Iran: Trampling Humanity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Freedom of Assembly and Association

JANUARY 2012 COUNTRY SUMMARY Iran In 2011 Iranian authorities refused to allow government critics to engage in peaceful demonstrations. In February, March, April, and September security forces broke up large- scale protests in several major cities. In mid-April security forces reportedly shot and killed dozens of protesters in Iran’s Arab-majority Khuzestan province. There was a sharp increase in the use of the death penalty. The government continued targeting civil society activists, especially lawyers, rights activists, students, and journalists. In July 2011 the government announced it would not cooperate with, or allow access to, the United Nations special rapporteur on Iran, appointed in March 2011 in response to the worsening rights situation. Freedom of Assembly and Association In February and March thousands of demonstrators took to the streets of Tehran, the capital, and several other major cities to support pro-democracy protests in neighboring Arab countries and protest the detention of Iranian opposition leaders. The authorities’ violent response led to at least three deaths and hundreds of arrests. In response to calls by former presidential candidates and opposition leaders Mir Hossein Mousavi and Mehdi Karroubi for mass protests in February, security forces arbitrarily arrested dozens of political opposition members in Tehran and several other cities beginning on February 8. Several days later they placed both Mousavi and Karroubi under house arrest, where they remained at this writing. In April Iran’s parliament passed several articles of a draft bill which severely limits the independence of civil society organizations, and creates a Supreme Committee Supervising NGO Activities chaired by ministry officials and members of the security forces. -

The Combined Use of Long-Term Multi-Sensor Insar Analysis and Finite Element Simulation to Predict Land Subsidence

The International Archives of the Photogrammetry, Remote Sensing and Spatial Information Sciences, Volume XLII-4/W18, 2019 GeoSpatial Conference 2019 – Joint Conferences of SMPR and GI Research, 12–14 October 2019, Karaj, Iran THE COMBINED USE OF LONG-TERM MULTI-SENSOR INSAR ANALYSIS AND FINITE ELEMENT SIMULATION TO PREDICT LAND SUBSIDENCE M. Gharehdaghi 1,*, A. Fakher 2, A. Cheshomi 3 1 MSc. Student, School of Civil Engineering, College of Engineering, University of Tehran, Tehran, Iran – [email protected] 2 Civil Engineering Department, University of Tehran, Tehran, Iran – [email protected] 3 Department of Engineering Geology, School of Geology, College of Science, University of Tehran, Tehran, Iran - [email protected] KEY WORDS: Land Subsidence, Ground water depletion, InSAR data, Numerical Simulation, Finite Element Method, Plaxis 2D, Tehran ABSTRACT: Land subsidence in Tehran Plain, Iran, for the period of 2003-2017 was measured using an InSAR time series investigation of surface displacements. In the presented study, land subsidence in the southwest of Tehran is characterized using InSAR data and numerical modelling, and the trend is predicted through future years. Over extraction of groundwater is the most common reason for the land subsidence which may cause devastating consequences for structures and infrastructures such as demolition of agricultural lands, damage from a differential settlement, flooding, or ground fractures. The environmental and economic impacts of land subsidence emphasize the importance of modelling and prediction of the trend of it in order to conduct crisis management plans to prevent its deleterious effects. In this study, land subsidence caused by the withdrawal of groundwater is modelled using finite element method software Plaxis 2D. -

Molecular Identification of Toxoplasma Gondii in the Native Slaughtered Cattle of Tehran Province, Iran A

Journal of Food Quality and Hazards Control 6 (2019) 153-161 Molecular Identification of Toxoplasma gondii in the Native Slaughtered Cattle of Tehran Province, Iran A. Dalir Ghaffari 1,2, A. Dalimi 1* 1. Department of Parasitology, Faculty of Medical Sciences, Tarbiat Modares University, Tehran, Iran 2. Student Research Committee, Faculty of Medical Sciences, Tarbiat Modares University, Tehran, Iran HIGHLIGHTS Genotype III was the most prevalent genotype of Toxoplasma gondii in slaughtered cattle of Tehran, Iran. The infection rate in heart muscle samples (16.66%) was significantly higher than the diaphragm samples (4.44%). The frequency of T. gondii in cattle muscles was high in this area. Article type ABSTRACT Original article Background: Toxoplasmosis, caused by Toxoplasma gondii, is a common parasitic Keywords disease, affecting almost one-third of the world’s population. It is transmitted by Toxoplasma ingestion of food or water contaminated with oocysts excreted by cats and the Polymerase Chain Reaction Meat consumption of raw or undercooked meat from ruminants. This study aimed at molecular Cattle characterization of T. gondii in native cattle from West of Tehran, Iran. Iran Methods: A total of 180 samples were collected from the cattle diaphragms (n=80) and heart muscles (n=100) from multiple slaughterhouses. The nested Polymerase Chain Article history Received: 14 Aug 2019 Reaction (PCR) assay was carried out to amplify the GRA6 gene of T. gondii. The Revised: 10 Oct 2019 PCR-Restriction Fragment Length Polymerase (PCR-RFLP) assay was also performed on Accepted: 27 Oct 2019 positive samples, using Tru1I (MseI) restriction enzyme. Data were statistically analyzed using SPSS (v.15.0). -

The IRGC in the Age of Ebrahim Raisi: Decision-Making and Factionalism in Iran’S Revolutionary Guard

The IRGC in the Age of Ebrahim Raisi: Decision-Making and Factionalism in Iran’s Revolutionary Guard SAEID GOLKAR AUGUST 2021 KASRA AARABI Contents Executive Summary 4 The Raisi Administration, the IRGC and the Creation of a New Islamic Government 6 The IRGC as the Foundation of Raisi’s Islamic Government The Clergy and the Guard: An Inseparable Bond 16 No Coup in Sight Upholding Clerical Superiority and Preserving Religious Legitimacy The Importance of Understanding the Guard 21 Shortcomings of Existing Approaches to the IRGC A New Model for Understanding the IRGC’s Intra-elite Factionalism 25 The Economic Vertex The Political Vertex The Security-Intelligence Vertex Charting IRGC Commanders’ Positions on the New Model Shades of Islamism: The Ideological Spectrum in the IRGC Conclusion 32 About the Authors 33 Saeid Golkar Kasra Aarabi Endnotes 34 4 The IRGC in the Age of Ebrahim Raisi Executive Summary “The Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps [IRGC] has excelled in every field it has entered both internationally and domestically, including security, defence, service provision and construction,” declared Ayatollah Ebrahim Raisi, then chief justice of Iran, in a speech to IRGC commanders on 17 March 2021.1 Four months on, Raisi, who assumes Iran’s presidency on 5 August after the country’s June 2021 election, has set his eyes on further empowering the IRGC with key ministerial and bureaucratic positions likely to be awarded to guardsmen under his new government. There is a clear reason for this ambition. Expanding the power of the IRGC serves the interests of both Raisi and his 82-year-old mentor, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, the supreme leader of the Islamic Republic. -

Tainted Peace: Torture in Sri Lanka Since May 2009

Tainted Peace: Torture in Sri Lanka since May 2009 in Sri Lanka Torture Peace: Tainted Tainted Peace: Torture in Sri Lanka since May 2009 Freedom from Torture August 2015 Torture Freedom from Freedom from Torture 111 Isledon Road London N7 7JW Registered charity no: England 1000340, Scotland SC039632 Freedom from Torture August 2015 Front cover photo: A Sri Lankan soldier stands in front of a war monument in Kilinochchi, Sri Lanka. Back cover photo: A Tamil, who is a survivor of torture at the hands of Sri Lankan security forces, displays significant burns on his back. Photos: Will Baxter http://willbaxter.photoshelter.com Freedom from Torture Freedom from Torture is the only UK-based human rights organisation dedicated to the treatment and rehabilitation of torture survivors. We do this by offering services across England and Scotland to around 1,000 torture survivors a year, including psychological and physical therapies, forensic documentation of torture, legal and welfare advice, and creative projects. Since our establishment in 1985, more than 57,000 survivors of torture have been referred to us, and we are one of the world’s largest torture treatment centres. Our expert clinicians prepare medico-legal reports (MLRs) that are used in connection with torture survivors’ claims for international protection, and in research reports, such as this, aimed at holding torturing states to account. We are the only human rights organ- isation in the UK that systematically uses evidence from in-house clini- cians, and the torture survivors they work with, to hold torturing states accountable internationally; and to work towards a world free from torture. -

IRAN EXECUTIVE SUMMARY the Islamic Republic of Iran

IRAN EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The Islamic Republic of Iran is a constitutional, theocratic republic in which Shia Muslim clergy and political leaders vetted by the clergy dominate the key power structures. Government legitimacy is based on the twin pillars of popular sovereignty--albeit restricted--and the rule of the supreme leader of the Islamic Revolution. The current supreme leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, was chosen by a directly elected body of religious leaders, the Assembly of Experts, in 1989. Khamenei’s writ dominates the legislative, executive, and judicial branches of government. He directly controls the armed forces and indirectly controls internal security forces, the judiciary, and other key institutions. The legislative branch is the popularly elected 290-seat Islamic Consultative Assembly, or Majlis. The unelected 12-member Guardian Council reviews all legislation the Majlis passes to ensure adherence to Islamic and constitutional principles; it also screens presidential and Majlis candidates for eligibility. Mahmoud Ahmadinejad was reelected president in June 2009 in a multiparty election that was generally considered neither free nor fair. There were numerous instances in which elements of the security forces acted independently of civilian control. Demonstrations by opposition groups, university students, and others increased during the first few months of the year, inspired in part by events of the Arab Spring. In February hundreds of protesters throughout the country staged rallies to show solidarity with protesters in Tunisia and Egypt. The government responded harshly to protesters and critics, arresting, torturing, and prosecuting them for their dissent. As part of its crackdown, the government increased its oppression of media and the arts, arresting and imprisoning dozens of journalists, bloggers, poets, actors, filmmakers, and artists throughout the year. -

Iran 2019 International Religious Freedom Report

IRAN 2019 INTERNATIONAL RELIGIOUS FREEDOM REPORT Executive Summary The constitution defines the country as an Islamic republic and specifies Twelver Ja’afari Shia Islam as the official state religion. It states all laws and regulations must be based on “Islamic criteria” and an official interpretation of sharia. The constitution states citizens shall enjoy human, political, economic, and other rights, “in conformity with Islamic criteria.” The penal code specifies the death sentence for proselytizing and attempts by non-Muslims to convert Muslims, as well as for moharebeh (“enmity against God”) and sabb al-nabi (“insulting the Prophet”). According to the penal code, the application of the death penalty varies depending on the religion of both the perpetrator and the victim. The law prohibits Muslim citizens from changing or renouncing their religious beliefs. The constitution also stipulates five non-Ja’afari Islamic schools shall be “accorded full respect” and official status in matters of religious education and certain personal affairs. The constitution states Zoroastrians, Jews, and Christians, excluding converts from Islam, are the only recognized religious minorities permitted to worship and form religious societies “within the limits of the law.” The government continued to execute individuals on charges of “enmity against God,” including two Sunni Ahwazi Arab minority prisoners at Fajr Prison on August 4. Human rights nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) continued to report the disproportionately large number of executions of Sunni prisoners, particularly Kurds, Baluchis, and Arabs. Human rights groups raised concerns regarding the use of torture, beatings in custody, forced confessions, poor prison conditions, and denials of access to legal counsel. -

Torture's Link to Profit in Sri Lanka, a Retrospective Review

28 SCIENTIFIC ARTICLE Mercy for money: Torture’s link to profit in Sri Lanka, a retrospective review Wendell Block, M.D.,* Jessica Lee M.D.,* Kera Vijayasingham B.A.* between 1989 and 2013. We tallied the Key points of interest: number of incidents in which claimants • This paper supplements earlier studies described paying cash or jewelry to end on prevalence of bribe payments to end torture, and collected other associated data torture in Sri Lanka, adding trends such as demographics, organizations of the throughout the war, after the war, perpetrators, locations, and, if available, involving multiple armed organizations, amounts paid. We included torture perpe- and across wide geographic locations. trated by both governmental and nongovern- • Victims may not genuinely be consid- mental militant groups. Collected data was ered to be a security risk but are used for coded and evaluated. Findings: We found extortion. that 78 of the 95 subjects (82.1%) whose • Significant economic and social impact reported ordeals met the United Nations on families is likely. Convention Against Torture/International • Torture unlikely to stop until financial Criminal Court definitions of torture incentives are removed. described paying to end torture at least once. • High prevalence suggests that perpetra- 43 subjects paid to end torture more than tors act in collusion with their superiors once. Multiple groups (governmental and and benefit from impunity. non-governmental) practiced torture and extorted money by doing so. A middleman Abstract was described in 32 percent of the incidents. Background: The purpose of this retro- Payment amounts as reported were high spective study is to describe the pattern of compared to average Sri Lankan annual bribe taking in exchange for release from incomes. -

Search Results

Showing results for I.N. BUDIARTA RM, Risks management on building projects in Bali Search instead for I.N. BUDIARTHA RM, Risks management on building projects in Bali Search Results Volume 7, Number 2, March - acoreanajr.com www.acoreanajr.com/index.php/archive?layout=edit&id=98 Municipal waste cycle management a case study: Robat Karim County .... I.N. Budiartha R.M. Risks management on building projects in Bali Items where Author is "Dr. Ir. Nyoman Budiartha RM., MSc, I NYOMAN ... erepo.unud.ac.id/.../Dr=2E_Ir=2E__Nyoman_Budiart... Translate this page Jul 19, 2016 - Dr. Ir. Nyoman Budiartha RM., MSc, I NYOMAN BUDIARTHA RM. (2015) Risks Management on Building Projects in Bali. International Journal ... Risks Management on Building Projects in Bali - UNUD | Universitas ... https://www.unud.ac.id/.../jurnal201605290022382.ht... Translate this page May 29, 2016 - Risks Management on Building Projects in Bali. Abstrak. Oleh : Dr. Ir. Nyoman Budiartha RM., MSc. Email : [email protected]. Kata kunci ... [PDF]Risk Management Practices in a Construction Project - ResearchGate https://www.researchgate.net/file.PostFileLoader.html?id... ResearchGate 5.1 How are risks and risk management perceived in a construction project? 50 ... Risk management (RM) is a concept which is used in all industries, from IT ..... structure is easy to build and what effect will it have on schedule, budget or safety. Missing: budiarta bali [PDF]Risk management in small construction projects - Pure https://pure.ltu.se/.../LTU_LIC_0657_SE... Luleå University of Technology by K Simu - Cited by 24 - Related articles The research school Competitive Building has also been invaluable for my work .... and obstacles for risk management in small projects are also focused upon. -

“We Will Make You Regret Everything”

“We will make you Torture in Iran since regret everything” the 2009 elections Freedom from Torture Country Reporting Programme March 2013 Freedom from Torture Country Reporting Programme March 2013 “We will make you regret everything” Torture in Iran since the 2009 elections “Why did this happen to me, what did I do wrong? ...They’ve made me hate my body to a point that I don’t want to shower or get dressed... I feel alone and can’t trust another person.” Case study - Sanaz, page 6 3 Table of Contents Summary and key findings ............................................................. 7 Key findings of the report .................................................................... 8 Recommendations .......................................................................... 10 Introduction ................................................................................... 11 Freedom from Torture’s history of working with Iranian torture survivors 11 Case sample and method ..................................................................... 11 1. Case Profile ............................................................................................ 12 a. Place of origin and place of residence when detained .................................. 12 b. Ethnicity and religious identity .............................................................. 12 c. Ordinary occupation .......................................................................... 13 d. History of activism or dissent .............................................................. -

Ali Kazemy T (+98) 863 624 1261 U (+98) 863 622 7814 B [email protected] Curriculum Vitae Í

Department of Electrical Engineering Tafresh University, Tafresh, Iran Ali Kazemy T (+98) 863 624 1261 u (+98) 863 622 7814 B [email protected] Curriculum Vitae Í http://faculty.tafreshu.ac.ir/kazemy/en Education 2007–2013 Doctor of Philosophy, Iran University of Science and Technology, Tehran, Iran. Electrical Engineering, Control 2004–2007 Master of Science, Iran University of Science and Technology, Tehran, Iran. Electrical Engineering, Control PhD Dissertation Title Robust Stability of Continuous-Time Lur’e Systems with Multiple Constant Time- delays Supervisor Professor Mohammad Farrokhi Masters Thesis Title Design and Simulation of Intelligent Image Control in Three-Degrees-of-Freedom Periscope with Implementation on an Experimental Setup Supervisor Professor Mohammad Farrokhi Description This thesis was specifically defined on a submarine periscope and successfully implemented on an experimental setup at Malek-Ashtar University of Technology. Employment History 2013–Present Assistant Professor, Department of Electrical Engineering, Tafresh University, Tafresh, Iran. 2014–Present Head of Short-term Training Courses, Tafresh University, Tafresh, Iran. 2017–Present Head of Incubator Center, Tafresh University, Tafresh, Iran. Miscellaneous 2006–2013 Chief Executive Officer (CEO), Bargh Afzar Farzam Company, Tehran, Iran. 2007–2008 Lecturer, Iran Petroleum Training Center, Tehran, Iran. Visiting & Research Positions 2019 Research Associate, Three months from 20th of May to 20th Aug, at the invitation of Professor James Lam (grant 69000 HK$), The University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong. 1/5 Honors and Awards 2019 The Best Researcher, Markazi Province. 2019 The Best Researcher, Tafresh University. 2018 The Best Researcher (Triennial), Tafresh University. 2018 The Best Researcher (Yearly), Tafresh University. 2017 Selected Researcher, Tafresh University. -

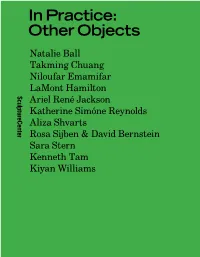

In Practice: Other Objects

In Practice: Other Objects Natalie Ball Takming Chuang Niloufar Emamifar LaMont Hamilton Ariel René Jackson Katherine Simóne Reynolds Aliza Shvarts Rosa Sijben & David Bernstein Sara Stern Kenneth Tam Kiyan Williams In Practice: Other Objects All rights reserved, including rights of reproduction in whole or in part in any form. © SculptureCenter and the authors Published by SculptureCenter 44-19 Purves Street Long Island City, NY 11101 +1 718 361 1750 [email protected] www.sculpture-center.org ISBN: 978-0-9998647-4-6 Design: Chris Wu, Yoon-Young Chai, and Ella Viscardi at Wkshps Copy Editor: Lucy Flint Printer: RMI Printing, New York All photographs by Kyle Knodell, 2019 unless otherwise noted. 2 SculptureCenter In Practice: Other Objects 3 Natalie Ball In Practice: With a foundation in visual archives, materiality, gesture, and historical research, I make art as proposals of refusal to complicate an easily affirmed Other Objects and consumed narrative and identity without absolutes. I am interested in examining internal and external discourses that shape American history and Indigenous identity to challenge historical discourses that have constructed a limited and inconsistent visual archive. Playing Dolls is a series of assemblage sculptures as Power Objects that are influenced by the paraphernalia and aesthetics of a common childhood activity. In Practice: Other Objects presents new work by eleven artists and artist teams Using sculptures and textile to create a space of reenactment, I explore modes who probe the slippages and interplay between objecthood and personhood. of refusal and unwillingness to line up with the many constructed mainstream From personal belongings to material evidence, sites of memory, and revisionist existences that currently misrepresent our past experiences and misinform fantasies, these artists isolate curious and ecstatic moments in which a body current expectations.