Kansas Elections: Then and Now

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Honorary Degree Recipients and Degrees Conferred Honoris Causa

HONORARY DEGREE RECIPIENTS AND DEGREES CONFERRED HONORIS CAUSA 1888 Rev. Francis T. Ingalls D.D. Judge David J. Brewer LL.D. 1891 Solon O. Thacher LL.D. 1892 Rev. James G. Dougherty D.D. Rev. Linus Blakesley D.D. 1902 Francis L. Hayes D.D. John C. McClintock LL.D. John W. Scroggs D.D. Harrison Hannahs Hon. M.A. 1904 William O. Johnston LL.D. William H. Rossington LL.D. 1905 Archibald McCullough LL.D. Henry E. Thayer D.D. Luther Denny Wittemore D.Litt. 1908 L.C. Schnacke D.D. C.H. Small D.D. 1910 Calvin Blodgett Moody D.D. John B. Silcox D.D. 1911 Henry Frederick Cope D.D. 1912 James E. Adams D.D. Hiram Blake Harrison D.D. 1913 William Francis Bowen M. of Chirurgery 1914 Jacob C. Mohler LL.D. 1915 Milton Smith Littlefield D.D. Harry Olson LL.D. Frank Knight Sanders LL.D. 1916 Duncan Lendrum McEachron LL.D. 1917 Noble S. Elderkin D.D. Morris H. Turk D.D. Harry B. Wilson LL.D. 1918 James Wise D. Litt. 1919 William Asbury Harshbarger D. Sci. Margaret Hill McCarter D. Litt. Henry F. Mason D. Litt. 1921 Henry J. Allen LL.D. Edward G. Buckland LL.D. Rev. 5/12/12 1922 Ozora S. Davis LL.D. Frank M. Sheldon D.D. 1923 Harwod O. Benton Hon. A.M. Angelus T. Burch Hon. A.M. Arthur S. Champeny Hon. A.M. Arthur E. Hertzler LL.D. 1925 Charles Curtis LL.D. Oscar A. Kropf LL.D. Richard E. Kropf LL.D. -

Congressional Record United States Th of America PROCEEDINGS and DEBATES of the 112 CONGRESS, FIRST SESSION

E PL UR UM IB N U U S Congressional Record United States th of America PROCEEDINGS AND DEBATES OF THE 112 CONGRESS, FIRST SESSION Vol. 157 WASHINGTON, THURSDAY, SEPTEMBER 8, 2011 No. 132 Senate The Senate met at 9:30 a.m. and was from the State of New Mexico, to perform MEASURE PLACED ON THE called to order by the Honorable TOM the duties of the Chair. CALENDAR—S.J. RES 26 UDALL, a Senator from the State of DANIEL K. INOUYE, President pro tempore. Mr. REID. Mr. President, I am told New Mexico. that S.J. Res. 26 is due for a second Mr. UDALL of New Mexico thereupon reading. PRAYER assumed the chair as Acting President The ACTING PRESIDENT pro tem- pro tempore. The Chaplain, Dr. Barry C. Black, of- pore. The clerk will report the joint fered the following prayer: resolution by title for the second time. Let us pray. f The assistant legislative read as fol- Lord God, through whom we find lib- lows: erty and peace, lead us in Your right- RECOGNITION OF THE MAJORITY A joint resolution (S.J. Res. 26) expressing eousness and make the way straight LEADER the sense of Congress that Secretary of the before our lawmakers. As they grapple The ACTING PRESIDENT pro tem- Treasury Timothy Geithner no longer holds with complex issues and feel the need pore. The majority leader is recog- the confidence of Congress or of the people of for guidance, lead them to the deci- nized. the United States. sions that will best glorify You. -

Kathleen Sebelius, Governor of Kansas, 2003-2009

Kathleen Sebelius, governor of Kansas, 2003-2009. Kansas History: A Journal of the Central Plains 40 (Winter 2017–2018): 262-289 262 Kansas History “Find a Way to Find Common Ground”: A Conversation with Former Governor Kathleen Sebelius edited by Bob Beatty and Linsey Moddelmog athleen Mary (Gilligan) Sebelius, born May 15, 1948, in Cincinnati, Ohio, served as the State of Kansas’s forty-fourth chief executive from January 13, 2003, to April 28, 2009, when she resigned to serve in President Barack Obama’s cabinet as secretary for the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). Sebelius rose to the governorship after serving in the Kansas House of Representatives from 1987 to 1995 and serving two terms as Kansas insurance commissioner from 1995 to 2003. She was the first insurance commissioner from the Democratic Party in Kansas history, defeating Republican Kincumbent Ron Todd in 1994, 58.6 percent to 41.4 percent. She ran for reelection in 1998 and easily defeated Republican challenger Bryan Riley, 59.9 to 40.1 percent. In the 2002 gubernatorial race, Sebelius defeated Republican state treasurer Tim Shallenburger, 52.9 to 45.1 percent. She won reelection in 2006 by a vote of 57.9 to 40.4 percent against her Republican challenger, state senator Jim Barnett.1 Sebelius never lost an election to public office in Kansas.2 Sebelius’s 2002 gubernatorial victory marked the first and only father-daughter pair to serve as governors in the United States. Her father, John Gilligan, was Democratic governor of Ohio from 1971 to 1975. Sebelius’s gubernatorial leadership style was one of bipartisanship, as her Democratic Party was always in the minority in the state legislature. -

![CHAIRMEN of SENATE STANDING COMMITTEES [Table 5-3] 1789–Present](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8733/chairmen-of-senate-standing-committees-table-5-3-1789-present-978733.webp)

CHAIRMEN of SENATE STANDING COMMITTEES [Table 5-3] 1789–Present

CHAIRMEN OF SENATE STANDING COMMITTEES [Table 5-3] 1789–present INTRODUCTION The following is a list of chairmen of all standing Senate committees, as well as the chairmen of select and joint committees that were precursors to Senate committees. (Other special and select committees of the twentieth century appear in Table 5-4.) Current standing committees are highlighted in yellow. The names of chairmen were taken from the Congressional Directory from 1816–1991. Four standing committees were founded before 1816. They were the Joint Committee on ENROLLED BILLS (established 1789), the joint Committee on the LIBRARY (established 1806), the Committee to AUDIT AND CONTROL THE CONTINGENT EXPENSES OF THE SENATE (established 1807), and the Committee on ENGROSSED BILLS (established 1810). The names of the chairmen of these committees for the years before 1816 were taken from the Annals of Congress. This list also enumerates the dates of establishment and termination of each committee. These dates were taken from Walter Stubbs, Congressional Committees, 1789–1982: A Checklist (Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1985). There were eleven committees for which the dates of existence listed in Congressional Committees, 1789–1982 did not match the dates the committees were listed in the Congressional Directory. The committees are: ENGROSSED BILLS, ENROLLED BILLS, EXAMINE THE SEVERAL BRANCHES OF THE CIVIL SERVICE, Joint Committee on the LIBRARY OF CONGRESS, LIBRARY, PENSIONS, PUBLIC BUILDINGS AND GROUNDS, RETRENCHMENT, REVOLUTIONARY CLAIMS, ROADS AND CANALS, and the Select Committee to Revise the RULES of the Senate. For these committees, the dates are listed according to Congressional Committees, 1789– 1982, with a note next to the dates detailing the discrepancy. -

National Governors' Association Annual Meeting 1977

Proceedings OF THE NATIONAL GOVERNORS' ASSOCIATION ANNUAL MEETING 1977 SIXTY-NINTH ANNUAL MEETING Detroit. Michigan September 7-9, 1977 National Governors' Association Hall of the States 444 North Capitol Street Washington. D.C. 20001 Price: $10.00 Library of Congress Catalog Card No. 12-29056 ©1978 by the National Governors' Association, Washington, D.C. Permission to quote from or to reproduce materials in this publication is granted when due acknowledgment is made. Printed in the United Stales of America CONTENTS Executive Committee Rosters v Standing Committee Rosters vii Attendance ' ix Guest Speakers x Program xi OPENING PLENARY SESSION Welcoming Remarks, Governor William G. Milliken and Mayor Coleman Young ' I National Welfare Reform: President Carter's Proposals 5 The State Role in Economic Growth and Development 18 The Report of the Committee on New Directions 35 SECOND PLENARY SESSION Greetings, Dr. Bernhard Vogel 41 Remarks, Ambassador to Mexico Patrick J. Lucey 44 Potential Fuel Shortages in the Coming Winter: Proposals for Action 45 State and Federal Disaster Assistance: Proposals for an Improved System 52 State-Federal Initiatives for Community Revitalization 55 CLOSING PLENARY SESSION Overcoming Roadblocks to Federal Aid Administration: President Carter's Proposals 63 Reports of the Standing Committees and Voting on Proposed Policy Positions 69 Criminal Justice and Public Protection 69 Transportation, Commerce, and Technology 71 Natural Resources and Environmental Management 82 Human Resources 84 Executive Management and Fiscal Affairs 92 Community and Economic Development 98 Salute to Governors Leaving Office 99 Report of the Nominating Committee 100 Election of the New Chairman and Executive Committee 100 Remarks by the New Chairman 100 Adjournment 100 iii APPENDIXES I Roster of Governors 102 II. -

Bill Graves Kansas History Govenor Profile.Pdf

*RYHUQRU:LOOLDP3UHVWRQ*UDYHVLQWKHJRYHUQRU·VRIÀFHLQWKHV Kansas History: A Journal of the Central Plains 36 (Autumn 2013): 172–97 172 Kansas History “Doing What Needed to Get Done, When It Needed to Get Done”: A Conversation with Former Governor Bill Graves edited by Bob Beatty and Virgil W. Dean LOOLDP3UHVWRQ´%LOOµ*UDYHVERUQLQ6DOLQD.DQVDVRQ-DQXDU\VHUYHGDVWKHVWDWH·VIRUW\WKLUG FKLHIH[HFXWLYHIURP-DQXDU\WR-DQXDU\*UDYHVHQMR\HGLPSUHVVLYHHOHFWRUDOVXFFHVV winning all four of his statewide elections, and he can make a strong claim as Kansas’s most popular JRYHUQRUDVKHZRQUHHOHFWLRQLQZLWKDVWDJJHULQJSHUFHQWRIWKHYRWHWKHKLJKHVWSHUFHQWDJHLQ Wstate history. 1*UDYHVVWDUWHGKLVSDWKWRWKHJRYHUQRUVKLSLQIURPDQXQXVXDOSO DFHWKHRIÀFHRIWKH.DQVDVVHFUHWDU\ RIVWDWHZRUNLQJIRUWKHQVHFUHWDU\-DFN%ULHU:KHQ%ULHUOHIWWKHMRELQWRUXQIRUJRYHUQRU*UDYHVUDQDQGZRQWKH UDFHWREHWKHVWDWH·VFKLHIHOHFWLRQRIÀFHUGHIHDWLQJ6WDWH5HSUHVHQWDWLYH-XGLWK&´-XG\µ5XQQHOVD7RSHND'HPRFUDW WRSHUFHQW+HUDQIRUUHHOHFWLRQLQDQGHDVLO\GHIHDWHG'HPRFUDWLFFKDOOHQJHU5RQDOG-'LFNHQV ,Q*UDYHV SUHYDLOHGLQDFURZGHG5HSXEOLFDQJXEHUQDWRULDOSULPDU\JDUQHULQJSHUFHQWRIWKHYRWHYHUVXVSHUFHQWIRUEXVLQHVVPDQ *HQH%LFNQHOODQGSHUFHQWIRU6WDWH6HQDWRU)UHG.HUUKLVWZRVWURQJHVWRSSRQHQWV,QWKHJHQHUDOHOHFWLRQFRQWHVWWKDW \HDU*UDYHVGHIHDWHG'HPRFUDWLF&RQJUHVVPDQ-LP6ODWWHU\WRSHUFHQWDQGEHFDPHWKHÀUVWVHFUHWDU\RIVWDWHLQ Bob Beatty is a professor of political science at Washburn University and a political analyst and consultant for KSNT and KTKA television in Topeka. +HKROGVD3K'IURP$UL]RQD6WDWH8QLYHUVLW\DQGKLVLQWHUHVWVUHVHDUFKDQGSURMHFWVLQ.DQVDVIRFXVRQKLVWRU\DQGSROLWLFV+LVFRDXWKRUHGDUWLFOH -

2018 Butler County Commission.Pdf

The Kanas Governor’s One Shot Turkey Hunt has always considered our partnership with Butler County among out highest achievements. Our success is your success. We spotlight Butler County every year in the quest for the wild turkey gobbler. 29 of the last 31 years, the sitting Kansas Governor has participated in our hunt and all have harvested a bird. Many Governors of others states have participated in our event and our model is used when other states have developed their own event. No matter where our hunters hunt, they enter and exit through Butler County. The numbers in 2017 tell this story: 96 of 176 landowners and 44 of 80 current guides list a Butler County address. The volunteer workforce is a 4 to 1 ratio of folks that live in Butler County. We rented 92 hotel rooms. Many of the small town restaurants, antique and specialty shops are destinations that our hunters and guides visit each year. History of the event: Kansas Governor’s One Shot Turkey Hunt was established in 1986, the brainchild of El Dorado Chamber of Commerce President Marv McCown and then Kansas Governor Mike Hayden. Guest celebrities were invited to participate in the first invitation only hunt in 1987. Governors Hayden, Joan Finney, Bill Graves, Kathleen Sebelius, Mark Parkinson and current Governor Sam Brownback have all participated in this event. It began as an economic development tool, bringing business and industry executives to the area as well as people involved in outdoor resources/media. In the past 30 years, the Kansas Governor’s One Shot Turkey Hunt has evolved. -

Rocky Ford Renaissance Page 10 Commentary

Rural COOPERATIVESCOOPERATIVESUSDA / Rural Development January/February 2013 Rocky Ford Renaissance Page 10 Commentary Raising the bar on safety By William J. Nelson and DuPont, as described in the article, “Creating a safety Vice President, Corporate Citizenship and culture,” on page four of this issue. President, CHS Foundation North American agricultural co-ops and others in the farm Chair, ASHCA Board of Directors industry have a unique opportunity to step up to help ensure the safety of the agricultural workforce through public griculture, with its decentralized nature and communications, education and training. A diverse structure, lags other industries in We are particularly excited about the “2013 North reducing the toll on its workers. Its fatality American Agricultural Safety Summit” Sept. 25-27, 2013, at rate is eight times that of the all-industry the Marriott Minneapolis City Center Hotel. The Summit, average. In a typical year, about 500 workers hosted by ASHCA with support from CHS and others, has die while doing farm work in the the potential to galvanize the United States, and about 88,000 public and private sector in suffer lost-time injuries, forming a common vision on how according to the National to update national agricultural Institute for Occupational Safety safety and health priorities. and Health. The annual cost of Committed speakers include these injuries exceeds $4 billion. Carl Casale, president and CEO of If our agriculture industry is CHS, as well as John Howard, going to feed the world director of the National Institute population, which is estimated to for Occupational Safety and reach 9 billion by 2050, we must Health. -

1981 NGA Annual Meeting

PROCEEDINGS OF THE NATIONAL GOVERNORS' ASSOCIATION ANNUAL MEETING 1981 SEVENTY-THIRD ANNUAL MEETING Atlantic City, New Jersey August 9-11, 1981 National Governors' Association Hall of the States 444 North Capitol Street Washington, D.C. 20001 These proceedings were recorded by Mastroianni and Formaroli, Inc. Price: $8.50 Library of Congress Catalog Card No. 12-29056 © 1982 by the National Governors' Association, Washington, D.C. Permission to quote from or reproduce materials in this publication is granted when due acknowledgment is made. Printed in the United States of America ii CONTENTS Executive Committee Rosters v Standing Committee Rosters vi Attendance x Guest Speaker xi Program xii PLENARY SESSION Welcoming Remarks Presentation of NGA Awards for Distinguished Service to State Government 1 Reports of the Standing Committees and Voting on Proposed Policy 5 Positions Criminal Justice and Public Protection 5 Human Resources 6 Energy and Environment 15 Community and Economic Development 17 Restoring Balance to the Federal System: Next Stepon the Governors' Agenda 19 Remarks of Vice President George Bush 24 Report of the Executive Committee and Voting on Proposed Policy Position 30 Salute to Governors Completing Their Terms of Office 34 Report of the Nominating Committee 36 Remarks of the New Chairman 36 Adjournment 39 iii APPENDIXES I. Roster of Governors 42 II. Articles of Organization 44 ill. Rules of Procedure 51 IV. Financial Report 55 V. Annual Meetings of the National Governors' Association 58 VI. Chairmen of the National Governors' Association, 1908-1980 60 iv EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE, 1981* George Busbee, Governor of Georgia, Chairman Richard D. Lamm, Governor of Colorado John V. -

1964 NGA Annual Meeting

Proceedings OF THE GOVERNORS' CONFERENCE 1964 Proceedings OF THE GOVERNORS' CONFERENCE 1964 FIFTY-SIXTH ANNUAL MEETING SHERATON -CLEVELAND HOTEL CLEVELAND, OHIO June 6-10, 1964 THE GOVERNORS' CONFERENCE 1313 EAST SIXTIETH STREET CHICAGO, ILLINOIS 60637 Puhlished hy THE GOVERNORS' CONFERENCE 1313 EAST SIXTIETH STREET CHICAGO, ILLINOIS 60637 CONTENTS Executive Committee . ix Other Committees of the Governors' Conference x Attendance xiii Guests .. xiv Program . xv Morning Session-Monday, June 8 Opening Session-Governor John Anderson, Jr., Presiding. 1 Invocation-The Most Reverend Clarence E. Elwell. 1 Address of Welcome-Governor James A. Rhodes . 1 Address by Chairman of the Governors' Conference- Governor John Anderson, Jr. 5 Adoption of Rules of Procedure 12 Report of Interim Study Committee on Federal Aid to Ed- ucation-Governor Terry Sanford . 19 Report of Committee on Federal-State Relations-Gover- nor Robert E. Smylie . 22 Afternoon Session-Monday, June 8 General Session-Governor John B. Connally, Presiding. 24 Federal-State Relations-The States and Congress Remarks-Senator Ernest Gruening. 27 Remarks-Senator Frank Carlson. 29 Remarks-Senator J. Caleb Boggs. 31 Remarks-Senator Frank J. Lausche 33 Remarks-Senator J. Howard Edmondson. 35 Remarks-Senator Len B. Jordan. 36 Remarks-Senator Milward L. Simpson 37 Discussion by all Governors . 39 Evening Session-Monday, June 8 Address-The Honorable Dwight D. Eisenhower .. 49 Morning Session-Tuesday, June 9 Plenary Session-Governor John Anderson, Jr., Presiding. 57 Invocation-The Reverend Lewis Raymond. 57 v Civil Rights Report of Panel on Education-Governor Richard J. Hughes. 62 Report of Panel on Employment-Governor Matthew E. Welsh . 64 Report of Panel on Public Accornrnodations-Governor John A. -

1D/ ''7: / I R/ C-4

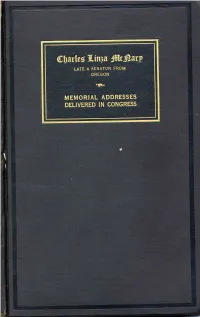

/ I /9 1d/ ''7: / c-4 I r/ Uemoriat'ethittS HELD IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES AND SENATE OF THE UNITED STATES. TOGETHER WITH REMARKS PRESENTED IN EULOGY OF QCiarte 3LinaJ*1tiitp LATE A SENATOR FROM OREGON cI3entp-eibtb Conve econb'eion UNITED STATEE GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE WASHINGTON 1946 PREPARED UNDER THE DIRECTION OF THE JOINT COMMITIEE ON PRINTING [2] Q1ontent Page Biography 5 Memorial services in the House: Memorial service program 11 Prayer by Rev. James Shera Montgomery 13 Roll of deceased Members, read by Mr. Alney E. Chaee, reading clerk of the House 15 Address by Mr. Jerry Voorhis, of California.. 18 Address by Mr. Karl E. Muudt, of South Dakota 25 Benediction by the Chaplain 34 Memorial addresses in the House: Mr. Homer D. Angell, of Oregon 37 Mr. William P. Elmer, of Missouri 39 Mr. William Lemke, of North Dakota 40 Memorial exercises in the Senate: Prayer by Rev. Frederick Brown Harris 43 Address by Mr. Arthur H. Vandenberg, of Michigan 45 Address by Mr. Rufus C. Rolman, of Oregon 48 Address by Mr. Wallace H. White, of Maine 51 Address by Mr. Alben W. Barkley, of Kentucky 53 Address by Mr. Kenneth MeKellar, of Tennessee 56 Address by Mr. John A. Danaher, of Connecticut 59 Address by Mr. Tom Connally, of Texas 62 Address by Mr. James J. Davis, of Pennsylvania 63 Address by Mr. Arthur Capper, of Kansas 66 Address by Mr. John H. Bankhead, of Alabama 69 Address by Mr. Richard B. Russell, of Georgia 72 Address by Mr. Homer T. Bone, of Washington 74 Address by Mr. -

Topeka Correctional Facility

If you have issues viewing or accessing this file contact us at NCJRS.gov. I :1 ,I I 'I I I ,I I I DOC I I I I KANSAS DEPARTMENT OF CORRECTIONS I November 1990 I Joan Finney Steven J .. Davies, Ph.D. Governor Secretary of Corrections 'I :1 I ;~ 138670 U.S. Department of Justice I National Institute of Justice This document has been reproduced exactly as received from the person or organization originating It. Points of view or opinions stated In this document are those of the authors and do not necessarily repr"sent I the oHiclal position or policies of the National Institute of Justice. Permission to reproduce this copyrighted material has been granted by Kansas Department of Corrections to the National Criminal Justice Aefereno':! Service (NCJAS). Further reproduction outside of the NCJAS system requires permlssfon I of the copyright owner. I Kansas Corrections Review I 'I ~I DOC I, I Kansas Department of Corrections Steven J. Davies, Ph.D., Secretary January 1991 I I I I I The Honorable Joan Finney Governor of Kansas I I I I I I I I Steven J. Davies, Ph.D. I Secretary of Corrections I I I I II I ,1 STATE OF KANSAS I I DEPAH.TNIENT OF COimECTIONS OFFICE OF THE SECRETARY Landoll State Office Building I ,900 S,W. jackson-Suite 400-N Joan Finney Topeka, Kansas 66612-1284 Steven J. Duvies, Ph.D. I GOGernor (913) 296-3317 Secretary January 1991 Fellow Kansans: I I I am pleased to present to you the first edition of the Kansas Corrections Review.