THE PROBLEM of TIME in LIGHT in AUGUST by Carolyn Porter Light in August Opens with Lena Grove Sitting in a Ditch Waiting for Armstid's Wagon to Reach Her

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Weekly Arts and Entertainment Supplement to the Daily Nexus Ous

The Weekly Arts and Entertainment Supplement to the Daily Nexus a t j o e (a k a FJ: It’s definitely with me, Raekwon, who want the real. Peo less and wild. Runnin’ (laughs) Lord Finesse, Joey Crack and more lyrical. It’s more Ghost Face, Nas, AZ ple who can look at Fat around spending mo featuring O .C . a n d F Fat Joe Da creative. It’s much and Mobb Deep. That Joe in the video and tell ney, having fun, cause KRS-One. That shit is Gangsta) is quickly be- tighter. You can hear will be the cream tour. that he really went even then he was still hot. Whoa! Boom Bam! coming a regular the whole thing and not AW: What do you through what he is say number one. I just loved I got the slammin’ tape, amongst New York’s have to fast-forward think of live hip-hop ing. I like the worst peo him. He represented me B. Niggas can’t fuck most elite emcees. Fat through songs. That’s shows? ple. I like the baddest and represented the with my tape right now. Joe’s new album, Jeal the problem with a lot FJ: There are certain people to enjoy my Bronx. I remember go Maybe I should take ous One’s Envy, is an of rappers today, they people who get busy. music. I want every ing to junior high you to the old school for impeccably produced, just think that they are Hip-hop shows have body to enjoy my music, school and everybody the last joint I’d play lyrically solid album, going to have three vid definitely gotten less but definitely the scum, was like “KRS! KRS!” I “The Vapors” by Biz with guest spots by eos — let’s make three creative in these stages the lowlifes. -

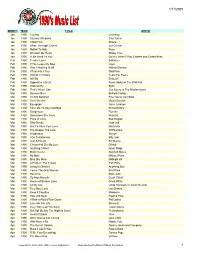

1990S Playlist

1/11/2005 MONTH YEAR TITLE ARTIST Jan 1990 Too Hot Loverboy Jan 1990 Steamy Windows Tina Turner Jan 1990 I Want You Shana Jan 1990 When The Night Comes Joe Cocker Jan 1990 Nothin' To Hide Poco Jan 1990 Kickstart My Heart Motley Crue Jan 1990 I'll Be Good To You Quincy Jones f/ Ray Charles and Chaka Khan Feb 1990 Tender Lover Babyface Feb 1990 If You Leave Me Now Jaya Feb 1990 Was It Nothing At All Michael Damian Feb 1990 I Remember You Skid Row Feb 1990 Woman In Chains Tears For Fears Feb 1990 All Nite Entouch Feb 1990 Opposites Attract Paula Abdul w/ The Wild Pair Feb 1990 Walk On By Sybil Feb 1990 That's What I Like Jive Bunny & The Mastermixers Mar 1990 Summer Rain Belinda Carlisle Mar 1990 I'm Not Satisfied Fine Young Cannibals Mar 1990 Here We Are Gloria Estefan Mar 1990 Escapade Janet Jackson Mar 1990 Too Late To Say Goodbye Richard Marx Mar 1990 Dangerous Roxette Mar 1990 Sometimes She Cries Warrant Mar 1990 Price of Love Bad English Mar 1990 Dirty Deeds Joan Jett Mar 1990 Got To Have Your Love Mantronix Mar 1990 The Deeper The Love Whitesnake Mar 1990 Imagination Xymox Mar 1990 I Go To Extremes Billy Joel Mar 1990 Just A Friend Biz Markie Mar 1990 C'mon And Get My Love D-Mob Mar 1990 Anything I Want Kevin Paige Mar 1990 Black Velvet Alannah Myles Mar 1990 No Myth Michael Penn Mar 1990 Blue Sky Mine Midnight Oil Mar 1990 A Face In The Crowd Tom Petty Mar 1990 Living In Oblivion Anything Box Mar 1990 You're The Only Woman Brat Pack Mar 1990 Sacrifice Elton John Mar 1990 Fly High Michelle Enuff Z'Nuff Mar 1990 House of Broken Love Great White Mar 1990 All My Life Linda Ronstadt (f/ Aaron Neville) Mar 1990 True Blue Love Lou Gramm Mar 1990 Keep It Together Madonna Mar 1990 Hide and Seek Pajama Party Mar 1990 I Wish It Would Rain Down Phil Collins Mar 1990 Love Me For Life Stevie B. -

Fat Joe Hard Not 2 Kill Free Mp3 Download Hard Not to Kill Lyrics

fat joe hard not 2 kill free mp3 download Hard Not To Kill Lyrics. [2nd Verse] Been in the game for the minute I'm making moves I switch careers I make them movies Got TV shows that's reppin' the Bronx I'm spitting Spanish I'm Viva Reggetone, niggaz Oh yeah I'm ready for war Any body hard body Just my four four I mean Cracks that niggaz I'll smack that Nigga I'll yap that Nigga Gun clap that Nigga Oh yeah I spit that shit Motivate young bucks how to flip them bricks Showed you how to jump off and switch the fifth And this all the mo'f*cking thanks I get Shit, I'm just being polite I'm married to this rap shit but the streets my life Matter of fact I. Fat joe hard not 2 kill free mp3 download. Fat Joe hails from the Bronx of New York. Fat Joe experienced the gritty life of the streets before parlaying his interests into a successful rap career and signing with Relativity Records and eventually Atlantic Records. Fat Joe released Represent . Fat Joe topped the Billboard Hot Rap Singles chart for a week with "Flow Joe." Fat Joe hit the Top 40 with help from R. Kelly with " We Thuggin' ." Jealous Ones Still Envy (Jose) was certified gold. Fat Joe hit the Top 40 with Ashanti with " What's Luv? " Fat Joe hit the Top 10 with " What's Luv? " Fat Joe topped the Billboard Top 40 Tracks chart for 2 weeks with " What's Luv? " Jealous Ones Still Envy (Jose) was certified platinum. -

Baruch College Library

~~~ ~_._..- ---=..... _.... '--.'-"'7"'~.''''~,~-,,,-~''' .'-' .~.- ......-.'.:-- ........~.,~ ..... _ ...~-..... : ,....._........... - BARUCH COLLEGE LIBRARY B~~RlJCH------PERlODIC.:-\L~ DE~K 3rd Floor ~ (NON-CIRCl!L~:\TING) Vol.. 71':, .Num.ber5 Informatton Now' October 29,19·97 ~singer Goldstein Delivers-State --::PieslAel1.till~. .·No·:~:Plans·'tlf·· Pr-oposes . ' '.' . OfThe CollegeAddress :~3nDg ByMingWong of'fulfillment, .. :..:.. ~..... .., ... RevampFor' College.Presi-. pr,oductivity By ..TaUlliql~·JiIaIr;.·. ':. dent Matthew and profes-"'-'~C9fiegitYPrfisld~ntMatthew CUNY Goldstein spokeof s ionali s m ". Goldsteinj~>~ontent'asBaruch the.importance of s . aid president"andhasno'plans'oftak- By Polly Gwardyak alumni contribu- GOldstein. i11gthecUrr~tlyvoid:CityUniver- Democratic mayoral candi tions towards the Despite tu- sity:.,ofNew.:YOrkChancellor posi- date Ruth Messinger outlined future growth of ition increases tion. her vision for CUNY at a speech Baruch College.in . of250 percent .··Goldsteit1.lut.s:servedasthePresi~ given at the Borough of Man the annual State in the past detltof·Baru~·COllege(or seven hattan Community College on of the College Ad-- -fiveyears, cut- ye~·!an4lia~·'1]e.eii·.tls1iedwith ~. ·.....::~·:~~~;~~~?'~:=f:~:t~;~ dress on October backsin fund- theprc>gresstne:'CollegeliiS'made -;\£'t 23. ..• Ing from AI- W1der.lp~j#$m-e'-btJ~ hefeelsthere Speaking in bany, the ter-, ~~~llW1pr()y~e~tstobemade, E~~t:=:l~~::riu;:~~lo~P:iI.U:e::: mainly adminis- an the De-~"'~;';~:':;:":';"'L\¥hiehsiatecfhis trators, faculty, ~ pa m of vim ."'edCityUIliver- and officials, PresldentGoIdstelngivinghis a ·i si~·.·;·:<' .... thtlle>Stateofthe Goldstein stressed State ofthe CollegeAddress.,.. .....,.. ressadded:totnore . .' . h _..... ~. ·3:;~~a·"~::':':ib6tit·m~;eart·:>':;'for how vital the alumnus IS to t e down sizing.in the :Of.-..•~ ... ",.,:::~ .. :::",,,;,..:,-,., ..,.,._,:-,,,.. ,.... --.~ t1ie?";":':I~~~':lm;~Buth.f:Sinil- College. -

The Title of This Online Course Or Retreat, and the Title of My Book, Is Really the Punchline of a Joke

Lama Surya Das Week Two, From Me to We June 8, 2015 “Inter-Meditation: How to Co-Meditate with Everyone and Everything” ©2015 Tricycle Magazine “Make Me One with Everything,” the title of this online course or retreat, and the title of my book, is really the punchline of a joke. The joke’s been around for a while. Maybe you’ve heard it? I think there are some profound meanings and levels to it, too. The Dalai Lama, who visits here quite regularly, and will be visiting New York City and California in July, for his eightieth birthday, is in the story. As the story goes, he was in the Bronx one day and he stopped for a snack at a hotdog vendor on the street, and he said, “Make me one with everything.” So that’s the joke. Of course, that’s a spiritual aspiration many of us share. I’ve added a few extra innings and we’ll talk about these different levels for separation, aspiration, and the importance of intention and motivation in this retreat. Anyway, so the hotdog vendor in his white t-shirt and his apron starts slathering up a hot dog with all the extras, and pouring on the mustard and sauce, and sauerkraut and relish. He hands it over to the maroon robed Dalai Lama, and the monk hands over a sawbuck, which is what we call a twenty dollar bill in Brooklyn. Then there’s a pregnant pause. Are they meditating? Is this a misunderstanding? A hotdog can’t cost twenty bucks. -

Petrology and Chemistry of Joe Lott Tuff Member of the Mount Belknap Volcanics, ---JL

Petrology and Chemistry of Joe Lott Tuff Member of the Mount Belknap Volcanics, ---JL. Marysvale Volcanic Field, West-Central Utah U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY PROFESSIONAL 1*APE:R 1354 Petrology and Chemistry of the Joe Lott Tuff Member of the Mount Belknap Volcanics, Marysvale Volcanic Field, West-Central Utah By KARIN E. BUDDING, CHARLES G. CUNNINGHAM, ROBERT A. ZIELINSKI, THOMAS A. STEVEN, and CHARLES R. STERN U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY PROFESSIONAL PAPER 1354 UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE, WASHINGTON : 1987 DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR DONALD PAUL HODEL, Secretary U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Dallas L. Peck, Director Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Petrology and chemistry of the Joe Lott Tuff Member of the Mount Belknap Volcanics, Marysvale volcanic field, west-central Utah. (Geological Survey professional paper ; 1354) Bibliography: p. Supt.ofDocs.no.: 119.16:1354 1. Volcanic ash, tuff, etc. Utah Marysvale region. I. Budding, Karin E. II. Series: Geological Survey professional paper ; 1354 QE461.P473 1987 552'.23 86-600023 For sale by the Books and Open-File Reports Section U.S. Geological Survey Federal Center Box 25425 Denver, CO 80225 PREFACE Joseph Augustus Lott, born March 10, 1855, was one of nine children of John Smiley Lott and his two wives, Mary Ann Faucett and Docia Emmerine Molen. John Lott was a soldier and settler for the Mormon Church. The Lott cabin, built by John in the mid-1870's, is located in Clear Creek Canyon just east of the mouth of Mill Creek and is typical of pioneer dwellings during Utah's territorial period. The homestead is significant because of its location on the Old Spanish Trail, which was a major trade route in Utah. -

'What's the Problem with Eureka?'

Bunny in the basket? – Eureka Springs Fire Department assisted the Easter Eggstravaganza Saturday afternoon by delicately dumping eggs from an Easter basket attached to the ladder truck. Starting at two, kids lined up to pick up eggs in a scramble to get as many in their baskets as they could find before they were gone. Pictured is Scott Dignan at the end of the ladder keeping the eggs cascading. Faith Christian Family Church hosted the event providing food, music and games to those who came out on the beautiful afternoon. PHOTOS BY JEREMIAH ALVARADO Council – Animal Ordinance 2 Independent Guestatorial 5 Astrology 7 Council – Wrap Up 2 Independent Mail 5 Independent Crossword 7 HDC 2 Top Tweets 5 Departure 8 Airport; WCCAD 3 The Nature of Eureka 6 Indy Soul 8 School Board 3 Hognobbing 6 Classified Materials 9 Diana Harvey 4 Sports Beat 6 Horseshoe Grill 10 Constables on Patrol 4 Dropping a Line 6 Dining Out 10 Inside the ESi Citizen wonders ‘what’s the problem with Eureka?’ HOLLY WESCOTT need to, as a community, come together, invite them in and Directly after Monday’s workshop, city council held a regular thank them for coming.” More information on this business can meeting starting with the unanimous ratification of Debbie Reay be found at www.turtlebackpark.com. to the City Advertising and Promotion Commission. She is co- Bob Jasinski then spoke, asking council why they were not owner of The Woods Cabins at 50 Wall Street. Also unanimously pursuing more mural and citywide wall art. He said Eureka’s approved were the re-appointments of Draxie Rogers and Steven signage is quickly fading away, stating “I don’t know what the Foster to the Parks & Recreation Commission. -

The Green Partnership Guide

12 STEPS TO HELP CREATE AN ENVIRONMENTALLY-FRI ENDLY SETTING FOR OUR GUESTS, FOR OURSELVES, AND FOR OUR FUTURE Author’s note: We are indebted to Ontario Hydro and to several departments of our federal and provincial governments as well as a number of universities and environmental organizations in Canada and the U.S.for much of the data which follows. Written by Warner Troyer 01992 Canadian Pacific Hotels & Resorts All cartoons 01992 by Tim Robertson. Printed on Recycled Paper.” Introduction: CPH&R Green Partnership Policy ................................................ 1 12 STEPS TO A GREENER PLANET Step 1: Reduce; Reuse; Recycle .................................................... 5 Step 2 Eliminate Excessive and Unnecessary Packaging ...... 8 Step 3: Eliminate All Aerosols & Phosphates ........................... 14 Step 4: Buy Recycled Paper Products Wherever Possible ...... 16 Step 5: Recycle Everything Possible & Practical ...................... 18 Step 6: Replace Incandescent Lights with Fluorescents......... 23 Step 7 Save our Precious Water ................................................... 27 Step 8: Buy Organic Foods Wherever Possible ........................ 33 Step 9: Establish a Guest Recycling Program ........................... 37 Step 10: Redistribute Used Amenities to Charity ...................... 39 Step 11: Establish a Toxic Waste Disposal Program .................. 41 Step 12: Establish a Green Corporate Purchasing Policy ......... 44 2 GREENING YOUR DEPARTMENT Introduction ...................................................................................... -

Stockholms Universitet Institutionen För Journalistik, Medier Och Kommunikation (JMK) Medie- Och Kommunikationsvetenskap

Stockholms universitet Institutionen för Journalistik, medier och kommunikation (JMK) Medie- och kommunikationsvetenskap Titel och undertitel: Rapmusikens mörka ansikte. – Glitter och stjärtar, fattigdom och hunger Nivå: C-uppsats (60 p) Författare: Ametist Azordegan Handledare: Mattias Ekman Termin: HT 2005 Rapmusikens Mörka Ansikte Glitter och stjärtar - fattigdom och hunger Sammanfattning Studiens övergripande syfte är att analysera maintream-raplåttexter och rapmusikvideor och utforska representationen av ideologiska strukturer i dessa. Detta görs med utgångspunkt i representationen av klass, etnicitet, kön och sexualitet. Studien relaterar till en diskussion om USA:s svarta befolknings livschanser och sociala förhållanden med den huvudsakliga frågeställningen: – Bidrar de ideologiska representationerna till att producera och reproducera sociala förhållanden? Och i så fall på vilket sätt? Den teoretiska ramen utgörs av teorier kring ideologisk hegemoni som kopplas samman med Horkheimer och Adornos marxistiska teorier om kulturindustrin som socialt cementerande samt Chomskys politisk-ekonomiska propagandamodell. Studiens berör även teorier kring den stereotypa representationen av svarta i medier genom historiskt-teoretiska beskrivningar av rasistiska ideologiers uppkomst och hur en särskild svart identitet har bildats, anammats och befästs. En kvalitativ tolkande metod används i studien med Faircloughs kritiska diskursanalys som huvudram vartefter det har utformats analysverktyg specifikt för denna studie. I studien dras slutsatsen -

Nelly Concert at Raley Field Postponed Until Thursday, October 18 the Hip-Hop Superstar Will Make a Stop in West Sacramento with Special Guest Fat Joe

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE August 6, 2018 Contact: Daniel Emmons, (916) 376-4850 Nelly concert at Raley Field postponed until Thursday, October 18 The hip-hop superstar will make a stop in West Sacramento with special guest Fat Joe West Sacramento, CA – Indigo Road Entertainment in association with the Sacramento River Cats announced today that the Nelly concert to be held at Raley Field with special guest Fat Joe has been postponed until Thursday, October 18 due to scheduling conflicts. Tickets start at $34 and can be purchased at rivercats.com the Round Table Ticket Office at Raley Field, or at ticketmaster.com. Questions regarding the postponement may be directed to [email protected] *** About the Sacramento River Cats The Sacramento River Cats are the Triple-A affiliate of the three-time World Champion San Francisco Giants. The team plays at Raley Field in West Sacramento, consistently voted one of the top ballparks in America. River Cats Season Tickets, Mini-Plans, and Flex Plans can be purchased for the upcoming 2018 season by calling the River Cats Ticket Hotline at (916) 371-HITS (4487). For more information about the River Cats, visit www.rivercats.com. For information on other events at Raley Field, visit www.raleyfield.com. About Nelly Diamond Selling, Multi-platinum, Grammy award-winning rap superstar, entrepreneur, philanthropist, and actor, Nelly, has continually raised the bar for the entertainment industry since stepping on the scene in 2000 with his distinctive vocals and larger-than-life personality. Nelly’s Country Grammar album and his song Cruise with FGL both achieved Diamond status in 2016. -

Newspaper $3.95

MAGAZINE TRADE COIN-OP THE Newspaper $3.95 0 82791 19359 8 VOL. LVII, NO. 10, OCTOBER 30, 1993 STAFF BOX GEORGE ALBERT President and Publisher FRED L. GOODMAN Editor In Chief MARK WAGNER Director, Nashville Operations CAMILLE COMPASIO Director, Coin Machine Operations MARKE TING/ADVER TISING JEROME A. MAS (LA) STAN LEWIS (NY) TIM SMITH (NASHVILLE) EDITORIAL INSIDE THE BOX TROY J. AUGUSTO. Assoc. Ed. (LA) MICHAEL MARTINEZ, Assoc. Ed. (LA) JOHN GOFF, Assoc. Ed. (LA) BRAD HOGUE, Nashville Editor COVER STORY KATHLEEN ERVIN, Assoc. Ed. (Nashville) CHART RESEARCH Steve Wariner: Drive To Survive SCOTT CHAMBLISS, Director of is with his latest Arista Nashville album, Drive. Cash Box Nashville editor Charts/Research Country music veteran Steve Wariner hot once again | DAVE DREWRY (LA) spoke with this Renaissance man about his career and music, especially his new single, "Drivin' And Cryin'" and live tour. ADAM TADESSE (LA) —see page 27 ROBIN HESS (Nashville) ALAN REITANO (Nashville) PRODUCTION Gold In Them Thar Hillbillies SAM DURHAM i If you liked the TV show, you'll probably love the movie. The Beverly Hillbillies, the film, is in the theatres, and Baby Boomers are CIRCULATION NINA TRF.GUB, Manager bringing their kids to enjoy the "fish-out-of-water" antics of the Clampett clan as they take on the "sacred cows" of the rich. PASHA SANTOSO —see page 8 PUBLICATION OFFICES NEW YORK Hall Of Fame Zaps Zappa 345 W. 58th Street Suite 15W New York, NY 10019 The Rock 'N' Roll Hall of Fame has named its latest inductees (see separate story on page 3). -

Views with Homeless Adults, I Examine How Homeless Persons Experience Policing

University of Alberta Homeless and policed: The racialized policing of homelessness, space, and mobility in Edmonton by Joshua Eugene Freistadt A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Sociology ©Joshua Freistadt Spring 2014 Edmonton, Alberta Permission is hereby granted to the University of Alberta Libraries to reproduce single copies of this thesis and to lend or sell such copies for private, scholarly or scientific research purposes only. Where the thesis is converted to, or otherwise made available in digital form, the University of Alberta will advise potential users of the thesis of these terms. The author reserves all other publication and other rights in association with the copyright in the thesis and, except as herein before provided, neither the thesis nor any substantial portion thereof may be printed or otherwise reproduced in any material form whatsoever without the author's prior written permission. Dedication “We may be homeless, but we are not heartless” -Staci, White homeless female “They don’t see the person that is fucking suffering. … I think people should be compassionate with each other.” -Carl, Aboriginal homeless male This research is dedicated to all the street-involved individuals who shared their stories with me. It is my sincere hope that their stories might change hearts, produce sympathy, multiply compassion, and inspire new responses to homelessness. Abstract The City of Edmonton recently developed an anti-panhandling bylaw and a diverted giving campaign. Previous literature on the policing of homelessness has focused on the development and discourses of these measures.