Economies of Scales: Evolutionary Naturalists and the Victorian Examination System

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lettere Scritte Da Thomas Archer Hirst a Luigi Cremona Dal 1865 Al 1892 Conservate Presso L’Istituto Mazziniano Di Genova

LETTERE SCRITTE DA THOMAS ARCHER HIRST A LUIGI CREMONA DAL 1865 AL 1892 CONSERVATE PRESSO L’ISTITUTO MAZZINIANO DI GENOVA a cura di Giovanna Dimitolo www.luigi-cremona.it – luglio 2016 Indice Presentazione della corrispondenza 3 Criteri di edizione 3 Necrologio di Thomas Archer Hirst 4 Traduzione del necrologio di Thomas Archer Hirst 9 Il carteggio 14 Tabella – i dati delle lettere 83 Indice dei nomi citati nelle lettere 86 Bibliografia 92 2 Immagine di copertina: Thomas Archer Hirst (http://www-history.mcs.st-andrews.ac.uk/PictDisplay/Hirst.html) www.luigi-cremona.it – luglio 2016 Presentazione della corrispondenza La corrispondenza qui trascritta è composta da 84 lettere di Thomas Archer Hirst a Luigi Cremona e da 2 di Cremona a Hirst (una delle quali è probabilmente una bozza). La corrispondenza tra Hirst e Cremona racconta l’evoluzione di un profondo rapporto di amicizia tra i due matematici, della viva passione intellettuale che li accomuna e dell’ammirazione di Hirst per il collega italiano. Se nelle prime lettere vi sono molti richiami alle questioni matematiche, alle ricerche, alle pubblicazioni sulle riviste di matematiche, insieme a un costante rammarico per il poco tempo che Hirst può dedicare allo studio e un amichevole rimbrotto per gli incarichi politici di Cremona che lo distolgono dalla ricerca, man mano che passano gli anni, la corrispondenza diventa sempre più intima, vi compaiono le preoccupazioni per la salute declinante di Hirst, il dolore per la scomparsa prematura di persone care (il fratello e la prima moglie di Cremona, la nipote di Hirst), le vite degli amici comuni, i racconti dei viaggi e il desiderio sempre vivo di incontrarsi durante le vacanze estive o in occasione di conferenze internazionali. -

Recipients of Honoris Causa Degrees and of Scholarships and Awards Honoris Causa Degrees of the University of Melbourne*

Recipients of Honoris Causa Degrees and of Scholarships and Awards Honoris Causa Degrees of the University of Melbourne* MEMBERS OF THE ROYAL FAMILY 1868 His Royal Highness Prince Alfred Ernest Albert, Duke of Edinburgh (Edinburgh) LL.D. 1901 His Royal Highness Prince George Frederick Ernest Albert, Duke of York (afterwards King George V) (Cambridge) LL.D. 1920 His Royal Highness Edward Albert Christian George Andrew Patrick David, Prince of Wales (afterwards King Edward VIII) (Oxford) LL.D. 1927 His Royal Highness Prince Albert Frederick Arthur George, Duke of York (afterwards King George VI) (Cambridge) LL.D. 1934 His Royal Highness Prince Henry William Frederick Albert, Duke of Gloucester (Cambridge) LL.D. 1958 Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth, The Queen Mother (Oxford) LL.D. OTHER DISTINGUISHED GRADUATES 1914 Charles Greely Abbot (Massachusetts) D.Sc. Henry Edward Armstrong (Leipzig) D.Sc. William Bateson (Cambridge) D.Sc. William Morris Davis (Harvard) D.Sc. Frank Watson Dyson (Cambridge) D.Sc. Sir Thomas Henry Holland (Calcutta) D.Sc. Luigi Antonio Ettore Luiggi (Genoa) D.Sc. William Jackson Pope (Cambridge) D.Sc. Alfred William Porter (London) D.Sc. Sir Ernest Rutherford (Cambridge and New Zealand) D.Sc. Sir Edward Albert Schafer (London) D.Sc. Johannes Walther (Jena) D.Sc. 1915 Robert Randolph Garran (Sydney) M.A. Albert Bathurst Piddington (Sydney) M.A. 1918 Andre Siegfried (Paris) Litt.D. 1920 Sir William Riddell Birdwood (Cambridge) LL.D. Sir John Monash (Oxford and Cambridge) LL.D. 1927 Stanley Melbourne Bruce (Cambridge) LL.D. 1931 Charles Edwin Woodrow Bean (Oxford) Litt.D. 1932 Charles Herbert Fagge (London) M.D. 1934 Sir John Cadman (Birmingham) D.Eng. -

Models from the 19Th Century Used for Visualizing Optical Phenomena and Line Geometry

Models from the 19th Century used for Visualizing Optical Phenomena and Line Geometry David E. Rowe In 1891, one year after the founding of the Deutsche Mathematiker- Vereinigung (DMV), the Munich mathematician Walther Dyck faced a daunt- ing challenge. Dyck was eager to play an active role in DMV affairs, just as he had since 1884 as professor at Munich's Technische Hochschule (on his career, see [Hashagen 2003]). Thus he agreed, at first happily, to organize an exhibition of mathematical models and instruments for the forthcoming annual meeting of the DMV to be held in Nuremberg. Dyck's plan was ex- ceptionally ambitious, though he encountered many problems along the way. He hoped to obtain support for a truly international exhibition, drawing on work by model-makers in France, Russia, Great Britain, Switzerland, and of course throughout Germany. Most of these countries, however, were only modestly represented in the end, with the notable exception of the British. Dyck had to arrange for finding adequate space in Nuremberg for the exhibi- tion, paying for the transportation costs, and no doubt most time consuming of all, he had to edit single handedly the extensive exhibition catalog in time arXiv:1912.07138v1 [math.HO] 15 Dec 2019 for the opening. At the last moment, however, a cholera epidemic broke out in Germany that threatened to nullify all of Dyck's plans. When he learned that the DMV meeting had been canceled, he immediately proposed that the next annual gathering take place in 1893 in Munich. There he had both help- ful hands as well as ready access to the necessary infrastructure. -

The Royal Society of Chemistry Presidents 1841 T0 2021

The Presidents of the Chemical Society & Royal Society of Chemistry (1841–2024) Contents Introduction 04 Chemical Society Presidents (1841–1980) 07 Royal Society of Chemistry Presidents (1980–2024) 34 Researching Past Presidents 45 Presidents by Date 47 Cover images (left to right): Professor Thomas Graham; Sir Ewart Ray Herbert Jones; Professor Lesley Yellowlees; The President’s Badge of Office Introduction On Tuesday 23 February 1841, a meeting was convened by Robert Warington that resolved to form a society of members interested in the advancement of chemistry. On 30 March, the 77 men who’d already leant their support met at what would be the Chemical Society’s first official meeting; at that meeting, Thomas Graham was unanimously elected to be the Society’s first president. The other main decision made at the 30 March meeting was on the system by which the Chemical Society would be organised: “That the ordinary members shall elect out of their own body, by ballot, a President, four Vice-Presidents, a Treasurer, two Secretaries, and a Council of twelve, four of Introduction whom may be non-resident, by whom the business of the Society shall be conducted.” At the first Annual General Meeting the following year, in March 1842, the Bye Laws were formally enshrined, and the ‘Duty of the President’ was stated: “To preside at all Meetings of the Society and Council. To take the Chair at all ordinary Meetings of the Society, at eight o’clock precisely, and to regulate the order of the proceedings. A Member shall not be eligible as President of the Society for more than two years in succession, but shall be re-eligible after the lapse of one year.” Little has changed in the way presidents are elected; they still have to be a member of the Society and are elected by other members. -

MAUVE and ITS ANNIVERSARIES* Anthony S

Bull. Hist. Chem., VOLUME 32, Number 1 (2007) 35 MAUVE AND ITS ANNIVERSARIES* Anthony S. Travis, Edelstein Center, Hebrew University of Jerusalem/Leo Baeck Institute London Introduction chemical constitution of the natural dye indigo, as well as other natural products. Of particular interest, however, In 1856, William Henry Perkin in were the components of, and pos- London prepared the first aniline sible uses for, the vast amount of dye, later known as mauve. The coal-tar waste available from coal- eighteen-year-old inventor sought, gas works and distilleries. Around but failed, to find a licensee for 1837, Liebig’s assistant A. Wilhelm his process, and then embarked Hofmann extracted several nitro- on manufacture, with the back- gen-containing oils from coal tar ing of his father and a brother. and showed that of these bases the The opening of their factory and one present in greatest abundance the sudden demand for mauve in was identical with a product earlier 1859 foreshadowed the growth obtained from indigo as well as of the modern organic chemical from other sources. It was soon industry. The search throughout known as aniline. Europe for novel colorants made In 1845 Hofmann moved to scientific reputations and trans- London to head the new Royal Col- formed the way in which research lege of Chemistry (RCC). There he was conducted, in both academic continued his studies into aniline and industrial laboratories. Ac- and its reactions. At that time, there cordingly, the sesquicentennial William Henry Perkin (1838-1907), in 1860. Heinrich Caro (1834-1910), technical leader were no modern structural formulae of mauve provides an opportune at BASF, 1868-1889. -

The Founding of the London Mathematical Society in 1865

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Elsevier - Publisher Connector HISTORIA MATHEMATICA 22 (1995), 402-421 From Student Club to National Society: The Founding of the London Mathematical Society in 1865 ADRIAN C. RICE,* ROBIN J. WILSON,'}" AND J. HELEN GARDNERt *School of Mathematics and Statistics, Middlesex University, Bounds Green, London Nil 2NG, England; and t Faculty of Mathematics and Computing, The Open University, Walton Hall, Milton Keynes MK7 6AA, England In this paper we describe the events leading to the founding of the London Mathematical Society in 1865, and discuss the progress of the Society throughout its first two years. ©1995 Academic Press, Inc. Dans cet article nous d6crivons les 6vbnements qui menaient h la fondation de la Soci6t6 math6matique de Londres (London Mathematical Society) en 1865, et nous examinons l'6volu- tion de la Soci6t6 tout au long de ses deux premibres ann6es. ©1995 AcademicPress, Inc. In dieser Arbeit beschreiben wir die Ereignisse, die zu der Grtindung der London Mathemat- ical Society (LMS) in 1865 geftihrt haben, und besprechen wir die Entwicklung der LMS w~ihrend den ersten zwei Jahren ihrer Existenz. ©1995 AcademicPress, Inc. MSC 1991 subject classification: 01A55. KEY WORDS:London Mathematical Society, University College, London, Augustus De Morgan. 1. INTRODUCTION Throughout the 19th century, science became more specialized than ever before. In Britain, as elsewhere in Europe, this was reflected in the growing dissatisfaction with the established scientific societies. The Royal Society, founded in 1662 to encourage research in the natural and physical sciences, had come under increasing criticism from prominent scientists for its monopolistic position. -

Mathematics in the Metropolis: a Survey of Victorian London

HISTORIA MATHEMATICA 23 (1996), 376±417 ARTICLE NO. 0039 Mathematics in the Metropolis: A Survey of Victorian London ADRIAN RICE School of Mathematics and Statistics, Middlesex University, Bounds Green, View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk London N11 2NQ, United Kingdom brought to you by CORE provided by Elsevier - Publisher Connector This paper surveys the teaching of university-level mathematics in various London institu- tions during the reign of Queen Victoria. It highlights some of the famous mathematicians who were involved for many years as teachers of this mathematics, including Augustus De Morgan, James Joseph Sylvester, and Karl Pearson. The paper also investigates the wide variety of teaching establishments, including mainly academic institutions (University College, King's College), the military colleges (Royal Military Academy, Woolwich and Royal Naval College, Greenwich), the women's colleges (Bedford and Queen's), and the technical colleges and polytechnics (e.g., Central Technical Institute) which began to appear during the latter part of this period. A comparison of teaching styles and courses offered is a fruitful way of exploring the rich development of university-level mathematics in London between 1837 and 1901. 1996 Academic Press, Inc. Cet ouvrage examine dans son ensemble l'enseignement matheÂmatique au niveau universi- taire dans diverses institutions aÁ Londres pendant la reÁgne de la Reine Victoria. Nous soulig- nons quelques matheÂmaticiens ceÂleÁbres qui participeÁrent dans ce milieu, par exemple, Au- gustus De Morgan, James Joseph Sylvester, et Karl Pearson. En plus, nous analysons les diverses grandes eÂcoles d'enseignement, y compris surtout des institutions acadeÂmiques (Uni- versity College, King's College), des eÂcoles militaires (Royal Military Academy, Woolwich et Royal Naval College, Greenwich), des eÂcoles de femmes (Bedford et Queen's), et des eÂcoles techniques et polytechniques (par exemple, Central Technical Institute) qui commencËaient aÁ apparaõÃtre durant la dernieÁre partie de cette peÂriode. -

Durham E-Theses

Durham E-Theses The development of the teaching of chemistry in England, 1799-1853 Byrne, Michael S. How to cite: Byrne, Michael S. (1968) The development of the teaching of chemistry in England, 1799-1853, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/9867/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk ABSTBACT OP THESIS THE DEVEL0PI4iSi\'T OF THE TEACHING OF CHEMISTHY IN* BiJGLAWDj 1799-1853 o The thesis traces the developnent of chemistiy^ teaching in England set against the scientific and educational development of the period» At the end of the eighteenth centuiy, chemistzy was little studied and then only as an adjunct to other professional studieso Chemistry as a profession did not exist and there were no laboratories in which a student could receive a practical training. -

Lettere Scritte Da Thomas Archer Hirst a Luigi Cremona Dal 1865 Al 1892 Conservate Presso L’Istituto Mazziniano Di Genova

LETTERE SCRITTE DA THOMAS ARCHER HIRST A LUIGI CREMONA DAL 1865 AL 1892 CONSERVATE PRESSO L’ISTITUTO MAZZINIANO DI GENOVA a cura di Giovanna Dimitolo www.luigi-cremona.it – luglio 2016 Indice Presentazione della corrispondenza 3 Criteri di edizione 3 Necrologio di Thomas Archer Hirst 4 Traduzione del necrologio di Thomas Archer Hirst 9 Il carteggio 14 Tabella – i dati delle lettere 83 Indice dei nomi citati nelle lettere 86 Bibliografia 92 2 Immagine di copertina: Thomas Archer Hirst (http://www-history.mcs.st-andrews.ac.uk/PictDisplay/Hirst.html) www.luigi-cremona.it – luglio 2016 Presentazione della corrispondenza La corrispondenza qui trascritta è composta da 84 lettere di Thomas Archer Hirst a Luigi Cremona e da 2 di Cremona a Hirst (una delle quali è probabilmente una bozza). La corrispondenza tra Hirst e Cremona racconta l’evoluzione di un profondo rapporto di amicizia tra i due matematici, della viva passione intellettuale che li accomuna e dell’ammirazione di Hirst per il collega italiano. Se nelle prime lettere vi sono molti richiami alle questioni matematiche, alle ricerche, alle pubblicazioni sulle riviste di matematiche, insieme a un costante rammarico per il poco tempo che Hirst può dedicare allo studio e un amichevole rimbrotto per gli incarichi politici di Cremona che lo distolgono dalla ricerca, man mano che passano gli anni, la corrispondenza diventa sempre più intima, vi compaiono le preoccupazioni per la salute declinante di Hirst, il dolore per la scomparsa prematura di persone care (il fratello e la prima moglie di Cremona, la nipote di Hirst), le vite degli amici comuni, i racconti dei viaggi e il desiderio sempre vivo di incontrarsi durante le vacanze estive o in occasione di conferenze internazionali. -

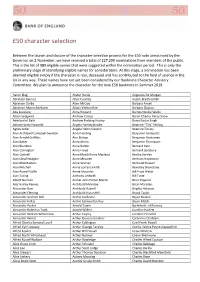

50 Character Selection

£50 character selection Between the launch and closure of the character selection process for the £50 note announced by the Governor on 2 November, we have received a total of 227,299 nominations from members of the public. This is the list of 989 eligible names that were suggested within the nomination period. This is only the preliminary stage of identifying eligible names for consideration: At this stage, a nomination has been deemed eligible simply if the character is real, deceased and has contributed to the field of science in the UK in any way. These names have not yet been considered by our Banknote Character Advisory Committee. We plan to announce the character for the new £50 banknote in Summer 2019. Aaron Klug Alister Hardy Augustus De Morgan Abraham Bennet Allen Coombs Austin Bradford Hill Abraham Darby Allen McClay Barbara Ansell Abraham Manie Adelstein Alliott Verdon Roe Barbara Clayton Ada Lovelace Alma Howard Barnes Neville Wallis Adam Sedgwick Andrew Crosse Baron Charles Percy Snow Aderlard of Bath Andrew Fielding Huxley Bawa Kartar Singh Adrian Hardy Haworth Angela Hartley Brodie Beatrice "Tilly" Shilling Agnes Arber Angela Helen Clayton Beatrice Tinsley Alan Archibald Campbell‐Swinton Anita Harding Benjamin Gompertz Alan Arnold Griffiths Ann Bishop Benjamin Huntsman Alan Baker Anna Atkins Benjamin Thompson Alan Blumlein Anna Bidder Bernard Katz Alan Carrington Anna Freud Bernard Spilsbury Alan Cottrell Anna MacGillivray Macleod Bertha Swirles Alan Lloyd Hodgkin Anne McLaren Bertram Hopkinson Alan MacMasters Anne Warner -

Abstract Reduction of Ketones to Alcohols And

ABSTRACT REDUCTION OF KETONES TO ALCOHOLS AND TERTIARY AMINES USING 1-HYDROSILATRANE Sami E. Varjosaari, Ph.D. Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry Northern Illinois University, 2018 Marc J. Adler, Co-Director Thomas M. Gilbert, Co-Director 1-Hydrosilatrane is an easily synthesized, stable, solid silane which can be made into an efficient reducing agent in the presence of a Lewis base, by taking advantage of the properties of hypervalent silicon. Due to the simplicity of use and handling, 1-hydrosilatrane has the potential to be an appealing alternative to other more widely used reducing agents. Aromatic and aliphatic ketones were readily reduced with 1-hydrosilatrane in the presence of potassium tert-butoxide. The discovery of diastereoselectivity in the reduction of menthone, a chiral ketone, led to enantioselective reductions of prochiral ketones using chiral Lewis base activators. Enantiomeric excesses of up to 86% were observed. It was also shown that 1-hydrosilatrane could act as a chemoselective reducing agent in the formation of tertiary amines via direct reductive aminations, in the absence of activator or solvent. Attempts were also made to take advantage of the steric properties of silicon protecting groups in meta-directing electrophilic aromatic substitution of phenols, leading to a one-pot synthesis of O-aryl carbamates. i NORTHERN ILLINOIS UNIVERSITY DEKALB, ILLINOIS MAY 2018 REDUCTION OF KETONES TO ALCOHOLS AND TERTIARY AMINES USING 1-HYDROSILATRANE BY SAMI ENSIO VARJOSAARI ©2018 SAMI ENSIO VARJOSAARI A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY DEPARTMENT OF CHEMISTRY AND BIOCHEMISTRY Doctoral Co-Directors: Marc J. -

Nature Vol 140-N3534.Indd

140 NATURE jl:LY 24, 1937 Obituary Notices Prof. H. E. Armstrong, F.R.S. College, South Kensington, where a novel type of ENRY EDWARD ARMSTRONG, whose death institution came into being, self-governed academic H on July 13 in his ninetieth year we regret to ally by its four professors-{)hemistry, engineering, announce, was born on May 6, 1848, in Lewisham, mathematics and physics-and independent of ex where he lived all his life. Of the influences during ternal examiners, which rapidly grew to be recognized his early youth which inclined him to chemistry, as a great professional school of engineering. But in little is known, but when he left Colfe's Grammar 1911, when the City and Guilds College by incorpora School at Lewisham his father, acting on the advice tion became the engineering section of the Imperial of an engineering friend, allowed him to become a College of Science and Technology, its chemistry and student at the Royal College of Chemistry, Oxford mathematics departments were closed down, although Street, in the summer term of 1865, actually Hof provision was made for chemistry diploma students mann's last term before his departure for Berlin. to finish their course under Armstrong's supervision Chemistry was the only subject taught, but the with its completion, chemistry ceased to be taught College was affiliated to the Royal School of Mines, in the City and Guilds College, and the last of the then housed in Jermyn Street. A free lance, he laboratories of the department was dismantled in attended such courses at the two institutions as he 1914.