Codifying the Criminal Law

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Charging Language

1. TABLE OF CONTENTS Abduction ................................................................................................73 By Relative.........................................................................................415-420 See Kidnapping Abuse, Animal ...............................................................................................358-362,365-368 Abuse, Child ................................................................................................74-77 Abuse, Vulnerable Adult ...............................................................................78,79 Accessory After The Fact ..............................................................................38 Adultery ................................................................................................357 Aircraft Explosive............................................................................................455 Alcohol AWOL Machine.................................................................................19,20 Retail/Retail Dealer ............................................................................14-18 Tax ................................................................................................20-21 Intoxicated – Endanger ......................................................................19 Disturbance .......................................................................................19 Drinking – Prohibited Places .............................................................17-20 Minors – Citation Only -

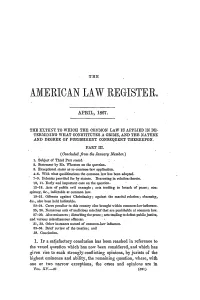

Extent to Which the Common Law Is Applied in Determining What

THE AMERICAN LAW REGISTER, APRIL, 1867. THE EXTE'N"IT TO WHICH THE COM ON LAW IS APPLIED IN DE- TERMINING WHAT CONSTITUTES A CRIME, AND THE NATURE AND DEGREE OF PUNISHMENT CONSEQUENT THEREUPON. PART III. (Concluded from the January.umber.) 1. Subject of Third. Part stated. 2. Statement by .Mr. Wheaton on tie question. 3. Exceptional states as to common-law application. 4-6. With what qualifications the common law has been adopted. 7-9. Felonies provided for by statute. Reasoning in relation thereto. 10, 11. Early and important case on the question. 12-18. Acts of public evil example; acts tending to breach of peace; con- -piracy, &c., indictable at common law. 19-21. Offences against Christianity; against the marital relation; obscenity, &c., also been held indictable. 22-24. Cases peculiar to this country also brought within common-law influence. 25, 26. 'Numerous acts of malicious mischief that are punishable at common law. 27-30. Also nuisances ; disturbing the peace; acts tenxding to defeat public justice. and various miscellaneous offences. 31, 32. Other instances named of common-law influence. 33-36. Brief review of the treatise; and 38. Conclusion. 1. IF a satisfactory conclusion has been reached in reference to the vexed question which has now been considered, and which has given rise to such strongly-conflicting opinions, by jurists of the highest eminence and ability, the remaining question, where, with one or two narrow exceptions, the eases and opinions are in VOL. XV.-21 (321) APPLICATION OF THE COMMON LAW almost perfect accord, cannot be attended with much difficulty. -

Legal Drafting at the European Commission: Documentation

LEGAL DRAFTING AT THE EUROPEAN COMMISSION: DOCUMENTATION Mr. William Robinson Coordinator in the Legal Revisers Group European Commission's Legal Service Contents Page Outline 1 Rules on drafting 2 Model act with notes: Commission Regulation 3 OUTLINE Introduction: Drafting of EC legislation •Official languages •EC legislation •Drafting in the European Commission Multilingual drafting in the European Commission •Community legislative acts shall be drafted clearly, simply and precisely. •Consistent terminology •Provisions of acts shall be concise. Respect the principle of multilingualism •Use direct forms •Avoid short cuts •Keep the sentence structure simple •Mind your grammar •Choose your words with care •Solutions to drafting problems must work in all the languages. Training of European Commission drafters •Functions of revisers •Qualifications •Basic rulebook Practical training •Teamwork •‘Apprenticeship’ •Supervision •Consolidating best practices Formal training •Introductory courses for drafters •Legal Service courses and other Commission courses •Seminars on quality of legislation •Other sources of expertise Background Documentation Mr Robinson-for repro.doc RULES RELEVANT TO THE DRAFTING OF LEGAL ACTS Declaration No 39 on the quality of the drafting of Community legislation, adopted by the Intergovernmental Conference in Amsterdam on 2 October 1997 (OJ C 340, 10.11.1997, p. 139) Interinstitutional Agreement of 22 December 1998 on common guidelines for the quality of drafting of Community legislation (OJ C 73, 17.3.1999, p. 1) Interinstitutional Agreement of 16 December 2003 on better law-making (OJ C 321, 31.12.2003, p. 1) Joint Practical Guide signed on 16 March 2000 Accessible from: http://eur-lex.europa.eu/en/techleg/index.htm Interinstitutional Style Guide http://publications.europa.eu/code/en/en-000100.htm CODIFICATION AND RECASTING Interinstitutional Agreement of 20 December 1994 on an accelerated working method for official codification of legislative texts (OJ C 102, 4.4.1996, p. -

Lng Carrier Voyage Charter Party

LNG CARRIER VOYAGE CHARTER PARTY BETWEEN __________________________________ AS OWNER AND _________________________________ AS CHARTERER GIIGNL LNGVOY 16 May 2012 DISCLAIMER This document was drafted only for the purpose of serving as a reference and the user is required to use it at its sole discretion and responsibility. GIIGNL and all of its members hereby disclaim any direct or indirect liability as to information contained in this document for any industrial, commercial or other use whatsoever. GIIGNL and all of its members recommend that any entity considering the use of this document first consult with such entity’s legal counsel. This document does not contain any offer, any solicitation of an offer, or any intention to offer or solicit an offer by any member of GIIGNL. No GIIGNL member is required to enter into an agreement based on this document. Page 2 of 29 GIIGNL LNGVOY 16 May 2012 Table of Contents PART I 5 A. VESSEL DESCRIPTION 5 B. DELIVERY OF VESSEL WITHIN THE LAYCAN 5 C. LOADING PORT 6 D. DISCHARGING PORT 6 E. CARGO 7 F. TANKS' CONDITION 7 G. LNG COMPENSATION 8 H. FREIGHT 8 I. BILLING 8 J. LAYTIME 9 K. DEMURRAGE 9 L. CARGO MEASUREMENT 9 M. BOIL-OFF 9 N. LOADING AND UNLOADING RATES 10 PART II 12 1. DESCRIPTION AND CONDITION OF VESSEL 12 2. WARRANTY - VOYAGE – CARGO 15 3. NOTICE OF READINESS AND LAYTIME 16 4. DEMURRAGE 16 5. SAFE BERTHING – SHIFTING 17 6. LOADING AND DISCHARGING 17 7. MARINE SURVEYOR 18 8. DUES AND OTHER CHARGES 18 9. CARGOES EXCLUDED 18 10. -

New Zealand1

Abusive and Offensive Communications: the criminal law of New Zealand1 INTRODUCTION 1.1 This paper details the myriad criminal laws New Zealand has in place to deal with abusive and offensive communication. These range from old laws, such as blasphemy and incitement, to recent laws enacted specifically to deal with online communications. It will be apparent that, unfortunately, New Zealand’s criminal laws now support different approaches to online and offline speech. SPECIFIC LIABILITY FOR ONLINE COMMUNICATION: THE HARMFUL DIGITAL COMMUNICATIONS ACT 2015 The statutory regime 1.2 The most recent government response to abusive and offensive speech is the Harmful Digital Communications Act, which was passed in 2015. The Act was a response to cyberbullying, and based on a report by the New Zealand Law Commission which found that one in ten New Zealand internet users have experienced harmful communications on the internet.2 It contains a criminal offence and a civil complaints regime administered by an approved agency, Netsafe. The Agency focusses on mediating the complaint and seeking voluntary take-down if appropriate, but has no powers to make orders. If the complaint cannot be resolved at this level, the complainant may take the matter to the District Court.3 Although the Act has both criminal and civil components, they are both described below in order to capture the comprehensiveness of the approach to online publication of harmful material. 1.3 The regime is based on a set of Digital Communication Principles, which are: Principle 1 A digital communication should not disclose sensitive personal facts about an individual. -

Vania Is Especi

THE PUNISHMENT OF CRIME IN PROVINCIAL PENNSYLVANIA HE history of the punishment of crime in provincial Pennsyl- vania is especially interesting, not only as one aspect of the Tbroad problem of the transference of English institutions to America, a phase of our development which for a time has achieved a somewhat dimmed significance in a nationalistic enthusiasm to find the conditioning influence of our development in that confusion and lawlessness of our own frontier, but also because of the influence of the Quakers in the development df our law. While the general pat- tern of the criminal law transferred from England to Pennsylvania did not differ from that of the other colonies, in that the law and the courts they evolved to administer the law, like the form of their cur- rency, their methods of farming, the games they played, were part of their English cultural heritage, the Quakers did arrive in the new land with a new concept of the end of the criminal law, and proceeded immediately to give force to this concept by statutory enactment.1 The result may be stated simply. At a time when the philosophy of Hobbes justified any punishment, however harsh, provided it effec- tively deterred the occurrence of a crime,2 when commentators on 1 Actually the Quakers voiced some of their views on punishment before leaving for America in the Laws agreed upon in England, wherein it was provided that all pleadings and process should be short and in English; that prisons should be workhouses and free; that felons unable to make satisfaction should become bond-men and work off the penalty; that certain offences should be published with double satisfaction; that estates of capital offenders should be forfeited, one part to go to the next of kin of the victim and one part to the next of kin of the criminal; and that certain offences of a religious and moral nature should be severely punished. -

Criminal Law: Conspiracy to Defraud

CRIMINAL LAW: CONSPIRACY TO DEFRAUD LAW COMMISSION LAW COM No 228 The Law Commission (LAW COM. No. 228) CRIMINAL LAW: CONSPIRACY TO DEFRAUD Item 5 of the Fourth Programme of Law Reform: Criminal Law Laid before Parliament bj the Lord High Chancellor pursuant to sc :tion 3(2) of the Law Commissions Act 1965 Ordered by The House of Commons to be printed 6 December 1994 LONDON: 11 HMSO E10.85 net The Law Commission was set up by section 1 of the Law Commissions Act 1965 for the purpose of promoting the reform of the law. The Commissioners are: The Honourable Mr Justice Brooke, Chairman Professor Andrew Burrows Miss Diana Faber Mr Charles Harpum Mr Stephen Silber QC The Secretary of the Law Commission is Mr Michael Sayers and its offices are at Conquest House, 37-38 John Street, Theobalds Road, London, WClN 2BQ. 11 LAW COMMISSION CRIMINAL LAW: CONSPIRACY TO DEFRAUD CONTENTS Paragraph Page PART I: INTRODUCTION 1.1 1 A. Background to the report 1. Our work on conspiracy generally 1.2 1 2. Restrictions on charging conspiracy to defraud following the Criminal Law Act 1977 1.8 3 3. The Roskill Report 1.10 4 4. The statutory reversal of Ayres 1.11 4 5. Law Commission Working Paper No 104 1.12 5 6. Developments in the law after publication of Working Paper No 104 1.13 6 7. Our subsequent work on the project 1.14 6 B. A general review of dishonesty offences 1.16 7 C. Summary of our conclusions 1.20 9 D. -

Dr Stephen Copp and Alison Cronin, 'The Failure of Criminal Law To

Dr Stephen Copp and Alison Cronin, ‘The Failure of Criminal Law to Control the Use of Off Balance Sheet Finance During the Banking Crisis’ (2015) 36 The Company Lawyer, Issue 4, 99, reproduced with permission of Thomson Reuters (Professional) UK Ltd. This extract is taken from the author’s original manuscript and has not been edited. The definitive, published, version of record is available here: http://login.westlaw.co.uk/maf/wluk/app/document?&srguid=i0ad8289e0000014eca3cbb3f02 6cd4c4&docguid=I83C7BE20C70F11E48380F725F1B325FB&hitguid=I83C7BE20C70F11 E48380F725F1B325FB&rank=1&spos=1&epos=1&td=25&crumb- action=append&context=6&resolvein=true THE FAILURE OF CRIMINAL LAW TO CONTROL THE USE OF OFF BALANCE SHEET FINANCE DURING THE BANKING CRISIS Dr Stephen Copp & Alison Cronin1 30th May 2014 Introduction A fundamental flaw at the heart of the corporate structure is the scope for fraud based on the provision of misinformation to investors, actual or potential. The scope for fraud arises because the separation of ownership and control in the company facilitates asymmetric information2 in two key circumstances: when a company seeks to raise capital from outside investors and when a company provides information to its owners for stewardship purposes.3 Corporate misinformation, such as the use of off balance sheet finance (OBSF), can distort the allocation of investment funding so that money gets attracted into less well performing enterprises (which may be highly geared and more risky, enhancing the risk of multiple failures). Insofar as it creates a market for lemons it risks damaging confidence in the stock markets themselves since the essence of a market for lemons is that bad drives out good from the market, since sellers of the good have less incentive to sell than sellers of the bad.4 The neo-classical model of perfect competition assumes that there will be perfect information. -

Criminal Code 2003.Pmd 273 11/27/2004, 12:35 PM 274 No

273 No. 9 ] Criminal Code [2004. SAINT LUCIA ______ No. 9 of 2004 ARRANGEMENT OF SECTIONS CHAPTER ONE General Provisions PART I PRELIMINARY Section 1. Short title 2. Commencement 3. Application of Code 4. General construction of Code 5. Common law procedure to apply where necessary 6. Interpretation PART II JUSTIFICATIONS AND EXCUSES 7. Claim of right 8. Consent by deceit or duress void 9. Consent void by incapacity 10. Consent by mistake of fact 11. Consent by exercise of undue authority 12. Consent by person in authority not given in good faith 13. Exercise of authority 14. Explanation of authority 15. Invalid consent not prejudicial 16. Extent of justification 17. Consent to fight cannot justify harm 18. Consent to killing unjustifiable 19. Consent to harm or wound 20. Medical or surgical treatment must be proper 21. Medical or surgical or other force to minors or others in custody 22. Use of force, where person unable to consent 23. Revocation annuls consent 24. Ignorance or mistake of fact criminal code 2003.pmd 273 11/27/2004, 12:35 PM 274 No. 9 ] Criminal Code [2004. 25. Ignorance of law no excuse 26. Age of criminal responsibility 27. Presumption of mental disorder 28. Intoxication, when an excuse 29. Aider may justify same force as person aided 30. Arrest with or without process for crime 31. Arrest, etc., other than for indictable offence 32. Bona fide assistant and correctional officer 33. Bona fide execution of defective warrant or process 34. Reasonable use of force in self-defence 35. Defence of property, possession of right 36. -

Understanding the Five Fundamental Marine Insurance Exclusions

UNDERSTANDING THE FIVE FUNDAMENTAL MARINE INSURANCE EXCLUSIONS June 17, 2016 W. Harry Thurlow and Richard W. Norman COX & PALMER 1 INTRODUCTION The long and well-litigated history of marine insurance has led to a highly developed and codified law relating to marine insurance contracts. Of particular interest to those who underwrite risks and investigate losses in Canada are the marine insurance exclusions set out in the Marine Insurance Act, SC 1993, c 22 (the “MIA”). The MIA’s provisions have been the subject of substantial commentary and interpretation by Canadian courts. This paper will discuss several of these statutory exclusions as well as an additional exclusion which arose in response to the widespread use of Inchmaree cover. While there are many more exclusions which are common to most marine insurance policies, a good understanding of the five fundamental exclusions reviewed below (referred to collectively herein as the “core exclusions”) is key to analyzing basic coverage provisions and in particular, the requirement that perils be fortuitous. MARINE INSURANCE ACT Unless a marine insurance contract provides otherwise, the MIA imposes several exclusions. These are set out in section 53 of the Act, which begins by stating that an insurer is only liable for a loss that is proximately caused by a peril insured against, e.g. a peril of the sea. The Act defines perils of the seas as “…fortuitous accidents or casualties of the seas, but does not include ordinary action of the wind and waves”1. The MIA describes the following major exclusions which are incorporated into Canadian policies: 53. -

Incest Statutes

Statutory Compilation Regarding Incest Statutes March 2013 Scope This document is a comprehensive compilation of incest statutes from U.S. state, territorial, and the federal jurisdictions. It is up-to-date as of March 2013. For further assistance, consult the National District Attorneys Association’s National Center for Prosecution of Child Abuse at 703.549.9222, or via the free online prosecution assistance service http://www.ndaa.org/ta_form.php. *The statutes in this compilation are current as of March 2013. Please be advised that these statutes are subject to change in forthcoming legislation and Shepardizing is recommended. 1 National Center for Prosecution of Child Abuse National District Attorneys Association Table of Contents ALABAMA .................................................................................................................................................................. 8 ALA. CODE § 13A-13-3 (2013). INCEST .................................................................................................................... 8 ALA. CODE § 30-1-3 (2013). LEGITIMACY OF ISSUE OF INCESTUOUS MARRIAGES ...................................................... 8 ALASKA ...................................................................................................................................................................... 8 ALASKA STAT. § 11.41.450 (2013). INCEST .............................................................................................................. 8 ALASKA R. EVID. RULE 505 (2013) -

Criminal Code

Criminal Code Warning: this is not an official translation. Under all circumstances the original text in Dutch language of the Criminal Code (Wetboek van Strafrecht) prevails. The State accepts no liability for damage of any kind resulting from the use of this translation. Criminal Code (Text valid on: 01-10-2012) Act of 3 March 1881 We WILLEM III, by the grace of God, King of the Netherlands, Prince of Orange-Nassau, Grand Duke of Luxemburg etc. etc. etc. Greetings to all who shall see or hear these presents! Be it known: Whereas We have considered that it is necessary to enact a new Criminal Code; We therefore, having heard the Council of State, and in consultation with the States General, have approved and decreed as We hereby approve and decree, to establish the following provisions which shall constitute the Criminal Code: Book One. General Provisions Part I. Scope of Application of Criminal Law Section 1 1. No act or omission which did not constitute a criminal offence under the law at the time of its commission shall be punishable by law. 2. Where the statutory provisions in force at the time when the criminal offence was committed are later amended, the provisions most favourable to the suspect or the defendant shall apply. Section 2 The criminal law of the Netherlands shall apply to any person who commits a criminal offence in the Netherlands. Section 3 The criminal law of the Netherlands shall apply to any person who commits a criminal offence on board a Dutch vessel or aircraft outside the territory of the Netherlands.