Hidden Treasures of the Tehachapi Region the Found Landscape: A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Palm Haven Garden Plant List - 2010

PALM HAVEN GARDEN PLANT LIST - 2010 BOTANICAL NAME COMMON NAME Achillea millefolium 'Paprika' Paprika yarrow Arctostaphylos glauca big berry manzanita Arctostaphylos pajaroensis Pajaro manzanita Arctostaphylos uva-ursi bearberry Arctostaphylos uva-ursi 'San Bruno Mountain' San Bruno Mountain bearberry Aristolochia californica California pipevine Artemisia pycnocephala coastal sagewort Baccharis pilularis 'Twin Peaks' Twin Peaks dwarf coyote brush Berberis aquifolium 'Golden Abundance' Golden Abundance Oregon-grape Carex spissa San Diego sedge Ceanothus 'Joyce Coulter' Joyce Coulte wild lilac Ceanothus arboreus feltleaf ceanothus Ceanothus gloriosus var exaltatus 'Emily Brown' Emily Brown glory brush Dendromecon harfordii Channel Island tree poppy Epilobium canum California fuchsia Erigeron glaucus seaside daisy Eriogonum fasciculatum California buckwheat Eriogonum latifolium coast buckwheat Eriogonum umbellatum sulfur flower Eriophyllum confertiflorum golden yarrow Heteromeles arbutifolia toyon Heterotheca sessilifolora false goldenaster Iris douglasiana Douglas iris Leymus condensatus 'Canyon Prince' Canyon Prince giant wild rye Mimulus aurantiacus sticky monkeyflower Monardella villosa coyote mint Mulhenbergia rigens deer grass Penstemon heterophyllus foothill penstemon Physocarpus capitatus ninebark Rhamnus californica 'Ed Holm' Ed Holm coffeeberry Rhamnus californica 'Mound San Bruno' Mound San Bruno coffeeberry Salvia clevelandii Cleveland sage Salvia mellifera 'Shirley's Creeper' Shirley's Creepe sage Salvia sonomensis 'Bee's Bliss' Bee's Bliss sage Satureja douglasii yerba buena Trichostema lanatum wolly blue curls Typha angustifolia narrow-leaved cattail Verbena lilacina lilac verbena Vitis californica 'Roger's Red' Roger's Red California wild grape. -

Summary of Offerings in the PBS Bulb Exchange, Dec 2012- Nov 2019

Summary of offerings in the PBS Bulb Exchange, Dec 2012- Nov 2019 3841 Number of items in BX 301 thru BX 463 1815 Number of unique text strings used as taxa 990 Taxa offered as bulbs 1056 Taxa offered as seeds 308 Number of genera This does not include the SXs. Top 20 Most Oft Listed: BULBS Times listed SEEDS Times listed Oxalis obtusa 53 Zephyranthes primulina 20 Oxalis flava 36 Rhodophiala bifida 14 Oxalis hirta 25 Habranthus tubispathus 13 Oxalis bowiei 22 Moraea villosa 13 Ferraria crispa 20 Veltheimia bracteata 13 Oxalis sp. 20 Clivia miniata 12 Oxalis purpurea 18 Zephyranthes drummondii 12 Lachenalia mutabilis 17 Zephyranthes reginae 11 Moraea sp. 17 Amaryllis belladonna 10 Amaryllis belladonna 14 Calochortus venustus 10 Oxalis luteola 14 Zephyranthes fosteri 10 Albuca sp. 13 Calochortus luteus 9 Moraea villosa 13 Crinum bulbispermum 9 Oxalis caprina 13 Habranthus robustus 9 Oxalis imbricata 12 Haemanthus albiflos 9 Oxalis namaquana 12 Nerine bowdenii 9 Oxalis engleriana 11 Cyclamen graecum 8 Oxalis melanosticta 'Ken Aslet'11 Fritillaria affinis 8 Moraea ciliata 10 Habranthus brachyandrus 8 Oxalis commutata 10 Zephyranthes 'Pink Beauty' 8 Summary of offerings in the PBS Bulb Exchange, Dec 2012- Nov 2019 Most taxa specify to species level. 34 taxa were listed as Genus sp. for bulbs 23 taxa were listed as Genus sp. for seeds 141 taxa were listed with quoted 'Variety' Top 20 Most often listed Genera BULBS SEEDS Genus N items BXs Genus N items BXs Oxalis 450 64 Zephyranthes 202 35 Lachenalia 125 47 Calochortus 94 15 Moraea 99 31 Moraea -

Petition to List Mountain Lion As Threatened Or Endangered Species

BEFORE THE CALIFORNIA FISH AND GAME COMMISSION A Petition to List the Southern California/Central Coast Evolutionarily Significant Unit (ESU) of Mountain Lions as Threatened under the California Endangered Species Act (CESA) A Mountain Lion in the Verdugo Mountains with Glendale and Los Angeles in the background. Photo: NPS Center for Biological Diversity and the Mountain Lion Foundation June 25, 2019 Notice of Petition For action pursuant to Section 670.1, Title 14, California Code of Regulations (CCR) and Division 3, Chapter 1.5, Article 2 of the California Fish and Game Code (Sections 2070 et seq.) relating to listing and delisting endangered and threatened species of plants and animals. I. SPECIES BEING PETITIONED: Species Name: Mountain Lion (Puma concolor). Southern California/Central Coast Evolutionarily Significant Unit (ESU) II. RECOMMENDED ACTION: Listing as Threatened or Endangered The Center for Biological Diversity and the Mountain Lion Foundation submit this petition to list mountain lions (Puma concolor) in Southern and Central California as Threatened or Endangered pursuant to the California Endangered Species Act (California Fish and Game Code §§ 2050 et seq., “CESA”). This petition demonstrates that Southern and Central California mountain lions are eligible for and warrant listing under CESA based on the factors specified in the statute and implementing regulations. Specifically, petitioners request listing as Threatened an Evolutionarily Significant Unit (ESU) comprised of the following recognized mountain lion subpopulations: -

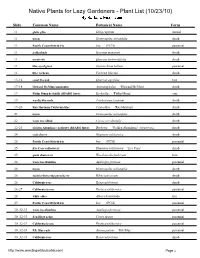

Native Plants for Lazy Gardeners - Plant List (10/23/10)

Native Plants for Lazy Gardeners - Plant List (10/23/10) Slide Common Name Botanical Name Form 11 globe gilia Gilia capitata annual 11 toyon Heteromeles arbutifolia shrub 11 Pacific Coast Hybrid iris Iris (PCH) perennial 11 goldenbush Isocoma menziesii shrub 11 scrub oak Quercus berberidifolia shrub 11 blue-eyed grass Sisyrinchium bellum perennial 11 lilac verbena Verbena lilacina shrub 13-16 coast live oak Quercus agrifolia tree 17-18 Howard McMinn man anita Arctostaphylos 'Howard McMinn' shrub 19 Philip Mun keckiella (RSABG Intro) Keckiella 'Philip Munz' ine 19 woolly bluecurls Trichostema lanatum shrub 19-20 Ray Hartman California lilac Ceanothus 'Ray Hartman' shrub 21 toyon Heteromeles arbutifolia shrub 22 western redbud Cercis occidentalis shrub 22-23 Golden Abundance barberry (RSABG Intro) Berberis 'Golden Abundance' (MAHONIA) shrub 2, coffeeberry Rhamnus californica shrub 25 Pacific Coast Hybrid iris Iris (PCH) perennial 25 Eve Case coffeeberry Rhamnus californica '. e Case' shrub 25 giant chain fern Woodwardia fimbriata fern 26 western columbine Aquilegia formosa perennial 26 toyon Heteromeles arbutifolia shrub 26 fuchsia-flowering gooseberry Ribes speciosum shrub 26 California rose Rosa californica shrub 26-27 California fescue Festuca californica perennial 28 white alder Alnus rhombifolia tree 29 Pacific Coast Hybrid iris Iris (PCH) perennial 30 032-33 western columbine Aquilegia formosa perennial 30 032-33 San Diego sedge Carex spissa perennial 30 032-33 California fescue Festuca californica perennial 30 032-33 Elk Blue rush Juncus patens '.l1 2lue' perennial 30 032-33 California rose Rosa californica shrub http://www weedingwildsuburbia com/ Page 1 30 032-3, toyon Heteromeles arbutifolia shrub 30 032-3, fuchsia-flowering gooseberry Ribes speciosum shrub 30 032-3, Claremont pink-flowering currant (RSA Intro) Ribes sanguineum ar. -

Biological Resources Assessment

APPENDIX B: BIOLOGICAL RESOURCES ASSESSMENT BIOLOGICAL RESOURCES ASSESSMENT Sierra West Assisted Living and Memory Care Project City of Santa Clarita APNs 2827-005-042 & -043 Prepared for: MR. NORRIS WHITMORE P.O. Box 55786 Valencia, CA 91385 Attn: Mr. Norris Whitmore (661) 406-0961 Prepared by: ENVICOM CORPORATION 4165 E. Thousand Oaks Boulevard, Suite 290 WestlaKe Village, CA 91362 Contact: Jim Anderson, Senior Biologist (818) 879-4700 ext. 234 January 2020 Revised February 2020 TABLE OF CONTENTS SECTION PAGE 1.0 INTRODUCTION 1 2.0 METHODS 1 2.1 Biological Resources Inventory 1 2.1.1 Literature Review 1 2.1.2 Field Survey 4 3.0 ENVIRONMENTAL SETTING 4 4.0 BIOLOGICAL RESOURCES 6 4.1 Vegetation and Plant Communities 6 4.1.1 Vegetation 6 4.1.2 Natural Communities of Special Concern 8 4.1.3 Plant Communities/Habitats Listed in CNDDB 9 4.2 Plant Species 10 4.2.1 Plant Species Observed 10 4.2.2 Special-Status Plant Species 10 4.3 Wildlife Species 12 4.3.1 Wildlife Observed 12 4.3.2 Special-Status Wildlife Species 12 4.4 Wildlife Movement 15 5.0 PROJECT IMPACTS 16 5.1 Impacts to Special-Status Plants 18 5.2 Impacts to Special-Status Wildlife 19 5.3 Impacts to Nesting Birds 20 6.0 REFERENCES 22 FIGURES Figure 1 Location Map 2 Figure 2 Aerial Image of the Project Site/Photo Location Map 3 Figure 3 Vegetation and Impacts Map 7 PLATE Plate 1 Representative Photographs of the Project Site and Habitats 5 Biological Resources Assessment S ierra West Assisted Living and Memory Care Project City of Santa Clarita i TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLES Table 1 Natural -

Likely to Have Habitat Within Iras That ALLOW Road

Item 3a - Sensitive Species National Master List By Region and Species Group Not likely to have habitat within IRAs Not likely to have Federal Likely to have habitat that DO NOT ALLOW habitat within IRAs Candidate within IRAs that DO Likely to have habitat road (re)construction that ALLOW road Forest Service Species Under NOT ALLOW road within IRAs that ALLOW but could be (re)construction but Species Scientific Name Common Name Species Group Region ESA (re)construction? road (re)construction? affected? could be affected? Bufo boreas boreas Boreal Western Toad Amphibian 1 No Yes Yes No No Plethodon vandykei idahoensis Coeur D'Alene Salamander Amphibian 1 No Yes Yes No No Rana pipiens Northern Leopard Frog Amphibian 1 No Yes Yes No No Accipiter gentilis Northern Goshawk Bird 1 No Yes Yes No No Ammodramus bairdii Baird's Sparrow Bird 1 No No Yes No No Anthus spragueii Sprague's Pipit Bird 1 No No Yes No No Centrocercus urophasianus Sage Grouse Bird 1 No Yes Yes No No Cygnus buccinator Trumpeter Swan Bird 1 No Yes Yes No No Falco peregrinus anatum American Peregrine Falcon Bird 1 No Yes Yes No No Gavia immer Common Loon Bird 1 No Yes Yes No No Histrionicus histrionicus Harlequin Duck Bird 1 No Yes Yes No No Lanius ludovicianus Loggerhead Shrike Bird 1 No Yes Yes No No Oreortyx pictus Mountain Quail Bird 1 No Yes Yes No No Otus flammeolus Flammulated Owl Bird 1 No Yes Yes No No Picoides albolarvatus White-Headed Woodpecker Bird 1 No Yes Yes No No Picoides arcticus Black-Backed Woodpecker Bird 1 No Yes Yes No No Speotyto cunicularia Burrowing -

Mammals of the California Desert

MAMMALS OF THE CALIFORNIA DESERT William F. Laudenslayer, Jr. Karen Boyer Buckingham Theodore A. Rado INTRODUCTION I ,+! The desert lands of southern California (Figure 1) support a rich variety of wildlife, of which mammals comprise an important element. Of the 19 living orders of mammals known in the world i- *- loday, nine are represented in the California desert15. Ninety-seven mammal species are known to t ':i he in this area. The southwestern United States has a larger number of mammal subspecies than my other continental area of comparable size (Hall 1981). This high degree of subspeciation, which f I;, ; leads to the development of new species, seems to be due to the great variation in topography, , , elevation, temperature, soils, and isolation caused by natural barriers. The order Rodentia may be k., 2:' , considered the most successful of the mammalian taxa in the desert; it is represented by 48 species Lc - occupying a wide variety of habitats. Bats comprise the second largest contingent of species. Of the 97 mammal species, 48 are found throughout the desert; the remaining 49 occur peripherally, with many restricted to the bordering mountain ranges or the Colorado River Valley. Four of the 97 I ?$ are non-native, having been introduced into the California desert. These are the Virginia opossum, ' >% Rocky Mountain mule deer, horse, and burro. Table 1 lists the desert mammals and their range 1 ;>?-axurrence as well as their current status of endangerment as determined by the U.S. fish and $' Wildlife Service (USWS 1989, 1990) and the California Department of Fish and Game (Calif. -

Jeremy Langley Chief Operations Officer Wilhite Langley, Inc. 21800 Barton Road, Ste 102 Grand Terrace, Ca 92313

47 1st Street, Suite 1 Redlands, CA 92373-4601 (909) 915-5900 May 22, 2019 Jeremy Langley Chief Operations Officer Wilhite Langley, Inc. 21800 Barton Road, Ste 102 Grand Terrace, Ca 92313 RE: Biological Resources Assessment, Jurisdictional Waters Delineation Glen Helen/Devore parcel - APN: 0261-161-17, Devore, CA Dear Mr. Langley: Jericho Systems, Inc. (Jericho) is pleased to provide this letter report that details the results of a general Biological Resources Assessment (BRA) that includes habitat suitability assessments for nesting birds, Burrowing owl (Athene cunicularia) [BUOW] and a Jurisdictional Waters Delineation (JD) for the proposed Glen Helen/Devore parcel (Project) located within Assessor’s Parcel Number (APN) #0261-161-17 in the community of Devore, CA (Attachment B: Figures 1 and 2). This report is designed to address potential effects of the proposed Project to designated Critical Habitats and/or any species currently listed or formally proposed for listing as endangered or threatened under the federal Endangered Species Act (ESA) and the California Endangered Species Act (CESA), or species designated as sensitive by the California Department of Fish and Wildlife (CDFW), or the California Native Plant Society (CNPS). Attention was focused on sensitive species known to occur locally. This report also addresses resources protected under the Migratory Bird Treaty Act, federal Clean Water Act (CWA) regulated by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (USACE) and Regional Water Quality Control Board (RWQCB) respectively; and Section 1602 of the California Fish and Game Code (FCG) administered by the CDFW. SITE LOCATION The approximately 1-acre parcel (APN: 0261-161-17) is located north of Kendall Drive just north of the intersection with N. -

IP Athos Renewable Energy Project, Plan of Development, Appendix D.2

APPENDIX D.2 Plant Survey Memorandum Athos Memo Report To: Aspen Environmental Group From: Lehong Chow, Ironwood Consulting, Inc. Date: April 3, 2019 Re: Athos Supplemental Spring 2019 Botanical Surveys This memo report presents the methods and results for supplemental botanical surveys conducted for the Athos Solar Energy Project in March 2019 and supplements the Biological Resources Technical Report (BRTR; Ironwood 2019) which reported on field surveys conducted in 2018. BACKGROUND Botanical surveys were previously conducted in the spring and fall of 2018 for the entirety of the project site for the Athos Solar Energy Project (Athos). However, due to insufficient rain, many plant species did not germinate for proper identification during 2018 spring surveys. Fall surveys in 2018 were conducted only on a reconnaissance-level due to low levels of rain. Regional winter rainfall from the two nearest weather stations showed rainfall averaging at 0.1 inches during botanical surveys conducted in 2018 (Ironwood, 2019). In addition, gen-tie alignments have changed slightly and alternatives, access roads and spur roads have been added. PURPOSE The purpose of this survey was to survey all new additions and re-survey areas of interest including public lands (limited to portions of the gen-tie segments), parcels supporting native vegetation and habitat, and windblown sandy areas where sensitive plant species may occur. The private land parcels in current or former agricultural use were not surveyed (parcel groups A, B, C, E, and part of G). METHODS Survey Areas: The area surveyed for biological resources included the entirety of gen-tie routes (including alternates), spur roads, access roads on public land, parcels supporting native vegetation (parcel groups D and F), and areas covered by windblown sand where sensitive species may occur (portion of parcel group G). -

Idell Weydemeyer's Native Plants TREES SHRUBS & SUBSHRUBS

Idell Weydemeyer’s Native Plants 11-04 Note: • All plants on here are drought resistant except those originating in moist areas. Some will die if given summer water. Sun required unless shade is mentioned. • “LOCAL” means found growing in Idell’s garden or within 100 yards; “Local” means growing within ten miles from the garden. • Thr & Endgr refers to plant posting on Threatened or Endangered List. • There is disagreement among authors as to the range or locations for various plants. TREES Native Plant Common Name Location Aesculus californica California Buckeye LOCAL; Central Coast Ranges to Sierras & Tehachapis; in woodlands, forests & chaparral; on dry slopes & canyons near water; takes clay; deciduous by July or August Arbutus menziesii Madrone Coast Ranges from Baja to British Columbia & N. Sierras; wooded slopes & canyons; full sun to high afternoon shade, well drained acidic soil Calocedrus decurrens Incense Cedar Oregon to Baja, Nevada & Utah; sandy to clay soil Cercidium floridum Palo Verde California, Arizona, Mexico & Central America; Southern California desert in creosote bush Blue Palo Verde scrub & Colorado Desert (in CA) below 3,000 feet; by dry creeks with water in summer & winter, perfect drainage, no summer water; deciduous part of year Pinus (possibly jeffreyi) Jeffrey Pine Platanus racemosa California Sycamore Coast Ranges & foothills in warmer parts of CA; along creeks; drought tolerant only with high Western Sycamore water table or along coast, tolerates full sun, part shade, seasonal flooding, sand & clay soil; deciduous in fall & winter Populus Cottonwood Regular water; deciduous in winter Prunus ilicifolia Holly-leaved Cherry Coast Ranges from Napa southward into Mexico & to Santa Catalina & San Clement Islands; on dry slopes & flats of foothills Prunus subcordata Klamath Plum Southern California Sierras, Northern California into Oregon; some moisture; deciduous in Sierra Plum winter Prunus virginiana (probably demissa) Chokecherry Most of the West into S. -

Sierra Nevada Framework FEIS Chapter 3

table of contrents Sierra Nevada Forest Plan Amendment – Part 4.6 4.6. Vascular Plants, Bryophytes, and Fungi4.6. Fungi Introduction Part 3.1 of this chapter describes landscape-scale vegetation patterns. Part 3.2 describes the vegetative structure, function, and composition of old forest ecosystems, while Part 3.3 describes hardwood ecosystems and Part 3.4 describes aquatic, riparian, and meadow ecosystems. This part focuses on botanical diversity in the Sierra Nevada, beginning with an overview of botanical resources and then presenting a more detailed analysis of the rarest elements of the flora, the threatened, endangered, and sensitive (TES) plants. The bryophytes (mosses and liverworts), lichens, and fungi of the Sierra have been little studied in comparison to the vascular flora. In the Pacific Northwest, studies of these groups have received increased attention due to the President’s Northwest Forest Plan. New and valuable scientific data is being revealed, some of which may apply to species in the Sierra Nevada. This section presents an overview of the vascular plant flora, followed by summaries of what is generally known about bryophytes, lichens, and fungi in the Sierra Nevada. Environmental Consequences of the alternatives are only analyzed for the Threatened, Endangered, and Sensitive plants, which include vascular plants, several bryophytes, and one species of lichen. 4.6.1. Vascular plants4.6.1. plants The diversity of topography, geology, and elevation in the Sierra Nevada combine to create a remarkably diverse flora (see Section 3.1 for an overview of landscape patterns and vegetation dynamics in the Sierra Nevada). More than half of the approximately 5,000 native vascular plant species in California occur in the Sierra Nevada, despite the fact that the range contains less than 20 percent of the state’s land base (Shevock 1996). -

Ventura County Plant Species of Local Concern

Checklist of Ventura County Rare Plants (Twenty-second Edition) CNPS, Rare Plant Program David L. Magney Checklist of Ventura County Rare Plants1 By David L. Magney California Native Plant Society, Rare Plant Program, Locally Rare Project Updated 4 January 2017 Ventura County is located in southern California, USA, along the east edge of the Pacific Ocean. The coastal portion occurs along the south and southwestern quarter of the County. Ventura County is bounded by Santa Barbara County on the west, Kern County on the north, Los Angeles County on the east, and the Pacific Ocean generally on the south (Figure 1, General Location Map of Ventura County). Ventura County extends north to 34.9014ºN latitude at the northwest corner of the County. The County extends westward at Rincon Creek to 119.47991ºW longitude, and eastward to 118.63233ºW longitude at the west end of the San Fernando Valley just north of Chatsworth Reservoir. The mainland portion of the County reaches southward to 34.04567ºN latitude between Solromar and Sequit Point west of Malibu. When including Anacapa and San Nicolas Islands, the southernmost extent of the County occurs at 33.21ºN latitude and the westernmost extent at 119.58ºW longitude, on the south side and west sides of San Nicolas Island, respectively. Ventura County occupies 480,996 hectares [ha] (1,188,562 acres [ac]) or 4,810 square kilometers [sq. km] (1,857 sq. miles [mi]), which includes Anacapa and San Nicolas Islands. The mainland portion of the county is 474,852 ha (1,173,380 ac), or 4,748 sq.