1 Low Budget Audio-Visual Aesthetics in Indie Music Video and Feature Filmmaking

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SYNCHRONICITY and VISUAL MUSIC a Senior Thesis Presented to the Faculty of the Department of Music Business, Entrepreneurship An

SYNCHRONICITY AND VISUAL MUSIC A Senior Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Department of Music Business, Entrepreneurship and Technology The University of the Arts In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of BACHELOR OF SCIENCE By Zarek Rubin May 9, 2019 Rubin 1 Music and visuals have an integral relationship that cannot be broken. The relationship is evident when album artwork, album packaging, and music videos still exist. For most individuals, music videos and album artwork fulfill the listener’s imagination, concept, and perception of a finished music product. For other individuals, the visuals may distract or ruin the imagination of the listener. Listening to music on an album is like reading a novel. The audience builds their own imagination from the work, but any visuals such as the novel cover to media adaptations can ruin the preexisted vision the audience possesses. Despite the audience’s imagination, music can be visualized in different forms of visual media and it can fulfill the listener’s imagination in a different context. Listeners get introduced to new music in film, television, advertisement, film trailers, and video games. Content creators on YouTube introduce a song or playlist with visuals they edit themselves. The content creators credit the music artist in the description of the video and music fans listen to the music through the links provided. The YouTube channel, “ChilledCow”, synchronizes Lo-Fi hip hop music to a gif of a girl studying from the 2012 anime film, Wolf Children. These videos are a new form of radio on the internet. -

Longmont Potion Castle 14 Free Mp3 Download Link ""Longmont Potion Castle 14"" Free Mp3 Download Link

longmont potion castle 14 free mp3 download link ""longmont potion castle 14"" free mp3 download link. This wiki takes up the challenge of being the definitive source on all things relating to the legendary prank call artist Longmont Potion Castle – from album information to track transcriptions, from his first release LPC I (1988) to the most recent, LPC 18 (2021). How to search this wiki [ edit | edit source ] Transcriptions of LPC tracks can be navigated to by finding the collection from which the desired call is located. Individual phrases or track names can also be tossed into the search bar, though this may come with mixed results as the transcription library is currently incomplete. The wiki's navigation abilities are in the process of being updated, with the addition of Album Info Boxes, Track Info Boxes, and Category Tags to make this place much, much more clickable. How you can help [ edit | edit source ] Editors and transcribers are invited to help grow this body of transcription by either tackling a missing track or editing one in existence. Whip Masters Wanted: For better coordination on current LPC Wiki projects (and discussions on future projects), all are welcome to join our newly created Discord community, Talkin' Talkin' Whipapedia , by following this invite link. Hope to see you there! radiovalencia.fm Competitive Analysis, Marketing Mix and Traffic. The percentage of organic search referrals to this site that come from this keyword. Organic Share of Voice. The percentage of all searches for this keyword that sent traffic to this website. Search Traffic. The percentage of organic search referrals to this site that come from this keyword. -

MUSIC NOTES: Exploring Music Listening Data As a Visual Representation of Self

MUSIC NOTES: Exploring Music Listening Data as a Visual Representation of Self Chad Philip Hall A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of: Master of Design University of Washington 2016 Committee: Kristine Matthews Karen Cheng Linda Norlen Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Art ©Copyright 2016 Chad Philip Hall University of Washington Abstract MUSIC NOTES: Exploring Music Listening Data as a Visual Representation of Self Chad Philip Hall Co-Chairs of the Supervisory Committee: Kristine Matthews, Associate Professor + Chair Division of Design, Visual Communication Design School of Art + Art History + Design Karen Cheng, Professor Division of Design, Visual Communication Design School of Art + Art History + Design Shelves of vinyl records and cassette tapes spark thoughts and mem ories at a quick glance. In the shift to digital formats, we lost physical artifacts but gained data as a rich, but often hidden artifact of our music listening. This project tracked and visualized the music listening habits of eight people over 30 days to explore how this data can serve as a visual representation of self and present new opportunities for reflection. 1 exploring music listening data as MUSIC NOTES a visual representation of self CHAD PHILIP HALL 2 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF: master of design university of washington 2016 COMMITTEE: kristine matthews karen cheng linda norlen PROGRAM AUTHORIZED TO OFFER DEGREE: school of art + art history + design, division -

Spotlight on Erie

From the Editors The local voice for news, Contents: March 2, 2016 arts, and culture. Different ways of being human Editors-in-Chief: Brian Graham & Adam Welsh Managing Editor: Erie At Large 4 We have held the peculiar notion that a person or Katie Chriest society that is a little different from us, whoever we Contributing Editors: The educational costs of children in pov- Ben Speggen erty are, is somehow strange or bizarre, to be distrusted or Jim Wertz loathed. Think of the negative connotations of words Contributors: like alien or outlandish. And yet the monuments and Lisa Austin, Civitas cultures of each of our civilizations merely represent Mary Birdsong Just a Thought 7 different ways of being human. An extraterrestrial Rick Filippi Gregory Greenleaf-Knepp The upside of riding downtown visitor, looking at the differences among human beings John Lindvay and their societies, would find those differences trivial Brianna Lyle Bob Protzman compared to the similarities. – Carl Sagan, Cosmos Dan Schank William G. Sesler Harrisburg Happenings 7 Tommy Shannon n a presidential election year, what separates us Ryan Smith Only unity can save us from the ominous gets far more airtime than what connects us. The Ti Summer storm cloud of inaction hanging over this neighbors you chatted amicably with over the Matt Swanseger I Sara Toth Commonwealth. drone of lawnmowers put out a yard sign supporting Bryan Toy the candidate you loathe, and suddenly they’re the en- Nick Warren Senator Sean Wiley emy. You’re tempted to un-friend folks with opposing Cover Photo and Design: The Cold Realities of a Warming World 8 allegiances right and left on Facebook. -

Read Razorcake Issue #27 As A

t’s never been easy. On average, I put sixty to seventy hours a Yesterday, some of us had helped our friend Chris move, and before we week into Razorcake. Basically, our crew does something that’s moved his stereo, we played the Rhythm Chicken’s new 7”. In the paus- IInot supposed to happen. Our budget is tiny. We operate out of a es between furious Chicken overtures, a guy yelled, “Hooray!” We had small apartment with half of the front room and a bedroom converted adopted our battle call. into a full-time office. We all work our asses off. In the past ten years, That evening, a couple bottles of whiskey later, after great sets by I’ve learned how to fix computers, how to set up networks, how to trou- Giant Haystacks and the Abi Yoyos, after one of our crew projectile bleshoot software. Not because I want to, but because we don’t have the vomited with deft precision and another crewmember suffered a poten- money to hire anybody to do it for us. The stinky underbelly of DIY is tially broken collarbone, This Is My Fist! took to the six-inch stage at finding out that you’ve got to master mundane and difficult things when The Poison Apple in L.A. We yelled and danced so much that stiff peo- you least want to. ple with sourpusses on their faces slunk to the back. We incited under- Co-founder Sean Carswell and I went on a weeklong tour with our aged hipster dancing. -

FACT Magazine Music & Art News, Upfront Videos, Free Downloads

FACT magazine: music & art news, upfront videos, free downloads, classic vinyl, competitions, gigs, clubs, festivals & exhibitions - End of year charts: volume 5 04/01/10 19.08 Home News Features Broadcast Blogs Reviews Events Competitions Gallery search... Go Want to advertise? Click here Login Username End of year charts: volume 5 Password 1 FACT music player 2 Friday, 18 December 2009 Remember me Login 3 4 Lost Password? 5 No account yet? Register (2 votes) Open player in pop-up ACTRESS (pictured) 1. Cassablanca – Mzo Bullet [CD-R] Latest FACT mixes 2. Bibio - Ambivalence Avenue [Warp] 3. Keaver & Brause - The Middle Way [Dealmaker] 4. Thriller - Freak For You / Point & Gaze [Thriller] 5. Nathan Fake - Hard Islands [Border Community] 6. Hudson Mohawke - Butter [Warp] 7. The Horrors - Primary Colours [XL] 8. Actress – Ghosts Have a Heaven [Prime Numbers] Follow us on 9. Joy Orbison - Hyph Mngo [Hotflush] 10. Animal Collective - Merriweather Post Pavilion [Domino] 11. Leron Carson - Red Lightbulb Theory '87 - '88 [Sound Signature] 12. Raekwon - Only Built For Cuban Linx 2 [H2o] Last Comments 13. Darkstar - Aidy's Girl's A Computer [Hyperdub] 14. Zomby - Digital Flora [Brainmath] 1. FACT mix 112: Deadboy 15. Thriller – Swarm / Hubble [Thriller] by mosca 16. Peter Broderick - Float [Type] 2. Daily Download: Actress vs... by coxy 17. Rick Wilhite - The Godson EP [Rush Hour] 3. FACT mix 58: Untold 18. The xx - The xx [XL] by beezerholmes 4. 20 albums to look forward to... 19. Rustie – Bad Science [Wireblock] by tomlea 20. Cloaks – Versus Grain [3by3] 5. 100 best: Tracks of 2009 by jonhharris Compiled by Actress (Werk Discs), London, UK. -

Nov./Dec. 2007 VOL.57 TOTAL TIME: 73'37” 01 ANIMAL COLLECTIVE Peacebone TBTF 03 STARS the Night Starts Here 04 the GOOD

01 ANIMAL COLLECTIVE 07 CARIBOU 13 REVEREND & THE MAKERS Peacebone Melody Day Heavyweight Champion of the World (Remix Edit) Nov./Dec. 2007 VOL.57 アニマル・コレクティヴ「ピースボーン」 カリブー「メロディー・デイ」 レヴァランド・アンド・ザ・メイカーズ「ヘヴィウェイト・チャ (Animal Collective)5:14 (Dan Snaith)4:11 ンピオン・オブ・ザ・ワールド(リミックス・エディット)」 taken from the album STRAWBERRY JAM taken from the album ANDORRA (McClure, Cosens, Smith)4:02 [Domino / Hostess]>030 [City Slang / Merge / Hostess]>012 original version is taken from the album THE STATE OF THINGS [Wall Of Sound / Hostess]>018 02 BROKEN SOCIAL SCENE PRESENTS KEVIN DREW 08 BRICOLAGE 14 ENON TBTF Flowers Of Deceit Pigeneration ブロークン・ソーシャル・シーン・プレゼンツ・ ブリコラージュ「フラワーズ・オブ・ディシート」 イーノン「ピージェネレーション」 ケビン・ドリュー「ティービーティーエフ」 (words by Wallace Meek; music by Bricorage) (Enon)3:33 (Kevin Drew)3:50 2:49 taken from the album GRASS GEYSERS... CARBON taken from the album SPIRIT IF... taken from the album BRICOLAGE CLOUDS [Arts & Crafts / Pony Canyon]>022 [Memphis Industries / Kurofune]>090 [Touch And Go / Traffic]>053 03 STARS 09 EIGHT LEGS 15 PINBACK The Night Starts Here Tell Me What Went Wrong From Nothing To Nowhere スターズ「ザ・ナイト・スターツ・ヒア」 エイト・レッグス「テル・ミー・ホワット・ウェ ピンバック「フロム・ナッシング・トゥ・ノーホ (Stars)4:54 ント・ロング」 エア」 taken from the album IN OUR BEDROOM AFTER (words by Sam Jolly; music by Eight Legs)2:32 (The Rob And Zach Show)3:28 THE WAR taken from the album SEARCHING FOR THE SIMPLE LIFE taken from the album AUTUMN OF THE SERAPHS [Arts & Crafts / Pony Canyon]>026 [Weekender / Kurofune]>088 [Touch And Go / Traffic]>050 04 THE GOOD LIFE 10 JEAN-MICHEL 16 LIARS You Don’t Feel -

Bookstore Blues

Jacksonville State University JSU Digital Commons Chanticleer Historical Newspapers 2007-09-13 Chanticleer | Vol 56, Issue 3 Jacksonville State University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.jsu.edu/lib_ac_chanty Recommended Citation Jacksonville State University, "Chanticleer | Vol 56, Issue 3" (2007). Chanticleer. 1479. https://digitalcommons.jsu.edu/lib_ac_chanty/1479 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Historical Newspapers at JSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Chanticleer by an authorized administrator of JSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. I Volume 56, Issue 3 * . Banner may be toI . blame for mis'sing checks JSU remembers 911 1, By Brandon Hollingsworth was not in the mailbox," Ellis said. confirmed that students who d~dnot six years later. News Editor "So I go the financial aid office to get their checks would have to wait Story on ge, make an inqu~ry." for manual processing to sort through Many JSU students received finan- There, Ellis said, workers told the delay. cia1 aid refund checks on Monday, him that due to a processing glitch, Adams indicated that JSU's new Sept. 10. his check would not be ready until Banner system is partly responsible SGA President David Some put the mmey in the bank, Wednesday, Sept. 12. for the problem. Jennings joins other sofrle spent it on booka, some on At the earl~est. "There were some lssues ~n the, student presidents in less savory expen&we$. , Another student, Kim Stark, was [older] Legacy system," Adams said, an effort to fight book However, some students, mostly tdd to Walt up to two weeks for her "But with the new Banner system, prices. -

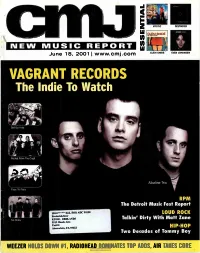

VAGRANT RECORDS the Lndie to Watch

VAGRANT RECORDS The lndie To Watch ,Get Up Kids Rocket From The Crypt Alkaline Trio Face To Face RPM The Detroit Music Fest Report 130.0******ALL FOR ADC 90198 LOUD ROCK Frederick Gier KUOR -REDLANDS Talkin' Dirty With Matt Zane No Motiv 5319 Honda Ave. Unit G Atascadero, CA 93422 HIP-HOP Two Decades of Tommy Boy WEEZER HOLDS DOWN el, RADIOHEAD DOMINATES TOP ADDS AIR TAKES CORE "Tommy's one of the most creative and versatile multi-instrumentalists of our generation." _BEN HARPER HINTO THE "Geggy Tah has a sleek, pointy groove, hitching the melody to one's psyche with the keen handiness of a hat pin." _BILLBOARD AT RADIO NOW RADIO: TYSON HALLER RETAIL: ON FEDDOR BILLY ZARRO 212-253-3154 310-288-2711 201-801-9267 www.virginrecords.com [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] 2001 VIrg. Records Amence. Inc. FEATURING "LAPDFINCE" PARENTAL ADVISORY IN SEARCH OF... EXPLICIT CONTENT %sr* Jeitetyr Co owe Eve« uuwEL. oles 6/18/2001 Issue 719 • Vol 68 • No 1 FEATURES 8 Vagrant Records: become one of the preeminent punk labels The Little Inclie That Could of the new decade. But thanks to a new dis- Boasting a roster that includes the likes of tribution deal with TVT, the label's sales are the Get Up Kids, Alkaline Trio and Rocket proving it to be the indie, punk or otherwise, From The Crypt, Vagrant Records has to watch in 2001. DEPARTMENTS 4 Essential 24 New World Our picks for the best new music of the week: An obit on Cameroonian music legend Mystic, Clem Snide, Destroyer, and Even Francis Bebay, the return of the Free Reed Johansen. -

Current, September 10, 2012

University of Missouri, St. Louis IRL @ UMSL Current (2010s) Student Newspapers 9-10-2012 Current, September 10, 2012 University of Missouri-St. Louis Follow this and additional works at: https://irl.umsl.edu/current2010s Recommended Citation University of Missouri-St. Louis, "Current, September 10, 2012" (2012). Current (2010s). 114. https://irl.umsl.edu/current2010s/114 This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Newspapers at IRL @ UMSL. It has been accepted for inclusion in Current (2010s) by an authorized administrator of IRL @ UMSL. For more information, please contact [email protected]. September 10, 2012 Vol. 46 Issue 1383 News 3 Features 4 Gallery 210 hosts a winning set of A&E 5 exhibits to kick off its fall season Opinions 6 GARRETT KING music and culture. associate professor of art and art history Phillip included sculpture, silk-screens, sketches, As is typical of Gallery 210’s receptions, the Robinson and professor of art and art history photography and even a graphic design portfolio. Staff Writer Comics 8 artists whose pieces were on display came to join Ken Anderson (all UMSL faculty presenting their Douglas stuck to mediums like enamel paint Gallery 210, University of Missouri – St. Louis’ in the festivities and field the questions of 210’s work for the Jubilee) were also present, as was and graphite, Alvarez used paper and mixed resident exporter of St. Louis art and culture, eager patrons. Arny Nadler, the sculptor behind “Whelm.” media and Corley employed cardstock, string and Mon kicked off its fall season on September 6 with a Thursday’s reception welcomed Deb Douglas, The artists’ work varied immensely. -

Aller 210 Hosts a Wi Ning Set 0 Exhib Ets to Kick Off Its All Season

UMSL's independent student news September 10, 2012 Vol. 46 Issue 1383 News ................... 3 0 Features .......... 4 aller 210 hosts a wi ning set A&E ........................ 5 exhib ets to kick off its all season Opinions........ :6 GARRETT KING music and culture. associate professor of art and art history Phillip included sculpture, silk-screens, sketches, Staff Writer As is typical of Gallery 21O's receptions, the Robinson and professor of art and art history photography and even a graphic design portfolio. Comics .............. 8 artists whose pieces were on display came to join Ken And'erson (all UMSL faculty presenting their Douglas stuck to mediums like enamel paint Gallery 210, University of Missouri - St. Louis' in the festivities and field the Questions of 21O's work for the Jubilee) were also present, as was and graph ite, Alvarez used paper and mixed resident exporter of St. L0uis art and culture, eager patrons. Arny Nadler, the sculptor behind "Whelm." media and Corley employed cardstock , string and Mon kicked off its fall season on September 6 with a Thursday's reception welcomed Deb Douglas, The artists' work varied immensely. For dye. Each artist's work communicated different public reception. The gallery's latest Heather Corley and Gina Alvarez, who presented "Expsoure 15," Douglas's work featured blown up themes. Dou glas prefers to capture such additions ~ "Exposure 15," the UMSL Faculty their work in "Exposure 15 ." Professor of collages; Corley had a un ique sculptural piece abstraction s as nostal gia , rel ationsh ips and Jubilee and "Whelm" (the large metal sculpture photography, Dan Younger, associate professor called "Certain Uncertainty," which took pattern in her wo rk. -

Canvas 06 Music.Pdf

THE MUSIC ISSUE ALTER I think I have a pretty cool job as and design, but we’ve bridged the editor of an online magazine but gap between the two by including PAGE 3 if I could choose my dream job some of our favourite bands and I’d be in a band. Can’t sing, can’t artists who are both musical and play any musical instrument, bar fashionable and creative. some basic work with a recorder, but it’s still a (pipe) dream of mine We have been very lucky to again DID I STEP ON YOUR TRUMPET? to be a front woman of some sort work with Nick Blair and Jason of pop/rock/indie group. Music is Henley for our editorials, and PAGE 7 important to me. Some of my best welcome contributing writer memories have been guided by a Seema Duggal to the Canvas song, a band, a concert. I team. I met my husband at Livid SHAKE THAT DEVIL Festival while watching Har Mar CATHERINE MCPHEE Superstar. We were recently EDITOR PAGE 13 married and are spending our honeymoon at the Meredith Music Festival. So it’s no surprise that sooner or later we put together a MUSIC issue for Canvas. THE HORRORS This issue’s theme is kind of a departure for us, considering we PAGE 21 tend to concentrate on fashion MISS FITZ PAGE 23 UNCOVERED PAGE 28 CREATIVE DIRECTOR/FOUNDER CONTRIBUTING PHOTOGRAPHERS Catherine McPhee NICK BLAIR JASON HENLEY DESIGNER James Johnston COVER COPYRIGHT & DISCLAIMER EDITORIAL MANAGER PHOTOGRAPHY Nick Blair Reproduction in whole or in part without written permission by Canvas is strictly prohibited.