Observations of Freeze-Up and Break-Up of the Yukon River At

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tatshenshini River Ten Year Monitoring Report Prepared

Tatshenshini River Ten Year Monitoring Report Prepared for: Yukon Parks Department of Environment Government of Yukon Whitehorse, Yukon Prepared by: Bruce K. Downie PRP Parks: Research & Planning Whitehorse, Yukon Purpose of the Report The Tatshenshini River was designated as a Canadian Heritage River in 2004. The Canadian Heritage River System requires regular monitoring of the natural, heritage and recreational values underpinning each designation. This report presents the results of the ten year review of the river values and key elements of the management strategies for the Yukon portion of the Tatshenshini watershed. The report also points out which characteristics and qualities of the designated river have been maintained as well as the activities and management actions that have been implemented to ensure the continued integrity of the river’s values. And, finally, the report also highlights issues that require further attention in order to maintain the heritage values of the designation. On the basis of these findings, the report assesses the designation status of the Tatshenshini River within the Canadian Heritage River System. Acknowledgements Thanks are due to the those individuals consulted through this analysis and especially to the dedicated individuals in Yukon and First Nations governments who continue to work towards the protection of the natural and cultural values and the wilderness recreational opportunities of the Tatshenshini River. Appreciation is also extended to Parks Canada and the Canadian Heritage Rivers Board Secretariat for their assistance and financial support of this review. All photos provided by: Government of Yukon ____________________________________________________________________________________________________________ PRP Parks: Research & Planning - 2 - March, 2014 Table of Contents Executive Summary ................................................................................................................................................................ -

Final Wild and Scenic River Stu8y N .. + R-E~O--L

Nf s 1-:: ~' { c" ~ 1 - final wild and scenic river stu8y N .. + R-e~o --L october 1982 ALASKA U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE FINAL WILD AND SCENIC RIVER REPORT FOR THE MELOZITNA RIVER, ALASKA Pursuant to Section S(a) of the Wild and Scenic Rivers Act, Public Law 90-542, as amended, the National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior, has prepared a report for the Melozitna Wild and Scenic River Study. This report presents an evaluation and analysis of the Melozitna River and the finding that the river does not meet the criteria of eligibility for inclusion into the National Wild and Scenic Rivers System. A limited number of copies are available upon request to: Regional Director Alaska Regional Office National Park Service 2525 Gambell Street, Room 107 Anchorage, Alaska 99503-2892 (907) 271-4196 TABLE OF CONTENTS Cover Sheet i Summary of Findings and Conclusions 1 Findings 1 Conclusions 1 Introduction 1 Purpose of Study 1 Conduct of Study 2 The Melozitna River Region 2 Location and Topography 2 Climate 4 Land Ownership 4 Land Use 6 Socioeconomic Conditions 6 Population Centers 6 Economy 7 Transportation and Access 7 The Melozitna River Study Area 8 Cultural Resources 8 Fish and Wildlife 9 Geology and Mineral Resources 10 Recreation 12 Scenic Resources 13 Stream Flow Characteristics and Water Quality 14 Water Resource Developments 16 Other Possible Actions 16 Consultation and Coordination of the Draft Report 17 Comments Received 18 Abbreviations ADF&G - Alaska Department of Fish and Game ANILCA - Alaska National Interest Lands Conservation Act BLM - Bureau of Land Management FWS - Fish and Wildlife Service NPS - National Park Service WSR - Wild and Scenic River F. -

TH Best Practices for Heritage Resources

Tr’ondëk Hwëch’in Best Practices for HeritageHeading Resources Place your message here. For maximum impact, use two or three sentences. March 2011 Scope This manual provides the First Nation perspective on working with heritage resources in Tr’ondëk Hwëch’in Traditional Territory. It is not intended as a legal document or to supplant any regulatory frameworks within the Yukon. This is not a comprehensive guide nor is it intended to be static. These best practices represent the best information and resources currently available. The Tr’ondëk Hwëch’in Heritage Department consists of specialists in heritage sites, land-based heritage resources, language, traditional knowledge, and collections management. We are both capable and enthusiastic to work with industry to protect First Nation cultural heritage. It is the role of this department to represent and safeguard the heritage and culture of the Tr’ondëk Hwëch’in. The Tr’ondëk Hwëch’in Heritage Department has proven that working cooperatively with proponents of the mining, development, resource, and industrial sectors is mutually beneficial and assists everyone in meeting their goals. We welcome inquiries from all project proponents. Early collaboration facilitates proper management and protection of our heritage resources. Contact: Tr’ondëk Hwëch’in Heritage Department PO Box 599 Dawson City, Yukon Y0B 1G0 Phone: (867) 993-7113 Fax: (867) 993-6553 Toll-Free: 1-877-993-3400 Cover Photo: Tro’chëk, 2004. 2 Table of Contents Objectives …………………………………………………………………………………………………………..… 4 Legislative Framework ………………………………………………………………………………………… 5 Cultural Context …………………………………………………………………………………………………… 6 Heritage ………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 8 Protecting Heritage Resources …………………………………………………………………………… 10 Reporting …………………………………………………………………………………………………………….… 14 References: Useful Resources, Legislation, Policy, and Best Practices …………… 15 Cut stump recorded during a 2005 heritage Julia Morberg harvesting blueberries. -

A Family Float Trip Down the Yukon River by John Morton

Refuge Notebook • Vol. 10, No. 39 • October 17, 2008 A family float trip down the Yukon River by John Morton the Yukon Quest. But it’s equally challenging when young kids are involved and you’re worried about making sure they’re having fun and are SAFE. This is a tall order when they’re inhaling mosquitoes, pad- dling through water as cold as ice with big hydraulics or camping in bear country. Our “wilderness” trip got a rocky start as we passed a sign below Whitehorse that cautioned about treated effluent being discharged into the river. Sev- eral miles below town we ran into a grocery cart stick- ing out of a muddy bar in a bend on the river. As we paddled across the 30-mile long Lake Lebarge, made famous by Robert Service’s poetic celebration of the Cremation of Sam McGee, we saw abundant signs of humans everywhere: tent sites, rusted cans, old cables, and broken glass. But gradually these modern archaeological arti- facts disappear as we get into dining on grayling and wild onions further down the river. Saxifrage, blue- Straight off the water to the telephone, Mika Morton, 11, bells, cinquefoil, wild sweet pea, and fleabane are flow- reconnects with civilization in Eagle after 700 miles on ering everywhere. Ravens stick their heads into the the Yukon River. Her sister Charly, 6, is not in such a holes of cliff and bank swallows to feed on nestlings rush. The Morton family made the 4-week wilderness and eggs. As we pass one of many spectacular cliffs trip from Whitehorse, Yukon Territory to Eagle, Alaska along the river, a pair of peregrine falcons double by canoe in June. -

Glaciation and the Physical, Chemical and Biological Limnology of Yukon ·Lakes

i i © Minister of Supply and Services Canada 1981 Cat. no. Fs 97-6/966 ISSN 0706-6457 Correct citation for this publication: Lindsey, C. C., K. Patalas, R. A. Bodaly, and C. P. Archibald. 1981. Glaciation and the physical, chemical and biological limnology of Yukon ·lakes. Can. Tech·. Rep. Fish. Aquat Sri. 966: v·i + 37 p. iii I TABLE OF CONTENTS .Iohle. Page g Temperature (temp) (°C) and oxygen (mg/L) profiles for lakes of the ABSTRACT/RESUME v Stewart, Takhini, Tatchun, Teslin, ·and White subdrainages of tile INTRODUCTION . 1 Yukon River drainage system 18 10 Water chemistry of lal~es of the Alsek, SOURCES AND METHODS 1 Liard, Peel, and Porcupine River drainage systems • . 19 RESULTS AND DISCUSSION 11 Water chemistry of lakes of the Atlin, Physical Limnology Lewe~. Mandanna, Nordenskiold, Lake area 2 Pelly;·Big Salmon, and Little Maximum depth 2 Salmon subdrainages of the Yukon Elevation 2 River drainage system 20 Temperature . 2 12 Water chemistry of lakes of the Stewart, Chemical Limnology Takhini, Tatchun, Teslin, and White Total dissolved solids (TDS) 2 subdrainages of the Yukon River Major ions, chlorophyll a, and Secchi 2 drainage system 21 disc visibility • 13 Absolute abundance of crustaceans, Oxygen content . 2 rotifers. and total zooplankton Glaciological Background 2 (crustaceans plus rotifers) and Zooplankton Abundance and Distribution 3 relative abundance (% by number) Glacial History and Fish Distributions 4 of crustacean species for lakes Alsek and White River drainages 4 of the Alsek, Liard, Peel and Por- Yukon River drainages 4 cupine River drainage systems 22 Liard River drainages . 6 14 Absolute abundance of crustaceans, Peel and Porcupine River drainages 6 rotifers, and total zooplankton (crustaceans plus rotifers) and ACKNOWLEDGMENTS 7 relative abundance (% by number) of crustacean species for lakes REFERENCES 8 of the Atlin, Lewes, Mandanna, Nordenskiold, Pelly, Big Salmon, and Little Salmon subdrainages of the Yukon River drainage LIST OF TABLES system . -

Yukon River Basin Study Project Report

YUKON RIVER BASIN STUDY PROJECT REPORT: WILDLIFE NO. 1 FURBEARER INVENTORY, HABITAT ASSESSMENT AND TRAPPER UTILIZATION OF THE YUKON RIVER BASIN B.G. Slough and R.H. Jessup Wildlife Management Branch Yukon Department of Renewable Resources Box 2703 Whitehorse, Yukon Y1A 2C6 January 1984 i This report was funded by the Yukon River Basin Committee (jointly with Yukon Department of Renewable Resources) under the terms of "An Agreement Respecting Studies and Planning of Water Resources in the Yukon River Basin" between Canada, British Columbia and Yukon. The views, conclusions and recommendations are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the Yukon River Basin Committee or the Government of Canada, British Columbia and Yukon. ii ABSTRACT The Yukon Department of Renewable Resources conducted furbearer inventory studies in the Canadian Yukon River Basin in 1982 and 1983. Field studies included beaver (Castor canadensis) food cache and colony site surveys, winter track-count sampling and muskrat (Ondatra zibethica) pushup surveys. Data from the surveys were analyzed in conjunction with ongoing trapper questionnaire and historical fur harvest data sources to characterize furbearer population distributions, levels, trends and habitats. Historical and present fur harvest and trapping activity are described. The fur resource capability and problems and issues associated with impacts on furbearer populations, habitats and user groups are discussed. The populations of wolves Canis lupus, red fox Vulpes fulva, coyote .Q..:.. latrans, red squirre 1 Tamiasciurus hudsonicus, wease 1 Mustela erminea, marten Martes americana, mink Mustela vison, otter Lutra canadensis, wolverine Gulo luscus, beaver, muskrat and lynx Lynx canadensis are all widely distributed within the Yukon River Basin. -

Environmental and Cultural Overview of the Yukon Flats Region Prepared By: Kevin Bailey, USFWS Archaeologist Date: 2/12/2015 In

Environmental and Cultural Overview of the Yukon Flats Region Prepared by: Kevin Bailey, USFWS Archaeologist Date: 2/12/2015 Introduction With a substantial population of Native people residing in their traditional homeland and living a modern traditional lifestyle, the Yukon Flats Refuge and all of the Alaskan Interior is a dynamic and living cultural landscape. The land, people, and wildlife form a tight, interrelated web of relationships extending thousands of years into the past. Natural features and human created “sites” form a landscape of meaning to the modern residents. The places and their meanings are highly relevant to modern residents, not just for people and culture but for the land. To many Gwich’in people culture is not distinct from their homeland. Although only minimally discussed in this overview, this dynamic living cultural landscape should be considered and discussed when writing about this area. Environmental Setting Containing the largest interior basin in Alaska, the Yukon Flats Refuge encompasses over 11 million acres of land in east central Alaska. Extending roughly 220 miles east-west along the Arctic Circle, the refuge lies between the Brooks Range to the north, and the White-Crazy Mountains to the south. The pipeline corridor runs along the refuge’s western boundary while the eastern boundary extends within 30 miles of the Canadian border. The Yukon River bisects the refuge, creating the dominant terrain. As many as 40,000 lakes, ponds, and streams may occur on the refuge, most concentrated in the flood plain along the Yukon and other rivers. Upland terrain, where lakes are less abundant, is the source of important drainage systems. -

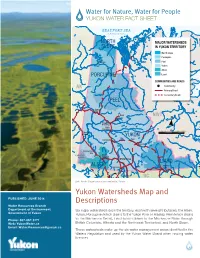

Yukon Watersheds Map and Descriptions

Water for Nature, Water for People YUKON WATER FACT SHEET Left: North Slope tundra and wetlands, Yukon Yukon Watersheds Map and PUBLISHED: JUNE 2014 Descriptions Water Resources Branch Department of Environment Six major watersheds drain the territory, each with several tributaries: the Alsek, Government of Yukon Yukon, Porcupine (which drains to the Yukon River in Alaska), Peel (which drains to the Mackenzie Delta), Liard (which drains to the Mackenzie Basin through Phone: 867-667-3171 Web: YukonWater.ca British Columbia, Alberta and the Northwest Territories), and North Slope. Email: [email protected] These watersheds make up the six water management areas identified in the Waters Regulation and used by the Yukon Water Board when issuing water licences. 1 Water for Nature, Water for People YUKON WATER FACT SHEET City of Whitehorse, and Yukon River Yukon River Basin (including the Alsek River Basin Porcupine River Basin) The Alsek River drains the southwestern portion of the Yukon to the Pacific Ocean. It is classified as a The Yukon River Headwaters contains the Southern Canadian Heritage River because of its significant Lakes region of Yukon and Northern British Columbia; natural resources: massive ice fields, high mountain there are glaciers throughout the mountains of these peaks, unique geologic history, coastal and interior headwaters. The Teslin River joins the Yukon River plant communities, significant grizzly bear population, north of Lake Laberge, contributing water mainly from and diverse bird species. snowmelt runoff in the upper portions of the basin. The Pelly and Stewart Rivers drain the eastern portion of the drainage, including mountainous terrain. -

~L~ICE FORCES on the YUKON RIVER BRIDGE

~ Report No. FHWA-R0-79-82 ?-m 0 U> =-.$ffiiii0 , !!! '°i a:;;,,,,..,...CN ~l~ICE~ ..... FORCES ON THE YUKON RIVER BRIDGE- ~ J978 BREAKUP February 1979 Final Report Document is available to the public through the National Technical Information Service, Springfield, Virginia 22161 OT Prepared for E FEDERAL HIGHWAY ADMINISTRATION 662 ~.J" ? Offices of Research & Development no.FD- Structures • Applied_Mechanics Division 79-82 c.2 Washington, D.C. 20590 FOREWORD This report presents information on FHWA sponsored research on ice forces on highway bridges. The report covers studies relating to the 1978 ice breakup at the Yukon River Bridge, north of Fairbanks, Alaska. The report is being distributed by memorandum to researchers in this field. Research on ice forces on highway bridges is included in the Federal Highway Administration Federally Coordinated Program of Highway Research and Development Project SK "New Bridge Design Concepts." Mr. Craig A. Ballinger is the project manager. ~a7,...LJJ/~ Charles F-: ~£fey Director, Office of Research Federal Highway Administration NOTICE This document is disseminated under the sponsorship of the Department of Transportation in the interest of information exchange. The United States Government assumes no liability for its contents or use thereof. The contents of this report reflect the views of the authors who are responsible for the facts and the accuracy of the data presented herein. I The contents do not necessarily reflect the official views or policy of I the Department of Transportation. This report does not constitute a l standard, specification, or regulation. j I The United States Government does not endorse products or manufacturers. -

King Salmon Lower Yukon River

KINGon SALMON the LOWER YUKON RIVER —Past and Present— SPON S ORED BY Yukon river drainage Fisheries Association Anchorage, Alaska PARTICIPANTS Nick Andrew, Sr., Marshall Francis Charlie, Scammon bay Raymond Waska, emmonak Michael Hunt, Kotlik Paul beans, Mountain Village Evan polty, pilot Station Catherine Moncrieff, YRDFA Alice rearden Mark John Ann riordan Davina Carl Rebecca nayamin, Chevak Text by Ann Riordan and Catherine Moncrieff Translations by Rebecca Nayamin and Alice Rearden Funded by the National Science Foundation DECEMBER 2017 QuyanaT H A N K Y O U ! ...to the Elders who participated in the workshop, sharing their knowledge and language. ...to the Lower Yukon Area communities; Mark John, Alice Rearden, and Ann Riordan; and the National Science Foundation for their support. Contents Introduction. 1 Yup’ik Understandings of King Salmon. 5 Salmon preparation. 7 The order of Salmon runs. 9 Natural Indicators of Salmon Arrival and Abundance . 13 The decline of King Salmon, Traditional beliefs and practices . 15 Do not Make noise over Fish. 15 Always Take Animals that present Themselves . 16 Always dispose of Fish Waste on the Land . 16 Negative Impacts of off-shore Fishing. 16 Impacts of beavers. 17 Nets Killing Fish . 17 Negative effects of Fish Hatcheries . 18 Dangerous debris. 18 Climate Change . 18 Problems in Fisheries Management . 19 Conclusions. 22 Salmon Glossary. 25 Lower Yukon River Area Lower Yukon River Area with places identified by Elders during 2017 king salmon workshop. King Salmon on the Lower yukon: past and present 1 Introduction February 1 and 2. Participants were nominated by the tribal councils of the lower Yukon and coastal areas, knowledgeable Elders, and CEC cultural direc- In February 2017, six Yup’ik Elders from Yukon River tor Mark John. -

The Dalton Highway

Te DaDallHtt ooi g nnh w a y Visitor Guide Road Conditions . pages 6-7 Points of Interest . .page 8 Bear Safety . .page 16 Contents Ultimate Road Adventure Trip Planning The Dalton Highway is a rough, industrial road that begins 84 miles/134 km north of Fairbanks and ends 414 miles/662 km later in 4 Preparing and Safety Deadhorse, the industrial camp at Prudhoe Bay. It provides a rare 6 Mileage Chart opportunity to traverse a remote, unpopulated part of Alaska to the 11-14 Maps very top of the continent. Traveling this farthest-north road involves real risks and challenges. This publication will help you decide 23 Planning Your Trip whether to make the journey, how to prepare, and how to enjoy your experience. Please read this information carefully. Exploring Know Before You Go 8-11 Points of Interest • There is no public access to the Arctic Ocean from Deadhorse. 15 An Icebound Land You must be on an authorized tour. Call toll-free 1-877-474-3565; 17 Watching Wildlife in Fairbanks, 474-3565. 18 Recreation • There are no medical facilities between Fairbanks and Deadhorse, a distance of 500 miles/800 km. For emergency information, see the back page. Facilities and Services • Food, gas, and vehicle repair service are extremely limited. 5 Visitor Centers See page 5. 18 Campgrounds • There is limited cell phone service and public Internet connection between Fairbanks and Deadhorse. The Dalton Highway BLM Coordinator: Kelly Egger Contributors: Eugene Ervine, Lenore Heppler, Lisa Shon Jodwalis, Craig McCaa, Pam Rice. John Rapphahn, Crystal Glassburn, Jason Oles, Jason Post Produced and Designed by All photos courtesy of the BLM unless otherwise noted. -

34 Ii.—Physical Characteristics of Canada

34 II.—PHYSICAL CHARACTERISTICS OF CANADA. GEOGRAPHICAL FEATURES. General Formation.—On the eastern coast of the North American continent the Appalachian range of mountains gives shape to the eastern coast of the United States and, extending into Canada, forms the Gaspe peninsula and the Maritime provinces. Around Hudson Bay is a V-shaped plateau constituting the Laurentian highland and extending from Labrador down to the St. Lawrence river and thence northwest ward to the Arctic ocean. In the west are the Cordillera ranges of the Pacific coast, extending into British Columbia and the Yukon territory. They occupy a large area in Canada, and comprise several parallel ranges. In British Columbia they are over 400 miles in width, and consist of the Coast range along the coast; the Rocky mountains, properly so called, and, between them, the Selkirk, Gold, Cariboo, Cassiar and other ranges. To the north of British Columbia lies the Yukon territory, including a great mountain area drained by the Yukon river and the Klondike valley, famous for its gold. West of the Canadian Yukon lies the United States territory of Alaska. Canada may further be conveniently divided into five sections: (1) the penin sula which in Canada includes the Gaspe and the three Maritime provinces: (2) the lowlands of southern Ontario and southern Quebec, with the Great Lakes and the Ottawa and St. Lawrence rivers draining the interior into the Atlantic ocean; (3) the Central plain; (4) the Laurentian highland; (5) the western Cordillera. Mountains.—In the western Cordillera are found the highest mountain ranges and peaks of Canada.