Orchestration and Arrangement Level HE5 - 60 CATS

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Introduction to Music Theory

Introduction to Music Theory This pdf is a good starting point for those who are unfamiliar with some of the key concepts of music theory. Reading musical notation Musical notation (also called a score) is a visual representation of the pitched notes heard in a piece of music represented by dots over a set of horizontal staves. In the top example the symbol to the left of the notes is called a treble clef and in the bottom example is called a bass clef. People often like to use a mnemonic to help remember the order of notes on each clef, here is an example. Intervals An interval is the difference in pitch between two notes as defined by the distance between the two notes. The easiest way to visualise this distance is by thinking of the notes on a piano keyboard. For example, on a C major scale, the interval from C to E is a 3rd and the interval from C to G is a 5th. Click here for some more interval examples. It is also common for an increase by one interval to be called a halfstep, or semitone, and an increase by two intervals to be called a whole step, or tone. Joe ReesJones, University of York, Department of Electronics 19/08/2016 Major and minor scales A scale is a set of notes from which melodies and harmonies are constructed. There are two main subgroups of scales: Major and minor. The type of scale is dependant on the intervals between the notes: Major scale Tone, Tone, Semitone, Tone, Tone, Tone, Semitone Minor scale Tone, Semitone, Tone, Tone, Semitone, Tone, Tone For example (by visualising a keyboard) the notes in C Major are: CDEFGAB, and C Minor are: CDE♭FGA♭B♭. -

Sampling and Remixes

DE FR EN SEARCH Sampling and Remixes The articles about arrangements in the “Good to know” series have so far focused on “conventional” arrangements of musical works. Sampling and remixes are two additional and specic forms of arrangement. What rights need to be secured when existing recordings are used to produce a new work? What agreements have to be contracted? Text by Claudia Kempf and Michael Wohlgemuth From the copyright point of view, remixes and sampling are specic forms of arrangement. (Photo: Tabea Hüberli) Sound samplings come in many dierent forms and techniques. But they all have one thing in common: they incorporate parts of a musical recording into a new work. This regularly raises the question whether such parts of works or samples are protected by copyright or – especially in the case of very short sound sequences – whether they may be used freely. In the case of a remix, an existing production is taken and re-arranged and re-mixed. This may involve taking apart a whole work and putting it together again with the addition of new elements. Theoretically, the degree of re-arrangement in a remix may range from a simple cover version to a completely new arrangement. As a rule, a remix is simply an arrangement. Remixes generally keep a work’s existing title and add a tag which refers either to the form of use (radio edit / extended club version, or similar) or the name of the remixer (generally a well-known DJ). By contrast with conventional arrangements, in addition to using an existing work to create a derived work or arrangement, samples and remixes also use an existing sound recording. -

Glossary for Music the Glossary for Music Includes Terms Commonly Found in Music Education and for Performance Techniques

Glossary for Music The glossary for Music includes terms commonly found in music education and for performance techniques. The intent of the glossary is to promote consistent terminology when creating curriculum and assessment documents as well as communicating with stakeholders. Ability: natural aptitude in specific skills and processes; what the student is apt to do, without formal instruction. Analog tools: category of musical instruments and tools that are non-digital (i.e., do not transfer sound in or convert sound into binary code), such as acoustic instruments, microphones, monitors, and speakers. Analyze: examine in detail the structure and context of the music. Arrangement: setting or adaptation of an existing musical composition Arranger: person who creates alternative settings or adaptations of existing music. Articulation: characteristic way in which musical tones are connected, separated, or accented; types of articulation include legato (smooth, connected tones) and staccato (short, detached tones). Artistic literacy: knowledge and understanding required to participate authentically in the arts Atonality: music in which no tonic or key center is apparent. Artistic Processes: Organizational principles of the 2014 National Core Standards for the Arts: Creating, Performing, Responding, and Connecting. Audiate: hear and comprehend sounds in one’s head (inner hearing), even when no sound is present. Audience etiquette: social behavior observed by those attending musical performances and which can vary depending upon the type of music performed. Benchmark: pre-established definition of an achievement level, designed to help measure student progress toward a goal or standard, expressed either in writing or as an example of scored student work (aka, anchor set). -

Studies in Instrumentation and Orchestration and in the Recontextualisation of Diatonic Pitch Materials (Portfolio of Compositions)

Studies in Instrumentation and Orchestration and in the Recontextualisation of Diatonic Pitch Materials (Portfolio of Compositions) by Chris Paul Harman Submitted to The University of Birmingham for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Department of Music School of Humanities The University of Birmingham September 2011 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. Abstract: The present document examines eight musical works for various instruments and ensembles, composed between 2007 and 2011. Brief summaries of each work’s program are followed by discussions of instrumentation and orchestration, and analysis of pitch organization. Discussions of instrumentation and orchestration explore the composer’s approach to diversification of instrumental ensembles by the inclusion of non-orchestral instruments, and redefinition of traditional hierarchies among instruments in a standard ensemble or orchestral setting. Analyses of pitch organization detail various ways in which the composer renders diatonic -

Album Hunter Mp3 Download Album Hunter Mp3 Download

album hunter mp3 download Album hunter mp3 download. A fan-arrangement album celebrating the music and franchises from Super Smash Bros , featuring musicians from around the world. Harmony of Heroes is a Super Smash Bros fan-arrangement album celebrating and paying tribute to the music of Super Smash Bros, Super Smash Bros. Melee and Super Smash Bros. Brawl. It is a collaborative effort made up of musicians on a global scale, ranging from digitally synthesised music to live performances covering a variety of different genres. The diversity of the album allows us to reach out to many different types of fans no matter their musical preference. The album builds upon the success of Harmony of a Hunter and Harmony of a Hunter: 101% Run, two Metroid focused albums marking the 25 th Anniversary of the Metroid franchise. Both of these albums covered the majority of music present in Metroid games at that time, and Smash Bros felt like the next natural step in an effort to reach out to even more people. The name Heroes was chosen to describe the characters we choose in Super Smash Bros, the ones who help us reign triumphant in those epic brawls. They are our heroes. Our album is vast in content, covering the majority of franchises featured in these titles. While you can expect to hear iconic themes representing some of the game’s most notable additions, you may be surprised to find we have covered some of the more obscure ones too. In some cases, we haven’t been afraid to experiment a little, offering a fresh perspective to those who listen. -

How to Effectively Listen and Enjoy a Classical Music Concert

HOW TO EFFECTIVELY LISTEN AND ENJOY A CLASSICAL MUSIC CONCERT 1. INTRODUCTION Hearing live music is one of the most pleasurable experiences available to human beings. The music sounds great, it feels great, and you get to watch the musicians as they create it. No matter what kind of music you love, try listening to it live. This guide focuses on classical music, a tradition that originated before recordings, radio, and the Internet, back when all music was live music. In those days live human beings performed for other live human beings, with everybody together in the same room. When heard in this way, classical music can have a special excitement. Hearing classical music in a concert can leave you feeling refreshed and energized. It can be fun. It can be romantic. It can be spiritual. It can also scare you to death. Classical music concerts can seem like snobby affairs full of foreign terminology and peculiar behavior. It can be hard to understand what’s going on. It can be hard to know how to act. Not to worry. Concerts are no weirder than any other pastime, and the rules of behavior are much simpler and easier to understand than, say, the stock market, football, or system software upgrades. If you haven’t been to a live concert before, or if you’ve been baffled by concerts, this guide will explain the rigmarole so you can relax and enjoy the music. 2. THE LISTENER'S JOB DESCRIPTION Classical music concerts can seem intimidating. It seems like you have to know a lot. -

Beethoven's Fourth Symphony: Comparative Analysis of Recorded Performances, Pp

BEETHOVEN’S FOURTH SYMPHONY: RECEPTION, AESTHETICS, PERFORMANCE HISTORY A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School Of Cornell University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Mark Christopher Ferraguto August 2012 © 2012 Mark Christopher Ferraguto BEETHOVEN’S FOURTH SYMPHONY: RECEPTION, AESTHETICS, PERFORMANCE HISTORY Mark Christopher Ferraguto, PhD Cornell University 2012 Despite its established place in the orchestral repertory, Beethoven’s Symphony No. 4 in B-flat, op. 60, has long challenged critics. Lacking titles and other extramusical signifiers, it posed a problem for nineteenth-century critics espousing programmatic modes of analysis; more recently, its aesthetic has been viewed as incongruent with that of the “heroic style,” the paradigm most strongly associated with Beethoven’s voice as a composer. Applying various methodologies, this study argues for a more complex view of the symphony’s aesthetic and cultural significance. Chapter I surveys the reception of the Fourth from its premiere to the present day, arguing that the symphony’s modern reputation emerged as a result of later nineteenth-century readings and misreadings. While the Fourth had a profound impact on Schumann, Berlioz, and Mendelssohn, it elicited more conflicted responses—including aporia and disavowal—from critics ranging from A. B. Marx to J. W. N. Sullivan and beyond. Recent scholarship on previously neglected works and genres has opened up new perspectives on Beethoven’s music, allowing for a fresh appreciation of the Fourth. Haydn’s legacy in 1805–6 provides the background for Chapter II, a study of Beethoven’s engagement with the Haydn–Mozart tradition. -

The Classical Period (1720-1815), Music: 5635.793

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 096 203 SO 007 735 AUTHOR Pearl, Jesse; Carter, Raymond TITLE Music Listening--The Classical Period (1720-1815), Music: 5635.793. INSTITUTION Dade County Public Schools, Miami, Fla. PUB DATE 72 NOTE 42p.; An Authorized Course of Instruction for the Quinmester Program; SO 007 734-737 are related documents PS PRICE MP-$0.75 HC-$1.85 PLUS POSTAGE DESCRIPTORS *Aesthetic Education; Course Content; Course Objectives; Curriculum Guides; *Listening Habits; *Music Appreciation; *Music Education; Mucic Techniques; Opera; Secondary Grades; Teaching Techniques; *Vocal Music IDENTIFIERS Classical Period; Instrumental Music; *Quinmester Program ABSTRACT This 9-week, Quinmester course of study is designed to teach the principal types of vocal, instrumental, and operatic compositions of the classical period through listening to the styles of different composers and acquiring recognition of their works, as well as through developing fastidious listening habits. The course is intended for those interested in music history or those who have participated in the performing arts. Course objectives in listening and musicianship are listed. Course content is delineated for use by the instructor according to historical background, musical characteristics, instrumental music, 18th century opera, and contributions of the great masters of the period. Seven units are provided with suggested music for class singing. resources for student and teacher, and suggestions for assessment. (JH) US DEPARTMENT OP HEALTH EDUCATION I MIME NATIONAL INSTITUTE -

How Understanding Arrangement Techniques Can Improve Your Songs Mike Levine on Jul 04, 2017 in Music Theory & Education 1 Comments

Arranging for Success - How Understanding Arrangement Techniques Can I : Ask.Au... Page 1 of 6 Arranging for Success - How Understanding Arrangement Techniques Can Improve Your Songs Mike Levine on Jul 04, 2017 in Music Theory & Education 1 comments Understanding some key universal concepts around arrangement, dynamics and composition can help you take your tracks to the next level. Here's how. Whether you’re in the studio or on stage, just having a strong song and performing it well is not enough. You also need a smart arrangement in order for your song to have its maximum impact. Giving your arrangement a dramatic arc helps make it more interesting and accessible to listeners. It's beyond the scope of this article to focus on specific instruments and how to arrange them for particular musical genres—that would require a series of books—but the aim here is to cover some global arranging concepts, which will apply no matter what the specific style or instrumentation. Contrast is King Just like a painting, a song arrangement needs contrast. If everything is too similar, it will be boring and the listeners will tune out. You want to keep their attention, so you should structure the song so that it’s not static. Think of it almost like a book or play, which has a beginning a middle and an end. You have a number of tools at your disposal for creating drama and interest with your arrangement, which include varying the dynamics, adding to the instrumentation as you go, and building the complexity of the instrument and vocal parts as the song progresses. -

Score-Reading Orchestrationonline.Com

course notes Score-Reading orchestrationonline.com © 2014 Thomas Goss 1 course notes Score-Reading orchestrationonline.com Part 1: Your Visual Ear Score-Reading Course Notes I. What is a Score? compiled by Thomas Goss and Lawrence Spector a. a document which contains an artistic work, free from its creator b. a set of directions for the conductor and musicians c. a visual record of an auditory experience from the imagination of the composer INTRO TO THE SCORE-READING COURSE The purpose of this series is to bring the two experiences of hearing music and seeing notes very close This course is intended as an introduction to score-reading for developing musicians at the orchestral level: composers, arrangers, and conductors in training. As stated in the video, score-reading should be together. A very experienced composer or conductor will observe a page of music and know exactly a lifelong habit. The experienced score-reader will eventually be able to develop the ability of determining what it’s supposed to sound like. This is called “mental hearing,” and can be developed through years of which score, for them, is a timeless artistic statement by whether that score always has new things to scoring and score-reading (and conducting as well). say to their eye and inner ear. II. Musical Literacy a. imagine learning to read music with time spent comparable to learning to read text Table of Contents b. my definition of musical literacy: the ability to read the score of the great works (in addition to knowing styles and eras of music, performers, repertoire, etc.) Part 1: Your Visual Ear ..............................................................................2 c. -

Introduction to Music Technology

PUBLIC SCHOOLS OF EDISON TOWNSHIP DIVISION OF CURRICULUM AND INSTRUCTION INTRODUCTION TO MUSIC TECHNOLOGY Length of Course: Semester (Full Year) Elective / Required: Elective Schools: High Schools Student Eligibility: Grade 9-12 Credit Value: 5 credits Date Approved: September 24, 2012 Introduction to Music Technology TABLE OF CONTENTS Statement of Purpose ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 3 Introduction ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 4 Course Objectives ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 6 Unit 1: Introduction to Music Technology Course and Lab ------------------------------------9 Unit 2: Legal and Ethical Issues In Digital Music -----------------------------------------------11 Unit 3: Basic Projects: Mash-ups and Podcasts ------------------------------------------------13 Unit 4: The Science of Sound & Sound Transmission ----------------------------------------14 Unit 5: Sound Reproduction – From Edison to MP3 ------------------------------------------16 Unit 6: Electronic Composition – Tools For The Musician -----------------------------------18 Unit 7: Pro Tools ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------20 Unit 8: Matching Sight to Sound: Video & Film -------------------------------------------------22 APPENDICES A Performance Assessments B Course Texts and Supplemental Materials C Technology/Website References D Arts -

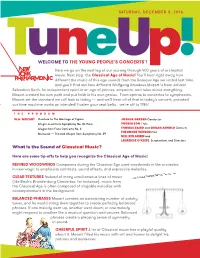

What Is the Sound of Classical Music? WELCOME to THE

Life on Tour in the Classical Age of Music During the 18th century it was fashionable for wealthy young men to finish their education with a grand tour of Europe’s SATURDAY, DECEMBER 3, 2016 cultural capitals. Exposure to art, languages, and artifacts developed young minds and their knowledge of the world. Mozart was just 7 years old when he set off on his first grand tour with his parents and sister, designed as an opportunity to showcase young Wolfgang and sister Nannerl’s talents. What might it be like to go on tour in the 1760s? TRAVEL CHALLENGES The Mozart family traveled about 2,500 miles — In addition to carriage breakdowns, which meant delays for the distance from New York to Los Angeles — in a days while repairs were being made, the cold chill during the cramped, unheated, incredibly bumpy carriage. rides led to lots of illness. Rheumatic fever, tonsillitis, scarlet TM Travels by boat across rivers and the sea were fever, and typhoid fever were experienced by Mozart family WELCOME TO THE YOUNG PEOPLE’S CONCERTS ! equally unpleasant! members, who were bedridden for weeks at a time. TuneUp! Here we go on the next leg of our journey through 400 years of orchestral LODGING HIGHLIGHTS music. Next stop: the Classical Age of Music! You’ll hear right away how The family stayed everywhere from a cramped Wolfgang and Nannerl performed for some of Europe’s most different the music of this age sounds from the Baroque Age we visited last time. three-room apartment above a barber shop to distinguished royalty and at some of the world’s loveliest Buckingham palace! palaces.