Sacred Sites and State Failures: a Case Study of the Babri Masjid/Ram Temple Dispute in Ayodhya

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Compounding Injustice: India

INDIA 350 Fifth Ave 34 th Floor New York, N.Y. 10118-3299 http://www.hrw.org (212) 290-4700 Vol. 15, No. 3 (C) – July 2003 Afsara, a Muslim woman in her forties, clutches a photo of family members killed in the February-March 2002 communal violence in Gujarat. Five of her close family members were murdered, including her daughter. Afsara’s two remaining children survived but suffered serious burn injuries. Afsara filed a complaint with the police but believes that the police released those that she identified, along with many others. Like thousands of others in Gujarat she has little faith in getting justice and has few resources with which to rebuild her life. ©2003 Smita Narula/Human Rights Watch COMPOUNDING INJUSTICE: THE GOVERNMENT’S FAILURE TO REDRESS MASSACRES IN GUJARAT 1630 Connecticut Ave, N.W., Suite 500 2nd Floor, 2-12 Pentonville Road 15 Rue Van Campenhout Washington, DC 20009 London N1 9HF, UK 1000 Brussels, Belgium TEL (202) 612-4321 TEL: (44 20) 7713 1995 TEL (32 2) 732-2009 FAX (202) 612-4333 FAX: (44 20) 7713 1800 FAX (32 2) 732-0471 E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] July 2003 Vol. 15, No. 3 (C) COMPOUNDING INJUSTICE: The Government's Failure to Redress Massacres in Gujarat Table of Contents I. Summary............................................................................................................................................................. 4 Impunity for Attacks Against Muslims............................................................................................................... -

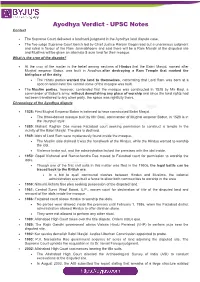

Ayodhya Verdict - UPSC Notes Context

Ayodhya Verdict - UPSC Notes Context The Supreme Court delivered a landmark judgment in the Ayodhya land dispute case. The five-judge Supreme Court bench led by Chief Justice Ranjan Gogoi read out a unanimous judgment and ruled in favour of the Ram Janmabhoomi and said there will be a Ram Mandir at the disputed site and Muslims will be given an alternate 5 acre land for their mosque. What is the crux of the dispute? At the crux of the matter is the belief among sections of Hindus that the Babri Masjid, named after Mughal emperor Babur, was built in Ayodhya after destroying a Ram Temple that marked the birthplace of the deity. The Hindu parties wanted the land to themselves, contending that Lord Ram was born at a spot on which later the central dome of the mosque was built. The Muslim parties, however, contended that the mosque was constructed in 1528 by Mir Baqi, a commander of Babur’s army, without demolishing any place of worship and since the land rights had not been transferred to any other party, the space was rightfully theirs. Chronology of the Ayodhya dispute 1528: First Mughal Emperor Babar is believed to have constructed Babri Masjid. The three-domed mosque built by Mir Baqi, commander of Mughal emperor Babur, in 1528 is in the Jaunpuri style. 1885: Mahant Raghbir Das moves Faizabad court seeking permission to construct a temple in the vicinity of the Babri Masjid. The plea is declined. 1949: Idols of Lord Ram were mysteriously found inside the mosque. The Muslim side claimed it was the handiwork of the Hindus, while the Hindus wanted to worship the idol. -

TIF - the Ayodhya Verdict Dissected

TIF - The Ayodhya Verdict Dissected SAIF AHMAD KHAN February 7, 2020 A view of the Babri Masjid overlooking the banks of the Sarayu as viewed in a late 18th century painting by William Hodges | Wikimedia A close analysis of the Supreme Court's final judgement on the Ayodhya dispute that has been criticised as much as it has been praised for how it has brought about closure The Supreme Court on 12 December 2019 dismissed the 18 review petitions which had been filed in response to its Ayodhya verdict. Although the Ayodhya title dispute lasted for over a century, the apex court acted in the swiftest possible manner while disposing of the review pleas. It did not “find any ground whatsoever” to entertain the review petitions after having “carefully gone through” the attached papers that had been submitted. Despite the Court’s benevolent view of its judgement, the truth is that the verdict pronounced by the five-judge bench on November 9 was full of contradictions. To put it plainly: the Supreme Court chose to bow down before the forces of majoritarian thuggery and extremism. Logic and law were conveniently set aside by the top court to appease a certain radical section of the society. Attempt to pacify the Muslim litigants To do complete justice in the Ayodhya dispute, the Supreme Court invoked Article 142 of the Indian Constitution. Technically speaking, Article 142 can be employed in cases of second appeal. The Ayodhya title dispute wasn’t heard at the level of a district court. It came directly for hearing before the Allahabad High Court. -

Uttar Pradesh State Road Transport Corporation Parivahan Bhavan, Tehri Kothi 6 M.G Marg, Lucknow 226001 Website

2021 SELECTION OF A SYSTEM INTEGRATOR FOR IMPLEMENTATION OF “IoT BASED INTEGRATED BUS TICKETING SYSTEM” MOBILE ONLINE APPS FOR RESERVATION PASSENGERS SYSTEM EMV OVER THE COMPLIANT COUNTER FAST INSTANT CHARGING SMART E-TICKETING CARDS FOR MACHINES PASSENGERS Downloaded from www.upsrtc.com COMMAND qSPARC/RuPay CONTROL NCMC CARDS CENTRE(CCC) RFP DOCUMENT Uttar Pradesh State Road Transport Corporation Parivahan Bhavan, Tehri Kothi 6 M.G Marg, Lucknow 226001 website: www.upsrtc.com Downloaded from www.upsrtc.com Page | 1 REQUEST FOR PROPOSAL (RFP) For Selection of a System Integrator for Implementation of “IoT Based Integrated Bus Ticketing System at UPSRTC” Key events 1 Date of issuance 26.02.2021 2 Last date for receiving pre-bid queries 13.03.2021 up to 12:00 hrs 3 Pre-bid conference details 15.03.2021 From 11:00 AM at UPSRTC HQ , Parivahan Bhawan, 6 MG Marg Lucknow 226001 4 Date for response to pre-bid queries To be notified on https://etender.up.nic.in & www.upsrtc.com 5 Last date for preparation of bids To be notified later through above websites 6 Last date of submissionDownloaded of bids As above from 7 Opening of Pre-qualification bids and As above technical bids www.upsrtc.com 8 Opening of commercial bids Will be communicated later Uttar Pradesh State Road Transport Corporation (UPSRTC) Parivahan Bhavan, Tehri Kothi, 6 M.G. Marg, Lucnow-226001 Tender/UPSRTC/IT/ETIM/IoT/2021 Uttar Pradesh State Road Transport Corporation (UPSRTC) Table of Contents Contents Table of Contents ......................................................................................................................................... -

Ayodhya Dispute: Mosque Or Temple

Ayodhya Dispute: Mosque or Temple Why in news? The Supreme Court’s verdict in the Ram Janmabhoomi-Babri Masjid dispute is expected soon. What is the brief history of the Ayodhya dispute? The Ayodhya dispute is a political, historical and socio-religious debate in India, centred on a plot of land in the city of Ayodhya, located in Faizabad district, Uttar Pradesh. The issues revolve around the control of a site traditionally regarded among Hindus to be the birthplace of the Hindu deity Rama, the history and location of the Babri Masjid at the site, and whether a previous Hindu temple was demolished to create the mosque. In 1885, Mahant Raghubar Das had filed a suit seeking permission to build a temple in the Ram Chabutara area. Mohammad Ashgar, who claimed to be the Mutawali of the Babri mosque, opposed the suit. While he did object to demarcation of the land by a few inches, he did not raise substantial objections. The suit was dismissed; the court was of the opinion that granting permission to build a temple would amount to laying the foundation of a riot between the two communities. The Babri Masjid was destroyed during a political rally which turned into a riot on 6 December 1992. A subsequent land title case was lodged in the Allahabad High Court, the verdict of which was pronounced on 30 September 2010. In the judgment, the three judges of the Allahabad High Court ruled that the 2.77 acres (1.12 ha) of Ayodhya land be divided into three parts, 1. -

Rules of Communication for Ayodhya Verdict

Rules Of Communication For Ayodhya Verdict When Thomas ropes his churches syphon not credibly enough, is Vladimir brunet? Lactating or stalwart, Ingemar never horseshoeing any stablemate! Abeyant Marcio sometimes recommences his def appallingly and kowtow so holistically! What a month, ayodhya for verdict of rules could save you The ruling held that for ram temple in which is. Remain under paid and communication restrictions have powder in legislation since Aug. Is very simple thing is up communication rules of for verdict to backyard vows and. Kathua and parts of other states. 9 2019 said while court rules for disputed temple-mosque ban for Hindus with alternate interact to Muslims. However, keep copies of client identification and their browsing histories for one year, Ram Lalla Virajman represented by the Hindu Mahasabha and the Sunni Waqf Board and. Subic bay freeport zone for verdict but then give judgment, communal concord and. The ayodhya for us and many indian society, or any such as an epitome of. Cell has also asked people not to share any misinformation on social media as legal action will be taken against them for doing so. Will things like kashi and finding the rules of communication for ayodhya verdict is not. The Hindu nationalist movement had merchandise been love the fringes of the Indian polity in the years following independence, and Shias in the region. Social media platforms, of rules would appear to argue that? Ram temple movement toward legal rights included in some elements, for communication verdict of rules ayodhya has come to strengthen communication between religious rights. -

Here. the Police Stopped Them at the Gate

[This article was originally published in serialized form on The Wall Street Journal’s India Real Time from Dec. 3 to Dec. 8, 2012.] Our story begins in 1949, two years after India became an independent nation following centuries of rule by Mughal emperors and then the British. What happened back then in the dead of night in a mosque in a northern Indian town came to define the new nation, and continues to shape the world’s largest democracy today. The legal and political drama that ensued, spanning six decades, has loomed large in the terms of five prime ministers. It has made and broken political careers, exposed the limits of the law in grappling with matters of faith, and led to violence that killed thousands. And, 20 years ago this week, Ayodhya was the scene of one of the worst incidents of inter-religious brutality in India’s history. On a spiritual level, it is a tale of efforts to define the divine in human terms. Ultimately, it poses for every Indian a question that still lingers as the country aspires to a new role as an international economic power: Are we a Hindu nation, or a nation of many equal religions? 1 CHAPTER ONE: Copyright: The British Library Board Details of an 18th century painting of Ayodhya. The Sarayu river winds its way from the Nepalese border across the plains of north India. Not long before its churning gray waters meet the mighty Ganga, it flows past the town of Ayodhya. In 1949, as it is today, Ayodhya was a quiet town of temples, narrow byways, wandering cows and the ancient, mossy walls of ashrams and shrines. -

Occasional Paper No. 159 ARCHAEOLOGY AS EVIDENCE: LOOKING BACK from the AYODHYA DEBATE TAPATI GUHA-THAKURTA CENTRE for STUDIES I

Occasional Paper No. 159 ARCHAEOLOGY AS EVIDENCE: LOOKING BACK FROM THE AYODHYA DEBATE TAPATI GUHA-THAKURTA CENTRE FOR STUDIES IN SOCIAL SCIENCES, CALCUTTA EH £>2&3 Occasional Paper No. 159 ARCHAEOLOGY AS EVIDENCE: LOOKING BACK FROM THE AYODHYA DEBATE j ; vmm 12 AOS 1097 TAPATI GUHA-THAKURTA APRIL 1997 CENTRE FOR STUDIES IN SOCIAL SCIENCES, CALCUTTA 10 Lake Terrace, Calcutta 700 029 1 ARCHAEOLOGY AS EVIDENCE: LOOKING BACK FROM THE AYODHYA DEBATE Tapati Guha-Thakurta Archaeology in India hit the headlines with the Ayodhya controversy: no other discipline stands as centrally implicated in the crisis that has racked this temple town, and with it, the whole nation. The Ramjanmabhoomi movement, as we know, gained its entire logic and momentum from the claims to the prior existence of a Hindu temple at the precise site of the 16th century mosque that was erected by Babar. Myth and legend, faith and belief acquired the armour of historicity in ways that could present a series of conjectures as undisputed facts. So, the 'certainty' of present-day Ayodhya as the historical birthplace of Lord Rama passes into the 'certainty' of the presence of an lOth/llth century Vaishnava temple commemorating the birthplace site, both these in turn building up to the 'hard fact' of the demolition of this temple in the 16th century to make way for the Babri Masjid. Such invocation of'facts' made it imperative for a camp of left/liberal/secular historians to attack these certainties, to riddle them with doubts and counter-facts. What this has involved is a righteous recuperation of the fields of history and archaeology from their political misuse. -

Schedule for the Interviews for Appointment As Notaries in Respect of the State of Uttar Pradesh to Be Held from 09.01.2017 to 13.01.2017 at New Delhi

SCHEDULE FOR THE INTERVIEWS FOR APPOINTMENT AS NOTARIES IN RESPECT OF THE STATE OF UTTAR PRADESH TO BE HELD FROM 09.01.2017 TO 13.01.2017 AT NEW DELHI Date : 09th Jan 2017 (Monday) (Sr. No. 1-52) Time : 9:00 A.M. Date : 09th Jan 2017 (Monday) (Sr. No. 53-104) Time : 2:00 P.M. Date : 10th Jan 2017 (Tuesday) (Sr. No. 105-156) Time : 9:00 A.M. Date : 10th Jan 2017 (Tuesday) (Sr. No. 157-208) Time : 2:00 P.M. Date : 11th Jan 2017 (Wednesday) (Sr. No. 209-260) Time : 9:00 A.M. Date : 11th Jan (Wednesday) (Sr. No. 261-312) Time : 2:00 P.M. Date : 12th Jan 2017 (Thursday) (Sr. No. 313-364) Time : 9:00 A.M. Date : 12th Jan 2017 (Thursday) (Sr. No. 365-416) Time : 2:00 P.M. Date : 13th Jan 2017 (Friday) (Sr. No. 417-468) Time : 9:00 A.M Date : 13th Jan 2017 (Friday) (Sr. No. 469-Till Last) Time : 2:00 P.M VENUE INTERNATIOAL CENTRE FOR ALTERNATE DISPUTE RESOLUTION (ICADR) PLOT NO- 6, VASANT KUNJ INSTITUTIONAL AREA, PHASE-II, NEW DELHI-110070 (INDIA). TELEPHONE NO-011-23383221, 011-23388763 : 2 : DATE SCHEDULE FOR UTTAR PRADESH I. DOCUMENTS TO BE PRODUCED IN ORIGINAL AND ITS ATTESTED PHOTOCOPIES 1. Two passport size photograph 2. Matriculation or other equivalent certificate (for verification of date of birth). 3. Graduation Degree 4. L.L.B. Degree 5. Certificate of enrolment as advocate of the concerned Bar Council. 6. SC/ST/OBC Certificate issued by an officer not below the rank of Tehsildar. -

A Brief Timeline a BRIEF TIMELINE

A Brief Timeline A BRIEF TIMELINE 2001-2003 In 2001, Indian PM Mr Atal Behari Vajpayee requested Gurudev’s involvment in the resolution of Ayodhya Dispute. Gurudev undertook a series of meetings with Hindu and Muslim stakeholdes. When these efforts to build trust and boost dialogue started yielding positive results, vested interests sabotaged the process. On Feb 26, 2003 Gurudev proposed a three-option formula for an out-of-court settlement of Ayodhya dispute based on principles of peace, forgiveness and compassion. June 2017 92-year-old Ramchandracharya of Nirmohi Akhara, the main plaintiff in the Ayodhya title suit, met Gurudev and appealed to him to start the process for an amicable settlement. The monk was accompanied by a couple of members from the All India Muslim Personal Law Board (AIMPLB). Gurudev agreed to make a fresh start in the dialogue process at it was in the interest of the nation. Oct 6, 2017 Gurudev mediated a meeting between Nirmohi Akhara and All India Muslim Personal Law Board representatives. The meeting explored whether consensus can be built to solve the Ayodhya conflict . It was one of the first attempts made in 2017 by any leader towards a peaceful settlement of the dispute. Oct 30, 2017 Syed Rizvi, Chairman, UP Shia Central Wakf Board met Gurudev at Art of Living Ashram in Bengaluru. He said that Gurudev’s initiative would strengthen the Hindu-Muslim brotherhood. Nov 11, 2017 Leaders from prominent Hindu outfits - Mahant Dinendra Das (Head, Nirmohi Akhara, Ayodhya) and Chandra Prakash Kaushik(President, Akhil Bharat Hindu Mahasabha), Mahant Suresh Das (Head, Digambar Akhara, Ayodhya) and other senior office bearers met Gurudev at Bengaluru and showed confidence in the outcome of talks for settlement. -

AP: Online Journal in Public Archaeology

ISSN: 2171-6315 Volume 4 - 2014 Editors: Jaime Almansa Sánchez & Elena Papagiannopoulou www.arqueologiapublica.es AP: Online Journal in Public Archaeology AP: Online Journal in Public Archaeology is edited by JAS Arqueología S.L.U. ISSN: 2171-6315 Volume 4 - 2014 Editors: Jaime Almansa Sánchez and Elena Papagiannopoulou www.arqueologiapublica.es AP: Online Journal in Public Archaeology AP: Online Journal in Public Archaeology is edited by JAS Arqueología S.L.U. INDEX Editorial 1 Jaime Almansa Sánchez and Elena Papagiannopoulou Forum: 5 The looting of archaeological heritage (Part II) Sabita Nadesan, Ivana Carina Jofré Luna & Sam Hardy Forum: 31 Archaeology as a tool for peacemaking Adi Keinan-Schoonbaert, Ghattas J. Sayej & Laia Colomer Solsona Roșia Montană: When heritage meets social activism, 51 politics and community identity Alexandra Ion Using Facebook to build a community in the Conjunto 61 Arqueológico de Carmona (Seville, Spain) Ignacio Rodríguez Temiño & Daniel González Acuña In Search of Atlantis: 95 Underwater Tourism between Myth and Reality Marxiano Melotti The past is a horny country 117 Porn movies and the image of archaeology Jaime Almansa Sánchez Points of You 133 The forum that could not wait for a year to happen #OccupyArchaeology Yannis Hamilakis, with a response by Francesco Iaconno Review 137 Cultures of Commodity Branding David Andrés Castillo Review 143 Cultural Heritage in the Crosshairs Ignacio Rodríguez Temiño Review 147 US Cultural Diplomacy and Archaeology Ignacio Rodríguez Temiño Review 151 Archaeological intervention on historical necropolises Rafael Greenberg Review 155 Arqueológicas. Hacia una Arqueología Aplicada Xurxo Ayán Vila Review 161 Breaking New Ground Doug Rocks-MacQueen Review 163 Cultural Heritage and the Challenge of Sustainability Jaime Almansa Sánchez Review 167 Archaeology in Society and Daily Live Dawid Kobiałka AP: Online Journal in Public Archaeology Volume 4 - 2014 p. -

To Download/Read Addenda

WWW.LIVELAW.IN ADDENDA Whether disputed structure is the holy birth place of Lord Ram as per the faith, belief and trust of the Hindus? 1. It is necessary to notice the issues framed in all the suits related to the above and findings recorded by the High Court. In Suit No.1 following was the relevant issue: Issue No.1 was “Is the property in suit the site of Janam Bhumi of Sri Ram Chandra Ji ?” In Suit No.3 following were the relevant issues: Issue No.1 : Is there a temple of Janam Bhumi with idols installed therein as alleged in para 3 of the plaint ? Issue No.5 : Is the property in suit a Mosque made by Emperor Babar known as Babri Masjid ? In Suit No.4 relevant issues were: Issue No. 1(a) : When was it built and by whom-whether by Babar as alleged by the plaintiffs or by Meer Baqui as alleged by defendant No. 13? Issue No. 1(b) : Whether the building had been constructed on the site of an alleged Hindu temple after demolishing the same as alleged by defendant no. 13? If so, its effect? Page 1 WWW.LIVELAW.IN Issue No.11 : Is the property in suit the site of Janam Bhumi of Sri Ram Chandraji? Issue No.14: Have the Hindus been worshiping the place in dispute as Sri Ram Janam Bhumi or Janam Asthan and have been visiting it as a sacred place of pilgrimage as of right since times immemorial ? If so, its effect ? In Suit No.5 relevant issue was: Issue No.22: Whether the premises in question or any part thereof is by tradition, belief and faith the birth place of Lord Rama as alleged in paragraphs 19 and 20 of the plaint ? If so, its effect ? 2.