Place of Safety

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

IMO Report on SSE 6

E SUB-COMMITTEE ON SHIP SYSTEMS AND SSE 6/18 EQUIPMENT 1 April 2019 6th session Original: ENGLISH Agenda item 18 REPORT TO THE MARITIME SAFETY COMMITTEE TABLE OF CONTENTS Section Page 1 GENERAL 4 2 DECISIONS OF OTHER IMO BODIES 4 3 SAFETY OBJECTIVES AND FUNCTIONAL REQUIREMENTS OF THE 5 GUIDELINES ON ALTERNATIVE DESIGN AND ARRANGEMENTS FOR SOLAS CHAPTERS II-1 AND III 4 DEVELOP NEW REQUIREMENTS FOR VENTILATION OF SURVIVAL 8 CRAFT 5 CONSEQUENTIAL WORK RELATED TO THE NEW CODE FOR SHIPS 14 OPERATING IN POLAR WATERS 6 REVIEW SOLAS CHAPTER II-2 AND ASSOCIATED CODES TO 17 MINIMIZE THE INCIDENCE AND CONSEQUENCES OF FIRES ON RO-RO SPACES AND SPECIAL CATEGORY SPACES OF NEW AND EXISTING RO-RO PASSENGER SHIPS 7 AMENDMENTS TO MSC.1/CIRC.1315 22 8 AMENDMENTS TO CHAPTER 9 OF THE FSS CODE FOR FAULT 25 ISOLATION REQUIREMENTS FOR CARGO SHIPS AND PASSENGER SHIP CABIN BALCONIES FITTED WITH INDIVIDUALLY IDENTIFIABLE FIRE DETECTOR SYSTEMS 9 REQUIREMENTS FOR ONBOARD LIFTING APPLIANCES AND 26 ANCHOR HANDLING WINCHES 10 REVISED SOLAS REGULATIONS II-1/13 AND II-1/13-1 AND OTHER 33 RELATED REGULATIONS FOR NEW SHIPS I:\SSE\06\SSE 6-18.docx SSE 6/18 Page 2 Section Page 11 DEVELOPMENT OF GUIDELINES FOR COLD IRONING OF SHIPS AND 33 CONSIDERATION OF AMENDMENTS TO SOLAS CHAPTERS II-1 AND II-2 12 UNIFIED INTERPRETATION OF PROVISIONS OF IMO SAFETY, 35 SECURITY, AND ENVIRONMENT-RELATED CONVENTIONS 13 AMENDMENTS TO PARAGRAPH 4.4.7.6.17 OF THE LSA CODE 43 CONCERNING SINGLE FALL AND HOOK SYSTEMS WITH ON-LOAD RELEASE CAPABILITY 14 REVISION OF THE STANDARDIZED LIFE-SAVING APPLIANCE -

SOLAS Chapter V – 1/7/02

SOLAS Chapter V – 1/7/02 SOLAS CHAPTER V SAFETY OF NAVIGATION The SOLAS (Safety of Life at Sea) Convention is published by the IMO (International Maritime Organisation) at which the ISAF have Consultative Status. SOLAS Chapter V refers to the Safety of Navigation for all vessels at sea. Other Chapters included in the SOLAS Convention are; Chapter I General provisions. Chapter II-1 Construction: subdivision and stability, machinery and electrical installations Chapter II-2 Construction: fire protection, fire detection and fire extinction Chapter III Life saving appliances and arrangements Chapter IV Radio communications Chapter V Safety of Navigation Chapter VI Carriage of grain Chapter VII Carriage of dangerous goods Chapter VIII Nuclear ships Chapter IX Management for the safe operations of ships Chapter X Safety measures for high-speed craft Chapter XI Special measures to enhance maritime safety For the complete SOLAS Convention, please contact IMO at www.imo.org REGULATION 1 - Application 1 Unless expressly provided otherwise, this chapter shall apply to all ships on all voyages, except: .1 warships, naval auxiliaries and other ships owned or operated by a Contracting Government and used only on government non-commercial service; and .2 ships solely navigating the Great Lakes of North America and their connecting and tributary waters as far east as the lower exit of the St. Lambert Lock at Montreal in the Province of Quebec, Canada. However, warships, naval auxiliaries or other ships owned or operated by a Contracting Government and used only on government non-commercial service are encouraged to act in a manner consistent, so far as reasonable and practicable, with this chapter. -

Receiving Afghanistan's Asylum Seekers

FMR 13 19 Receiving Afghanistan’s asylum seekers: Australia, the Tampa ‘Crisis’ and refugee protection by William Maley n 22 January 2002, the announced that the government of the National Party, which made up the Chairman of the government- tiny Pacific nation of Nauru, a state country’s ruling coalition, and the O appointed Council for not party to the 1951 Convention, had opposition Australian Labor Party – Multicultural Australia, Neville Roach, agreed to the processing of asylum and it was left to minor parties, such resigned his position. In a newspaper claims on its soil. Nauru’s agreement as the Australian Democrats and the article three days later, this prominent was secured with a large aid package, Greens, to proffer a more nuanced and highly-respected businessman including payment of the unpaid account of the factors underpinning explained why he had taken such a Australian hospital bills of certain forced migration to Australia. dramatic step, which made headlines Nauruan citizens. Nonetheless, there are a number of right around the country. "If an advis- implications of these events which er", he wrote, "is faced with a Buoyed by the outcome of the Tampa government that has locked itself into Affair and trumpeting the merits of Logo of refugee infor- a position that is completely inflexi- its ‘Pacific solution’ to the problem of mation organisation ble, the opportunity to add value uninvited asylum seekers, the Howard reminding all non- disappears". The asylum seeker con- government was returned to office in indigenous troversy, he went on, "has a general election in November 2001. -

Rescue at Sea, Maritime Interception and Stowaways, November 2006

Selected Reference Materials Rescue at Sea, Maritime Interception and Stowaways November 2006 Introduction Legal issues arising from the involvement of refugees and other persons of concern to UNHCR in maritime incidents such as rescue at sea, maritime interception or stowaway cases, are complex and subject to different areas of international law. Apart from international refugee and human rights laws, maritime obligations, especially, need to be considered. This binder compiles applicable provisions of the international law of the sea, refugee, human rights and criminal law to assist UNHCR colleagues and other interested professionals to better understand the inter-relationship between these different areas of law. The compilation is not comprehensive, only key provisions have been chosen. Since refugee and human rights law provisions have been collected elsewhere, the references included form these areas of law are restricted to existing refoulement prohibitions and a few add provisions, recommendations and guidelines specifically relevant for maritime migration. The binder originally was prepared for a conference on rescue at sea and maritime interception in the Mediterranean. Recommendations adopted by the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe have therefore been included. It also contains background material of relevant conferences convened by UNHCR during the past years. Apart from the reference to the UN Treaty Series, whenever possible, a website link has been added to enable easy access to the complete texts. For most texts, the reference refers to an official UN website. Where this was not possible, another website has been provided. Although such external websites have been carefully chosen, a guarantee about their content and quality cannot be made. -

The Securitization of the “Boat People” in Australia the Case of Tampa

The securitization of the “boat people” in Australia The case of Tampa Phivos Adonis Björn Deliyannis International Relations Dept. of Global Political Studies Bachelor programme – IR103L (IR61-90) 15 credits thesis [Spring / 2020] Supervisor: [Erika Svedberg] Submission Date: 13/08/2020 Phivos Adonis Björn Deliyannis 19920608-2316 Abstract: The thesis will examine how the Australian government through its Prime Minister John Howard presented the asylum seekers on “MV Tampa” ship as a threat jeopardizing Australian security. Using the theory of securitization as a methodological framework and Critical Discourse Analysis as utilized by Fairclough’s Three-dimensional Framework transcripts of interviews by John Howard will be analyzed in order to expose the securitization process that framed the asylum seekers as an existential threat that needed extraordinary measures. Keywords: International Relations, Australia, Immigration, Tampa, Discourse Word count: 13.622 Phivos Adonis Björn Deliyannis 19920608-2316 Table of Contents 1 Introduction …………………………………………………………...…1 2. Literature Review and Theoretical Framework ………......4 2.1 The concept of security and the debate about security studies ……………….....4 2.2 Earlier Research on the securitization of migration ……………………………6 2.3 The Securitization Framework ………………………………………………..8 2.4 Critique ……………………………………………………………………..11 3. Methods …………………………………………………………………12 3.1. Data Selection and Source Criticism ………………………………………...12 3.2. Case Study …………………………………………………………………15 3.3. Critical Discourse Analysis …………………………………………………15 3.4. Methodological Framework: Fairclough’s Three-dimensional framework …….17 4. Analysis ……………………………………………………………….…21 4.1. Background of the “Tampa affair” ……………………………………….…22 4.2. Data Analysis ……………………………………………………………..24 4.3 The Tampa affair – a case of successful securitization……………………….…. 30 5. Conclusion ………………………………………………………….…..31 6. Bibliography …………………………………………………………....32 Phivos Adonis Björn Deliyannis 19920608-2316 Page intentionally left blank Phivos Adonis Björn Deliyannis 19920608-2316 1. -

September 11Th: Has Anything Changed?

13 June 2002 review September 11th: has anything changed? NORWEGIAN REFUGEE COUNCIL Published by the Refugee Studies Centre in association with the Norwegian Refugee Council/Global IDP Project Forced Migration Review from the FMR editors provides a forum for the regular exchange of practical experience, information and elcome to this special issue of FMR ideas between researchers, refugees and internally displaced people, and those who Wwhich has been produced in collabora- work with them. It is published three tion with the Migration Policy Institute, times a year in English, Spanish and Washington DC. We felt that the implica- Arabic by the Refugee Studies tions for refugees and IDPs of the terrorist Centre/University of Oxford in association with the Global IDP Project/Norwegian attacks of 11 September 2001 and the Refugee Council. The Spanish translation, events which followed were so significant Revista de Migraciones Forzadas, that they warranted changing our publishing Corinne Owen is produced by IDEI in Guatemala. schedule to accommodate this additional issue. Editors Many thanks to our MPI colleagues for their work on commissioning and reviewing Marion Couldrey & articles and liaison with authors. Their Introduction (pages 4-7) highlights the context Dr Tim Morris and theses of this issue and presents policy recommendations. Subscriptions Assistant Sharon Ellis Two additional commentaries, which FMR commissioned for its Arabic language edition, have been included, following the MPI special section. These look at the implications of Forced Migration Review Refugee Studies Centre, 11 September for the Middle East and are included for the purpose of further reflection. Queen Elizabeth House, 21 St Giles, Oxford, OX1 3LA, UK We are extremely grateful to the UK Department for International Development (DFID) Email: [email protected] for generously funding the bulk of the cost of producing and distributing the English and Tel: +44 (0)1865 280700 Fax: +44 (0)1865 270721 Arabic language edition of this issue. -

SOLAS 2018 Consolidated Edition

SOLAS 2018 Consolidated Edition CHAPTER I GENERAL PROVISIONS PART A-APPLICATION, DEFINITIONS, ETC. Regulation 1 Application* * Refer to MSC-MEPC.5/Circ.8 on Unified interpretation of the application of regulations governed by the building contract date, the keel laying date and the delivery date for the requirements of the SOLAS and MARPOL Conventions. (a) Unless expressly provided otherwise, the present Regulations apply only to ships engaged on international voyages. (b) The classes of ships to which each Chapter applies are more precisely defined, and the extent of the application is shown, in each Chapter. Regulation 2 Definitions For the purpose of the present regulations, unless expressly provided otherwise: (a) Regulations means the regulations contained in the annex to the present Convention. (b) Administration means the Government of the State whose flag the ship is entitled to fly. (c) Approved means approved by the Administration. (d) International voyage means a voyage from a country to which the present Convention applies to a port outside such country, or conversely. (e) A passenger is every person other than: 1 (i) the master and the members of the crew or other persons employed or engaged in any capacity on board a ship on the business of that ship and (ii) a child under one year of age. (f) A passenger ship is a ship which carries more than twelve passengers. (g) A cargo ship is any ship which is not a passenger ship. (h) A tanker is a cargo ship constructed or adapted for the carriage in bulk of liquid cargoes of an inflammable* nature. -

The Pacific Solution As Australia's Policy

THE 3AC,F,C SOL8TI21 AS A8STRA/,A‘S P2/,CY TOWARDS ASYLUM SEEKER AND IRREGULAR MARITIME ARRIVALS (IMAS) IN THE JOHN HOWARD ERA Hardi Alunaza SD1, Ireng Maulana2 and Adityo Darmawan Sudagung3 1Faculty of Social and Political Sciences, Universitas Tanjungpura Email: [email protected] 2 Political Sciences Iowa State University Email: [email protected] 3International Relations Department Universitas Tanjungpura Email: [email protected] ABSTRACT This research is attempted to answer the question of why John Howard used the Pacific Solution as Australian policy towards Asylum Seekers and Irregular Maritime Arrivals (IMAS). By using the descriptive method with a qualitative approach, the researchers took a specific interest in decision-making theory and sovereignty concept to analyze the phenomena. The policy governing the authority of the Australian Government in the face of the Asylum Seeker by applying multiple strategies to suppress and deter IMAs. The results of this research indicate that John Howard used Pacific Solution with emphasis on three important aspects. First, eliminating migration zone in Australia. Second, building cooperation with third countries in the South Pacific, namely Nauru and Papua New Guinea in shaping the center of IMAs defense. On the other hand, Howard also made some amendments to the Migration Act by reducing the rights of refugees. Immigrants who are seen as a factor of progress and development of the State Australia turned into a new dimension that threatens economic development, security, and socio-cultural. Keywords: Pacific Solution; asylum seeker; Irregular Maritime Arrivals ABSTRAK Tulisan ini disajikan untuk menjawab pertanyaan mengapa John Howard menggunakan The Pacific Solution sebagai kebijakan Australia terhadap Asylum Seeker dan Irregular Maritime Arrivals (IMAs). -

In 1948 an International Conference in Geneva Adopted a Convention Formally Establishing the International Maritime Organization (IMO)

IMO In 1948 an international conference in Geneva adopted a convention formally establishing the International Maritime Organization (IMO). The original name was Inter-Governmental Maritime Consultative Organization, or IMCO, but the name was changed in 1982 to IMO. The IMO Convention entered into force in 1958. IMO is the United Nations specialized agency in charge with the development of a safe, efficient and regulated international shipping industry and the prevention of the marine pollution by ships. The International Maritime Dangerous Goods (IMDG) Code was developed as an international Code for the maritime transport of Dangerous Goods in packaged form, in order to enhance and harmonize the safe carriage of Dangerous Goods and to prevent pollution to the environment. The Code sets out in detail the requirements applicable to each individual substance, material or article, covering matters such as packing, container traffic and stowage, with particular reference to the segregation of incompatible substances. IMDG Code was initially adopted in 1965 as a recommendatory instrument, becoming in 2002 mandatory under SOLAS Convention, from 1 January 2004. It was definitely adopted in Italy with DPR dated June 6th 2005 no. 134, therefore a further Decree for its adoption is not mandatory. Sede legale Piazza Conciliazione n.1, c.a.p. 20123 Milano - Italy Uffici amm.vi e comm.li Via R. Cozzi n.44/46, 20125 Milano – Italy Tel. +39 026431275 - fax +39 0264100319 - [email protected] - www.overpack.it SOLAS The IMO’s Safety of Life at Sea Convention (SOLAS) addresses maritime safety and its most recent update is from 1974. After the terrorist attacks on September 11th 2001, the members of the IMO agreed to develop security measures for ships and ports. -

Contained Maritime Rule Or a Sustainable Solution to the Ever-Controversial Question of Where to Disembark Migrants Rescued at Sea?

The Concept of ‘Place of Safety’: Yet Another Self- Contained Maritime Rule or a Sustainable Solution to the Ever-Controversial Question of Where to Disembark Migrants Rescued at Sea? Martin Ratcovich* I. Introduction The adoption of amendments to the International Convention on Maritime Search and Rescue,1 and the International Convention for the Safety of Life at Sea,2 was a consequence of the well-known Tampa affair.3 The amendments introduced the concept * LLM (Lund), Doctoral Candidate, Faculty of Law, Stockholm University. Martin Ratcovich was a visiting researcher at the ANU College of Law, Australian National University in March–April 2014. He has previously worked at the Ministry of Defence of Sweden and at the Swedish Coast Guard Headquarters. He has also served as Legal Assistant to the Nordic member of the United Nations International Law Commission, ambassador Marie Jacobsson (LLD). The author would like to thank Professor Said Mahmoudi, Stockholm University, for helpful comments. The author would also like to thank Professor Donald R Rothwell and Associate Professors David Letts and Sarah Heathcote, ANU College of Law. Any errors or omissions remain the author’s own. 1 International Convention on Maritime Search and Rescue, opened for signature 1 November 1979, 1405 UNTS 109 (entered into force 22 June 1985) (‘SAR Convention’). 2 International Convention for the Safety of Life at Sea, opened for signature 1 November 1974, 1184 UNTS 278 (entered into force 25 May 1980) (‘SOLAS Convention’). 3 M/V Tampa (‘Tampa’) was a Norwegian container ship that on 26 August 2001 was asked by the Australian Rescue Coordination Centre to assist in the search and rescue operation for an Indonesian ship in the waters between Indonesia and Christmas Island (Australia). -

In the Wake of the Tampa: Conflicting Visions of International Refugee Law in the Management of Refugee Flows

Washington International Law Journal Volume 12 Number 1 Symposium: Australia's Tampa Incident: The Convergence of International and Domestic Refugee and Maritime Law 1-1-2003 In the Wake of the Tampa: Conflicting Visions of International Refugee Law in the Management of Refugee Flows Mary Crock Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.uw.edu/wilj Part of the Comparative and Foreign Law Commons, and the Immigration Law Commons Recommended Citation Mary Crock, In the Wake of the Tampa: Conflicting Visions of International Refugee Law in the Management of Refugee Flows, 12 Pac. Rim L & Pol'y J. 49 (2003). Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.uw.edu/wilj/vol12/iss1/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Reviews and Journals at UW Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Washington International Law Journal by an authorized editor of UW Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Copyright C 2003 Pacific Rim Law & Policy Journal Association IN THE WAKE OF THE TAMPA: CONFLICTING VISIONS OF INTERNATIONAL REFUGEE LAW IN THE MANAGEMENT OF REFUGEE FLOWS Mary Crockt Abstract: The Australian Government's decision in August 2001 to close its doors to a maritime Good Samaritan, Norwegian Captain Rinnan, his crew, and 433 Afghan and Iraqi rescuees, provided a curious contrast to the image of humanity, generosity, and openness that Australia tried so hard to foster during the 2000 Olympic Games in Sydney. Victims or villains according to how the facts and the law are characterized, the MI/V Tampa rescuers represented for lawyers the intersection of a variety of areas of law and a clash of legal principles. -

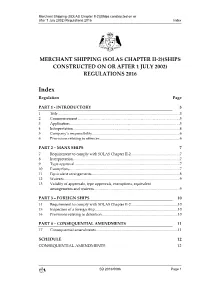

(SOLAS Chapter II-2)(Ships Constructed on Or After 1 July 2002) Regulations 2016 Index

Merchant Shipping (SOLAS Chapter II-2)(Ships constructed on or after 1 July 2002) Regulations 2016 Index c MERCHANT SHIPPING (SOLAS CHAPTER II-2)(SHIPS CONSTRUCTED ON OR AFTER 1 JULY 2002) REGULATIONS 2016 Index Regulation Page PART 1 - INTRODUCTORY 3 1 Title ................................................................................................................................... 3 2 Commencement .............................................................................................................. 3 3 Application ...................................................................................................................... 3 4 Interpretation ................................................................................................................... 4 5 Company’s responsibility .............................................................................................. 6 6 Provisions relating to offences ...................................................................................... 6 PART 2 – MANX SHIPS 7 7 Requirement to comply with SOLAS Chapter II-2 .................................................... 7 8 Interpretation ................................................................................................................... 7 9 Type approval ................................................................................................................. 7 10 Exemptions .....................................................................................................................