Duluth-Food-Access.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Central Entrance

central Community Advisory entranceDULUTH, MN Committee Charter Overview The Central Entrance Community Advisory Committee (CAC) is established to provide advice to the Steering Committee during development of a vision and concepts for rebuilding Central Entrance from Mesaba Avenue to Trinity Road. Purpose The purpose of the CAC is to serve as a voice for the community and provide lived experiences and expertise, as individuals who frequently travel along Central Entrance. 1. Provide input on past study recommendations to carry forward or to set aside. 2. Provide input on the needs and issues for all travel modes. 3. Provide input on vision and goals. 4. Review and comment on design concepts. 5. Communicate study and study information to greater corridor communities and organizations members represent. Committee Member Responsibilities Each member of the CAC agrees to: 1. Attend as many of the meetings identified below as able and to participate in discussions by sharing ideas and expertise. 2. Be a voice to advance the broader interests of the community. 3. Routinely report back to their organization or community with study details and updates. 4. Listen to and respect the viewpoints of other CAC members. Membership Membership is intended to represent the diversity of interests and stakeholders that use Central Entrance. The following organizations have been invited to appoint members • Duluth City Council (Ward 3, Ward 4, At-large members) • St. Louis County District 1 • Duluth Transit Authority • We Walk in Duluth • Duluth Heights Community Club • Central Hillside Community Club • Metropolitan Interstate Council Bicycle Pedestrian Advisory Committee • Duluth Area Chamber of Commerce • Miller Hill Mall • Metropolitan Interstate Council • Additional members as needed to ensure representation central Community Advisory entranceDULUTH, MN Committee Charter Meetings Three CAC meetings are anticipated and CAC members are encouraged to attend two public virtual workshops. -

Food Resources in Duluth During COVID-19 Version #4 (7/21/2020) *See Corresponding List Below Sunday Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday Saturday

Food Resources in Duluth During COVID-19 Version #4 (7/21/2020) *See corresponding list below Sunday Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday Saturday Breakfast 5 2 5 13 2 13 2 5 13 2 13 2 5 13 5 5 2 5 7 2 7 9 2 5 7 2 7 9 2 5 7 5 18 13 14 18 Lunch 9 13 14 13 14 18 13 14 18 13 14 Key 18 20 20 Resources for seniors 5 6 14 20 6 14 20 6 7 14 6 7 14 5 7 14 5 Dinner Resources for 20 20 20 youth Resources for all ages Groceries/ 2 3 4 2 3 11 2 3 4 2 3 15 2 3 4 8 11 Delivery/ Resources for 18 12 12 17 8 16 Food 15 18 11 SNAP card Pick-up 19 holders .Organization Description Location Days Hours Phone 1 AgeWell Arrowhead Groceries-To-Go 306 W Superior St Ste 10 Duluth, MN 55802 Weekly Drop off at scheduled time 218-623-7800 Take out meals and food delivery. 2 AEOA Lincoln Park Center - 2014 W 3rd St Duluth MN 55806 218-727-4321 Registration required. Monday - Friday 6:00AM - 1:00PM Boys and Girls Club 3 Food care packages. Can connect 2407 W 4th St. Duluth, MN 55806 Monday - Friday 218-725-7706 of the Northland families with resources 9:00AM - 4:30PM CHUM Emergency First come first serve food pick-up 120 N. 1st Ave West Duluth, MN 55802 Wednesday and Friday 10:00AM - NOON 218-727-2391 4 Food Shelf Every Monday through First come first serve food pick-up 4831 Grand Av Duluth, MN 55807 the end of July 10:00AM - NOON 218-628-0333 Monday, Wednesday, Breakfast: 8:30AM - 9:30AM; 5 Damiano Center - Free hot and bagged meals in the Community Kitchen west parking lot Friday, Saturday, Sunday Lunch: 11:30AM - 1:00PM 218-726-0500 206 W 4th St Duluth, MN 55806 Friday, Saturday, Sunday Dinner: 5:00PM - 6:00PM 6 Damiano Center - Bagged meals served out of Kids’ Kids’ Kitchen Kitchen entrance 2nd Av W side Monday - Thursday 3:00PM - 6:00PM 218-336-1033 *For bus route information to these locations, please call 218-722-7283. -

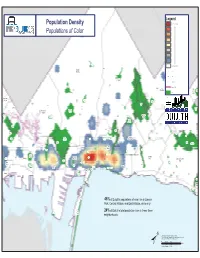

Population Density Populations of Color

Legend Legend Population Density Highest Population Density Populations of Color Sonside Park Lowest Population Density Duluth Heights School Æc Library Kenwood Hospital or Clinic Recreational Trail Rice Lake Park Woodland Athletic Lake Complex Park Annex Pleasant View Park Bayview Duluth Heights Community Heights Recreation Cntr Hartley Field Hartley Park Downer Park Janette Cody Pennel Park Pollay Arlington Park Piedmont Athletic Complex Morley Heights Hts/Parkview Oneota Park Piedmont Hunters Community Recreation Center Park Bagley Nature Area (UMD) Brewer Park Chester Park Bellevue Park Amity Park Amity Creek Park Enger Chester Quarry Municipal Copeland Lakeview Park Community Grant Community Park Golf Course Center Recreation Center Park-UMD Enger Hawk Park Ridge Hawk Ridge Nature Reserve Hilltop Park East Hillside Lincoln Congdon Park Old Park Main Cascade Park Park Portland Wheeler Square Athletic Washington Congdon Complex Central Com Rec Memorial Ctr Community Recreation Center Denfeld Hillside Park Lakeside-Lester Central Park Park Russell Midtown Civic Square Spirit Park Center Point of Rocks Park Valley Wade Sports Point of Complex Rocks Park Manchester Lincoln Square Lake Place Plaza Endion Leif Erickson Rose Garden Park Corner of Park the Lake CBD Park Lakewalk Washington East Square Irving Bayfront Park Oneota Grosvenor Square Lester/Amity Park Canal Park North Shore University Park Kitchi Gammi Park Franklin Park 46% of Duluth's populations of color live in Lincoln Park, Central Hillside, and East Hillside, while only Park 24% of Duluth's total population lives in these three Rice's Point Boat Landing Point neighborhoods. Data Source: Minnesota Population Center. National Historical Geographic Information System: Version 2.0 ± Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota 2011. -

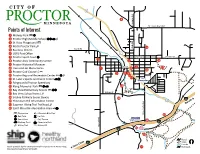

Proctor Recreation

It’s way cooler up the hill There are lots of trains here Proctor: We're just outside of Duluth Where fog is thick as soup Built by resilient, hard-working people C I T Y O F 2 4 the Hoghead is Home is where MINNESOTA St. Louis River Rd Points of Interest 1 Midway Park 2 Proctor High/Middle School e 3 St. Rose Playground v A d 4 North Proctor Park n 2nd Ave2 Ave14 Rd Lavaque Proctor: The city on the hill Proctor: Stark Rd 5 Business District 6 2 USPS Post Office 7 55thth StSt VinlandVinland StSt Proctor Sport Court Li 1 8 Proctor Area Community Center 5 16 � le town with a big heart le town 9 Proctor Historical Museum 2nd2nd StSt 7 10 Train and Jet Monuments 2 6 17 15 11 Proctor Golf Course 3 8 9 12 Proctor Regional Recrea�on Center 10 11 13 St. Luke's Sports and Event Center 14 Fairgrounds/Proctor Speedway 15 Klang Memorial Park 12 16 Bay View Elementary School Kirkus St 17 Bay View School Forest A community built by the railroad the railroad built by A community The city up in the clouds 18 Skyline Parkway Scenic Byway 13 35 19 Thompson Hill Informa�on Center 2 20 Superior Hiking Trail Trailhead Duluth→ 21 Spirit Mountain Recrea�on Area Playground Mountain Bike Trail Boundary Ave 19 Ball Field Ice Rink Sport Court Golf Course 18 Walking Track Adventure Park 35 Hiking Trail Sliding Hill Ugstad Rd Ugstad 35 A city with a town A city with a town Three square miles of can do miles of can square Three 20 Roads 35 Trails Creeks Made possible by the Statewide Health Improvement Partnership, 21 Railroads the hour Minnesota Department -

Comprehensive Operations Analysis Existing Conditions Summary February 2021

Comprehensive Operations Analysis Existing Conditions Summary February 2021 Presented to Duluth Transit Authority Prepared by Connetics Transportation Group 1.0 Introduction In August 2020, the Duluth Transit Authority (DTA) engaged Connetics Transportation Group (CTG) to conduct a Comprehensive Operations Analysis (COA) of their fixed-route transit system. This technical memorandum presents the methodology and findings of the existing conditions analysis for the COA. The COA is structured around five distinct phases, with the existing conditions analysis representing Phase 2 of the process. The following outlines each anticipated phase of the COA with corresponding objectives: Phase 1 Guiding Principles: Determines the elements and strategies that guide the COA process. Phase 2 Existing Conditions: Review and assess the regional markets and existing DTA service. Phase 3 Identify and Evaluate Alternatives: Create service delivery concepts for the future DTA network. Phase 4 Finalize Recommended Network: Select a final recommended network for implementation. Phase 5 Implementation and Scheduling Plan: Create a plan to executive service changes and implement the recommended network. The DTA provides transit service to the Twin Ports region, primarily in and around the cities of Duluth, Minnesota and Superior, Wisconsin. In August 2020, CTG worked with DTA staff and members of a technical advisory group (TAG) to complete Phase 1 of the COA (Guiding Principles). This phase helped inform CTG of the DTA and TAG member expectations for the COA process and desired outcomes of the study. They expect the COA process to result in a network that efficiently deploys resources and receives buy-in from the community. The desired outcomes include a recommended transit network that is attractive to Twin Port’s residents, improves the passenger experience, improves access to opportunity, is equitable, is resilient, and is easy to scale when opportunity arises. -

Guide to the Duluth Area Attractions

Guide to the Duluth Area Attractions Summer 2018 2018 Adventure Zone Family Fun Center 218-740-4000 / www.adventurezoneduluth.com SUMMER HOURS: Memorial Day - Labor Day Sunday - Thursday: 11am – 10pm Friday & Saturday 11am - Midnight WINTER HOURS: Monday – Thursday: 3 – 9pm Friday & Saturday: 11am – Midnight Sunday: 11am – 9pm DESCRIPTION: “Canal Park’s fun and games from A to Z”. There is something for everyone! The Northland’s newest family attraction boasts over 50,000 square feet of fun, featuring multi-level laser tag, batting cages, mini golf, the largest video/redemption arcade in the area, Vertical Endeavors rock climbing walls, virtual sports challenge, a kid’s playground and more! Make us your party headquarters! RATES: Laser Zone: Laser Tag $6 North Shore Nine: Mini Golf $4 Sport Plays: Batting Cages or Virtual Sports Simulator $1.75 per play or 3 plays for $5 DIRECTIONS: Located in Duluth’s Canal Park Business District at 329 Lake Avenue South, just blocks from Downtown Duluth and the famous Aerial Lift Bridge. DEALS: Adventure Zone offers many Daily Deals and Weekly Specials. A sample of those would include the Ultra Adventure Pass for $17, a Jr. Adventure Pass for $11, Monday Fun Day, Ten Buck Tuesday, Thursday Family Night and a Late Night Special on Fri & Sat for $10! AMENITIES: Meeting and Banquet spaces available with catering options from local restaurants. 2018 Bentleyville “Tour of Lights” 218-740-3535 / www.bentleyvilleusa.org WINTER HOURS: November 17 – December 26, 2018 Sunday – Thursday: 5 - 9pm Friday & Saturday: 5 – 10pm DESCRIPTION: A non-profit, charitable organization that holds a free annual family holiday light show – complete with Santa, holiday music and fire pits for roasting marshmallows. -

Comprehensive Operations Analysis Recommended Draft Network Individual Route Summaries June 2021

Comprehensive Operations Analysis Recommended Draft Network Individual Route Summaries June 2021 Presented to Duluth Transit Authority Prepared by Connetics Transportation Group DTA Better Bus Blueprint Recommended Draft Network Individual Route Summaries Recommended Draft Network Route Frequency and Span Summary DTA Better Bus Blueprint Recommended Draft Network Individual Route Summaries Route Replacement Overview Table Previous Route Recommended Draft Network Replacement Route 1 101 Route 2 101, 103 Route 2F Service to Fon du Lac discontinued Route 2X* 103 Route 3 101, 109 Route 3X* 109 Route 4+ 109 Route 5 101, 103, 107, 108 Route 6 101 Route 7 101, 103 Route 7A 101 Route 7X* 103 Route 8 107, 108 Route 9M 108 Route 9MT 107, 108 Route 10 102, 104, 108, 113 Route 10E+ 102, 104, 113, Route 10H 102 Route 11 102, 105 Route 11K 102, 105, 106, 112 Route 11M+ 105, 112 Route 12 106 Route 13 104, 112 Route 14W Service to Observation Hill discontinued Route 15 113 Route 16 110, 111 Route 16X* 110, 111 Route 17+ 110 Route 17B Service to Billings Park discontinued Route 17S 110 Route 18 112 Route 19 114 Route 23 104, 105 Route S1 101, 109 *Peak Period Express services were reallocated into frequency on local services +Sections of this route discontinued. Check specific route changes for more details Routes 101 & 102 denote high frequency (pre-BRT) service DTA Better Bus Blueprint Recommended Draft Network Individual Route Summaries Route 101: Spirit Valley-DTC-UMD Route 101 is one of two, pre-BRT routes that make up the high frequency spine of the Better Bus Blueprint Recommended Draft Network. -

August 22, 2018 the Honorable Steven Mnuchin Secretary

August 22, 2018 The Honorable Steven Mnuchin Secretary U.S. Department of the Treasury 1500 Pennsylvania Avenue, NW Washington, DC 20220 Dear Secretary Mnuchin: The undersigned organizations urge the Treasury Department to issue interim guidance with respect to drafting errors that were made to the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (“Act”) -- provisions dealing with qualified improvement property (“QIP”) and net operating losses (“NOL”). The signatories to this letter may have an interest in one but not necessarily both of the provisions but recognize the need to have them both resolved on an expeditious basis. The delay in correcting these provisions has caused economic hardship for some retailers, restaurants, members of the real estate industry, and suppliers of building products, and is also delaying investments across the economy that impact the communities in which these companies are doing business. This also results in safety concerns because, in some cases, it is causing a delay in upgrading existing sprinkler systems, creating a more perilous situation for our nation’s firefighters. At the outset, it is important to note that it is widely acknowledged that both the QIP and NOL provisions contain unintended drafting errors such that the provisions do not currently operate consistent with Congressional intent – there are no policy or technical objections suggesting that these drafting errors should not be corrected. The drafting error in the QIP provision causes improvements to buildings to be written off over 39 years instead of one year as contemplated under the Act. As a result, a taxpayer gets to write off only 2.5% of their improvement costs in the year the expenditures are made, and 97.5% over the remaining 38 years, instead of writing off 100% of the cost in the year the expenditures are made. -

Duluth's East Downtown, Hillside and Waterfront Charrette Report and Plan

Duluth’s East Downtown, Hillside and Waterfront Charrette Report and Plan A Study Prepared for the City of Duluth, Minnesota Based on the July 2005 Charrette by the Knight Program inCommunity Building, University of Miami School of Architecture 1 Charrette Team and Sponsors University of Miami University of Minnesota Contributors School of Students for the Duluth-Superior Area Architecture Faculty New Urbanism Community Foundation Charles C. Bohl Mike Janicki FI Salter Company Joanna Lombard Mike Lau Mercury Investment Company Elizabeth Plater-Zyberk Minnesota Power Knight Program Consultants North Shore Bank of Commerce Knight Program Staff Architecture, Design, and Coding Andrea Gollin Robert Claybaugh Northland Foundation Kim Pou Peter Harmatuck Carolyn Sundquist Susan Manns Sherman Associates Knight Program Fellows US Bank Tom Cotruvo Peter Musty Jim Epstein Dan Parolek In-kind Lisa Hogan Jeff Schommer A&L Properties Michelle Jones Traffic Engineer American Institute of Architects, Yon Lambert Fred Dock North Minnesota Chapter Jeremy Liu Urban Planning Area Partnership for Andrew Miller and Report Writing Economic Expansion Jessica Cogan Millman Stuart Sirota Arrowhead Regional Dan Parolek Health Industry Development Commission Veronica Rosales Dougal Hewitt Duluth Economic Will Selman Bon Secours Richmond Development Authority Ken Stapleton Health System Duluth Entertainment Kendra Wills Photography Convention Center Charles C. Bohl Duluth Public Arts Commission University of Miami Jim Epstein Greater Downtown Council Suburb and Town Design Holiday Inn Hotel and Suites, Graduate Students Stuart Sirota Alex Adams Sandy Sorlien Downtown Waterfront Alissa Escobar LHB Sponsors Justin Falango North Shore Scenic Railroad City of Duluth Susan Manns On the Limit Duluth News Tribune Juan Mullerat Visit Duluth Knight Program in Community Canan Mutlu Building, University of Miami Joachim Perez School of Architecture Thanks to the John S. -

Feature Advertising by U.S. Supermarkets Meat and Poultry

United States Department of Agriculture Agricultural Feature Advertising by U.S. Supermarkets Marketing Service Meat and Poultry Livestock, Poultry and Seed Program Independence Day 2017 Agricultural Analytics Division Advertised Prices effective through July 04, 2017 Feature Advertising by U.S. Supermarkets During Key Seasonal Marketing Events This report provides a detailed breakdown of supermarket featuring of popular meat and poultry products for the Independence Day marketing period. The Independence Day weekend marks the high watershed of the summer outdoor cooking season and is a significant demand period for a variety of meat cuts for outdoor grilling and entertaining. Advertised sale prices are shown by region, state, and supermarket banner and include brand names, prices, and any special conditions. Contents: Chicken - Regular and value packs of boneless/skinless (b/s) breasts; b/s thighs; split, bone-in breasts; wings; bone-in thighs and drumsticks; tray and bagged leg quarters; IQF breast and tenders; 8-piece fried chicken. Northeast .................................................................................................................................................................. 03 Southeast ................................................................................................................................................................. 21 Midwest ................................................................................................................................................................... -

Consumer Acceptance Study of California Fresh Strawberries

Consumer Acceptance Study of California Fresh Strawberries Summary of Findings March 2011, TransFRESH Corporation © 2011 Chiquita Brands L.L.C TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ............................................................................................................................................ 3 IN-STORE DISPLAY PURCHASE INTENT (SECTION 2.3) ........................................................................................................ 3 CLAMSHELL PURCHASE INTENT (SECTION 2.4) ................................................................................................................. 3 FRUIT QUALITY (SECTION 2.5) ........................................................................................................................................ 3 CONCLUSIONS (SECTION 3.0) ....................................................................................................................................... 3 1.0 GENERAL METHODS ......................................................................................................................................... 4 1.1 MARKETS, AUDIT PERIODS AND AUDITOR SELECTION ................................................................................................. 4 1.2 STORE DISPLAY EVALUATIONS .................................................................................................................................. 4 1.3 CLAMSHELL PURCHASE SELECTION .......................................................................................................................... -

Download Here

City of Duluth PARKS AND GREEN SPACE Amity Park 2940 Seven Bridges Rd Arlington Athletic Complex 601 S Arlington Ave Bardon's Peak Forest 105th Ave W & Skyline Dr Bardon's Peak Blvd Hwy 1 at Knowlton Creek to Becks Rd Bayfront Festival Park 700 Railroad St Birchwood Park 222 W Heard St Blackmer Park 8301 Beverly St Boy Scout Landing 1 Commonwealth Ave Brewer/Bellevue Park 2588 Haines Rd Brighton Beach Park (Kitchi Gammi) 6202 Congdon Blvd Bristol Beach Park Congdon Blvd & Leighton St Buffalo Park St. Marie St & Vermilion Rd Canal Park Canal Park Drive & Morse St Carson Park 1101 131st Ave. W Cascade Park 600 N Cascade St Central Hillside Park 3 E 3rd St Central Park 1515 W 3rd St Chambers Grove Park 100 134th Ave W Chester Park (upper) 1800 E Skyline Parkway Chester Park (lower) 501 N 15th Ave Civic Center 5th Ave W & 1st St Cobb Park 20 Redwing St Como Park (Glen Avon) 2401 Woodland Ave Congdon Boulevard 60th Ave E to Lake Co Line along Shore Congdon Park 3204 Congdon Park Dr Downer Park 3615 Vermillion Rd Duluth Heights Park 33 W Mulberry St Endion Park 1616 E 2nd St Enger Golf Course 1801 W Skyline Blvd Enger Park 1601 Enger Tower Rd Ericson Place 5716 W Skyline Pkwy Fairmont Park 72nd Ave W & Grand 5th Ave Mall Michigan St to 1st St 59th Ave W Park Center Island at 59th Ave W Fond du Lac Park 410 131st Ave W 42nd Ave E Park 42nd Ave E below London Rd Franklin Square (12th St Beach) 1220 S Lake Ave Franklin Tot Lot 1202 Minnesota Ave Gary New Duluth Park 801 101st Ave W Gary New Duluth Dog Park 822 101st Ave W Gasser Park 96th Ave