Wile E. Coyote and Other Sly Trickster Tales

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Top Hugo Nominees

Top 2003 Hugo Award Nominations for Each Category There were 738 total valid nominating forms submitted Nominees not on the final ballot were not validated or checked for errors Nominations for Best Novel 621 nominating forms, 219 nominees 97 Hominids by Robert J. Sawyer (Tor) 91 The Scar by China Mieville (Macmillan; Del Rey) 88 The Years of Rice and Salt by Kim Stanley Robinson (Bantam) 72 Bones of the Earth by Michael Swanwick (Eos) 69 Kiln People by David Brin (Tor) — final ballot complete — 56 Dance for the Ivory Madonna by Don Sakers (Speed of C) 55 Ruled Britannia by Harry Turtledove NAL 43 Night Watch by Terry Pratchett (Doubleday UK; HarperCollins) 40 Diplomatic Immunity by Lois McMaster Bujold (Baen) 36 Redemption Ark by Alastair Reynolds (Gollancz; Ace) 35 The Eyre Affair by Jasper Fforde (Viking) 35 Permanence by Karl Schroeder (Tor) 34 Coyote by Allen Steele (Ace) 32 Chindi by Jack McDevitt (Ace) 32 Light by M. John Harrison (Gollancz) 32 Probability Space by Nancy Kress (Tor) Nominations for Best Novella 374 nominating forms, 65 nominees 85 Coraline by Neil Gaiman (HarperCollins) 48 “In Spirit” by Pat Forde (Analog 9/02) 47 “Bronte’s Egg” by Richard Chwedyk (F&SF 08/02) 45 “Breathmoss” by Ian R. MacLeod (Asimov’s 5/02) 41 A Year in the Linear City by Paul Di Filippo (PS Publishing) 41 “The Political Officer” by Charles Coleman Finlay (F&SF 04/02) — final ballot complete — 40 “The Potter of Bones” by Eleanor Arnason (Asimov’s 9/02) 34 “Veritas” by Robert Reed (Asimov’s 7/02) 32 “Router” by Charles Stross (Asimov’s 9/02) 31 The Human Front by Ken MacLeod (PS Publishing) 30 “Stories for Men” by John Kessel (Asimov’s 10-11/02) 30 “Unseen Demons” by Adam-Troy Castro (Analog 8/02) 29 Turquoise Days by Alastair Reynolds (Golden Gryphon) 22 “A Democracy of Trolls” by Charles Coleman Finlay (F&SF 10-11/02) 22 “Jury Service” by Charles Stross and Cory Doctorow (Sci Fiction 12/03/02) 22 “Paradises Lost” by Ursula K. -

Kgb Fantastic Fiction Online Raffle

KGB FANTASTIC FICTION ONLINE RAFFLE Press Release For Immediate Release Contacts: Ellen Datlow, KGB co-host, [email protected] , Matthew Kressel, KGB co-host, [email protected] , Mary Robinette Kowal, raffle consultant, [email protected] The Hosts of KGB Fantastic Fiction will raffle off donations from well-known authors, editors, artists, and agents to help support the reading series. Event takes place from July 14 th , 2008 through July 28 th , 2008. Raffle tickets will be $1 each and can be purchased from www.kgbfantasticfiction.org New York, NY (July 2008) – The hosts of the KGB Fantastic Fiction reading series in New York City are holding a raffle to help support the series. Well-known artists and professionals have donated prizes (see Partial List of Prizes below) which will be raffled off in July. All proceeds from the raffle will go to support the reading series, which has been a bright star in the speculative fiction scene for more than a decade. Raffle tickets will cost one dollar US ($1) and can be purchased at www.kgbfantasticfiction.org . You may purchase as many tickets as you want. Tickets will be available from July 14 th , 2008 through July 28 th , 2008. At midnight on July 28 th , raffle winners will be selected randomly for each item and announced on the web. Prizes will be mailed to the lucky winners. (See a more detailed explanation in Raffle Rules ). Partial List of Prizes (a full list is available at the website) • Story in a bottle by Michael Swanwick • Tuckerization (your name in a story) by Lucius Shepard • Tuckerization by Elizabeth Hand • Tuckerization by Jeffrey Ford • Pen & Ink drawing of an animal-your choice- by Gahan Wilson • Original art for a George R. -

THE 2016 DELL MAGAZINES AWARD This Year’S Trip to the International Conference on the Fantastic in the Arts Was Spent in a Whirl of Activity

EDITORIAL Sheila Williams THE 2016 DELL MAGAZINES AWARD This year’s trip to the International Conference on the Fantastic in the Arts was spent in a whirl of activity. In addition to academic papers, author readings, banquets, and the awards ceremony, it was a celebration of major life events. Thursday night saw a surprise birthday party for well-known SF and fantasy critic Gary K. Wolfe and a compelling memorial for storied editor David G. Hartwell. Sunday morning brought us the beautiful wedding of Rebecca McNulty and Bernie Goodman. Rebecca met Bernie when she was a finalist for our annual Dell Magazines Award for Undergraduate Ex- cellence in Science Fiction and Fantasy Writing several years ago. Other past finalists were also in attendance at the conference. In addition to Re- becca, it was a joy to watch E. Lily Yu, Lara Donnelly, Rich Larson, and Seth Dickin- son welcome a brand new crop of young writers. The winner of this year’s award was Rani Banjarian, a senior at Vanderbilt University. Rani studied at an international school in Beirut, Lebanon, before coming to the U.S. to attend college. Fluent in Arabic and English, he’s also toying with adding French to his toolbox. Rani is graduating with a duel major in physics and writing. His award winning short story, “Lullabies in Arabic” incorporates his fascination with memoir writing along with a newfound interest in science fiction. My co-judge Rick Wilber and I were once again pleased that the International Association for the Fantastic in the Arts and Dell Magazines cosponsored Rani’s expense-paid trip to the conference in Orlando, Florida, and the five hundred dollar prize. -

Fantasy Illustration As an Expression of Postmodern 'Primitivism': the Green Man and the Forest Emily Tolson

Fantasy Illustration as an Expression of Postmodern 'Primitivism': The Green Man and the Forest Emily Tolson , Thesis presented in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Fine Arts at the University of Stellenbosch. Supervisor: Lize Van Robbroeck Co-Supervisor: Paddy Bouma April 2006 Stellenbosch University https://scholar.sun.ac.za Dedaratfton:n I, the undersigned, hereby declare that the work contained in this thesis is my own original work and that I have not previously in its entirety or in part submitted it at any Date o~/o?,}01> 11 Stellenbosch University https://scholar.sun.ac.za Albs tract This study demonstrates that Fantasy in general, and the Green Man in particular, is a postmodern manifestation of a long tradition of modernity critique. The first chapter focuses on outlining the history of 'primitivist' thought in the West, while Chapter Two discusses the implications of Fantasy as postmodern 'primitivism', with a brief discussion of examples. Chapter Three provides an in-depth look at the Green Man as an example of Fantasy as postmodern 'primitivism'. The fmal chapter further explores the invented tradition of the Green Man within the context of New Age spirituality and religion. The study aims to demonstrate that, like the Romantic counterculture that preceded it, Fantasy is a revolt against increased secularisation, industrialisation and nihilism. The discussion argues that in postmodernism the Wilderness (in the form of the forest) is embraced through the iconography of the Green Man. The Green Man is a pre-Christian symbol found carved in wood and stone, in temples and churches and on graves throughout Europe, but his origins and original meaning are unknown, and remain a controversial topic. -

Stormed Fortress 603M Tx.Qxd 6/9/07 15:25 Page Ii

603M_tx.qxd 6/9/07 15:25 Page i Stormed Fortress 603M_tx.qxd 6/9/07 15:25 Page ii Books by Janny Wurts Sorcerer’s Legacy The Master of Whitestorm The Wars of Light and Shadow The Cycle of Fire Trilogy That Way Lies Camelot The Curse of the Mistwraith Stormwarden The Ships of Merior Keeper of the Keys Warhost of Vastmark Shadowfane Fugitive Prince Grand Conspiracy Peril’s Gate Traitor’s Knot Stormed Fortress To Ride Hell’s Chasm With Raymond E. Feist Daughter of the Empire Servant of the Empire Mistress of the Empire 603M_tx.qxd 6/9/07 15:25 Page iii Janny Wurts STORMED FORTRESS The Wars of Light and Shadow VOLUME 8 F IFTH B OOK OF THE A LLIANCE OF L IGHT 603M_tx.qxd 6/9/07 15:25 Page iv HarperCollinsPublishers 77–85 Fulham Palace Road, Hammersmith, London W6 8JB www.voyager-books.com Published by HarperVoyager An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers 2007 1 Copyright © Janny Wurts 2007 Janny Wurts asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library ISBN-13: 978-0-00-721780-9 Set in Palatino by Palimpsest Book Production Limited, Grangemouth, Stirlingshire Printed and bound in Great Britain by Clays Ltd, St Ives plc All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publishers. 603M_tx.qxd 6/9/07 15:25 Page v For three, whose enduring commitment to the literature of the fantastic has enriched so many. -

Readercon 14

readercon 14 program guide The conference on imaginative literature, fourteenth edition readercon 14 The Boston Marriott Burlington Burlington, Massachusetts 12th-14th July 2002 Guests of Honor: Octavia E. Butler Gwyneth Jones Memorial GoH: John Brunner program guide Practical Information......................................................................................... 1 Readercon 14 Committee................................................................................... 2 Hotel Map.......................................................................................................... 4 Bookshop Dealers...............................................................................................5 Readercon 14 Guests..........................................................................................6 Readercon 14: The Program.............................................................................. 7 Friday..................................................................................................... 8 Saturday................................................................................................14 Sunday................................................................................................. 21 Readercon 15 Advertisement.......................................................................... 26 About the Program Participants......................................................................27 Program Grids...........................................Back Cover and Inside Back Cover Cover -

TABLE of CONTENTS July 1997 Issue 438 Vol

TABLE OF CONTENTS July 1997 Issue 438 Vol. 39 No. 1 30th Year of Publication 18-Time Hugo Winner CHARLES N. BROWN Publisher & Editor-in-Chief MAIN STORIES MARIANNE S. JABLON Sale of TSR Finalized/10 Ghosh Wins Clarke Award/10 Managing Editor Some SF at BookExpo/10 1997 Prix Aurora Nominees/10 FAREN C. MILLER African-American SF Writers Gather/10 CAROLYN F. CUSHMAN Sovereign Buys Sci-Fi Universe/11 Spectrum Becomes Earthlight/11 Editors THE DATA FILE KIRSTEN GONG-WONG Assistant Editor Internet Book War/11 Announcements/11 Readings & Signings/11 EDWARD BRYANT On the Web/11 Award News/11 Publishing News/65 Financial News/65 MARK R. KELLY Worldcon Update/65 Legal News/65 Book News/65 Rights & Options/65 RUSSELL LETSON Publications Received/65 Multi-Media Received/66 Catalogs Received/66 GARY K. WOLFE INTERVIEWS Contributing Editors JONATHAN STRAHAN Joe Haldeman: Forever War & Peace/6 Visiting Editor Eric S. Nylund: Writing Down the Middle/8 WILLIAM G. CONTENTO INTERNATIONAL Special Projects SF in Brazil/36 SF in Australia/37 SF in Scandinavia/38 BETH GWINN Photographer CONVENTION Locus, The Newspaper of the S cience Fiction Field (ISSN World Horror Convention: 1997/39 0047-4959), is published monthly, at $4.50 per copy, by Locus Publications, 34 Ridgewood Lane, Oakland CA 94611.'Please send all mail to: Locus Publications, P.O. OBITUARIES Box 13305, Oakland CA 94661. Telephone (510) 339- 9196; (510) 339-9198. FAX (510) 339-8144. E-mail: George Turner/62 [email protected]. Individual subscriptions in the US: $43.00 for 12 issues, $80.00 for 24 issues via peri George Turner: Appreciations by Peter Nicholls, Russell Letson, John Douglas/62 odical mail. -

Lightspeed Magazine, Issue 66 (November 2015)

TABLE OF CONTENTS Issue 66, November 2015 FROM THE EDITOR Editorial, November 2015 SCIENCE FICTION Here is My Thinking on a Situation That Affects Us All Rahul Kanakia The Pipes of Pan Brian Stableford Rock, Paper, Scissors, Love, Death Caroline M. Yoachim The Light Brigade Kameron Hurley FANTASY The Black Fairy’s Curse Karen Joy Fowler When We Were Giants Helena Bell Printable Toh EnJoe (translated by David Boyd) The Plausibility of Dragons Kenneth Schneyer NOVELLA The Least Trumps Elizabeth Hand NOVEL EXCERPTS Chimera Mira Grant NONFICTION Artist Showcase: John Brosio Henry Lien Book Reviews Sunil Patel Interview: Ernest Cline The Geek’s Guide to the Galaxy AUTHOR SPOTLIGHTS Rahul Kanakia Karen Joy Fowler Brian Stableford Helena Bell Caroline M. Yoachim Toh EnJoe Kameron Hurley Kenneth Schneyer Elizabeth Hand MISCELLANY Coming Attractions Upcoming Events Stay Connected Subscriptions and Ebooks About the Lightspeed Team Also Edited by John Joseph Adams © 2015 Lightspeed Magazine Cover by John Brosio www.lightspeedmagazine.com Editorial, November 2015 John Joseph Adams | 712 words Welcome to issue sixty-six of Lightspeed! Back in August, it was announced that both Lightspeed and our Women Destroy Science Fiction! special issue specifically had been nominated for the British Fantasy Award. (Lightspeed was nominated in the Periodicals category, while WDSF was nominated in the Anthology category.) The awards were presented October 25 at FantasyCon 2015 in Nottingham, UK, and, alas, Lightspeed did not win in the Periodicals category. But WDSF did win for Best Anthology! Huge congrats to Christie Yant and the rest of the WDSF team, and thanks to everyone who voted for, supported, or helped create WDSF! You can find the full list of winners at britishfantasysociety.org. -

Troll's Eye View

Troll’s Eye View A Book of Villainous Tales Edited by Ellen Datlow and Terri Windling Available only from Teacher’s Junior Library Guild 7858 Industrial Parkway Edition Plain City, OH 43064 www.juniorlibraryguild.com Copyright © 2009 Junior Library Guild/Media Source, Inc. 0 About JLG Guides Junior Library Guild selects the best new hardcover children’s and YA books being published in the U.S. and makes them available to libraries and schools, often before the books are available from anyone else. Timeliness and value mark the mission of JLG: to be the librarian’s partner. But how can JLG help librarians be partners with classroom teachers? With JLG Guides. JLG Guides are activity and reading guides written by people with experience in both children’s and educational publishing—in fact, many of them are former librarians or teachers. The JLG Guides are made up of activity guides for younger readers (grades K–3) and reading guides for older readers (grades 4–12), with some overlap occurring in grades 3 and 4. All guides are written with national and state standards as guidelines. Activity guides focus on providing activities that support specific reading standards; reading guides support various standards (reading, language arts, social studies, science, etc.), depending on the genre and topic of the book itself. JLG Guides can be used both for whole class instruction and for individual students. Pages are reproducible for classroom use only, and a teacher’s edition accompanies most JLG Guides. Research indicates that using authentic literature in the classroom helps improve students’ interest level and reading skills. -

Readercon 2 Flyer

The conference on imaginative literature, second edition F^EADE^corn November 18 - 20, 1988 Lowell Hilton, Lowell, Massachusetts (25 miles northwest of Boston; accessible by public transportation; 508-452-1200) Room rates (per night): $75/single or double, $80/twin, $85/triple, $90/quad (+ 9.7% tax) Membership: $20 now and at the door Guest of Honor: Samuel R. Delany Past Master: Theodore Sturgeon (in memoriam) Algis Budrys David G. Hartwell George Alec Effinger Barry B. Longyear Patricia McKillipw James Patrick Kelly James Morrow Lawrence Watt-Evans Terry Bisson Ellen Kushner Paul Park Terri Windling Richard Bowker Jeffrey Carver Craig Shaw Gardner John Morressy Geary Gravel t*aul Hazel Steven Popkes Darrell Schweitzer Paul DiFilippo Alexander Jablokov 'Elissa Malcohn Susan Palwick Delia Sherman Scott Edelman •.F. Rivkin Charles C. Ryan D. Alexander Smith Kathryn Cramer Martha Millard Joe Shea (Joey Zone) Stanley Wiater Janice M. Eisen Scott E. Green Stan Leventhal Tod Machover Resa Nelson Sarah Smith Bernadette. Bosky Lise Eisenberg Arthur Hlavaty Dr. Vernon ^yles Fred Lerner ... and more to come! “Readercon is the sort of convention all readers of SF should support.” - Gene Wolfe “Pretty much my favorite convention.” - Mark Ziesing ... Judging from the program ... probably the best con in America.” - John Shirley over . (A con flyer that lists its entire prospective program? What better advertising is there?) Main Programming Track Firing the Canon: The Public Perception of F and SF. See Dick Run. See Jane Reveal Depths of the Human Condition: The Juvenile as Literature. The Notion of Lives on Paper: Self and Science Fiction, 1929—1988. -

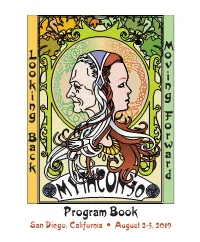

Mythcon 50 Program Book

M L o o v o i k n i g n g F o r B w a a c r k d Program Book San Diego, California • August 2-5, 2019 Mythcon 50: Moving Forward, Looking Back Guests of Honor Verlyn Flieger, Tolkien Scholar Tim Powers, Fantasy Author Conference Theme To give its far-flung membership a chance to meet, and to present papers orally with audience response, The Mythopoeic Society has been holding conferences since its early days. These began with a one-day Narnia Conference in 1969, and the first annual Mythopoeic Conference was held at the Claremont Colleges (near Los Angeles) in September, 1970. This year’s conference is the third in a series of golden anniversaries for the Society, celebrating our 50th Mythcon. Mythcon 50 Committee Lynn Maudlin – Chair Janet Brennan Croft – Papers Coordinator David Bratman – Programming Sue Dawe – Art Show Lisa Deutsch Harrigan – Treasurer Eleanor Farrell – Publications J’nae Spano – Dealers’ Room Marion VanLoo – Registration & Masquerade Josiah Riojas – Parking Runner & assistant to the Chair Venue Mythcon 50 will be at San Diego State University, with programming in the LEED Double Platinum Certified Conrad Prebys Aztec Student Union, and onsite housing in the South Campus Plaza, South Tower. Mythcon logo by Sue Dawe © 2019 Thanks to Carl Hostetter for the photo of Verlyn Flieger, and to bg Callahan, Paula DiSante, Sylvia Hunnewell, Lynn Maudlin, and many other members of the Mythopoeic Society for photos from past conferences. Printed by Windward Graphics, Phoenix, AZ 3 Verlyn Flieger Scholar Guest of Honor by David Bratman Verlyn Flieger and I became seriously acquainted when we sat across from each other at the ban- quet of the Tolkien Centenary Conference in 1992. -

Mythic Journeys Corporate Sponsors and Partners

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE: April 27, 2004 MEDIA CONTACTS: Anya Martin (678) 468-3867 Dawn Zarimba Edelman Public Relations (404) 262-3000 [email protected] Mythic Journeys Corporate Sponsors and Partners Corporate Sponsors The Krispy Kreme Foundation (http://www.krispykreme.com/) The Krispy Kreme Foundation was created to help people, individually and collectively, achieve their potential and enrich their lives. The foundation is guided by the belief that stories have the unique ability to reveal and illuminate the ways in which individuals, organizations, nations and cultures are part of an integrated and interdependent whole. The Krispy Kreme Foundation promotes stories and storytelling, which both support individual and collective efforts to choose a future that is resonate with the best in the human spirit. Borders’ Books & Music (http://www.bordersgroupinc.com ) With approximately 450 locations in the United States, Borders Books & Music stores can be found in all parts of the country. Borders Group also operates 36 Books etc. locations in the United Kingdom as well as 37 Borders superstores throughout the U.K., Australia, New Zealand, Singapore and the commonwealth of Puerto Rico. More than 32,000 Borders Books & Music employees worldwide help to provide our customers with the books, music, movies, and other entertainment items tailored specifically to the interests of the community they serve. We are a company committed to our people, to diversity, to our customers, and to our communities. PARABOLA Magazine (http://www.parabola.org/) PARABOLA is a quarterly journal and one of the pioneering publications on the subject of myth and tradition. Every issue explores one of the facets of human existence from the point of view of as many of the world's religious and spiritual traditions as possible, through the prism of story and symbol, myth, ritual and sacred teachings.