Objectives, but Also That Actors

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Serving Career and Technical Education Students in Pennsylvania

Career and Technical Student Organizations Serving Career and Technical Education Students in Pennsylvania 1 Dear CTSO Leaders, As the leader of a statewide trade association dedicated to the growth and development of the technology industry in Pennsylvania, I am keenly aware of the need for a highly-skilled, well-trained, and motivated workforce. At the Technology Council of Pennsylvania, we are strong advocates for advancements in and the promotion of S.T.E.M. education, as well as career and technical training, in order to prepare our young people to succeed in the 21st Century, global economy. That is why we support the work of Pennsylvania’s Career and Technical Student Organizations (CTSOs) and the critical role they play in today’s education community. For nearly 70 years, CTSOs have been able to extend teaching and learning through a variety of targeted programs, public-private partnerships and leadership development initiatives that produce technically advanced, employable students to meet the needs of this country’s diverse employer base. Today, the work of CTSOs has never been more valuable as our economy demands workers with a strong understanding of science, technology, engineering and math concepts as well as hands-on technical expertise. The co-curricular approach of CTSOs uniquely positions these organizations to enhance student skill sets and better prepare them to excel in their chosen careers. In order for Pennsylvania and the United States to not only compete, but succeed on a global stage, we need to ensure that the very technology and innovation companies that are driving this global economy have the availability of a well-qualified workforce. -

JV / Varsity Baseball Baseball Field at Bangor High School. Night Games at Bangor Park Jr

School Name: Bangor Area High School SPORT: CONTESTED AT: JV / Varsity Baseball Baseball Field at Bangor High School. Night Games at Bangor Park Jr. High / JV / Varsity Boy's Basketball Bill Pensyl Gymnasium at Bangor High School JV / Varsity Girl's Basketball Bill Pensyl Gymnasium at Bangor High School Middle School Girl's Basketball Bangor Middle School Gymnasium Cross Country Bangor High School JV / Varsity Field Hockey Field Hockey Field at Bangor High School. Middle School Field Hockey Field Hockey Field at Bangor Middle School. Middle School / JV / Varsity Football Paul Farnan Field At Bangor Memorial Park Stadium Golf Cherry Valley Golf Course. Stroudsburg PA. JV / Varsity Boy's & Girl's Soccer Soccer Field behind Bangor Middle School (afternoon games) JV / Varsity Boy's & Girl's Soccer Bangor Park (night games) JV / Varsity Softball Softball Field behind Bangor Middle School Tennis Bangor High School Tennis Courts Track & Field Paul Farnan Field at Bangor Memorial Park Stadium Jr. High / JV / Varsity Wrestling Bill Pensyl Gymnasium at Bangor high School Directions to Bangor High School (187 Five Points Richmond Road, Bangor PA.18013). From the Lehigh Valley: Route 33 north to Stockertown - Bangor exit. Pick up route 191 north into the town of Bangor. At the first stop light in town (VALERO GAS STATION ON THE LEFT) make a right onto Broadway. Go straight thru the first stop sign on Broadway and pick up Route 512 north. Follow route 512 for approximately 5 miles and you will come to a stop light (FIVE POINTS INTERSECTION). Make a right onto Five Points Richmond Road. -

Profile and Trends

Chapter 4 LAND DEVELOPMENT: Profi le and Trends Note: Refer to the following LVPC publications for more information on this subject: • Lehigh County Parks 2005 • Northampton County Parks 2010 • Lehigh Valley Greenways Plan — 2007 • Natural Areas Inventory Summary — 1999 • A Natural Areas Inventory of Lehigh and Northampton Counties, Pennsylvania — 1999, 2005 (Published by the Pennsylvania Science Offi ce of The Nature Conservan- cy) • Parks, Open Space and Outdoor Recreation Inventory - 2008, Lehigh and Northampton Counties • Bike Rides - The Lehigh Valley — 1994 • Lehigh Valley Trails Inventory - 2013 • 2012 Subdivision and Building Activity Report • An Affordable Housing Assessment of the Lehigh Valley — 2007 • Housing in the Lehigh Valley 2008 -47- TABLE 33 ESTIMATED EXISTING LAND USE — 2010 Wholesale & Trans., Comm. Public & Parks & Agriculture & Residential Commercial Industrial Warehousing & Utilities Quasi-Public Recreation Vacant Total Municipality Acres % Acres % Acres % Acres % Acres % Acres % Acres % Acres % Acres Alburtis 184 9 40 5 5 5 1 2 10 1 2 2 0 0 0 0 60 3 13 2 15 5 3 4 69 7 15 3 110 3 24 2 456 3 Allentown 3,514 2 30 5 846 8 7 3 866 2 7 5 30 4 0 3 2,946 0 25 5 864 0 7 5 1,577 7 13 7 889 8 7 7 11,535 1 Bethlehem (part) 1,033 3 36 8 331 9 11 8 233 7 8 3 9 8 0 3 802 6 28 6 143 2 5 1 121 9 4 3 134 7 4 8 2,811 1 Catasauqua 324 1 38 0 24 0 2 8 34 7 4 1 1 1 0 1 219 6 25 7 54 3 6 4 44 2 5 2 151 4 17 7 853 4 Coopersburg 268 2 44 8 61 8 10 3 18 2 3 0 1 0 0 2 85 3 14 2 32 2 5 4 24 8 4 1 107 2 17 9 598 7 Coplay 200 0 49 8 18 3 4 6 -

Email Us at [email protected]

JUNE 11, 2019 BLUE VALLEY TIMES COMMUNITY LISTINGS PAGE 13 NOTICE 10:45am Worship; Wed- 7pm Prayer/ 610-588-4648 Website) NOTICE included in the price. This is open to 19 from 10 AM to noon at Bryant Park, 4:00-?? at Weona Park, Rt 512, Pen To obtain a registration form ALL SUBMISSIONS MUST BE Bible Study. Rev. Jay VanHorn, Pastor www.flicksvilleucc.com Saturday 4 PM Sunday 8:30 AM St. Luke’s U.C.C. Belfast ALL SUBMISSIONS MUST BE all the public, including students. For 717 Bryant Street, Stroudsburg. Argyl. Please bring a finger food to please call (610) 759-7036, email Summer Worship at 10 a.m. Holy Days (See Church Website) EMAILED ONLY TO (610) 588-3966, 471 Belfast Rd., Nazareth (Belfast) EMAILED ONLY TO more information, please call Mary Lou In concert on July 2, 7:30 PM at the share, your own beverage and lawn [email protected], or visit www. www.crossroadbaptistbangor.org All are welcome! Saturday Confessions 3:25-3:45 PM SS 9am, Worship 10:30am. Rev. Frank DeRea-Lohman at 610-863-4846 or Pocono Mountain West High School chair. Listen and dance to the “Oldies” gbfcnaz.org. [email protected] [email protected] Gassler. 610-759-0244. 610-844-4630.” on Route 940, the concert is free to the and meet with friends. Everyone is BY FRIDAYS NOON BY FRIDAYS NOON The Lady’s Guild of Our Lady of Vic- God’s Missionary Church Portland Baptist Church www.stlukesuccbelfast.com public. welcome...RAIN OR SHINE ! Rummage Sale tory R.C. -

P&St at Baytoh

:-THursday, September 29, 1977 Ih caie of emergency reports tppics Dfoveti with careers dhd cbllfege call seen imi••T- : .., • '..'.. EVE.^ : '(Education(Education,, Thjhoe f«fe»e whli>tiwhich' InriurleIncludess . K«aKean College-Is:thCollene—Is the in- 376-0400 for Police Department Governor Brendan • Byrne: said this VocafioT^EmploymenO a vocational Interest testing structor. ThV.course will .1- or First Aid Squad The Early Childhood Department at week that thethances for congressional community service of fa S40,-- .' ' ' run on four Thursday^ 376^7670 for Fire Depart The Zip Code in-Union-will offer — —PrlpAa^fSam^Ky-i-nnBiinlBrg-fofegoods^: ^stock-.reported^a^0.7-percent rise~in±: Kean College^6f—New— "Get—-Ready—^For evenings " Sixty-Plus referral service for Springfield is workshops fprr teachers and other in- and services, iijr the "New York-' residential rents, computed bimonthly, \vdlte water treatment facilities, which Jersey, Union"Union,; Ta"s Collegel" ii a-four-sesslon ^beginning OcfTOTieTeels 07081 terested adults, Saturday, Oct. 15. -Northeastern NewJersey area rose .4 as Veil as higher prices. for,r could meaa-roore-than $500 million for scheduled, wprkshop for workshop geared to help $20. ___. ,• , . tj\.»_. I A . i. il housekeeping supplies and services. New Jersey over thtjnext; two-years,^ individuals who . are l h li t 8:30 a.m. in Willis Hall on the college -*ei«i . greatlfireatlvy inwove*iinprovedr—" v . • planning to cnange was reported by Herbert Bienstock, The fuel and utilities Index was up 0.5, 1 •campus. The workshops will end at regional, commissioner.of the U.S. percent with increases reported for fuel The Governor said he received the careers or go to college, or 12:45 p.m. -

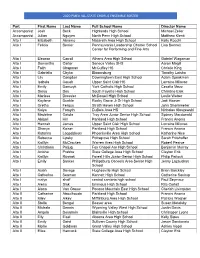

2020 Pmea All-State Chorus Ensemble Roster

2020 PMEA ALL-STATE CHORUS ENSEMBLE ROSTER Part First Name Last Name Full School Name Director Name Accompanist Josh Beck Highlands High School Michael Zeiler Accompanist Julian Nguyen North Penn High School Matthew Klenk Alto I Elizabeth Abramo Nazareth Area High School Kelly Rocchi Alto I Felicia Berrier Pennsylvania Leadership Charter School Lisa Bennett Center for Performing and Fine Arts Alto I Eleanor Carroll Athens Area High School Gabriel Wagaman Alto I Samantha Carter Seneca Valley SHS Aaron Magill Alto I Faith Chapman McGuffey HS Christie King Alto I Gabriella Chyko Bloomsburg Timothy Latsha Alto I Lily Congdon Downingtown East High School Adam Speakman Alto I Isabela Couoh Upper Saint Clair HS Lorraine Milovac Alto I Emily Danczyk York Catholic High School Cecelia Mezz Alto I Sreya Dey South Fayette High School Christine Elek Alto I Marissa Dressler McDowell High School Leslie Weber Alto I Kaylene Dunkle Rocky Grove Jr Sr High School Jodi Hoover Alto I Gretha Fergus Strath Haven High School John Shankweiler Alto I Kaiya Forsyth DuBois Area HS Nicholas Kloszewski Alto I Madeline Getola Troy Area Junior Senior High School Sydney Macdonald Alto I Abigail Hill Parkland High School Francis Anonia Alto I Hannah James Upper Saint Clair High School Lorraine Milovac Alto I Shanyn Kaiser Parkland High School Francis Anonia Alto I Katarina Lagodzinski Phoenixville Area High School Katharine Nice Alto I Rebecca Lipsky Pottsgrove High School Sarah Fritshaffer Alto I Kaitlyn McCracken Warren Area High School Robert Pearce Alto I Christiana -

Academic All-Star Breakfast

Palmerton Saucon Valley Mia Fantasia GPA: 4.45 Rank: 2 Sydney Oskin GPA: 4.659 Rank: 1 Sports Participation: Soccer, Track and Field Sports Participation: Swimming Academic Future Plans: Attend Penn State, majoring in Future Plans: Attend University of Notre Dame, Bachelor of Architecture Program. double-majoring in Engineering and Business. All-Star Jacob Martinez GPA: 4.36 Rank: 3 Evangelos Hahalis GPA: 4.652 Rank: 2 Sports Participation: Cross Country, Track and Field Sports Participation: Soccer, Lacrosse Future Plans: Attend Lehigh University, majoring in Future Plans: Attend University of Pittsburgh, Breakfast undeclared in the College of Arts and Sciences, majoring in Biology and Pre-Med participating in Cross County Pen Argyl Southern Lehigh Gabrielle Weaver GPA: 99.878 Rank: 14 Ellie Cassel GPA: 4.45 Rank: N/A Sports Participation: Field Hockey, Basketball, Sports Participation: Basketball, Soccer, Lacrosse, Softball Track and Field Future Plans: Attend Northampton Community Future Plans: Attend Wheaton College, participating in College, majoring in Environmental Science. Basketball. April 25, 2019 Tadd Barr GPA: 97.24 Rank: 25 Janik Wing GPA: 4.21 Rank: N/A Sports Participation: Football, Basketball, Track and Sports Participation: Swimming Field Future Plans: Attend Lehigh University, majoring in Future Plans: Attend Moravian College, majoring in Business and Engineering, participating in Swim Team Applied Math, participating in Football Salisbury Wilson Peyton Stauffer GPA: 101.47 Rank: 1 Sydney Gillen GPA: 118.71 Rank:2 Sports Participation: Field Hockey, Basketball, Sports Participation: Basketball, Cross Country, Track Softball and Field Future Plans: Attend Villanova University, majoring Future Plans: Attend University of Pennsylvania, in Biochemistry majoring in Biochemistry. -

2016Footballguide.Pdf

JJulieulie'n DDavenportavenport 1SSTT TTEAMEAM aabdullahbdullah JJulieulie'n AAlexlex BBenen aandersonnderson DDavenportavenport PPechinechin SSchumacherchumacher 1SSTT TTEAMEAM 1SSTT TTEAMEAM 1SSTT TTEAMEAM 1SSTT TTEAMEAM RETURNING ALL-PATRIOT LEAGUE SELECTIONS WWillill cartercarter MMarkark PylesPyles BBenen RichardRichard 2NNDD TTEAMEAM 2NNDD TTEAMEAM 2NNDD TTEAMEAM BBucknellucknell hhadad 1100 TTotalotal AAll-Patriotll-Patriot LLeagueeague SSelectionselections iinn 22015015 TABLE OF CONTENTS THE 2016 BISON BUCKNELL FOOTBALL HISTORY 2016 SCHEDULE Roster .......................................................................2-3 “A Century of Tradition” ...................................74-75 Sept. 3 at Marist 6 p.m. Roster Breakdown/Pronunciations .........................4 “Th e Top 10” ...................................................... 76-79 Sept. 10 at Duquesne 6 p.m. Depth Chart ............................................................... 5 Individual Records ............................................ 80-85 Sept. 17 CORNELL 6 p.m. Notebook .................................................................6-7 Team Records ...........................................................86 Sept. 24 VMI (FW) 3 p.m. Season Outlook ....................................................8-11 100-Yard Receivers/300-Yard Passers ...................87 Oct. 8 at Holy Cross* 1 p.m. Player Profi les..................................................... 12-41 100-Yard Rushers ...............................................88-89 Oct. 15 COLGATE* -

570-517-6596 Handy

APRIL 30, 2019 BLUE VALLEY TIMES PAGE 5 RN’S ODOOR I HOUT NC Cub Cadet•Kawasaki•Scag•Polaris•Ski-Doo•Can-Am•Husqvarna Our selection of off-road and lawn equipment includes Polaris ATVs, Ranger utility vehicles, and snowmobiles; Ski-Doo snowmobiles; Husqvarna power equipment and mowers, Can-Am ATVs, Spyders and UTV’s; Scag Commercial Mowers; Cub Cadet 2nd Place Bangor White Moravian Academy Gold Team Soils lawnmowers and tractors; Yamaha generators and preasure washers. Award Husqvarna Backpack Chain saw Blower 1169 MOUNT BETHEL HWY, MOUNT BETHEL PA 18343 Phone: (610) 588-6614 Fax: (610) 588-2343 email: [email protected] Hours: Mon, Tue, Fri 9-5, Wed, Thurs 9-6, Sat 9-1 www.hornsoutdoor.com HANDYHANDY MANMAN Tony’s SERVICE 3rd Place Freedom Black CB Award NeedNeed ThoseThose Odd Jobs Around 2019 Envirothon The House Done Today? Continued from page 1 Call MeToday! county event last year and placed 4th at the 2018 State competition; good luck Bangor! This year, seven schools competed with a total of thirteen teams from Bangor Area High School, Freedom High School, Nazareth Area High School, Northampton Area High School, Moravian Acad- I Do It All..... No Job Too Small! emy, Pen Argyl Area High School, and Saucon Valley High School. At the competition, the teams rotated through five stations taking written and hands-on tests. Painting Inside/Outside, Bangor Area High School Maroon Team - Donald Burham Taryn Geiger, Jeff Steinert, Angel Torres, and Veronika Xiao - had the highest cumulative score and was the 1st place winner. Bangor Area Light Plumbing/Electric, Carpeting High School White Team placed second, and Freedom High School Team Black placed third. -

2006 FREDDY Award Nominations

STATE THEATRE 2006 FREDDY© AWARD NOMINATIONS Nomination School Production Student Role/Song Bangor Area High School State Fair Emmaus High School Into the Woods Freedom High School Into the Woods Outstanding Performance by an Orchestra Liberty High School Fiddler on the Roof Parkland High School Beauty and the Beast Saucon Valley High School Beauty and the Beast Warren Hills High School The Music Man Allentown Central Catholic High School Fiddler on the Roof Caitlin McDermott Far From The Home I Love Catasauqua High School Little Shop of Horrors Tehya Berkner Somewhere That's Green Easton Area High School Barnum Savanah Simeone Black and White Outstanding Solo Vocal Performance Emmaus High School Into the Woods Katie Wexler On the Steps of the Palace Northampton High School Little Shop of Horrors Julia Damiani Somewhere That's Green Saucon Valley High School Beauty and the Beast Vince Rostkowski If I Can't Love Her Whitehall High School Barnum Bryna Gavin Thank God I'm Old Bangor Area High School State Fair Emmaus High School Into the Woods Outstanding Costume Freedom High School Into the Woods Design Parkland High School Beauty and the Beast Saucon Valley High School Beauty and the Beast Whitehall High School Barnum Belvidere High School Godspell Zack Hummer Zack Blair Academy High School How to Succeed in Business… Meg Fry Smitty Outstanding Performance Liberty High School Fiddler on the Roof Angela Colon Yente, the Matchmaker by a Featured Ensemble Parkland High School Beauty and the Beast Jon Lynch Le Fou Member Phillipsburg High -

Lehigh Valley Science Fair 2019 Awards List

Lehigh Valley Science Fair 2019 Awards List Senior Fair (A) - Behavior & Social Sciences (100) Del Award Project Val 1st Place A0101 The Difference Between Handwriting And Typing Notes For Memory Retention Havyn Steele - Bangor Area High School Sponsor - Robert Hachtman Senior Fair (A) - Computer (500) Del Award Project Val 1st Place A0501 Implementation Of Radio-Frequency Identification (RFID) Technology For Student Information Within Public School Buildings Gulnur Avci - Bangor Area High School Sponsor - Robert Hachtman Senior Fair (A) - Environmental (800) Del Award Project Val 1st Place A0802 The Effect Of Riparian Buffers Size On The Concentration Of Nitrate In Streams Rachel Kromer - Bangor Area High School Sponsor - Robert Hachtman Senior Fair (A) - Medicine & Health (1100) Del Award Project Val 1st Place A1101 Direct Aviation Of GABA Receptor By Citrus Aurantium Bergamia Utilizing Xenopus Laevis Oocytes Extracted Via Laparoscopic Surgery: Characterization Of A Novel Modulator Comparable To Benzodiazepines Sriyaa Suresh - Parkland High School Sponsor - Michael Post Senior Fair (A) - Microbiology (1200) Del Award Project Val 1st Place A1204 Effects OF Caffeine On Gut Bacteria Isabel Smith - Bangor Area High School Sponsor - Robert Hachtman 2nd Place A1203 The Importance Of Completing Your Antibiotic Regiment Morgan Shriver - Bangor Area High School Sponsor - Robert Hachtman Lehigh Valley Science Fair 2019 Awards List 3rd Place A1201 The Effects OF Sugar Alcohol On Gastrointestinal Normal Flora Nicola Kaye - Bangor Area High School -

OVERALL RANK SCHOOL 1 Hershey High School 2 Palmyra Area

OVERALL RANK SCHOOL 1 Hershey High School 2 Palmyra Area Senior High School 3 Tyrone Area High School 4 Cocalico Senior High School 5 Abington Heights High School 6 Wissahickon Senior High School 7 Fox Chapel Area High School 8 Elizabethtown Area Senior High School 9 Upper Saint Clair High School 10 Franklin Regional Senior High School 11 Blackhawk High School 12 Mariana Bracetti Academy Charter School 13 Saucon Valley Senior High School 14 North Penn Senior High School 15 Fairview High School 16 Palisades High School 17 Great Valley High School 18 Spring-Ford Senior High School 9-12 Center 19 Central Bucks High School -East 20 Shippensburg Area Senior High School 21 Valley View High School 22 Carbon Career & Technical Institute 23 Garden Spot Senior High School 24 Red Land Senior High School 25 Laurel Junior/Senior High School 26 Neshaminy High School 27 Strath Haven High School 28 Donegal High School 29 Springfield Township High School 30 Penn Manor High School 31 Penns Valley Area Junior/Senior High School 32 Karns City High School 33 Nazareth Area High School 34 Pennsbury High School 35 Ridley High School 36 West Chester Bayard Rustin High School 37 Wilson Area High School 38 Williamsport Area Senior High School 39 North Pocono High School 40 Perkiomen Valley High School 41 Marion Center Area Jr/Sr High School 42 Penn Cambria High School 43 Marple Newtown Senior High School 44 Susquehanna Community Junior/Senior High School 45 Charleroi Area High School 46 Danville Area Senior High School 47 North Allegheny High School 48 Clarion Area