Transport in Mikrorayons: Accessibility and Proximity to Centrally Planned

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Homeowners Associations in the Former Soviet Union: Stalled on The

Homeowners Associations in the Former Soviet Union: Stalled on the Road to Reform prepared by Barbara J. Lipman AN IHC PUBLICATION FEBRUARY 2012 International Housing Coalition Supporting Housing for All in a Rapidly Urbanizing World photo: © Habitat for Humanity International An IHC Publication PREFACE This paper, reprinted with permission from the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development/The World Bank, reviews the progress that is being made in countries of the former Soviet Union to establish Homeownership Associations (HOAs) to manage and operate privatized, multifamily buildings. The International Housing Coalition (IHC) is publishing this paper because it shines a spotlight on the challenges encountered in moving from a system of heavily subsidized government-owned housing to one in which the housing is owned and managed by the occupants. The situation the paper describes is one of largely stalled progress. The report provides recommendations about how to eliminate obstacles that discourage the formation of HOAs and that hinder reforms in the broader private mainte- nance and utility sectors. More competent and effective HOAs can help strengthen the private property market and improve the marketability and the value of privately owned multifamily housing units. The IHC is a non-profit advocacy organization located in Washington D.C. that supports housing for all and seeks to raise the priority of housing on the international development agenda. The conditions of slums and the poor housing of slum dwellers are of particular concern. The IHC supports the basic principles of private property rights, secure tenure, effective title systems and efficient and equitable housing finance systems—all essential elements to economic growth, civic stability, and democratic values. -

A New Southern Downtown? Gentrification in Ferencváros, Budapest and Södermalm, Stockholm

Fälkursbudget vt 2008 A New Southern Downtown? Gentrification in Ferencváros, Budapest and Södermalm, Stockholm Fabian Tátrai Juni 2015 Handledare: Anna Storm Kulturgeografiska institutionen Stockholms universitet 106 91 Stockholm www.humangeo.su.se Examensarbete i samhällsplanering 30 hp, masteruppsats Tátrai, Fabian (2015) A New Southern Downtown? - Gentrification in Ferencváros, Budapest and Södermalm, Stockholm Urban and Regional Planning, advanced level, master thesis for master exam in Urban and Regional Planning, 30 ECTS credits Supervisor: Anna Storm Language: English The aim of the thesis is to analyze how residents in the Ferencváros district of Budapest, Hungary and the Södermalm district of Stockholm, Sweden experience the urban regenerations in the area, which have caused gentrification. The theory is that gentrification is an effect of regeneration, and may be perceived as positive or negative to a different degree. The areas of research are defined as having similar relative geographic positions and have both been affected by gentrification. The research questions are about emotions of change, perceived authenticity and engagement for the areas. The main method is in-depth interviews with residents and businessmen in the areas. Also concrete renewal policies and economic indicators are presented shortly. The results show that the respondents in Ferencváros are generally more positive towards the changes. The emotions of authenticity and engagement are slightly stronger in Södermalm. The conclusion of the thesis is that gentrification is at a later phase in Södermalm, than in Ferencváros. Ferencváros has also been more unevenly affected by gentrification. Keywords: Budapest, Ferencváros, Stockholm, Södermalm, Urban, Renewal, Regeneration, Gentrification 1 Preface I would like to say a big Thank You to Anna Storm, who has been my Supervisor for this thesis, and who has helped me a lot with finding the relevant inputs and material for the study, and who has been a great support along the process of work. -

Ess4 - 2008 Documentation Report

ESS4 - 2008 DOCUMENTATION REPORT THE ESS DATA ARCHIVE Edition 5.5 Version Notes, ESS4 - 2008 Documentation Report ESS4 edition 5.5 (published 01.12.18): Applies to datafile ESS4 edition 4.5. Changes from edition 5.4: Czechia: Country name changed from Czech Republic to Czechia in accordance with change in ISO 3166 standard. 25 Version notes. Information updated for ESS4 ed. 4.5 data. 26 Completeness of collection stored. Information updated for ESS4 ed. 4.5 data. Israel: 46 Deviations amended. Deviation in F1-F4 (HHMMB, GNDR-GNDRN, YRBRN-YRBRNN, RSHIP2-RSHIPN) added. Appendix: Appendix A3 Variables and Questions and Appendix A4 Variable lists have been replaced with Appendix A3 Codebook. ESS4 edition 5.4 (published 01.12.16): Applies to datafile ESS4 edition 4.4. Changes from edition 5.3: 25 Version notes. Information updated for ESS4 ed.4.4 data. 26 Completeness of collection stored. Information updated for ESS4 ed.4.4 data. Slovenia: 46 Deviations. Amended. Deviation in B15 (WRKORG) added. Appendix: A2 Classifications and Coding standards amended for EISCED. A3 Variables and Questions amended for EISCED, WRKORG. Documents: Education Upgrade ESS1-4 amended for EISCED. ESS4 edition 5.3 (published 26.11.14): Applies to datafile ESS4 edition 4.3 Changes from edition 5.2: All links to the ESS Website have been updated. 21 Weighting: Information regarding post-stratification weights updated. 25 Version notes: Information updated for ESS4 ed.4.3 data. 26 Completeness of collection stored. Information updated for ESS4 ed.4.3 data. Lithuania: ESS4 - 2008 Documentation Report Edition 5.5 2 46 Deviations. -

Rediscovering Socialist Neighbourhoods in a New Capitalist Society Case in Vilnius Lithuania

CITY, CATCH THE TIME! Rediscovering socialist neighbourhoods in a new capitalist society Case in Vilnius Lithuania Justina Muliuolyte 1535544 TU Delft, MSc Urbanism Complex Cities Studio, P5 Presentation, June 2010 Contents Problems of housing estates Problems of post-socialist city Vilnius Vision for the city Strategy and design Evaluation Problems of two scales Neighbourhood City Declining large scale housing estates Sprawling post socialist Vilnius New city structure is a way to revitalize neighbourhoods Advantages of microdistricst will contribute to new city structure Problems of large scale housing estates Decline of post war housing - Post war housing - once a dream of every family, now - decline - In 1970s modern city criticized for the lack of human scale, monotony and mono functionality - High crime rates and social problems. - In 1970s most western cities have started renewal programs 1973 Demolition of blocks Pruitt-Igoe in St. Louis, Missouri Bijlmermeer, Amsterdam Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pruitt-Igoe; httpera.on.cablogstowerrenewalpaged=3 Large scale housing estates in post-socialist cities - In the USSR massive construction continued up until 1990s Village - Neighborhoods in the east-central Europe are much less Prague deteriorated, then their western counterparts Moscow Vilnius Vilnius Budapest Kaunas Bucharest Berlin Former East Block countries Cities with biggest amount of large housing estates RoleAverage of LT housing income 32% estates of average in EU post-socialist income cities Household income Apartment -

Soviet Neighbourhood with Nature-Based Solutions

DOI: 10.2478/ahr-2020-0016 Aleksandr Shchur, Nadzeya Lobikava, Volha Lobikava Acta Horticulturae et Regiotecturae 2/2020 Acta Horticulturae et Regiotecturae 2 Nitra, Slovaca Universitas Agriculturae Nitriae, 2020, pp. 76–80 REVITALIZATION OF (POST-) SOVIET NEIGHBOURHOOD WITH NATURE-BASED SOLUTIONS Aleksandr SHCHUR, Nadzeya LOBIKAVA*, Volha LOBIKAVA Belarusian-Russian University, Mogilev, Republic of Belarus The neighbourhoods in the former Soviet Union were after the World War II often planned according to the self-consistent microdistrict concept similar to Clarence Perry’s neighbourhood unit. Each residential district was based on the walkable community centre in the middle whereas the area itself was surrounded by arterial streets as the main transport routes with basic services. However, the recent situation of many of those neighbourhoods is rather dim – the bad condition of housing, faded public spaces and unorganised greenery systems are between the most crucial issues. The results of the research made on the case study of the Jubilejny district in the city of Mogilev, Belarus, show that population ageing is the main threat for these areas. Residents are dissatisfied with uncertain housing situation besides inappropriate parking options and lack of opportunities to spend a leisure time outside. Therefore, our proposal to the future development of the Jubilejny district includes short term improvements such as leisure activities within the public spaces or regeneration of green spaces as well as long-term designs regarding a community garden and other nature-based solutions. Keywords: nature-based solutions, khrushchyevka, microdistrict, urban greenery After the World War II, the scale of industry has grown extreme events (e.g. -

László Jeney – Dávid Karácsonyi (Eds.)

László Jeney – Dávid Karácsonyi (eds.) Department of Economic Geography and Futures Studies, Corvinus Univ. of Budapest Geographical Institute, RCAES Hungarian Academy of Sciences Faculty of Geography, Belarusian State University Institute for Nature Management, National Academy of Sciences of Belarus Minsk and Budapest, the two capital cities Selected studies of post-socialist urban geography and ecological problems of urban areas The publication was supported by Department of Economic Geography and Future Studies of Corvinus University of Budapest, by International Visegrad Fund and by the bilateral agreement on researcher’s mobility between Hungarian Academy of Sciences and National Academy of Sciences of Belarus (project title: Scientific Preparation of Book-Atlas “Belarus in Maps”). László Jeney – Dávid Karácsonyi (eds.) Minsk and Budapest, the two capital cities Selected studies of post-socialist urban geography and ecological problems of urban areas Geographical Institute, RCAES Institute for Nature Management, Hungarian Academy of Sciences National Academy of Sciences of Belarus Department of Economic Faculty of Geography, Geography and Futures Studies, Belarusian State University Corvinus University of Budapest Budapest – Minsk, 2015 Edited by: László Jeney Dávid Karácsonyi Scientific review: István Tózsa English proofreading: Mária Sándori Cover design: Dávid Karácsonyi László Jeney Typography: László Jeney Budapest–Minsk 2015 ISBN 978-963-503-591-5 Printed in Hungary by Duna-Mix Publishers: István Tózsa and Péter Ábrahám © Department of Economic Geography and Futures Studies, Corvinus University of Budapest, 2015 © Geographical Institute, Research Centre for Astronomy and Earth Sciences, Hungarian Academy of Sciences, 2015 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without written permission of the publishers. -

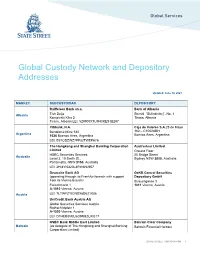

Global Custody Network and Depository Addresses

Global Custody Network and Depository Addresses Updated: June 30, 2021 MARKET SUBCUSTODIAN DEPOSITORY Raiffeisen Bank sh.a. Bank of Albania Albania Tish Daija Sheshi “Skënderbej”, No. 1 Kompleski Kika 2 Tirana, Albania Tirana, Albania LEI: 529900XTU9H3KES1B287 Citibank, N.A. Caja de Valores S.A.25 de Mayo Bartolome Mitre 530 362 – C1002ABH Argentina 1036 Buenos Aires, Argentina Buenos Aires, Argentina LEI: E57ODZWZ7FF32TWEFA76 The Hongkong and Shanghai Banking Corporation Austraclear Limited Limited Ground Floor HSBC Securities Services 20 Bridge Street Australia Level 3, 10 Smith St., Sydney NSW 2000, Australia Parramatta, NSW 2150, Australia LEI: 2HI3YI5320L3RW6NJ957 Deutsche Bank AG OeKB Central Securities (operating through its Frankfurt branch with support Depository GmbH from its Vienna branch) Strauchgasse 3 Fleischmarkt 1 1011 Vienna, Austria A-1010 Vienna, Austria Austria LEI: 7LTWFZYICNSX8D621K86 UniCredit Bank Austria AG Global Securities Services Austria Rothschildplatz 1 A-1020 Vienna, Austria LEI: D1HEB8VEU6D9M8ZUXG17 HSBC Bank Middle East Limited Bahrain Clear Company Bahrain (as delegate of The Hongkong and Shanghai Banking Bahrain Financial Harbour Corporation Limited) STATE STREET CORPORATION 1 GLOBAL CUSTODY NETWORK AND DEPOSITORY ADDRESSES MARKET SUBCUSTODIAN DEPOSITORY 1st Floor, Bldg. #2505 Harbour Gate (4th Floor) Road # 2832, Al Seef 428 Kingdom of Bahrain Manama, Kingdom of Bahrain LEI: 549300F99IL9YJDWH369 Standard Chartered Bank Bangladesh Bank Silver Tower, Level 7 Motijheel, Dhaka-1000 52 South Gulshan Commercial -

Housing Estates

CITY, CATCH THE TIME! Rediscovering socialist neighbourhoods in a new capitalist society Case in Vilnius Lithuania . Justina Muliuolyte TU Delft June 2010 Contacts: Justina Muliuolyte [email protected] +31 (0)624 944 011 www.justinamuliuolyte.eu Mentor Team: Roberto Rocco, MSc. R.C. Assistant Professor Urbanism; Chair of Spatial Planning & Strategy Bouwkunde; TU Delft [email protected] John Westrik, Ir. J.A. Associate Professor Urbanism; Chair of Urban Compositions Bouwkunde; TU Delft [email protected] Qu Lei, Teacher / Researcher Urbanism; Chair of Spatial Planning & Strategy Bouwkunde; TU Delft [email protected] External mentor: Schreurs, Drs.ir. E.P.N. [email protected] CITY, CATCH THE TIME! Rediscovering socialist neighbourhoods in a new capitalist society Case in Vilnius Lithuania . Justina Muliuolyte 1535544 TU Delft, MSc Urbanism Complex Cities Studio, Thesis report, June 2010 3 4 Contents Summary of the graduation project 8 4 - DESIgN - 92 1 - INTRoDUCTIoN - 11 Route will link microdistricts with mix use area 94 Evaluation of the public space on the route 96 Societal and academic relevance 12 Revitalization toolbox 98 Personal motivation 12 Creating urban centre 106 Problem definition 13 Creating urban street 108 Field of research and research questions 14 Program on the route 110 Methodology 16 Closed and calm courtyards 112 Aim and goal of the final project 18 New housing typology 114 Possibilities for commercial ground floor activity 116 Stakeholders 120 2 - RESEARCh - 21 Evaluation 124 Future of large scale housing -

Leonid Tyulpa. the Architect of the Soviet Period of Mass Industrial Development

Leonid Tyulpa. The architect of the soviet period of mass industrial development ALEXANDER BOURYAK IGOR LAVRENTIEV (†) NADIIA ANTONENKO Abstract The design approach employed by Kharkiv-based architect Leonid Tyulpa evolved from the early 1950s to the late 1970s. The architect’s career reflected the state of the whole Soviet architectural design in the second half of the XX century. His creative work encompassed all the milestones of housing development practice in the country. L.Tyulpa’s career started in 1951-1956 with restoration design projects in cities damaged during WW II. The years between 1956 and 1958 marked a transitional stage when the architect broke with old design traditions. In the third stage of his career, L.Tyulpa embarked on developing a new practice of designing prefabricated housing, searching for economical and feasible design solutions (1958-1963), with Pavlovo Pole housing estate being a vivid example of this period. Starting from 1963 the principles of creating the so-called “micro-districts” were implemented into the old city tissue, leading to a comprehensive reconsideration of the city and its role. The final stage of his career saw the appearance of a totally new vast housing area in Kharkiv. It was Saltovskiy housing estate for 300,000 dwellers, which became the utmost manifestation of the modernist way of thinking. Keywords Mass housing; postwar, micro-district; Soviet modernism; Tyulpa; Saltovskiy housing estate; Pavlovo Pole; Ukraine. Alexander Bouryak. Sc.D. in Theory of Architecture, Kharkiv National University of Civil Engineering and Architecture: Head of the Chair (from 1985), Professor (2009); supervision of nine Ph.D. -

John Wood Group PLC Annual Report and Accounts 2018 Contents

John Wood Group PLC Annual Report and Accounts 2018 Contents Strategic report Group financial statements Our operations, strategy and business The audited financial statements of Wood model and how we have performed for the year ended 31 December 2018 during 2018 Independent auditors' report 78 Highlights 01 Consolidated income statement 86 At a glance 02 Consolidated statement of 87 Our business model 04 comprehensive income/expense Key performance indicators 06 Consolidated balance sheet 88 Chair’s statement 07 Consolidated statement of 89 changes in equity To view and download our Chief Executive review 08 Annual Report online: Segmental review 12 Consolidated cash flow statement 90 www.woodplc.com/ar18 Financial review 20 Notes to the financial statements 91 Building a sustainable business 24 Principal risks and uncertainties 39 Company financial statements Company balance sheet 160 Governance Statement of changes in equity 161 Our approach to corporate governance Notes to the Company financial 162 and how we have applied this in 2018 statements Letter from the Chair of the Board 44 Five year summary 171 Directors’ report 46 Information for shareholders 172 Board of Directors 48 Corporate governance 50 Directors’ Remuneration Report 60 Wood is a global leader in the delivery of project, engineering and technical services in energy, industry, and the built environment. We operate in more than 60 countries, employing around 60,000 people, with revenues of around $11 billion. We provide performance-driven solutions throughout the asset life cycle, from concept to decommissioning across a broad range of industrial markets, including the upstream, midstream and downstream oil & gas; power & process; environment and infrastructure; clean energy; mining; nuclear and general industrial sectors. -

Central Asian Sources and Central Asian Research

n October 2014 about thirty scholars from Asia and Europe came together for a conference to discuss different kinds of sources for the research on ICentral Asia. From museum collections and ancient manuscripts to modern newspapers and pulp fi ction and the wind horses fl ying against the blue sky of Mongolia there was a wide range of topics. Modern data processing and Göttinger data management and the problems of handling fi ve different languages and Bibliotheksschriften scripts for a dictionary project were leading us into the modern digital age. The Band 39 dominating theme of the whole conference was the importance of collections of source material found in libraries and archives, their preservation and expansion for future generations of scholars. Some of the fi nest presentations were selected for this volume and are now published for a wider audience. Central Asian Sources and Central Asian Research edited by Johannes Reckel Central Asian Sources and Research ISBN: 978-3-86395-272-3 ISSN: 0943-951X Universitätsverlag Göttingen Universitätsverlag Göttingen Johannes Reckel (ed.) Central Asian Sources and Central Asian Research This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. Published as Volume 39 of the series “Göttinger Bibliotheksschriften” by Universitätsverlag Göttingen 2016 Johannes Reckel (ed.) Central Asian Sources and Central Asian Research Selected Proceedings from the International Symposium “Central Asian Sources and Central Asian Research”, October 23rd–26th, 2014 at Göttingen State and University Library Göttinger Bibliotheksschriften Volume 39 Universitätsverlag Göttingen 2016 Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available on the Internet at http://dnb.dnb.de. -

John Wood Group PLC Annual Report and Accounts 2019 Contents

John Wood Group PLC Annual Report and Accounts 2019 Contents Strategic report Group financial statements Our operations, strategy and business model The audited financial statements of Wood and how we have performed during 2019 for the year ended 31 December 2019 Highlights 01 Independent auditor's report 102 At a glance 02 Consolidated income statement 110 Our business model 04 Consolidated statement of 111 Innovative solutions for 06 comprehensive income/expense the energy transition Consolidated balance sheet 112 View and download our Effective engagement 08 Consolidated statement of 113 Annual Report online: with our stakeholders changes in equity woodplc.com/ar19 Key performance indicators 12 Consolidated cash flow statement 114 Chair’s statement 13 Notes to the financial statements 115 Chief Executive review 14 Segmental review 18 Company financial statements Financial review 21 Company balance sheet 186 Building a sustainable business 26 Statement of changes in equity 187 Principal risks and uncertainties 45 Notes to the Company 188 financial statements Governance Five year summary 197 Our approach to corporate governance Information for shareholders 198 and how we have applied this in 2019 Letter from the Chair of the Board 50 Directors’ report 52 Board of Directors 56 Corporate governance 58 Remuneration 72 Wood is a global leader in consulting, projects and operations solutions in energy and the built environment. We operate in more than 60 countries, employing around 55,000 people, with revenues of around $10 billion. woodplc.com Strategic report Governance Financial statements Highlights Earnings growth, margin improvement and strong cash generation. Portfolio optimisation supports strategic positioning for opportunities in energy transition and sustainable infrastructure.