A Green Infrastructure Plan for Norfolk: BUILDING RESILIENT COMMUNITIES

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

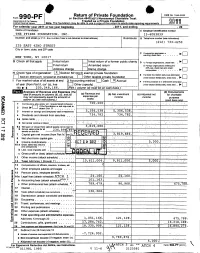

Return of Private Foundation CT' 10 201Z '

Return of Private Foundation OMB No 1545-0052 Form 990 -PF or Section 4947(a)(1) Nonexempt Charitable Trust Department of the Treasury Treated as a Private Foundation Internal Revenue Service Note. The foundation may be able to use a copy of this return to satisfy state reporting requirem M11 For calendar year 20 11 or tax year beainnina . 2011. and ending . 20 Name of foundation A Employer Identification number THE PFIZER FOUNDATION, INC. 13-6083839 Number and street (or P 0 box number If mail is not delivered to street address ) Room/suite B Telephone number (see instructions) (212) 733-4250 235 EAST 42ND STREET City or town, state, and ZIP code q C If exemption application is ► pending, check here • • • • • . NEW YORK, NY 10017 G Check all that apply Initial return Initial return of a former public charity D q 1 . Foreign organizations , check here . ► Final return Amended return 2. Foreign organizations meeting the 85% test, check here and attach Address chang e Name change computation . 10. H Check type of organization' X Section 501( exempt private foundation E If private foundation status was terminated Section 4947 ( a)( 1 ) nonexem pt charitable trust Other taxable p rivate foundation q 19 under section 507(b )( 1)(A) , check here . ► Fair market value of all assets at end J Accounting method Cash X Accrual F If the foundation is in a60-month termination of year (from Part Il, col (c), line Other ( specify ) ---- -- ------ ---------- under section 507(b)(1)(B),check here , q 205, 8, 166. 16) ► $ 04 (Part 1, column (d) must be on cash basis) Analysis of Revenue and Expenses (The (d) Disbursements total of amounts in columns (b), (c), and (d) (a) Revenue and (b) Net investment (c) Adjusted net for charitable may not necessanly equal the amounts in expenses per income income Y books purposes C^7 column (a) (see instructions) .) (cash basis only) I Contribution s odt s, grants etc. -

Springhill Suites Norfolk Virginia Beach Attractions

Attractions Nearby Outdoor Adventure • Stop and smell the roses at the Norfolk Botanical Garden • Walk along the path inside a Kangaroo exhibit at the Virginia Zoo • Stroll along the famous 3-mile boardwalk right beside the Atlantic Ocean, or stop by one of the many unique shops and variety of restaurants along the way. With Festivals, events, and outdoor concerts, there’s always something to do at the Virginia Beach Oceanfront. Entertainment and Nightlife • Try one of the many eclectic restaurants and bars in the historic Ghent District, or enjoy a drink and an appetizer along the inlet at the nearby Waterside District. • Plan a visit to the Chrysler Museum of Art • Hop on the Tide Light Rail to take you to Chrysler Hall, the official Performing Arts Center of Hampton Roads. • Learn all about maritime history, science, technology, sailing, and even discover the history behind our famous Battleship Wisconsin all in one place. Enjoy a self-guided tour, or explore the fascinating Admiral’s cabin, Combat Engagement Center, Captain’s Cabin, and more with the Guided Command & Control Tour. • Step foot into history at the Hampton Roads Naval Museum • Norfolk Premium Outlets • Stroll through streets lined with murals, join in an improv comedy show, watch live glass blowing, and more at the nearby Neon District. Sports and Recreation • In the heart of Norfolk lies the world’s largest reinforced thin-shell concrete dome, Scope Arena. Home of the MEAC Basketball Tournament, concerts, shows, and more- this arena can accommodate everyone’s style of entertainment. • Home of Old Dominion University Athletics, the Ted Constant Convocation Center hosts everything from sporting events, to concerts, comedy shows, and career fairs. -

The RUNDOWN the RUNDOWN

July 2008 Edition TheThe RUNDOWNRUNDOWN Monthly newsletter of the TIDEWATER STRIDERS Running Club. One of the nation’s largest running organizations. New Membership & Newsletter Rates Start July 1st The Tidewater Striders will commence phasing in a conversion plan to email dis- tribution of the club’s newsletter. Bowing to escalating printing & bulk mail costs and the strong desire to “Go Green” your Board has approved new membership rates which reward those opting for email delivery of The Rundown and sets rates that will cover the cost of paper copies and bulk mail for those who select the postal service deliv- ery option. These will be phased in over the next few months. The new rates are effec- tive July 1st for new members and those renewing. Eventually all requiring paper deliver will need to advise the membership chairman. The new application is inside the back cover of this Rundown. Please encourage your friends and family members to join the Tidewater Striders by passing on this Run- down and application. The Summer Series is a great time to join the Striders and meet many members along with having a great time in the heat of the summer. Upcoming Striders’ Events Member of • Tuesday, July 8, 2008 - Summer Series Countdown 4 Miler • Tuesday, July 15, 2008 - Summer Series 3x2k Relay • Tuesday, July 15, 2008 - Rundown Deadline • Tuesday, July 15, 2008 - Rundown Deadline • Saturday, July 19, 2008 - Allen Stone Run-Swim-Run & 5k • Tuesday, July 29, 2008 - Memorial 5k • Thursday, July 31, 2008 - Newsletter Stuffi ng 2008 Summer Series at the Garden A Tidewater Striders fun run event Place: The Norfolk Botanical Garden, on Azalea Garden Road, near the Norfolk International Airport. -

Norfolk Theatre Festival Fall in Love with Theatre! February 14 – 17, 2019

Norfolk Announces a Theatre Celebration! Norfolk Theatre Festival Fall in love with theatre! February 14 – 17, 2019 Norfolk is one of the most theatre-rich cities in Virginia, a diverse community full of spirited audiences in venues large and small. February 14-17, the Norfolk Theatre Festival will mark Norfolk’s role as a cultural destination and celebrate the performing arts organizations that enliven the scene here. “As the arts and culture destination of Hampton Roads, Norfolk is excited to bring the highest caliber of theatrical performances to our city for residents, visitors and the community to celebrate,” said Norfolk Mayor Kenneth Cooper Alexander. Norfolk is home to a gifted performing arts community, vibrant theatre companies, multiple universities with theatre programs, and a nurturing environment for new works. Norfolk also hosts a robust touring Broadway series which draws tens of thousands of residents and regional visitors per season. In addition, the venues that house some of the liveliest performances in Norfolk are among the most beautiful and historic places in this architecturally distinguished city. Experience unforgettable shows, behind-the-scenes events, and more. Discover the riches of the Norfolk theatre scene in a whirlwind weekend in February 2019—the perfect Valentine’s getaway or staycation! Performances during Norfolk Theatre Festival include: Once On This Island presented by Norfolk State University Theatre Company Thursday, February 14, 7:30pm Saturday, February 16, 2:00pm Sunday, February 17, 2:00pm Norfolk State University's G.W.C. Brown Memorial Hall Mainstage Theater Once On This Island is the big, bold and breathtaking tale of Ti Moune, a fearless Caribbean girl who is ready to risk it all for love. -

Guide to the Merrimac & Monitor Post Card Company “Virginia in Dry

Guide to the Merrimac & Monitor Post Card Company “Virginia in Dry Dock” Postcard, 1906 MS0429 The Mariners' Museum Library at Christopher Newport University Contact Information: The Mariners' Museum Library 100 Museum Drive Newport News, VA 23606 Phone: (757) 591-7782 Fax: (757) 591-7310 Email: [email protected] URL: www.MarinersMuseum.org/library Processed by Jay E. Moore, 2012 DESCRIPTIVE SUMMARY Repository: The Mariners' Museum Library Title: Merrimac & Monitor Post Card Company “Virginia in Dry Dock” Postcard Inclusive Dates: 1906 Catalog number: MS0429 Physical Characteristics: 1 picture postcard Language: English Creator: Merrimac & Monitor Post Card Company (Firm); Richardson, Benjamin A. (Benjamin Adworth) HISTORICAL SKETCH The Merrimac & Monitor Post Card Company was formed in 1906 with the immediate purpose of issuing commemorative postcards to be sold during the Jamestown Tercentenary celebration in 1907. The company produced postcards commemorating the events of Mar.8 and 9, 1862 during the Battle of Hampton Roads. It also created postcards pertaining to the life of CSS Virginia. They range from the April 19, 1861 destruction at the Gosport Navy Yard of the US steam frigate Merrimack, from whose hulk Virginia was built, to the destruction of the ironclad on the shores of Craney Island, Virginia, on May 10-11, 1862 at the hands of its own crew. The paintings on the postcards were taken from a series of original works by Benjamin A. Richardson (1833-1909). Richardson, born in Portsmouth, was a self-taught, amateur artist. Early in life, he earned a living as a house and sign painter. During the Civil War, Richardson enlisted in Norfolk as a private in the Confederate States Army in the United Artillery under Captain Thomas Kevill. -

Native Plants for Southeast Virginia, Including Hampton Roads Region

Native Plants for Southeast Virginia including Hampton Roads Region Plant Southeast Virginia Natives! This guide showcases the attractive variety of plants native to Southeast Virginia, which includes the Hampton Roads region. Native plant species have evolved within specific areas and been dispersed throughout their range without known human involvement. These plants form the primary structure of the living landscape and provide food and shelter for native animal species. Although this guide is not comprehensive, the native plants featured here were selected because they are attractive, relatively easy for the home gardener to acquire, easy to maintain, and offer Swamp Milkweed (Asclepias incarnata) and Eastern Tiger Swallowtail (Papilio glaucus) various benefits to wildlife and the environment. This guide is being provided by the Hampton Roads organizations listed below to promote the use of these plants in the urban and suburban landscapes of Southeast Virginia for their many social, cultural, and economic benefits, and to increase the availability of these native plants in retail centers throughout the region. Butterfly Society of Virginia Master Gardeners Virginia Natural Heritage Program/VA Chesapeake Bay Foundation Master Naturalists Dept of Conservation and Recreation Eco Images Meg French Design Virginia Institute of Marine Science Elizabeth River Project Norfolk Botanical Garden Virginia Living Museum Hampton Roads Planning District Sassafras Farm Virginia State Beekeepers Association Commission - HR STORM, HR WET South Hampton Roads Chapter, VNPS Virginia Tech Hampton Roads AREC Hermitage Museum and Gardens Southern Branch Nursery Wetlands Watch John Clayton Chapter, VNPS York County Wild Works of Whimsy Keep Norfolk Beautiful Virginia Coastal Zone Management Lynnhaven River Now Program/VA Dept of Environmental Quality Design and publication management by Virginia Witmer, Coastal Zone Management Program. -

Opportunity Zone Prospectus

NORFOLK ® OPPORTUNITY ZONE PROSPECTUS N O R F O L K V I R G I N I A - I N V E S T M E N T P R O S P E C T U S 1 WELCOME For more than 300 years, Norfolk has served as the cultural and economic heart of Hampton Roads, mixing ideas, connecting people, creating new experiences and new businesses, and powering the growth of a region that is home to 1.75 million people and a real GDP approaching $84 billion. One of America’s oldest global trade destinations, Norfolk has been transformed into a global center for international security and coastal resilience. We are home to Naval Station Norfolk, the world’s largest naval base, and NATO’s only headquarters in North America. We also serve as a national leader in health care, transportation, higher education, and visual and performing arts. Norfolk is investing in transformative projects that will enhance our assets, foster inclusive economic growth, and develop talented and motivated residents. In 2018, we launched the transformation of the St. Paul’s Area, which will reshape three public housing communities that encompass more than 200 acres near our thriving downtown. Investments in the people, physical infrastructure, and anchor institutions that are native to this area are helping us to attract new businesses and entrepreneurs that will drive regional productivity and growth. The neighborhoods of the St. Paul’s Area are just one example of the 16 qualified opportunity zones, the most of any city or county in the Commonwealth of Virginia, that we hope you will consider for investment. -

American Beech

Conservation Gap Analysis of American Beech August 2021 Emily Beckman1, Abby Meyer2, David Pivorunas3, Sean Hoban1 and Murphy Westwood1,4 1The Morton Arboretum 2Botanic Gardens Conservation International, U.S. 3USDA Forest Service 4Botanic Gardens Conservation International Fagus grandifolia Ehrh. (American beech) THE MORTON ARBORETUM is an internationally recognized outdoor tree museum and tree research center located in Lisle, Illinois. As the champion of trees, the Arboretum is committed to scientifically informed action, both locally and globally, and encouraging the planting and conservation of trees for a greener, healthier, more beautiful world. The Morton Arboretum welcomes more than 1.3 million visitors annually to explore its 1,700 acres with 222,000 plant specimens representing 4,650 different kinds of plants. The Arboretum’s Global Tree Conservation Program works to prevent tree extinctions around the world by generating resources, fostering cross-sector collaborations, and engaging local partners in conservation projects. The Center for Tree Science seeks to create the scientific knowledge and technical expertise necessary to sustain trees, in all their diversity, in built environments, natural landscapes, and living collections. The Arboretum also hosts and coordinates ArbNet, the interactive, collaborative, international community of arboreta and tree-focused professionals. BOTANIC GARDENS CONSERVATION INTERNATIONAL ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS (BGCI) is the world’s largest plant conservation network, comprising more than 600 botanic gardens in over 100 countries, and provides First and foremost, many thanks to the hundreds of institutions who the secretariat to the IUCN/SSC Global Tree Specialist Group. BGCI shared their ex situ accessions data and/or reported conservation was established in 1987 and is a registered charity with offices in activities. -

The Colonial Master Gardener May

The Colonial Master Gardener May PUBLICATION OF JCC/WMASTER GARDENER ASSO C I A T I O N & 2015 VIRGINIA COOPERATIVE EXTENSION THE PRESIDENT’S MESSAGE Next Meeting: BY SUE LIDDELL Thursday, May 7 We took advantage of the warmer weather in April by offering Program: various programs, including garden symposiums, tours, and plant Ira Wallace sales. During tours of Colonial Williamsburg as part of Garden “Heirlooms, Seed Saving, and Threats from GMOs” Week, leaders talked about garden design and how participants could get ideas for their own gardens. This made me think about what kind of garden I have and, more the pizza garden we put in last year. This month we importantly, what kind of gardener I am. After I’d lived here a few will add tomatoes, peppers, and onions to the patch. years, I made a list of all the plants on my property and plotted out a rough landscape design. For a few years I kept this up, Whatever kind of gardener you are, thanks for sharing moving, adding, and subtracting plants, and recording the your knowledge and experience through our MG changes. I still move, add, and subtract plants, but I no longer organization. keep a record. As a result I have decided I am a Continually Surprised Gardener. I have had beautiful primroses one year, never to be seen again. I have enjoyed a ground cover with variegated leaves, which I believe is Lamium. This year is the first year it is covered with flowers. I have a Yucca that blooms every three to four years. -

Winter 2019 Eric Carle Illustration for Panda Bear, Panda Bear, What Do You See? by Bill Martin, Jr

winter 2019 Eric Carle Illustration for Panda Bear, Panda Bear, What Do You See? by Bill Martin, Jr. Collection of Eric and Barbara Carle © 2003 Eric Carle Save the Date June 14–September 8, 2019 Scholarship and Innovation This fall, the Chrysler Museum of Art will present Thomas Jefferson, Architect: Palladian Models, Democratic Principles, and the Conflict of Ideals. It will be the first of several major exhibitions organized by the Chrysler Museum’s curatorial team. We aim to mark the Chrysler as a producer of original content and new ideas that will raise our national profile. This ambitious revitalization of the exhibition program will prioritize the skills and knowledge of our staff and bring great art to our community in fresh and compelling ways. Thomas Jefferson, Architect is a partnership with the Palladio Museum in Vicenza, Italy. It is the first major exhibition on Jefferson’s design practice since the 1970s and incorporates a wealth of new scholarship that confronts his desire to convey ideals of liberty and democracy while creating monuments that were founded on the economic and social institution of slavery. In upcoming seasons, the Chrysler will present Alma W. Thomas: A Creative Life, Americans in Spain, and Jacob Lawrence. The exhibitions are led by Chrysler curators, some in collaboration with a curator from a peer institution, and are intended to travel to other museums. A catalog with new scholarship will accompany each exhibition. Developing exhibitions in-house is not unprecedented at the Chrysler. In 2015, we presented Tseng Kwong Chi: Performing for the Camera. It traveled to three other museums and was accompanied by a catalog with new critical essays. -

Anna Holloway Image Collection on Ironclad Warships, 1889-1911 MS0438

Guide to the Anna Holloway Image Collection on Ironclad Warships, 1889-1911 MS0438 The Mariners' Museum Library at Christopher Newport University Contact Information: The Mariners' Museum Library 100 Museum Drive Newport News, VA 23606 Phone: (757) 591-7782 Fax: (757) 591-7310 Email: [email protected] URL: www.mariner.org/library Processed by Johanna Quinn, 2010 DESCRIPTIVE SUMMARY Repository: The Mariners' Museum Library Title: Anna Holloway Image Collection on Ironclad Warships Inclusive Dates: 1889-1911 Catalog number: MS0438 Physical Characteristics: 11 items, including cigarette cards, advertising cards, picture postcards and stereographs Language: English Creator: Holloway, Anna Gibson BIOGRAPHICAL SKETCH Anna Gibson Holloway is the Vice President of Museum Collections and Programs at The Mariners’ Museum in Newport News, VA where she oversees the Curatorial, Collections Management, Education, Conservation and Exhibition Design functions of the Museum. She also serves as curator of the USS Monitor Center and in that role, won the American Association of Museum’s Award for the Best Exhibition of 2007. Before the cheesebox on a raft entered her life, she was the Director of Education and Resident Pirate at The Mariners’ Museum, then Chief Curator. In the waning years of the 20th century, she was Manager of School Tour Programs for the Chrysler Museum of Art in Norfolk, VA and has also worked for Jamestown Settlement as part of the crew of the Susan Constant, and for the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation where she was a puppeteer and understudy fire eater. This Winston-Salem native graduated from The University of North Carolina at Greensboro with baccalaureate degrees in English Literature and Medieval Civilization, neither of which was very helpful in fulfilling her goal of being a rock star. -

Theaters and Performing Arts Companies in Hampton Roads

Theaters & Performing Arts Companies THE PLAY’S THE THING: THEATERS AND PERFORMING ARTS COMPANIES IN HAMPTON ROADS ll of Hampton Roads is but a stage and the theater companies merely players that strut across it. Yet, what a stage it is! The area’s companies provide a rich menu of thought-provoking and entertaining productions, all of which enhance Athe region with vital cultural and economic benefits. The vibrant community of thespians in Hampton Roads premiered in the late 19th and early 20th centuries at venues like The Academy of Music, and the American, the Colonial and the Wells theaters, where vaudeville mixed with drama and the emerging moving picture amusements. In fact, in the early days of the 20th century, Norfolk was viewed as the cultural “gateway to the south.” A brief decline into adult entertainment occurred in several of these theaters during the middle of the 20th century, followed by a slow and deliberate emergence into a healthy and engaging theatrical life. Currently, the theatrical venues of Hampton Roads boast several major professional companies, a changing plate of smaller com- munity performing companies, and a host of universities and colleges stretching the diversity of dramatic selections. Whether sup- ported by magnanimous corporate sponsorship, dedicated avocational passions or the hobby of a few rich patrons of the arts, local theater contributes significantly to the revitalization of Hampton Roads communities. THE WELLS THEATRE Since opening in 1913, the historic landmark New Wells Theatre welcomed guests into an ornate and exquisite venue of beaux-arts classicism, originally seating 1,650 with a top balcony “For Negro Audiences Only.” It once featured “Ben Hur,” with chariots on treadmills, and hosted the likes of Fred and Adele Astaire, Will Rogers and John Philip Sousa.