Science and the Search for the First Americans Robert

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Quaternary Geology of the Tule Springs Area, Clark County, Nevada

Quaternary geology of the Tule Springs area, Clark County, Nevada Item Type text; Dissertation-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Haynes, C. Vance (Caleb Vance), 1928- Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 27/03/2021 04:29:29 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/565093 QUATERNARY GEOLOGY OF THE TULE SPRINGS AREA, CLARK COUNTY, NEVADA by \«V Ct Vance Haynes, Jr. A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the DEPARTMENT OF GEOLOGY In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 1 9 6 5 THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA GRADUATE COLLEGE I hereby recommend that this dissertation prepared under my direction by Caleb Vance Haynes, Jr.______________________ entitled Quater n a r y Geology of the Tule Springs Area, Clark County, Nevada___________________________ be accepted as fulfilling the dissertation requirement of the degree of _____ Doctor of Philosophy_________________________ Dissertation Director Date After inspection of the dissertation, the following members of the Final Examination Committee concur in its approval and recommend its acceptance:* c *This approval and acceptance is contingent on the candidate's adequate performance and defense of this dissertation at the final oral examination. The inclusion of this sheet bound into the library copy of the dissertation is evidence of satisfactory performance at the final examination. -

Plains Anthropologist Author Index

Author Index AUTHOR INDEX Aaberg, Stephen A. (see Shelley, Phillip H. and George A. Agogino) 1983 Plant Gathering as a Settlement Determinant at the Pilgrim Stone Circle Site. In: Memoir 19. Vol. 28, No. (see Smith, Calvin, John Runyon, and George A. Agogino) 102, pp. 279-303. (see Smith, Shirley and George A. Agogino) Abbott, James T. Agogino, George A. and Al Parrish 1988 A Re-Evaluation of Boulderflow as a Relative Dating 1971 The Fowler-Parrish Site: A Folsom Campsite in Eastern Technique for Surficial Boulder Features. Vol. 33, No. Colorado. Vol. 16, No. 52, pp. 111-114. 119, pp. 113-118. Agogino, George A. and Eugene Galloway Abbott, Jane P. 1963 Osteology of the Four Bear Burials. Vol. 8, No. 19, pp. (see Martin, James E., Robert A. Alex, Lynn M. Alex, Jane P. 57-60. Abbott, Rachel C. Benton, and Louise F. Miller) 1965 The Sister’s Hill Site: A Hell Gap Site in North-Central Adams, Gary Wyoming. Vol. 10, No. 29, pp. 190-195. 1983 Tipi Rings at York Factory: An Archaeological- Ethnographic Interface. In: Memoir 19. Vol. 28, No. Agogino, George A. and Sally K. Sachs 102, pp. 7-15. 1960 Criticism of the Museum Orientation of Existing Antiquity Laws. Vol. 5, No. 9, pp. 31-35. Adovasio, James M. (see Frison, George C., James M. Adovasio, and Ronald C. Agogino, George A. and William Sweetland Carlisle) 1985 The Stolle Mammoth: A Possible Clovis Kill-Site. Vol. 30, No. 107, pp. 73-76. Adovasio, James M., R. L. Andrews, and C. S. Fowler 1982 Some Observations on the Putative Fremont Agogino, George A., David K. -

Geochronology of Sandia Cave

^/ MA Geochronology of Sandia Cave 4? jp^^gj^^F* 'W SMlTHSQNIAN bONTRltffi^ONS TO ANTHROPOLOGY • ^UAmJ/ 0 Mp ,v * •. •'-•• SERIES PUBLICATIONS OF THE SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION Emphasis upon publication as a means of "diffusing knowledge* was expressed by the first Secretary of the Smithsonian. In his formal plan for the Institution. Joseph Henry outlined a program that included the following statement: "It is proposed to publish a series of reports, giving an account of the new discoveries in science, and of the changes made from year to year in all branches of knowledge." This theme of basic research has been adhered to through the years by thousands of titles issued in series publications under the Smithsonian imprint, commencing with Smithsonian Contributions to Knowledge in 1848 and continuing with the following active series: Smithsonian Contributions to Anthropology Smithsonian Contributions to Astrophysics Smithsonian Contributions to Botany Smithsonian Contributions to the Earth Sciences Smithsonian Contributions to the Marine Sciences Smithsonian Contributions to Paleobiology Smithsonian Contributions to Zoology Smithsonian Folklife Studies Smithsonian Studies in Air and Space Smithsonian Studies in History and Technology In these series, the Institution publishes small papers and full-scale monographs that report the research and collections of its various museums and bureaux or of professional colleagues in the world of science and scholarship. The publications are distributed by mailing lists to libraries, universities, and similar institutions throughout the world. Papers or monographs submitted for series publication are received by the Smithsonian Institution Press, subject to its own review for format and style, only through departments of the various Smithsonian museums or bureaux, where the manuscripts are given substantive review. -

Mathematics and Architecture of the Incas in Peru

AC 2011-2240: MATHEMATICS AND ARCHITECTURE OF THE INCAS IN PERU Cheri Shakiban, University of St. Thomas I am a professor of mathematics at the University of St. Thomas in St. Paul, Minnesota, where I have been a faculty member since 1983. I received my Ph.D. in 1979 from Brown University in Formal Cal- culus of Variations. My recent area of research is mostly in computer vision, with applications to object recognition. My publications are in diverse areas of mathematics and engineering. I love to work with undergraduate students, in particular, underrepresented students, to get them involved in doing research in mathematics and encourage them to give conference presentations/posters and submit their work for publication. In addition to teaching regular math courses, I also like to create and teach innovative courses such as ”Mathematical symmetry of Southern Spain” and ”Mathematics and Architecture of the Incas in Peru”, which I have taught as study abroad courses several times. Michael P. Hennessey, University of St. Thomas Michael P. Hennessey (Mike) joined the full-time faculty as an Assistant Professor fall semester 2000. He is an expert in machine design, computer-aided-engineering, and in the kinematics, dynamics, and control of mechanical systems, along with related areas of applied mathematics. Presently, he has published 41 technical papers (published or accepted), in journals (9), conferences (31), or magazines (1). In 2006 he was tenured and promoted to the rank of Associate Professor. Mike gained 10 years of industrial and academic research lab experience at 3M, FMC, and the University of Minnesota prior to embarking on an academic career at Rochester Institute of Technology (3 years) and Minnesota State University, Mankato (2 years). -

CALLAO, PERU Onboard: 1800 Saturday November 26

Arrive: 0800 Tuesday November 22 CALLAO, PERU Onboard: 1800 Saturday November 26 Brief Overview: A traveler’s paradise, the warm arms of Peru envelope some of the world’s most timeless traditions and greatest ancient treasures! From its immense biodiversity, the breathtaking beauty of the Andes Mountains (the longest in the world!) and the Sacred Valley, to relics of the Incan Empire, like Machu Picchu, and the rich cultural diversity that populates the country today – Peru has an experience for everyone. Located in the Lima Metropolitan Area, the port of Callao is just a stone’s throw away from the dazzling sights and sounds of Peru’s capital and largest city, Lima. With its colorful buildings teeming with colonial architecture and verdant coastline cliffs, this vibrant city makes for a home-away-from-home during your port stay in Peru. Nearby: Explore Lima’s most iconic neighborhoods - Miraflores and Barranco – by foot, bike (PER 104-201 Biking Lima), and even Segway (PER 121-101 Lima by Segway). Be sure to hit up one of the local markets (PER 114-201 Culinary Lima) and try out Peruvian fare – you can’t go wrong with picarones (fried pumpkin dough with anis seeds and honey - pictured above), cuy (guinea pig), or huge ears of roast corn! Worth the travel: Cusco, the former capital of Incan civilization, is a short flight from Lima. From this ancient city, you can access a multitude of Andean wonders. Explore the ruins of the famed Machu Picchu, the city of Ollantaytambo – which still thrives to this day, Lake Titcaca and its many islands, and the culture of the Quechua people. -

Copyrighted Material Not for Distribution

Contents List of Figures ix List of Tables xvii 1 Stones, Bones, and Profiles: Archaeology and Geoarchaeology of C. V. Haynes Jr. and George C. Frison Marcel Kornfeld and Bruce B. Huckell 3 Part I. Peopling of North America and Paleoindians 2 Confessions of a Clovis Mafioso Stuart J. Fiedel 29 3 Why the Ice-Free Corridor Is Still Relevant to the Peopling of the New World COPYRIGHTED MATERIAL Andrea Freeman NOT 51 FOR DISTRIBUTION 4 Tracking the First People of Mexico: A Review of the Archaeological Record Guadalupe Sanchez and John Carpenter 75 5 Use-Wear Analysis of Clovis Bifaces from the Gault Site, Texas Ashley M. Smallwood and Thomas A. Jennings 103 6 Younger Dryas Archaeology and Human Experience at the Paisley Caves in the Northern Great Basin Dennis L. Jenkins, Loren G. Davis, Thomas W. Stafford Jr., Thomas J. Connolly, George T. Jones, Michael Rondeau, Linda Scott Cummings, Bryan Hockett, Katelyn McDonough, Patrick W. O’Grady, Karl J. Reinhard, Mark E. Swisher, Frances White, Robert M. Yohe II, Chad Yost, and Eske Willerslev 127 Part II. Geoarchaeology 7 Soils and Stratigraphy of the Lindenmeier Site Vance T. Holliday 209 8 Mammoth Potential: Reinvestigating the Union Pacific Mammoth Site, Wyoming Mary M. Prasciunas, C. Vance Haynes Jr., Fred L. Nials, Lance McNees, William E. Scoggin, and Allen Denoyer 235 9 Late Holocene Geoarchaeology in the Bighorn Basin, Wyoming Judson Byrd Finley 259 COPYRIGHTEDPart III. Bison BoneMATERIAL Bed Stud ies NOT10 Folsom FOR Biso DISTRIBUTIONn Hunting on the Southern Plains of North America Leland Bement and Brian Carter 291 11 Bison by the Numbers: Late Quaternary Geochronology and Bison Evolution on the Southern Plains Eileen Johnson and Patrick J. -

Younger Dryas ‘‘Black Mats’’ and the Rancholabrean Termination in North America

Younger Dryas ‘‘black mats’’ and the Rancholabrean termination in North America C. Vance Haynes, Jr.* Departments of Anthropology and Geosciences, PO Box 210030, University of Arizona, Tucson, AZ 85721 Contributed by C. Vance Haynes, Jr., January 23, 2008 (sent for review April 27, 2007) Of the 97 geoarchaeological sites of this study that bridge the nor are they known to be associated with any major climatic Pleistocene-Holocene transition (last deglaciation), approximately perturbation as was the case with YD cooling. two thirds have a black organic-rich layer or ‘‘black mat’’ in the form of mollic paleosols, aquolls, diatomites, or algal mats with Stratigraphy and Climate Change radiocarbon ages suggesting they are stratigraphic manifestations Stratigraphic sequences can reflect climate change in that of the Younger Dryas cooling episode 10,900 B.P. to 9,800 B.P. lacustrine or paludal sediments such as marls or diatomites (radiocarbon years). This layer or mat covers the Clovis-age land- indicate ponding or emergent water tables and some mollisols or scape or surface on which the last remnants of the terminal aquolls indicate shallow water tables with capillary fringes Pleistocene megafauna are recorded. Stratigraphically and chro- approaching or reaching the surface. Such conditions support nologically the extinction appears to have been catastrophic, plant growth and thereby increase the organic content of wetland seemingly too sudden and extensive for either human predation or or cienega soils collectively referred to as black mats. Many of the climate change to have been the primary cause. This sudden black mats discussed here occur in eolian silt or fine sand (loess) ؎ Rancholabrean termination at 10,900 50 B.P. -

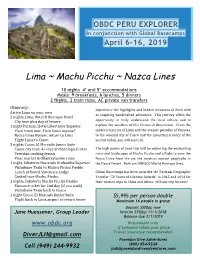

Lima ~ Machu Picchu ~ Nazca Lines

OBDC PERU EXPLORER In conjunction with Global Basecamps April 6-16, 2019 Lima ~ Machu Picchu ~ Nazca Lines 10 nights 4* and 5* accommodations Meals: 9 breakfasts, 6 lunches, 5 dinners 2 flights, 2 train rides, AC private van transfers Itinerary: Experience the highlights and hidden treasures of Peru with Arrive Lima on your own an inspiring handcrafted adventure. This journey offers the 2 nights Lima, Hotel B Boutique Hotel City tour plus day of leisure opportunity to truly understand the local culture and to 1 night Paracas, Hotel LiBertador Superior explore the wonders of this historical destination. From the Pisco town tour, Pisco Sours anyone? modern luxuries of Lima and the seaside paradise of Paracas, Nazca Lines flyover, return to Lima to the colonial city of Cusco and the mountain scenery of the Flight Lima to Cusco Sacred Valley, you will see it all. 3 nights Cusco, El Mercado Junior Suite Cusco city tour, 4+ Inca archaeological sites The high points of your trip will Be exploring the enchanting Peruvian cooking lesson ruins and landscapes of Machu Picchu and a flight to view the Pisac market & OllantaytamBo ruins Nazca Lines from the air, the mystical ancient geoglyphs in 1 night, Inkaterra Hacienda UruBamBa Superior the Nazca Desert. Both are UNESCO World Heritage Sites. Vistadome Train to Machu Picchu PueBlo Lunch at famed Sanctuary Lodge GloBal Basecamps has Been awarded the National Geographic Guided tour Machu Picchu Traveler “50 Tours of Lifetime Awards” in 2015 and 2014 for 2 nights, Inkaterra Machu Picchu PueBlo their custom trips to China and Africa. -

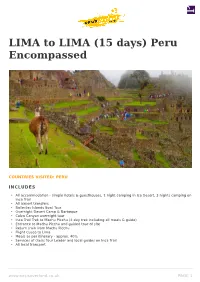

LIMA to LIMA (15 Days) Peru Encompassed

LIMA to LIMA (15 days) Peru Encompassed COUNTRIES VISITED: PERU INCLUDES • All accommodation - simple hotels & guesthouses, 1 night camping in Ica Desert, 3 nights camping on Inca Trail • All airport transfers • Ballestas Islands Boat Tour • Overnight Desert Camp & Barbeque • Colca Canyon overnight tour • Inca Trail Trek to Machu Picchu (4 day trek including all meals & guide) • Entrance to Machu Picchu and guided tour of site • Return train from Machu Picchu • Flight Cusco to Lima • Meals as per itinerary - approx. 40% • Services of Oasis Tour Leader and local guides on Inca Trail • All local transport www.oasisoverland.co.uk PAGE 1 [email protected] Tel: +44 (0)203 725 8924 EXCLUDES • Visas • National Park entrance fees totalling approx. $30 USD • International Flights • Meals not listed in the itinerary • Travel Insurance • Airport Taxes • Drinks • Optional Excursions as listed in the Pre-Departure Information • Tips TRIP ITINERARY DAYS 1 LIMA The capital of Peru, Lima is a city of contrasts. Here you'll encounter both abundant wealth and grinding poverty, modern skyscrapers next to some of the finest museums and historical monuments in Latin America. You will have a free day to explore its many museums, markets and colonial plazas. Visit the Old Town as well as the Miraflores district before watching the sunset over the Pacific Ocean at the end of the day.(No Meals) Overnight: Hotel Buena Vista (or similar) DAYS 2 LIMA TO BALLESTAS ISLANDS Our first stop, south of Lima, is the Ballestas Islands in the Paracas National Reserve. Here we take a boat trip to view one of the most important marine reserves in the world with the highest concentration of rare and exotic sea birds and sea mammals. -

Paleoindian and Archaic Periods

ADVANCED SOUTHWEST ARCHAEOLOGY THE PALEOINDIAN AND ARCHAIC PERIODS PURPOSE To present members with an opportunity to acquire an in-depth understanding of the Paleoindian and Archaic periods as their occupations are viewed broadly across North America with a focus on the Southwest. OBJECTIVES After studying the manifestation of the Paleoindian and Archaic periods in the Southwest, the student is to have an in-depth understanding of the current thinking regarding: A. Arrival of the first Americans and their adaptation to various environments. Paleoenvironmental considerations. B. Archaeology of the Paleoindian and Archaic periods in the Southwest and important sites for defining and dating the occupations. Synthesis of the Archaic tradition within the Southwest. Manifestation of the Paleoindian and Archaic occupations of the Southwest in the archaeological record, including recognition of Paleoindian and Archaic artifacts and features in situ and recognition of Archaic rock art. C. Subsistence, economy, and settlement strategies of the Paleoindian and Archaic periods in the Southwest. D. Transition from Paleoindian to Archaic, and from Archaic to major cultural traditions including Hohokam, Anasazi, Mogollon, Patayan, and Sinagua, or Salado, in the Southwest. E. Introduction of agriculture in the Southwest considering horticulture and early cultigens. F. Lithic technologies of the Paleoindian and Archaic periods in the Southwest. FORMAT Twenty-five hours of classwork are required to present the class. Ten classes of two and one-half hours -

Hidden Mysteries of Peru

Peru HIDDEN MYSTERIES OF PERU 13 Days FROM $3,389 Ancient Inca Circular Terraces in Moray Puno HOSTED PROGRAM PROGRAM HIGHLIGHTS (2) Lima • (2) Puerto Maldonado • (3) Sacred Valley • (2) Cusco • (2) Puno • (1) Paracas •Stay in an authentic lodge and have amazing ecological adventures in Puerto Maldonado •Have the experience of a lifetime exploring the lost city of the Incas – Machu Picchu, Peru’s most important archeological site and one of the new Seven Wonders of the World ECUADOR •Explore Cusco’s Koricancha Temple and Sacsayhuaman Fortress •Get to know pre-Inca culture at Taquile Island, 12,000 feet above sea level PERU BRAZIL •Sail to the famous Uros Islands, man-made floating islands in the middle of Lake Titicaca National Reserve Lima 2 Machu Picchu •See the mysterious Nazca lines on a flight over 2 Puerto Maldonado Sacred Valley 3 the enormous outlines of stylized plants, animals, 2 Cusco and shapes scattered on the desert floor that has Paracas 1 remained undisturbed for 2000 years Puno 2 DAY 1 I LIMA Arrive in Lima and transfer to your hotel. Afternoon is at leisure. DAYS 2 – 3 I LIMA I PUERTO MALDONADO Private transfer to Lima airport to board your flight to Puerto Maldonado. Upon arrival, # - No. of Overnight Stays Arrangements by transfer to your lodge. For the next two days, enjoy activities including: DAY 12 I LIMA I PARACAS I NAZCA LINES Early transfer to the bus Concepcion Rainforest Trails, Twilight Canoe Cruise on Madre de Dios station to board your bus to Paracas. Upon arrival in Paracas transfer to HIDDEN MYSTERIES OF PERU River, Lake Sandoval hike, Inkaterra Canopy Walkway over 7 treetop your hotel. -

S41598-021-84653-4.Pdf

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN The human EDAR 370V/A polymorphism afects tooth root morphology potentially through the modifcation of a reaction–difusion system Keiichi Kataoka1,2, Hironori Fujita3,4,5, Mutsumi Isa1, Shimpei Gotoh1,2, Akira Arasaki2, Hajime Ishida1 & Ryosuke Kimura1* Morphological variations in human teeth have long been recognized and, in particular, the spatial and temporal distribution of two patterns of dental features in Asia, i.e., Sinodonty and Sundadonty, have contributed to our understanding of the human migration history. However, the molecular mechanisms underlying such dental variations have not yet been completely elucidated. Recent studies have clarifed that a nonsynonymous variant in the ectodysplasin A receptor gene (EDAR 370V/A; rs3827760) contributes to crown traits related to Sinodonty. In this study, we examined the association between the EDAR polymorphism and tooth root traits by using computed tomography images and identifed that the efects of the EDAR variant on the number and shape of roots difered depending on the tooth type. In addition, to better understand tooth root morphogenesis, a computational analysis for patterns of tooth roots was performed, assuming a reaction–difusion system. The computational study suggested that the complicated efects of the EDAR polymorphism could be explained when it is considered that EDAR modifes the syntheses of multiple related molecules working in the reaction–difusion dynamics. In this study, we shed light on the molecular mechanisms of tooth root morphogenesis, which are less understood in comparison to those of tooth crown morphogenesis. Morphological variations in human teeth have been well studied in the feld of dental anthropology 1,2.