Malakar 16 Jolah (Ansari-Momin) 17 Kansari Resolution No. 12011/96/94/BCC dt. 09.03.1996. 18 Tanti, Tantubaya 19 Dhanuk 20 Shankakar 21 Keori / Koiri 22 Raju 23 Nagar Resolution No. 12011/44/96/BCC dt. 06.12.1996. 24 Karani 25 Sarak 26 Kosta / Kostha Amended/Inserted vide Resolution No.12011/68/98-BCC dt. 27 Chitrakar 27th Oct. 1999 of Ministry Of Social Justice and Empowerment Resolution No.12011/88/98-BCC dt. 6th Dec 1999 of Ministry of 28 Jogi Social Justice and Empowerment Amended/Inserted vide Resolution No.12011/68/98-BCC dt. 29 Fakir, Sain 27th Oct. 1999 of Ministry Of Social Justice and Empowerment Resolution No.12011/88/98-BCC dt. 6th Dec 1999 of Ministry of 30 Nembang Social Justice and Empowerment. 31 Sampung 32 Turha Resolution No.12011/88/98-BCC dt. 6th Dec. 1999 of Ministry of 33 Bungcheng Social Justice and Empowerment 34 Bhujel 35 Kahar Resolution No.12011/68/98-BCC dt. 27th Oct. 1999 of Ministry 36 Betkar Of Social Justice and Empowerment Sukli (Excluding Solanki Rajputs who 37 Resolution No.12011/88/98-BCC dt. -

2020 South Asia

2020 Daily Prayer Guide for all People Groups & Unreached People Groups = LR-UPGs - of South Asia Source: Joshua Project data, www.joshuaproject.net 2020 Western edition (India DPG is separate) To order prayer resources or for inquiries, contact email: [email protected] INTRODUCTION & EXPLANATION Introduction Page i All Joshua Project people groups & “Least Reached” (LR) / “Unreached People Groups” (UPG) downloaded in July, 2019 are included. Joshua Project considers LR & UPG as those people groups who are less than 2 % Evangelical and less than 5 % total Christian. This prayer guide is good for multiple years (2020, 2021, etc.) as there is little change (approx. 1.4% growth) each year. ** AFTER 2020 MULTIPLY POPULATION FIGURES BY 1.4 % ANNUAL GROWTH EACH YEAR. The JP-LR column lists those people groups which Joshua Project lists as “Least Reached” (LR), indicated by LR. Frontier people groups = FR, are 0.1% Christian or less, the most needy UPGs. White rows shows people groups JP lists as “Least Reached” LR or FR, while shaded rows are not considered LR-UPG people groups by Joshua Project. Luke 10:2, Jesus told them, "The harvest is plentiful, but the workers are few. Ask the Lord of the harvest, therefore, to send out workers into his harvest field." Therefore, let's pray daily for South Asia's people groups & LR-UPGs! Introduction Page ii UNREACHED PEOPLE GROUPS IN SOUTH ASIA Mission leaders with Lausanne Committee for World Evangelization (LCWE) meeting in Chicago in 1982 developed this official definition of a PEOPLE GROUP: “a significantly large ethnic / sociological grouping of individuals who perceive themselves to have a common affinity to one another [on the basis of ethnicity, language, tribe, caste, class, religion, occupation, location, or a combination]. -

National Commission for Religious and Linguistic Minorities Annexures to the Report of The

National Commission for Religious and Linguistic Minorities Annexure to the Report of the National Commission for Annexure to the Report of Religious and Linguistic Minorities Volume - II Ministry of Minority Affairs Annexures to the Report of the National Commission for Religious and Linguistic Minorities Volume II Ministry of Minority Affairs ii Designed and Layout by New Concept Information Systems Pvt. Ltd., Tel.: 26972743 Printing by Alaknanda Advertising Pvt. Ltd., Tel.: 9810134115 Annexures to the Report of the National Commission for Religious and Linguistic Minorities iii Contents Annexure 1 Questionnaires Sent 1 Annexure 1.1 Questionnaries sent to States/UTs 1 Annexure 1.2 Supplementary Questionnaire sent to States/UTs 17 Annexure 1.3 Questionnaire sent to Districts 19 Annexure 1.4 Questionnaire sent to Selected Colleges 33 Annexure 1.5 Format Regarding Collection of Information/Data on Developmental/ Welfare Schemes/Programmes for Religious and Linguistic Minorities from Ministries/Departments 36 Annexure 2 Proceedings of the Meeting of the Secretaries, Minorities Welfare/ Minorities Development Departments of the State Governments and Union Territory Administrations held on 13th July, 2005 38 Annexure 3 List of Community Leaders/Religious Leaders With Whom the Commission held Discussions 46 Annexure 4 Findings & Recommendations of Studies Sponsored by the Commission 47 Annexure 4.1 A Study on Socio-Economic Status of Minorities - Factors Responsible for their Backwardness 47 Annexure 4.2 Educational Status of Minorities and -

CABA-MDTP REG LIST JULY-2017.Xlsx

1 Candiates Registered in CABA-MDTP JULY-2017 Session centre_code registration_no Candidate Particulars 110006 1707110006001 RUBEENA BEGUM D/o MOHD SHABBIR AHMED 110006 1707110006002 SYEDA ASRA AMTUL KHATIJA D/o SYED HABEEBULLAH KHADRI 110006 1707110006003 AMREEN FATIMA D/o MOHAMMED CHAND PASHA 110006 1707110006004 NAZIA BEGUM D/o MOHD ISMAIL 110006 1707110006005 NIKHAT SULTANA D/o MOHD KHAJA 110006 1707110006006 ASMA BEGUM D/o MOHD IQBAL 110006 1707110006007 SHAHEDA BEGUM D/o MOHD IQBAL 110006 1707110006008 AFREEN BEGUM D/o MOHD GHOOSE 110006 1707110006009 ADIBA FATIMA D/o MOHD ABDUL SAMEE 110006 1707110006010 YAMEEN FANTESAR D/o SYED AMEER ULLAH HUSSAINI 110006 1707110006011 AZIZA BEGUM D/o MIRZA LIYAQATHULLAH BAIG 110006 1707110006012 MOHAMMED SULTAN MOHIUDDIN S/o MOHAMMED KHALEEL AHMED 110006 1707110006013 MOHD SAMAD S/o YAKUB ALI 110006 1707110006014 MOHD ABDUL MUQTADIR S/o MOHD ABDUL SAMEE 110006 1707110006015 MUMTAZ AHMED SIDDIQUE S/o MINHAJUDDIN 110006 1707110006016 MOHAMMAD ABDUL BATIN S/o MOHAMMAD ABDUL RASHEED 110006 1707110006017 MD RAHEEM S/o MD RUSTUM 110006 1707110006018 MOHAMMED HAMEEDUDDIN S/o MOHAMMED RIYAZUDDIN 110006 1707110006019 SYED SAMI S/o SYED NISAR 110006 1707110006020 ABDUL RAHMAN S/o SARFARAZ AHMED 110006 1707110006021 SYED OSMAN QADRI S/o SYED KHADAR QADRI 110006 1707110006022 MOHD IRBAZ ZAKARIA S/o MOHD YAQOOB KALEEM 110006 1707110006023 MOHD SHOEB S/o MOHD FAROOQ 110006 1707110006024 MUHAMMAD KAMRAN AZEEZ S/o MUHAMMAD AZEEZ AKHTAR 110006 1707110006025 ABDUL MAJEED S/o ABDUL SATTAR 110006 1707110006026 SHAIK -

Abu Road Agar Malwa Agra

ABU ROAD SHOE MARKET SANJAY PLACE (BE HIND DOC TOR SOAP BUILD ING)-282002 ALOK RINKAL & AS SO CI ATES 018770C ALOK MITTAL 411774 1 ABU ROAD RINKAL MITTAL 411955 1 A J S R & AS SO CI ATES 020881C ATUL GOYAL 534034 1 A J P & AS SO CI ATES 137050W MOHIT AGARWAL 408406 1 7 INDRA COL ONY SHOP NO 4 UP PER GROUND FLOOR MAYANK JINDAL 421932 1 BHOGIPURA KAVITA COM PLEX * RAJESH KUMAR SINGH 424068 1 SHAHGANJ-282010 788/1 SECTOR-7 OPP BUS STAND Also at NEW DELHI AVAS VIKAS COLONY SIROHI-307026 SIKANDRA-282007 Head Of fice at MUMBAI Also at SECTOR 4 - A/156 ALOK VRITIK & CO 010344C EWS AVAS VIKAS COLONY 15 NEHRU NAGAR-282002 BODLA-282007 A P SANZGIRI & CO 116293W Head Of fice at MEERUT Also at A-30 RIICO COL ONY-307026 VIL LAGE LOKHARERA Head Of fice at MUMBAI POST RUNKATA-282007 AMBIKA PRASAD SHARMA & CO 007127C AMBIKA PRASAD SHARMA 072542 1 SURBHI JAIN 423003 1 022256C AGARWAL A R & AS SO CI ATES A K HAJELA & CO 000901C 6 NEHRU NAGAR-282002 * RAKESH AGRAWAL 176586 1 HAJELA ADITYA KUMAR 070377 1 * RONAK AGARWAL 433088 1 HAJELA AMAR KANT 070380 1 F 4 FIRST FLOOR ROOM NO 9 2ND FLOOR DEV COMPLEX RAJENDRA MARKET ANAND RAJENDRA & CO 324092E AMBAJI ROAD-307026 HOS PI TAL ROAD-282003 C/O ANIL KUMAR JAIN Also at AHMEDABAD 39/77 NEW IDGAH COL ONY SIROHI NEAR DEVIKAMANDIR UTTAR PRADESH-282001 Head Of fice at KOLKATA ADIWISE M K & AS SO CI ATES 007180N 3/29 PRATAP PURA-282001 CHOUDHARY AMIT & AS SO CI ATES 020192C Head Of fice at JHAJJAR AMIT CHOUDHARY 427238 1 * DHARMENDRA KUMAR SHARMA 429301 1 ANCHAL JAIN & AS SO CI ATES 017959C KANISHKA SHARMA 433597 1 -

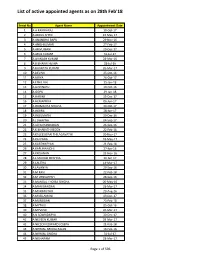

List of Active Appointed Agents As on 28Th Feb'18

List of active appointed agents as on 28th Feb'18 Serial No Agent Name Appointment Date 1 A A KANIKARAJ 30-Oct-17 2 A ABDUL SHEIK 24-May-17 3 A ANANDHA BAPU 29-Nov-16 4 A ANISHKUMAR 27-Feb-17 5 A ARIVUMANI 29-Dec-17 6 A ARUL KUMAR 31-Jul-17 7 A AVINASH KUMAR 28-Mar-16 8 A B BHARATHESHA 28-Jul-16 9 A BHARATH KUMAR 20-Mar-17 10 A DEVAKI 25-Oct-16 11 A DIVYA 26-Oct-17 12 A EZHIL RAJ 25-Jan-18 13 A GOPINATH 10-Oct-16 14 A GOPU 29-Jan-18 15 A HARINI 19-Dec-17 16 A HEMAPRIYA 06-Jun-17 17 A IBOMACHA SINGHA 30-Oct-17 18 A INDIRA 28-Jun-17 19 A INDUMATHI 30-Dec-16 20 A J SWAPNA 04-Sep-17 21 A JAYACHANDARAN 26-Sep-16 22 A K BHARATH REDDY 22-Feb-16 23 A KALEESWARI THILAGAVATHI 20-Nov-17 24 A KALPANA 18-May-17 25 A KARTHIKEYAN 21-Feb-18 26 A KARUNANIDHI 27-Jun-16 27 A KRISHNAN 29-Nov-16 28 A L MURALI KRISHNA 29-Jun-17 29 A LALITHA 14-Mar-17 30 A LAVANYA 29-Sep-16 31 A M RAVI 22-Feb-18 32 A M VENKATESH 28-Sep-16 33 A MANGAL THOIBA SINGHA 06-May-16 34 A MANIGANDAN 28-Mar-17 35 A MARIMUTHU 29-Aug-16 36 A MASILAMANI 19-Dec-17 37 A MURUGAN 23-Feb-18 38 A MYTHILI 05-Oct-16 39 A MYVIZHI 20-Mar-17 40 A N SOWNDARYA 30-Dec-17 41 A NEVEEN KUMAR 29-Mar-17 42 A NICSON EDWARD JOSEPH 21-Feb-18 43 A NIRMAL AROKIA RAJAN 16-Feb-16 44 A NIRMAL SINGHA 31-Jul-17 45 A NISHARAM 28-Mar-17 Page 1 of 596 List of active appointed agents as on 28th Feb'18 Serial No Agent Name Appointment Date 46 A P MOHANA CHANDRAN 28-Mar-16 47 A PRADEEP KUMAR 28-Nov-17 48 A R SEETHALAKSHMI 20-Jan-16 49 A R VENKAT RAGHAVAN 28-Mar-13 50 A RAGUVARAN 24-Mar-17 51 A RAJAGOPAL 20-Feb-18 52 A RAMANATHAN -

West Bengal Commission for Backward Classes Rayeen/Kunjra Class Report

WEST BENGAL COMMISSION FOR BACKWARD CLASSES RAYEEN/KUNJRA CLASS R E P O R T The West Bengal Commission for Backward Classes received applications dated 05.03.2001 from the President, JAM-AIT-UR-RAYEEN, West Bengal, 10E, Gopal Chatterjee Road, Cossipore, Kolkata – 700 002, praying for inclusion of the ‘Rayeen’ class, also known as ‘Kunjra’, in the list Backward Classes in West Bengal, The applicant also submitted relevant information in the proforma prescribed by the Commission. 2. The applicant has stated that the population of the Rayeen/Kunjra class in West Bengal is about 26 lakh with equal distribution of males and females. Their population is spread over the district of Kolkata, North & South 24-Parganas, Howrah, Purulia, Malda, Murshidabad, Bardhaman, Birbhum and Jalpaiguri. It appears from the information furnished by the applicant that the class constitutes an endogamic social group and it is not possible for any other group to infiltrate into this social group unnoticed. The members of the class are mainly fruit and vegetable sellers. No one treats them as respectable persons; only 10% of the people in the locality treat them as ordinary persons without showing any voluntary disrespect, but 90% of the people in the locality treat them like persons belonging to the Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes. 3. It has been stated that the people belonging to Rayeen/Kunjra class earn their livelihood by selling fruits and vegetables, by hawking and door-to-door selling and working as labourers in agriculture and industries. 4. It has been stated that 10% of the population of the Class live in thatched houses, 75% live in mud-wall and kutcha houses, 10% live in semi-pucca houses and only 5% live in pucca houses as tenants. -

Birla Vidya Niketan Nursery Admission 2018-19

Circular: Nur-Admn/05/2018 Date:-14-02-2018 Birla Vidya Niketan New Delhi -17 Nursery Admission 2018-19 Final List of Registered Applicants for Draw of lots 1. Out of the total applicants from the neighbourhood range of 0-8 kms, computerized lottery draws will be held for selecting successful candidates for sibling seats(34), Alumni seats(12), girl child category seats (11) and Neighbourhood category seats (57). 2. Applicants residing beyond 8 kms shall be admitted only in case vacancies remain unfilled after considering all students within 8 kms after following the procedure as mentioned above. Neighbourhood and Sibling Criteria- No. of Seats 34 REG. NO NAME GENDER FATHER NAME MOTHER NAME 4 ANISHA MISHRA female ANIMESH KUMAR MISHRA SHAKUNTALA JHA 25 ANSHIKA GOEL female VISHAL GOEL ANJALI GOEL 43 IRA SHARMA female RAJEEV SHARMA SUSHMA SHARMA 71 SHIVEN KUKREJA male AJAY KUKREJA YOGITA KUKREJA 73 AISHANI MITTAL female DIVYA KUMAR MITTAL DR NIDHI MITTAL 83 PRIYANSHI MEHTA female SUNDEEP MEHTA NAINA MEHTA 152 TANISHH GOLCHHA male RISHI GOLCHHA RUCHI GOLCHHA 158 AARAV SEMWAL male SUNIL KUMAR SEMWAL LATE SMT JYOTI PRABHA SEMWAL 163 DRISHTI MEERWAL female RAJENDRA MANJU 164 AMYRA KUMAR female RAHUL KUMAR DIVYA KUMAR 204 PRABHANSH SINGH male PARMINDER SINGH TEJINDER KAUR 214 ANANT SHARMA male GYANENDRA KUMAR SHARMA PRIYANKA SHARMA 245 EKANSHI MATHURIA female RAKESH KUMAR MANJU SINGH 261 KIARA female AMIT KUMAR KANIKA 281 SREYOSHI DASGUPTA female RATNESH DASGUPTA SUJATA DASGUPTA 313 AMYRA SINGH female ABHISHEK KUMAR NIDHI SINGH 334 RIDHI GARG female -

Of INDIA Source: Joshua Project Data, 2019 Western Edition Introduction Page I INTRODUCTION & EXPLANATION

Daily Prayer Guide for all People Groups & Unreached People Groups = LR-UPGs - of INDIA Source: Joshua Project data, www.joshuaproject.net 2019 Western edition Introduction Page i INTRODUCTION & EXPLANATION All Joshua Project people groups & “Least Reached” (LR) / “Unreached People Groups” (UPG) downloaded in August 2018 are included. Joshua Project considers LR & UPG as those people groups who are less than 2 % Evangelical and less than 5 % total Christian. The statistical data for population, percent Christian (all who consider themselves Christian), is Joshua Project computer generated as of August 24, 2018. This prayer guide is good for multiple years (2018, 2019, etc.) as there is little change (approx. 1.4% growth) each year. ** AFTER 2018 MULTIPLY POPULATION FIGURES BY 1.4 % ANNUAL GROWTH EACH YEAR. The JP-LR column lists those people groups which Joshua Project lists as “Least Reached” (LR), indicated by Y = Yes. White rows shows people groups JP lists as “Least Reached” (LR) or UPG, while shaded rows are not considered LR people groups by Joshua Project. For India ISO codes are used for some Indian states as follows: AN = Andeman & Nicobar. JH = Jharkhand OD = Odisha AP = Andhra Pradesh+Telangana JK = Jammu & Kashmir PB = Punjab AR = Arunachal Pradesh KA = Karnataka RJ = Rajasthan AS = Assam KL = Kerala SK = Sikkim BR = Bihar ML = Meghalaya TN = Tamil Nadu CT = Chhattisgarh MH = Maharashtra TR = Tripura DL = Delhi MN = Manipur UT = Uttarakhand GJ = Gujarat MP = Madhya Pradesh UP = Uttar Pradesh HP = Himachal Pradesh MZ = Mizoram WB = West Bengal HR = Haryana NL = Nagaland Introduction Page ii UNREACHED PEOPLE GROUPS IN INDIA AND SOUTH ASIA Mission leaders with Lausanne Committee for World Evangelization (LCWE) meeting in Chicago in 1982 developed this official definition of a PEOPLE GROUP: “a significantly large ethnic / sociological grouping of individuals who perceive themselves to have a common affinity to one another [on the basis of ethnicity, language, tribe, caste, class, religion, occupation, location, or a combination]. -

Rangpur, Bangladesh, UPG 2018

Country State People Group Language Religion Bangladesh Rangpur Abdul Bengali Islam Bangladesh Rangpur Aguri Bengali Hinduism Bangladesh Rangpur Ansari Bengali Islam Bangladesh Rangpur Arora (Sikh traditions) Punjabi, Western Other / Small Bangladesh Rangpur Badaik Bengali Hinduism Bangladesh Rangpur Bagdi (Hindu traditions) Bengali Hinduism Bangladesh Rangpur Baha'i Bengali Other / Small Bangladesh Rangpur Bahelia (Hindu traditions) Bengali Hinduism Bangladesh Rangpur Baidya (Hindu traditions) Bengali Hinduism Bangladesh Rangpur Bairagi (Hindu traditions) Bengali Hinduism Bangladesh Rangpur Baiti Bengali Hinduism Bangladesh Rangpur Bania Bengali Hinduism Bangladesh Rangpur Bania Agarwal Bengali Hinduism Bangladesh Rangpur Bania Khatri Bengali Hinduism Bangladesh Rangpur Bania Rauniar Bengali Hinduism Bangladesh Rangpur Barua Chittagonian Buddhism Bangladesh Rangpur Bauri Bengali Hinduism Bangladesh Rangpur Bedia (Hindu traditions) Bengali Hinduism Bangladesh Rangpur Behara Bengali Islam Bangladesh Rangpur Beldar (Hindu traditions) Bengali Hinduism Bangladesh Rangpur Besya (Muslim traditions) Bengali Islam Bangladesh Rangpur Bhangi (Hindu traditions) Bengali Hinduism Bangladesh Rangpur Bhar Bengali Hinduism Bangladesh Rangpur Bhat (Hindu traditions) Bengali Hinduism Bangladesh Rangpur Bhoi (Hindu traditions) Bengali Hinduism Bangladesh Rangpur Bhotia Tibetan Sikkimese Buddhism Bangladesh Rangpur Bhuinhar Bengali Hinduism Bangladesh Rangpur Bhuinmali Bengali Hinduism Bangladesh Rangpur Bhuiya Bengali Hinduism Bangladesh Rangpur Bhunjia